Subscribe or renew today

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

Pelvic exams at hospitals require written consent, new U.S. guidelines say

Hospitals must now get written consent to perform pelvic, breast, prostate and rectal exams on sedated patients or risk losing federal funding.

A new method of making diamonds doesn’t require extreme pressure

A vaccine for bees has an unexpected effect

Glowing octocorals have been around for at least 540 million years

Plant ‘time bombs’ highlight how sneaky invasive species can be

Separating science fact from fiction in Netflix’s ‘3 Body Problem’

A rapid shift in ocean currents could imperil the world’s largest ice shelf

Trending stories.

A new look at Ötzi the Iceman’s DNA reveals new ancestry and other surprises

A new U.S. tool maps where heat will be dangerous for your health

Social media harms teens’ mental health, mounting evidence shows. What now?

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Spotlight on Health

Language models may miss signs of depression in Black people’s Facebook posts

Researchers hope to use social media posts to identify population-wide spikes in depression. That approach could miss Black people, a study shows.

What can period blood reveal about a person’s health?

Immune cells’ intense reaction to the coronavirus may lead to pneumonia, from the archives.

How to Stop a Biological Clock

March 9, 1974 Vol. 105 No. #10

Science News Magazine

April 20, 2024 Vol. 205 No. 8

A new study has linked microplastics to heart attacks and strokes. Here’s what we know

Dogs know words for their favorite toys.

Featured Media

How brain implants are treating depression

This six-part series follows people whose lives have been changed by an experimental treatment called deep brain stimulation.

Explore the expected life spans of different dog breeds

Does this drone image show a newborn white shark? Experts aren’t sure

Parrots can move along thin branches using ‘beakiation’

How ghostly neutrinos could explain the universe’s matter mystery, follow science news.

- Follow Science News on X

- Follow Science News on Facebook

- Follow Science News on Instagram

More Stories

This marine alga is the first known eukaryote to pull nitrogen from air

During a total solar eclipse, some colors really pop. here’s why, this is the first egg-laying amphibian found to feed its babies ‘milk’.

These are the chemicals that give teens pungent body odor

Here’s why covid-19 isn’t seasonal so far, human embryo replicas have gotten more complex. here’s what you need to know.

‘On the Move’ examines how climate change will alter where people live

Waterlogged soils can give hurricanes new life after they arrive on land, cold, dry snaps accompanied three plagues that struck the roman empire.

How a 19th century astronomer can help you watch the total solar eclipse

Jwst spies hints of a neutron star left behind by supernova 1987a, astronomers are puzzled over an enigmatic companion to a pulsar.

Physicists take a major step toward making a nuclear clock

A teeny device can measure subtle shifts in earth’s gravitational field, 50 years ago, superconductors were warming up, health & medicine, aimee grant investigates the needs of autistic people, teens are using an unregulated form of thc. here’s what we know.

Polar forests may have just solved a solar storm mystery

Earth’s oldest known earthquake was probably triggered by plate tectonics, climate change is changing how we keep time, science & society.

In ‘Get the Picture,’ science helps explore the meaning of art

What science news saw during the solar eclipse, your last-minute guide to the 2024 total solar eclipse.

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

Advertisement

Supported by

A Megaraptor Emerges From Footprint Fossils

A series of foot tracks in southeastern China points to the discovery of a giant velociraptor relative, paleontologists suggest in a new study.

By Jack Tamisiea

Could Eating Less Help You Live Longer?

Calorie restriction and intermittent fasting both increase longevity in animals, aging experts say. Here’s what that means for you.

By Dana G. Smith

In Coral Fossils, Searching for the First Glow of Bioluminescence

A new study resets the timing for the emergence of bioluminescence back to millions of years earlier than previously thought.

By Sam Jones

Howie Schwab, ESPN Researcher and Trivia Star, Dies at 63

He stepped out of his behind-the-scenes role in 2004 when he was cast as the ultimate sports know-it-all on the game show “Stump the Schwab.”

By Richard Sandomir

New Study Bolsters Idea of Athletic Differences Between Men and Trans Women

Research financed by the International Olympic Committee introduced new data to the unsettled and fractious debate about bans on transgender athletes.

By Jeré Longman

Why Are Younger Adults Developing This Common Heart Condition?

New research suggests that A-fib may be more prevalent, and more dangerous, in people under 65 than previously thought.

By Dani Blum

How Do We Know What Animals Are Really Feeling?

Animal-welfare science tries to get inside the minds of a huge range of species — in order to help improve their lives.

By Bill Wasik and Monica Murphy

Yellowstone’s Wolves: A Debate Over Their Role in the Park’s Ecosystem

New research questions the long-held theory that reintroduction of such a predator caused a trophic cascade, spawning renewal of vegetation and spurring biodiversity.

By Jim Robbins

Generative A.I. Arrives in the Gene Editing World of CRISPR

Much as ChatGPT generates poetry, a new A.I. system devises blueprints for microscopic mechanisms that can edit your DNA.

By Cade Metz

Scientists Fault Federal Response to Bird Flu Outbreaks on Dairy Farms

Officials have shared little information, saying the outbreak was limited. But asymptomatic cows in North Carolina have changed the assessment.

By Apoorva Mandavilli and Emily Anthes

1 in 5 U.S. Cancer Patients Join in Medical Research

HealthDay April 3, 2024

CDC: Tuberculosis Cases Increasing

While the U.S. has one of the lowest rates of tuberculosis in the world, researchers found that cases increased 16% from 2022 to 2023.

Cecelia Smith-Schoenwalder March 28, 2024

Researchers Find New Way to Curb Asthma Attacks

HealthDay March 26, 2024

Biden to Sign Order Expanding Health Research in Women

HealthDay March 18, 2024

Politics Hasn't Shaken Most Americans' Faith in Science: Study

HealthDay March 12, 2024

Jill Biden Announces $100 Million for Research on Women's Health

HealthDay Feb. 22, 2024

Study Links Living Alone to Depression

New research bound to influence conversations about America’s ‘loneliness epidemic’ suggests living alone could have implications for physical and mental health.

Steven Ross Johnson Feb. 15, 2024

Scientists Discover New Way to Fight Estrogen-Fueled Breast Cancer

HealthDay Feb. 14, 2024

Food Insecurity Tied to Early Death

An inability to get adequate food is shaving years off people’s lives in the U.S., a new study suggests.

Steven Ross Johnson Jan. 29, 2024

Dana Farber Cancer Center to Retract or Fix Dozens of Studies

HealthDay Jan. 23, 2024

America 2024

Climate change damage could cost $38 trillion per year by 2050, study finds

- Medium Text

Sign up here.

Reporting by Riham Alkousaa, Editing by Rachel More, Katy Daigle and Barbara Lewis

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. New Tab , opens new tab

Thomson Reuters

Riham Alkousaa is the energy and climate change correspondent for Reuters in Germany, covering Europe’s biggest economy's green transition and Europe’s energy crisis. Alkousaa is a Columbia University Journalism School graduate and has 10 years of experience as a journalist covering Europe’s refugee crisis and the Syrian civil war for publications such Der Spiegel Magazine, USA Today and the Washington Times. Alkousaa was on two teams that won Reuters Journalist of the year awards in 2022 for her coverage of Europe’s energy crisis and the Ukraine war. She has also won the Foreign Press Association Award in 2017 in New York and the White House Correspondent Association Scholarship that year.

Business Chevron

Oil eases as US demand concerns outweigh fears over Middle East conflicts

Oil prices eased in early trade on Thursday as concerns about a potential slowdown in the U.S. economy amid prospects for delayed interest rate cuts outweighed worries over the risk of expanding conflict in the Middle East.

Singapore's Keppel said on Thursday its first-quarter net profit excluding the effects of legacy offshore and marine assets was higher, boosted by strong performance in the global asset manager's infrastructure and connectivity segments.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- Your Health

- Treatments & Tests

- Health Inc.

- Public Health

How to Thrive as You Age

Got tinnitus a device that tickles the tongue helps this musician find relief.

Allison Aubrey

After using the Lenire device for an hour each day for 12 weeks, Victoria Banks says her tinnitus is "barely noticeable." David Petrelli/Victoria Banks hide caption

After using the Lenire device for an hour each day for 12 weeks, Victoria Banks says her tinnitus is "barely noticeable."

Imagine if every moment is filled with a high-pitched buzz or ring that you can't turn off.

More than 25 million adults in the U.S., have a condition called tinnitus, according to the American Tinnitus Association. It can be stressful, even panic-inducing and difficult to manage. Dozens of factors can contribute to the onset of tinnitus, including hearing loss, exposure to loud noise or a viral illness.

There's no cure, but there are a range of strategies to reduce the symptoms and make it less bothersome, including hearing aids, mindfulness therapy , and one newer option – a device approved by the FDA to treat tinnitus using electrical stimulation of the tongue.

The device has helped Victoria Banks, a singer and songwriter in Nashville, Tenn., who developed tinnitus about three years ago.

"The noise in my head felt like a bunch of cicadas," Banks says. "It was terrifying." The buzz made it difficult for her to sing and listen to music. "It can be absolutely debilitating," she says.

Shots - Health News

Tinnitus bothers millions of americans. here's how to turn down the noise.

Banks tried taking dietary supplements , but those didn't help. She also stepped up exercise, but that didn't bring relief either. Then she read about a device called Lenire, which was approved by the FDA in March 2023. It includes a plastic mouthpiece with stainless steel electrodes that electrically stimulate the tongue. It is the first device of its kind to be approved for tinnitus.

"This had worked for other people, and I thought I'm willing to try anything at this point," Banks recalls.

She sought out audiologist Brian Fligor, who treats severe cases of tinnitus in the Boston area. Fligor was impressed by the results of a clinical trial that found 84% of participants who tried Lenire experienced a significant reduction in symptoms. He became one of the first providers in the U.S. to use the device with his patients. Fligor also served on an advisory panel assembled by the company who developed it.

"A good candidate for this device is somebody who's had tinnitus for at least three months," Fligor says, emphasizing that people should be evaluated first to make sure there's not an underlying medical issue.

Tinnitus often accompanies hearing loss, but Victoria Banks' hearing was fine and she had no other medical issue, so she was a good candidate.

Banks used the device for an hour each day for 12 weeks. During the hour-long sessions, the electrical stimulation "tickles" the tongue, she says. In addition, the device includes a set of headphones that play a series of tones and ocean-wave sounds.

The device works, in part, by shifting the brain's attention away from the buzz. We're wired to focus on important information coming into our brains, Fligor says. Think of it as a spotlight at a show pointed at the most important thing on the stage. "When you have tinnitus and you're frustrated or angry or scared by it, that spotlight gets really strong and focused on the tinnitus," Fligor says.

"It's the combination of what you're feeling through the nerves in your tongue and what you're hearing through your ears happening in synchrony that causes the spotlight in your brain to not be so stuck on the tinnitus," Fligor explains.

A clinical trial found 84% of people who used the device experienced a significant reduction in symptoms. Brian Fligor hide caption

A clinical trial found 84% of people who used the device experienced a significant reduction in symptoms.

"It unsticks your spotlight" and helps desensitize people to the perceived noise that their tinnitus creates, he says.

Banks says the ringing in her ears did not completely disappear, but now it's barely noticeable on most days.

"It's kind of like if I lived near a waterfall and the waterfall was constantly going," she says. Over time, the waterfall sound fades out of consciousness.

"My brain is now focusing on other things," and the buzz is no longer so distracting. She's back to listening to music, writing music, and performing music." I'm doing all of those things," she says.

When the buzz comes back into focus, Banks says a refresher session with the device helps.

A clinical trial found that 84% of people who tried Lenire , saw significant improvements in their condition. To measure changes, the participants took a questionnaire that asked them to rate how much tinnitus was impacting their sleep, sense of control, feelings of well-being and quality of life. After 12 weeks of using the device, participants improved by an average of 14 points.

"Where this device fits into the big picture, is that it's not a cure-all, but it's quickly become my go-to," for people who do not respond to other ways of managing tinnitus, Fligor says.

One down-side is the cost. Banks paid about $4,000 for the Lenire device, and insurance doesn't cover it. She put the expense on her credit card and paid it off gradually.

Fligor hopes that as the evidence of its effectiveness accumulates, insurers will begin to cover it. Despite the cost, more than 80% of participants in the clinical trial said they would recommend the device to a friend with tinnitus.

But, it's unclear how long the benefits last. Clinical trials have only evaluated Lenire over a 1-year period. "How durable are the effects? We don't really know yet," says audiologist Marc Fagelson, the scientific advisory committee chair of the American Tinnitus Association. He says research is promising but there's still more to learn.

Fagelson says the first step he takes with his patients is an evaluation for hearing loss. Research shows that hearing aids can be an effective treatment for tinnitus among people who have both tinnitus and hearing loss, which is much more common among older adults. An estimated one-third of adults 65 years of age and older who have hearing loss, also have tinnitus.

"We do see a lot of patients, even with very mild loss, who benefit from hearing aids," Fagelson says, but in his experience it's about 50-50 in terms of improving tinnitus. Often, he says people with tinnitus need to explore options beyond hearing aids.

Bruce Freeman , a scientist at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, says he's benefitted from both hearing aids and Lenire. He was fitted for the device in Ireland where it was developed, before it was available in the U.S.

Freeman agrees that the ringing never truly disappears, but the device has helped him manage the condition. He describes the sounds that play through the device headphones as very calming and "almost hypnotic" and combined with the tongue vibration, it's helped desensitize him to the ring.

Freeman – who is a research scientist – says he's impressed with the results of research, including a study published in Nature, Scientific Reports that points to significant improvements among clinical trial participants with tinnitus.

Freeman experienced a return of his symptoms when he stopped using the device. "Without it the tinnitus got worse," he says. Then, when he resumed use, it improved.

Freeman believes his long-term exposure to noisy instruments in his research laboratory may have played a role in his condition, and also a neck injury from a bicycle accident that fractured his vertebra. "All of those things converged," he says.

Freeman has developed several habits that help keep the high-pitched ring out of his consciousness and maintain good health. "One thing that does wonders is swimming," he says, pointing to the swooshing sound of water in his ears. "That's a form of mindfulness," he explains.

When it comes to the ring of tinnitus, "it comes and goes," Freeman says. For now, it has subsided into the background, he told me with a sense of relief. "The last two years have been great," he says – a combination of the device, hearing aids and the mindfulness that comes from a swim.

This story was edited by Jane Greenhalgh

- ringing in ears

- hearing loss

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 28 September 2021

News media coverage of COVID-19 public health and policy information

- Katharine J. Mach 1 , 2 ,

- Raúl Salas Reyes ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1683-8516 3 ,

- Brian Pentz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2713-6699 3 ,

- Jennifer Taylor ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8301-3434 4 ,

- Clarissa A. Costa 3 ,

- Sandip G. Cruz 3 ,

- Kerronia E. Thomas 3 ,

- James C. Arnott ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3989-6724 5 ,

- Rosalind Donald 1 ,

- Kripa Jagannathan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4584-8358 6 , 7 ,

- Christine J. Kirchhoff ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2686-6764 8 ,

- Laura C. Rosella ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4867-869X 9 &

- Nicole Klenk ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8224-6992 3

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 220 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

38k Accesses

55 Citations

72 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cultural and media studies

- Science, technology and society

During a pandemic, news media play a crucial role in communicating public health and policy information. Traditional newspaper coverage is important amidst increasing disinformation, yet uncertainties make covering health risks and efforts to limit transmission difficult. This study assesses print and online newspaper coverage of the coronavirus disease COVID-19 for March 2020, when the global pandemic was declared, through August 2020 in three countries: Canada (with the lowest per-capita case and death rates during the study timeframe), the United Kingdom (with a pronounced early spike), and the United States (with persistently high rates). Tools previously validated for pandemic-related news records allow measurement of multiple indicators of scientific quality (i.e., reporting that reflects the state of scientific knowledge) and of sensationalism (i.e., strategies rendering news as more extraordinary than it really is). COVID-19 reporting had moderate scientific quality and low sensationalism across 1331 sampled articles in twelve newspapers spanning the political spectrums of the three countries. Newspapers oriented towards the populist-right had the lowest scientific quality in reporting, combined with very low sensationalism in some cases. Against a backdrop of world-leading disease rates, U.S. newspapers on the political left had more exposing coverage, e.g., focused on policy failures or misinformation, and more warning coverage, e.g., focused on the risks of the disease, compared to U.S. newspapers on the political right. Despite the generally assumed benefits of low sensationalism, pandemic-related coverage with low scientific quality that also failed to alert readers to public-health risks, misinformation, or policy failures may have exacerbated the public-health effects of the disease. Such complexities will likely remain central for both pandemic news media reporting and public-health strategies reliant upon it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Newspapers’ coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic in Eswatini: from distanciated re/presentations to socio-health panics

Spread of awareness of COVID-19 between December 2019 and March 2020 in France

Anti-intellectualism and the mass public’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic

Introduction.

News media reporting is understood to play a central role during national security and health emergencies (Laing, 2011 ; Klemm et al., 2016 ; Pieri, 2019 ). News coverage communicates risks to readers and shapes public perceptions through the amount, content, and tone of reporting. It simultaneously frames ongoing public debates about policy responses, including conflicting priorities relevant to the timing or stringency of implemented policies (Laing, 2011 ; Pieri, 2019 ). Pandemic policy-making requires rapid, iterative responses under conditions of knowledge deficit, as well as the coordination of multi-level public-health agencies and sectors (e.g., hospitals, schools, and workplaces) (Laing, 2011 ; Rosella et al., 2013 ). In these complex circumstances, news media serve as a primary source of health information and uncertainties and connect health professionals, policymakers, and the public in critical ways (Laing, 2011 ; Hoffman and Justicz, 2016 ). The quality and balance of scientific coverage, such as through reporting that reflects the state of scientific knowledge and is not overstated, affect trust in science and accountability for decision-making (Laing, 2011 ; Klemm et al., 2016 ; Hoffman and Justicz, 2016 ).

Inadequate scientific quality in news coverage of past pandemics has posed risks and limited capacities to disseminate public-health guidance and coordinate responses (Hoffman and Justicz, 2016 ). Reporting on the state of scientific knowledge during a novel, evolving pandemic is challenging. Low-quality scientific reporting of pandemics may overstate or understate disease risks or the efficacy of protective measures for different individuals or fail to communicate the nature of the evidence. Such reporting may constrain the feasibility or effectiveness of options for policymakers directing government action, miss opportunities to inform individuals making health decisions, and increase the exposure of health professionals to disease. It can both exacerbate disease outcomes and generate unnecessary fear, in combination with other factors shaping perceptions among the public (Laing, 2011 ; Klemm et al., 2016 ; Hoffman and Justicz, 2016 ). For example, news media reporting may have overly emphasized the threat of the 2009 A/H1N1 influenza (H1N1) pandemic with insufficient indication of available protective measures, and in pairing trustworthy information from credible scientists with uninformed opinions, it may have promoted a “false balance” (Laing, 2011 ; Klemm et al., 2016 ; Hoffman and Justicz, 2016 ). Further, news coverage rapidly waned after the initial pandemic declaration even though public-health risks persisted (Klemm et al., 2016 ; Reintjes et al., 2016 ). Similar issues with media reporting occurred during the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak and the 2014 Ebola outbreak (Hoffman and Justicz, 2016 ; Pieri, 2019 ).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, media representations of complex, rapidly evolving epidemiological science shape public understandings of the risks, measures to limit disease spread, and associated political and policy discourses. Traditional newspaper media coverage may have particular importance given simultaneous misinformation and disinformation, social fragmentation, political polarization, and failures of policy coordination, and national newspapers influence how other outlets cover the same subject across media platforms (Ball and Maxmen, 2020 ; Holtz et al., 2020 ; Thorp, 2020 ; Grossman et al., 2020 ). The COVID-19 pandemic creates an opportunity to assess the strengths and limitations of the media’s pandemic coverage and provide insights for future news media coverage. Such assessment also informs the communication strategies of public-health institutions and policymakers towards clear public-health guidance and coordinated responses across health systems (Laing, 2011 ; Hoffman and Justicz, 2016 ; Pieri, 2019 ).

Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States, our countries of focus, differ in how they govern public health, including pandemic responses. In its constitutionally determined role, the Canadian federal government sets healthcare standards and administers funding to support the healthcare system spanning provinces and territories (Government of Canada, 2016 ). Pandemic health-related policies are set and implemented predominantly by provinces with federal guidance from Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada (Adeel et al., 2020 ). The U.K. central government funds healthcare throughout the United Kingdom yet only sets policies for England. Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales each govern their own National Health Service systems. By contrast, the healthcare system in the United States is a complex mixture of public and private health insurance programs. The U.S. federal government generally adopts a leading role during national crises, although during the COVID-19 pandemic states and municipalities have led adoption and implementation of most policy measures to contain the spread of COVID-19 (Adeel et al., 2020 ). Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2019 Global Health Security Index ranked the United States first, United Kingdom second, and Canada fifth among 195 countries for preparedness to manage a serious disease outbreak (Cameron et al., 2019 ).

In this paper, we systematically quantify the amount, scientific quality, and sensationalism of newspaper media coverage of COVID-19 in Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Newspapers studied span the political spectrum of each case-study country (Table 1 ) (Gentzkow and Shapiro, 2010 ; Puglisi and Snyder, 2015 ; Anderson and Coletto, 2017 ; Mitchell et al., 2018 ; Hönnige et al., 2020 ; Jurkowitz et al., 2020 ; Austen, 2020 ). Our analysis begins two weeks prior to COVID-19’s official recognition as a pandemic and follows its development over the subsequent five months (i.e., from 1 March 2020 to 15 August 2020). Given the volume of COVID-19 news media articles published over the timeframe of this study, we created a manageable corpus for analysis by randomly sampling one day of media coverage per week for six consecutive 4-week periods; we then randomly selected five eligible articles from each news outlet on each sampled day for the evaluation of scientific quality and sensationalism. In our evaluation, scientific quality refers to the alignment between reporting and the state of scientific evidence and its uncertainties, and sensationalism is a discursive strategy rendering news as more extraordinary, interesting, or relevant than it really is (Oxman et al., 1993 ; Molek-Kozakowska, 2013 ; Hoffman and Justicz, 2016 ). We apply previously validated survey tools developed to measure scientific quality and sensationalism of pandemic-related health news records in combination with broader methods from policy analyses of pandemic responses (SI Coding Tool) (Oxman et al., 1993 ; Rosella et al., 2013 ; Molek-Kozakowska, 2013 ; Reintjes et al., 2016 ; Hoffman and Justicz, 2016 ). We analyze (1) the COVID-19 public-health outcomes and policies in each country and (2) the amount, scientific quality, sensationalism, and topics of COVID-19 news media coverage across the political spectrum of each country.

Public health contextualization of news media analyses

To contextualize our news media analyses, we analyzed and visualized existing data sets on the number of COVID-19 cases, deaths, and tests in each country (e.g., Roser et al., 2020 ; CBC News, 2020 ; Public Health England and NHSX, 2020 ; CDC, 2020 ). We also recorded the key public-health declarations, policies, and guidance during the study time period (e.g., drawing from WHO, 2020a , 2020b ; see also SI Table S1 ). We tracked these decisions at international scales through to subnational scales in each country studied. Media analyses outlined below thereby were considered with respect to the reported number of cases and confirmed deaths and policy actions taken (Reintjes et al., 2016 ).

News media search strategy and inclusion criteria

Print and online news media records were retrieved from the Factiva database for news outlets across the political spectrum of Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States (see Table 1 ) (Gentzkow and Shapiro, 2010 ; Puglisi and Snyder, 2015 ; Anderson and Coletto, 2017 ; Mitchell et al., 2018 ; Hönnige et al., 2020 ; Jurkowitz et al., 2020 ; Austen, 2020 ). Selected news media outlets have primary news products in print and online media, rather than television broadcasting or social media, and full article entries available in Factiva. Search terms included “coronavirus,” “COVID-19,” “epidemic,” “outbreak,” “pandemic,” or “SARS-CoV-2.” Individual English-language news articles were retrieved for sampled dates between 1 March 2020 and 15 August 2020. This period captures news media coverage prior to the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic and over the subsequent five months.

Individual news records were screened to identify original news reporting (i.e., news reporting and news analysis articles) relevant to our study objectives. First, eligible articles must have a direct focus on the public-health implications of COVID-19 or on attempts to control its spread—in some or all of an article’s text. By excluding articles without this focus, we ensured all articles included in the study could contain scientific information on the public health effects or spread of COVID-19 and associated policies. Second, eligible articles must be focused on the newspaper’s country of publication (e.g., an article reporting on COVID-19 transmission or mitigation efforts in only New Zealand or China, without discussion of implications for the newspaper’s country of publication, would be excluded). We included this eligibility criterion to analyze science–policy interfaces and science–society interactions most proximate to the news outlets, although we acknowledge that articles about other countries may influence perceptions of readers even without direct discussion of implications for them. Third, eligible articles must be original news reporting or analysis, meaning we excluded opinion pieces, editorials, interview transcripts, microblogs, front-page snippets, news roundups, obituaries, advertisements, corrections memos, and letters to the editor; these excluded article types would have required distinct question framings beyond the scope of our codebook. This third criterion, therefore, ensured that coded responses could be compared coherently across articles for the different measures of scientific quality and sensationalism.

Sampling of news media articles

As the evaluation of scientific quality and sensationalism through manual coding is time intensive, and a very large number of COVID-19 news media articles were published during the timeframe of our study, we used a random sample of news media articles for analysis, prioritizing sampling during each week over the course of the study timeframe. The sample design enabled a manageable analysis of newspaper media coverage and potential changes over the timeframe of the study. First, the sample of news media articles was constructed by sampling one day of media coverage per week in consecutive four-week periods. These four days of the week were randomly sampled without replacement (Monday through Saturday only, not including Sunday in the sampling), given cyclic variation in news media coverage (Lacy et al., 2001 ; Riffe et al., 2016 ). The study timeframe was divided into six four-week periods of equal duration from 1 March to 15 August 2020.

Second, for each randomly sampled day, all available news records were retrieved from Factiva for the 12 news outlets (Table 1 ). Randomly selected articles were screened for eligibility, with the goal of identifying 5 eligible articles for each news outlet on each sampled day. In some cases, fewer than 5 eligible articles were published by a given outlet on a sampled day. In these cases, the full set of eligible articles was included in the study.

Analysis of scientific quality and sensationalism of news articles

The coding tool for measuring scientific quality and sensationalism of news article records was adapted from the final tool of Hoffman and Justicz, designed for evaluating pandemic-related health news records (Hoffman and Justicz, 2016 ). Scientific quality, as defined in that study, is “a measure of an article’s reliability and credibility on a given topic” (Hoffman and Justicz, 2016 ). Importantly, scientific quality is linked to the state of scientific understanding and its uncertainties at specific moments in time rather than being an absolute or objective characteristic. The codebook we applied for measuring scientific quality is therefore designed to be flexible and responsive to the inevitable shifts in scientific understanding that occur through time, most especially during a novel disease outbreak and evolving pandemic. Sensationalism, as defined in that study, is “a way of presenting articles to make them seem more interesting or extraordinary than they actually are” (Hoffman and Justicz, 2016 ).

Our coding tool (SI Coding Tool) included six questions for scientific quality (each evaluated on a scale from 1 to 5—5 corresponding to highest quality) and six questions for sensationalism (each evaluated on a scale from 1 to 5—5 corresponding to highest sensationalism). The question categories (SI Coding Tool) for assessing scientific quality were as follows: applicability, opinion versus facts, validity, precision, context, and global assessment (i.e., an overall assessment of the article’s scientific quality based on the five preceding specific measures). For sensationalism, the question categories (SI Coding Tool) included exposing, speculating, generalizing, warning, extolling, and global assessment (i.e., an overall assessment of the degree of sensationalism in the article based on the five preceding specific measures) (Oxman et al., 1993 ; Molek-Kozakowska, 2013 ; Hoffman and Justicz, 2016 ).

In addition, metadata collected for each article included the coder’s identity, the article title, the article’s sample date, the news outlet (including if the article was originally written by another outlet such as the Associated Press), the societal sector (up to 2 selected per article), and public-health measures discussed (SI Coding Tool).

Coder assignments, training, reliability assessment, and analysis

For each sampled day, two independent coders assessed all relevant news media records based on the scientific quality and sensationalism questions and article-attribute metadata. Coders recorded scores for each article through a Google-form version of the codebook (SI Coding Tool).

To ensure consistent application of the coding tool, substantial training and calibration occurred over a six-week period. First, the three coders in coordination with the project leadership team read national and international public-health agency descriptions of the coronavirus disease and associated public-health policies and measures. Second, the coders completed multiple rounds of individual coding of example news articles, followed by group discussions of application of the codebook. The group discussions considered difficult judgments and common versus unusual examples. The goal was to ensure consistent application of the coding tool across question categories and the range of article examples that arose. During the training and calibration phases of coding, we updated the codebook to include examples specific to news records on COVID-19 (SI Coding Tool), and we tracked illustrative examples (news articles and specific quotes) across the scale (1–3–5) for the scientific quality and sensationalism question categories. This process led to development of example answers particularly representative of low versus high scientific quality and low versus high sensationalism under each category of response. Additionally, we developed “decision rules” for the more unusual or challenging categories of examples to ensure consistency across coders, especially where disagreements arose in individually assigned responses.

Interrater reliability was assessed during the training and calibration stage and throughout the duration of the study. Where coders assigned scores for a given question that were 3 or 4 units apart on the 1–5 scale, a reconciliation discussion occurred; the small fraction of question responses in this category following the training stage enabled the coders and project team to continue developing and ensuring shared understanding of coding approaches for unusual or challenging applications. Weighted Cohen’s Kappa, with quadratic weighting, was applied given the high-inference codebook and ordinal data collected via a Likert scale, as previously done for related measures (Cohen, 1960 ; Fleiss and Cohen, 1973 ; Oxman et al., 1993 ; Antoine et al., 2014 ; Hoffman and Justicz, 2016 ; Tran et al., 2020 ). Coded data were analyzed with Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance and post-hoc multi-comparison pairwise tests (kruskal.test and kruskalmc in pgirmess package in R) (Giraudoux et al., 2018 ; R Core Team, 2020 ).

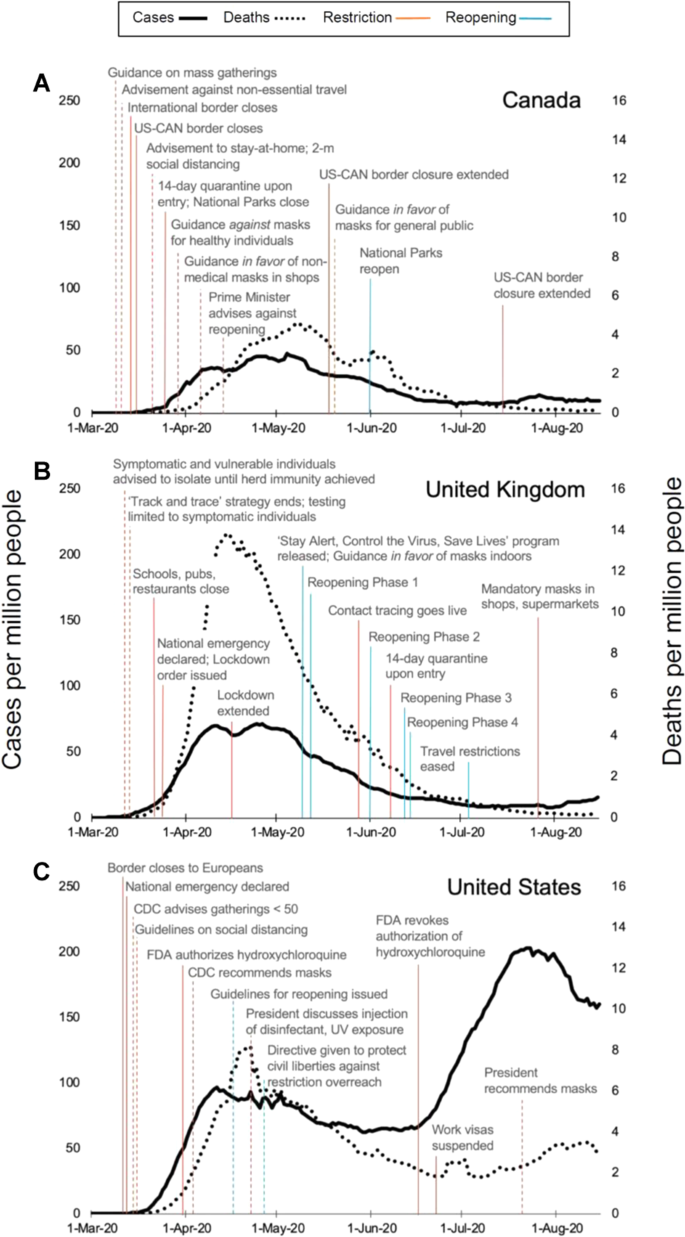

Public health and policy contexts

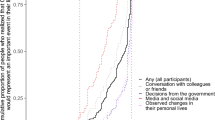

From March through August 2020, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States differed substantially in their public-health responses to COVID-19 and in health outcomes from the novel coronavirus disease (Fig. 1 ). Beginning in early March, all three countries implemented a combination of policy measures to contain the spread of COVID-19, including emergency laws, stay-at-home orders, mask mandates, school and business closures, border and travel restrictions, social distancing measures, and quarantines upon entry (SI Table S1 ). These restrictions were followed by gradual phases of reopening measures allowing restricted social and economic activities to occur. Across the three countries, the role of national versus subnational governments differed with respect to authority and actions on public-health guidance and care, resulting in differing timing and levels of coordination for both restrictions and reopening measures (SI Fig. S1 ). From March to August 2020, the United Kingdom experienced the highest death rate from COVID-19 (maximum 7-day average of 13.9 deaths per million people; Fig. 1 ), whereas the United States had the highest case rate of the three countries (maximum 7-day average of 203.5 cases per million), as well as the greatest cumulative number of cases and deaths globally (SI Figs. S2 - S3 ). Of the three countries, Canada had the most effective public-health outcomes as measured by per capita COVID-19 case or death rates (Fig. 1 ).

COVID-19 cases, deaths, and national-level policies are indicated for ( A ) Canada, ( B ) the United Kingdom, and ( C ) the United States. 7-day rolling averages of cases (left vertical axis, solid black line) and deaths (right vertical axis, dotted black line) per one million people are shown for the timeframe of this media study, 1 March through 15 August 2020 (Roser et al., 2020 ). The timeline for each country specifies national-level public-health policies and guidance, especially emergency declarations, school and non-essential business closures, travel and border restrictions, quarantines and social distancing, mask usage, and reopening phases. Implementation of enforceable policies (solid) and non-enforced guidance (dotted) is specified with vertical red lines, and corresponding reopening and relaxation of policies and guidance are specified with vertical blue lines. Detailed descriptions of national-level policies within each panel are provided in SI Table S1 .

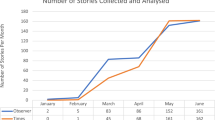

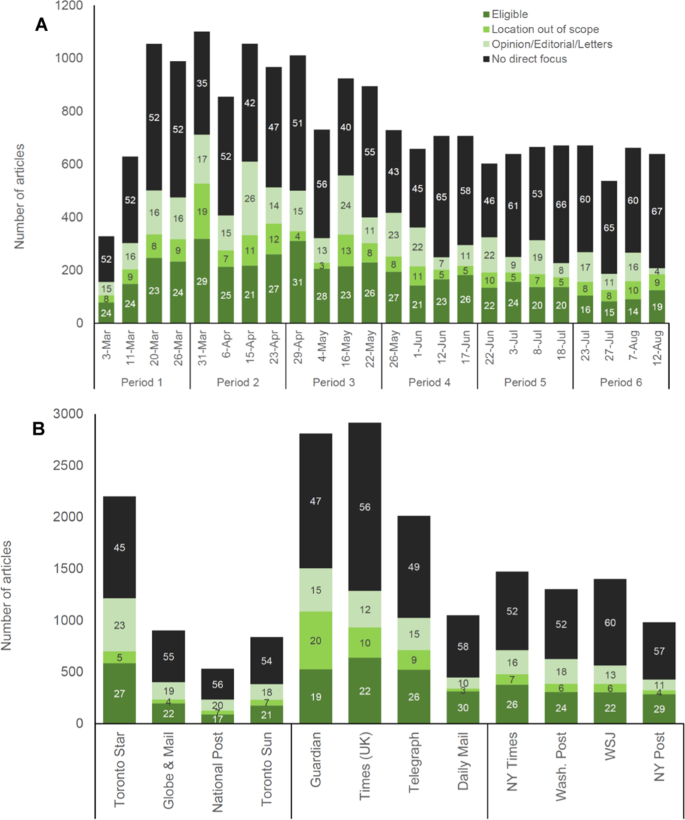

The amount of pandemic media coverage

The studied news outlets differed in the amount of news media coverage related to COVID-19 from 1 March through 15 August 2020 (Fig. 2 ). The amount of coverage increased notably in March as case rates climbed in each country, subsequently decreasing gradually in May and June while case rates also declined. Across the 24 randomly sampled days, the 12 studied news outlets published 18,430 articles related to COVID-19. Of these, an estimated 4321 articles (23.4%) were eligible for inclusion in this study—that is, as news reporting or analysis relevant to the country of publication and containing a direct focus on COVID-19 public health or policy information (SI Figs. S4 - S5 ). Articles with a direct focus on COVID-19 public health or policy information (to a small or large extent) could be coded for the scientific quality of the reporting of this information and its sensationalism.

For each randomly sampled day ( A ) and each news outlet ( B ), the total number of individual news records is shown, based on Factiva database searches for articles related to COVID-19 public health and policy information (Methods). News articles are partitioned across the following categories: articles eligible for inclusion in our study (eligible), articles not focusing on the newspaper’s country of publication (location out of scope), articles that are not original news reporting or analysis (opinion/editorial/letters), and articles that include COVID-19-relevant search terms, but do not include any direct focus on COVID-19 public health or policy information (no direct focus). Estimated totals for these categories are calculated using (i) the total number of Factiva returns and (ii) the rates at which articles were assigned to these categories during the eligibility screening process for each outlet and randomly sampled day (SI Fig. S4 ). On the stacked bars, percentages of articles falling into each category are specified for each day ( A ) and news outlet ( B ).

Content analysis of pandemic media coverage

We collected a manageable, well-defined random sample of 1331 news media articles satisfying our eligibility criteria (SI Fig. S4 ) for coding of scientific quality and sensationalism (SI Coding Tool and Dataset S1 ). Six questions each for scientific quality and for sensationalism were evaluated on a scale from 1 to 5 (5 corresponding to highest scientific quality or sensationalism, 1 corresponding to lowest scientific quality or sensationalism). Question categories included for scientific quality: applicability, opinion versus facts, validity, precision, context, and global assessment (i.e., an overall assessment of the article’s scientific quality); and for sensationalism: exposing, speculating, generalizing, warning, extolling, and global assessment (i.e., an overall assessment of the degree of sensationalism in the article) (SI Coding Tool). For this content analysis, interrater reliability was moderate to substantial for the summative “global” assessment of scientific quality and sensationalism (SI Table S2 ). Reliability was similarly high for specific scientific quality and sensationalism measures, with the exception of questions for which coded scores displayed restriction of range or unbalanced distributions (e.g., “generalizing” scores of mostly 1 and 2, rather than ranging from 1 through 5 with balance around 3; SI Coding Tool and Dataset S1 ) (Hallgren, 2012 ; Tran et al., 2020 ).

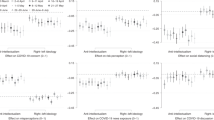

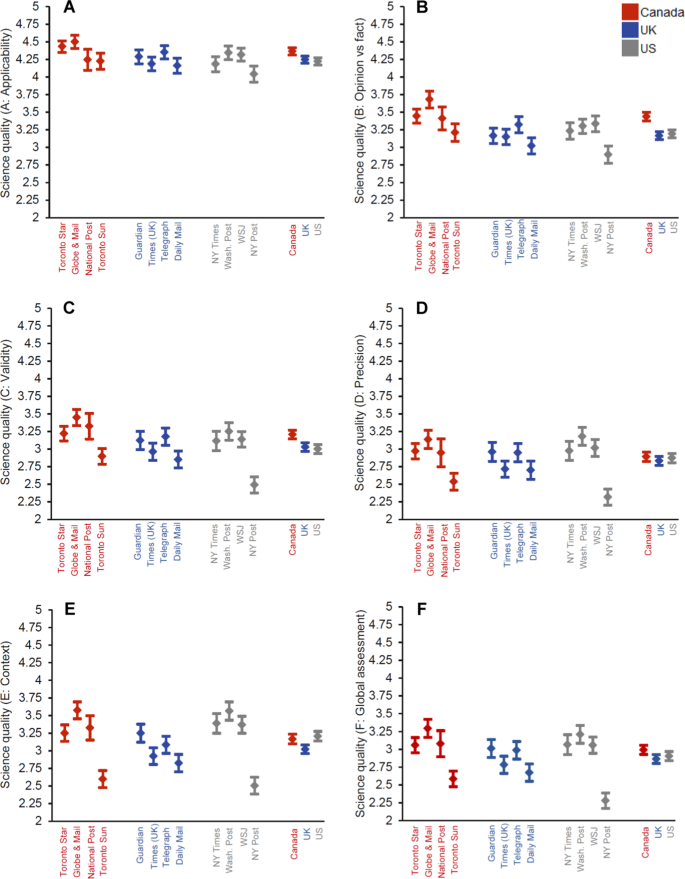

The scientific quality of pandemic media coverage

The scientific quality of news media articles differed among news outlets across the political spectrums of the respective countries (Fig. 3 ). Within each country, the overall scientific quality of news reporting and analysis was lowest on the populist-right of the political spectrum (mean summative “global” scientific quality of 2.58, n = 106 articles, for Toronto Sun ; 2.67, n = 115, for Daily Mail ; and 2.28, n = 118, for New York Post ; p ≤ 0.001 for Kruskal–Wallis, p ≤ 0.05 for within-country pairwise comparisons except Daily Mail versus Times of London and Telegraph , SI Table S3 ). For these outlets, lower scientific quality was especially evident for validity, precision, and context as measures of scientific quality (e.g., articles reporting claims without fact checking, specificity, or background details) (Fig. 3 ).

Scores for six scientific quality questions (SI Coding Tool) are shown (mean, 95% confidence interval) for articles ( n = 1331) communicating COVID-19 public health or policy information (Fig. 2 ): ( A ) applicability, ( B ) opinion versus facts, ( C ) validity, ( D ) precision, ( E ) context, and ( F ) global assessment (i.e., an overall assessment of the article’s scientific quality). Each question was evaluated on a scale from 1 to 5 (5 corresponding to highest scientific quality). Sampled articles were published between 1 March and 15 August 2020 (Methods). Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance and post-hoc multi-comparison test statistics are in SI Table S3 .

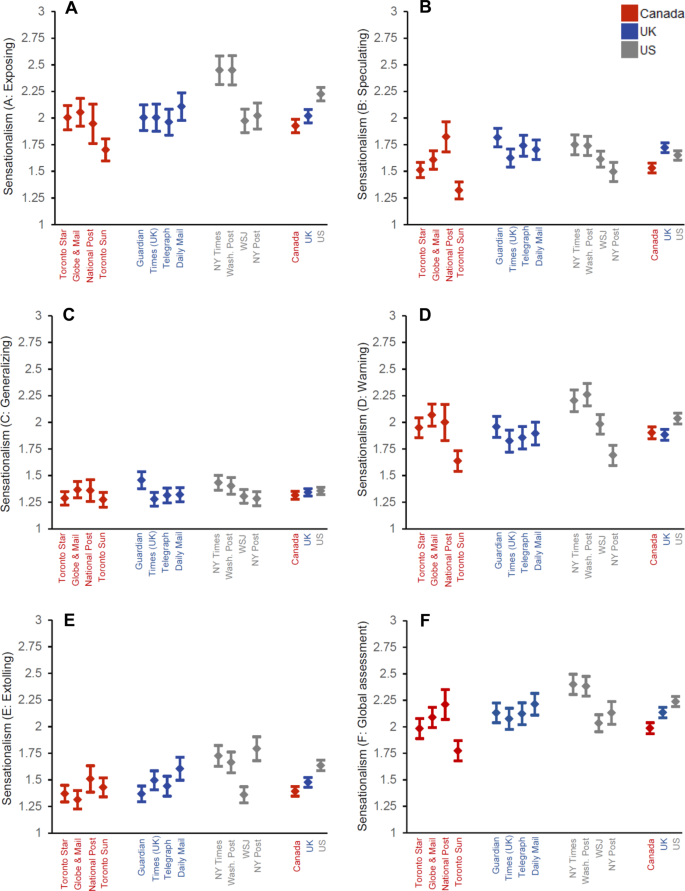

The sensationalism of pandemic media coverage

The sensationalism of news media articles was low overall for all news outlets, although somewhat greater for outlets on the left and middle of the political spectrum in Canada and the United States (Fig. 4F ). In both countries, news outlets at the populist-right combined low scientific quality with low sensationalism (Figs. 3 F and 4F ). In Canada, the overall sensationalism of news reporting and analysis was lowest for the Toronto Sun (mean summative “global” sensationalism of 1.77, n = 106 articles; p ≤ 0.001 for Kruskal–Wallis, p ≤ 0.05 for pairwise comparisons with Globe and Mail and National Post , SI Table S3 ). In the United States, overall sensationalism was lower in the Wall Street Journal (mean global sensationalism of 2.03, n = 118 articles) and New York Post (mean of 2.13, n = 118), as compared to the New York Times (mean of 2.40, n = 120) and Washington Post (mean of 2.38, n = 119; p ≤ 0.001 for Kruskal–Wallis, p ≤ 0.05 for pairwise comparisons, SI Table S3 ). For these outlets, lower sensationalism was especially observed for exposing, speculating, and warning as measures of sensationalism (Fig. 4 ). In the United Kingdom, overall sensationalism did not vary across news outlets ( p = 0.283 for Kruskal–Wallis, SI Table S3 ).

Scores for six sensationalism questions (SI Coding Tool) are shown (mean, 95% confidence interval) for articles ( n = 1331) communicating COVID-19 public health or policy information (Fig. 2 ): ( A ) exposing, ( B ) speculating, ( C ) generalizing, ( D ) warning, ( E ) extolling, and ( F ) global assessment (i.e., an overall assessment of the degree of sensationalism in the article). Each question was evaluated on a scale from 1 to 5 (5 corresponding to highest sensationalism). Sampled articles were published between 1 March and 15 August 2020 (Methods). Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance and post-hoc multi-comparison test statistics are in SI Table S3 .

Syndicated versus original reporting

Across all outlets, the scientific quality of original reporting (mean global scientific quality of 2.93, n = 1278 articles) was significantly higher than the scientific quality of syndicated articles (mean of 2.71, n = 54; p = 0.020, Kruskal–Wallis; SI Fig. S6 and Table S4 ). Additionally, the sensationalism of syndicated articles (mean global sensationalism of 1.82, n = 54 articles) was significantly lower than the sensationalism of original reporting (mean of 2.14, n = 1278; p ≤ 0.001, Kruskal–Wallis; SI Fig. S6 and Table S4 ). The Toronto Sun published the highest proportion of syndicated news articles by far, with 34% of the paper’s 106 coded articles originating from syndicated sources. Other news outlets with more than 1% of coded articles drawing from syndicated sources included the Toronto Star (6% of articles) and the National Post (11%).

Neither scientific quality nor sensationalism varied substantially through time, with the exception of lower scientific quality on 3 July 2020 resulting from limited coverage of the healthcare sector that day (Fig. 5 , SI Fig. S7 ).

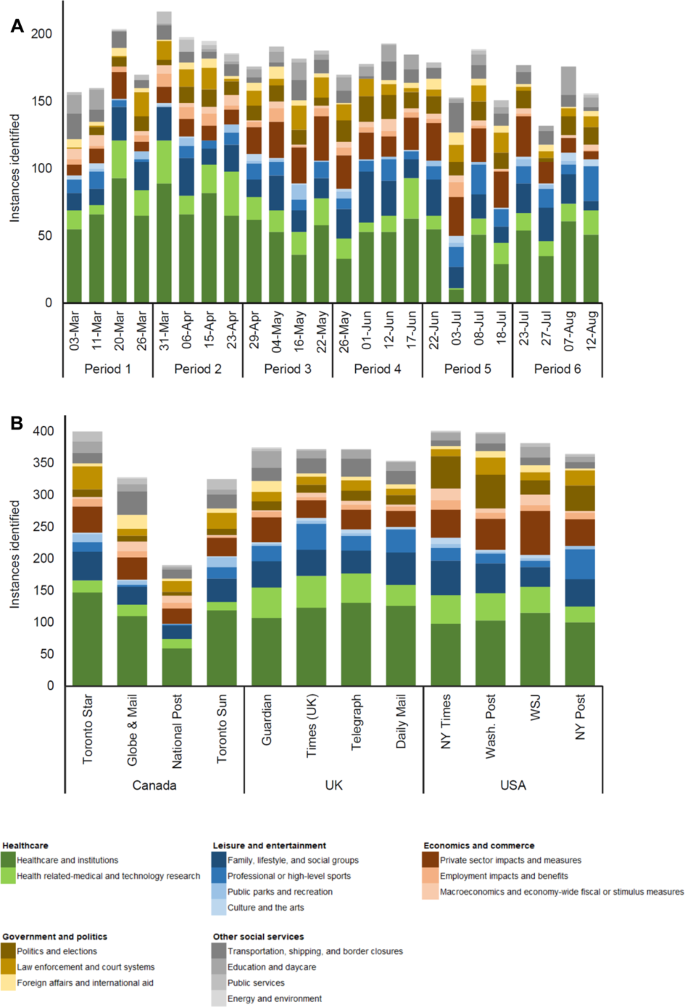

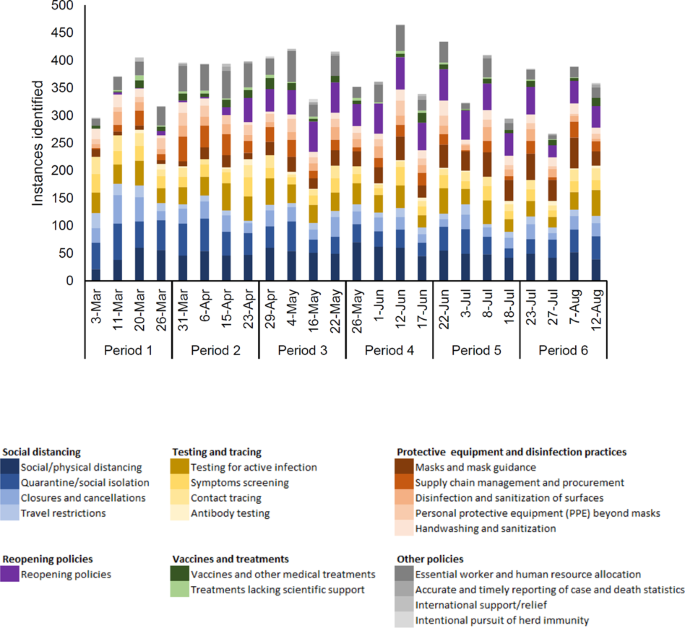

The topics of news media articles analyzed ( A ) over the timeframe of this study and ( B ) by news outlet are specified. Sampled articles were published on randomly sampled days between 1 March and 15 August 2020 (Methods). The topic of each article ( n = 1331) was categorized by societal sectors (up to 2 selected per article) related to healthcare, leisure and entertainment, economics and commerce, government and politics, and other social services.

The topics of pandemic media coverage

News media articles were categorized based on the societal sectors (up to 2 per article) that were the primary focus of each article (Fig. 5 ). The sectors, related to healthcare, leisure and entertainment, economics and commerce, government and politics, and other social services, are listed in full in Figs. 5 and 6 . Although all analyzed articles contained information on the public-health effects of COVID-19 or measures to limit its spread (SI Fig. S4 ), topics of focus differed widely, for example including recreation, the arts, transportation, or daycare, not just medical facilities or vaccine research.

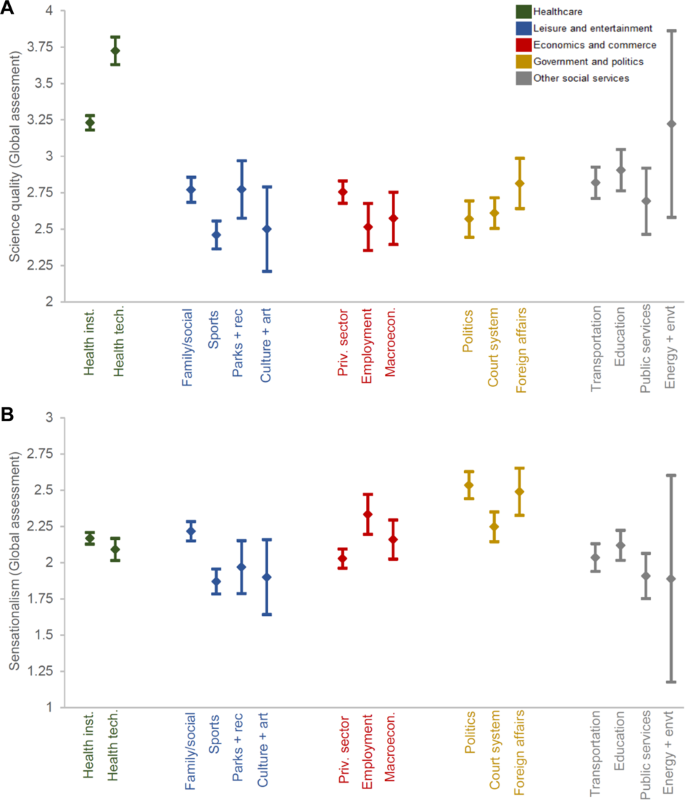

Scientific quality ( A ) and sensationalism ( B ) of news media articles are indicated by the topics of articles. Overall global assessment scores for scientific quality and sensationalism (SI Coding Tool) are shown (mean, 95% confidence interval) for articles communicating COVID-19 public health or policy information (Fig. 2 ). For each article, scientific quality and sensationalism were each evaluated on a scale from 1 to 5 (5 corresponding to highest scientific quality or to highest sensationalism). Sampled articles ( n = 1331) were published between 1 March and 15 August 2020 (Methods). The topic of each article was categorized across the following societal sectors (up to two selected per article): healthcare and institutions; health-related medical and technology research; family, lifestyle, and social groups; professional or high-level sports; public parks and recreation; culture and the arts; private sector impacts and measures; employment impacts and benefits; macroeconomics and economy-wide fiscal or stimulus measures; politics and elections; law enforcement and court systems; foreign affairs and international aid; transportation, shipping, and border closures; education and daycare; public services; and energy and the environment.

The topics of news media articles corresponded to scientific quality and sensationalism of news reporting and analysis to some degree (Fig. 6 ). News media articles related to healthcare, health institutions, and health-related research were most common (Fig. 5 ), and they had significantly greater scientific quality compared to articles on other topics (mean global scientific quality of 3.23 for healthcare and institutions and 3.72 for health-related research; p ≤ 0.001 for Kruskal–Wallis, p ≤ 0.05 for pairwise comparisons except with energy and the environment; Fig. 6A ). News media articles during the first four-week period studied, starting 1 March 2020, included the greatest focus (50.2% of coverage) on healthcare and related institutions and research (Fig. 5A ).

Sensationalism of articles related to politics and foreign affairs was greatest (mean global sensationalism of 2.53 for politics; and of 2.49 for foreign affairs; p < 0.001 for Kruskal–Wallis, p < 0.05 for pairwise comparisons of politics versus all sectors except foreign affairs, employment, and energy and the environment; Fig. 6B ). For example, sensational statements related to politics and foreign affairs could include exposing disinformation from political leaders or extolling political leaders for border closures as a pandemic or broader policy response. News outlets in the United States published the most articles related to politics and elections (63.8% of coverage across all outlets; Fig. 5B ).

Public-health policies consistently covered through time included measures related to social distancing, testing and tracing, and protective equipment and disinfection practices, while coverage of mask guidance and reopening policies increased over the course of the study (Fig. 7 ).

Sampled articles ( n = 1331) were published on randomly sampled days between 1 March and 15 August 2020 (Methods). Public-health policies and measures in each article were coded under specific categories related to social distancing, testing and tracing, protective equipment and disinfection practices, reopening policies, vaccines and treatments, and more (all relevant categories selected for each article).

Managing the public health and societal risks of a pandemic requires iterative, informed decision-making by governments, individuals, and the private sector. News media play a central role in communicating public health and policy information, establishing accountability for decision-making, and shaping public perceptions through the number of news reports, their content, and their tone (Klemm et al., 2016 ; Reintjes et al., 2016 ). For news outlets spanning the political spectrum of three countries with contrasting public-health outcomes and policy responses (Fig. 1 ), based on a random sample of days, coverage related to COVID-19 increased substantially in March 2020 and declined gradually thereafter in May and June (Fig. 2 ), not rebounding even during the dramatic increase in U.S. COVID-19 cases in June and July (SI Figure S5 ). Understanding this news media reporting in the early stages of COVID-19 response provides important lessons for ensuring the accessibility of information in support of public health and gauging its degree of effectiveness in creating accountability for policy decisions.

News media reporting grappled with complications of scientific understanding and its uncertainties during the timeframe of our study, as assessed through our measures of validity, precision, and overall scientific quality. For example, the mechanisms of disease transmission, especially airborne transmission, were slow to be recognized, leading to dynamic adjustments of public-health guidance (e.g., for mask usage by the general public) (Zhang et al., 2020 ). Despite such uncertainties and frequent knowledge updates over time, the scientific quality of reporting was highest for the healthcare sector, also the most commonly occurring article topic (Fig. 6 ). The scientific quality of reporting overall did not improve as the pandemic proceeded and knowledge of COVID-19 increased, which may be attributed to shifts from healthcare to other topics of news media reporting (Fig. 5 and SI Fig. S7 ).

We did, however, identify major differences in the degree to which newspaper reporting of COVID-19 presented high-quality scientific information about the public-health effects of the coronavirus disease and measures to limit its spread. News media articles generally had moderate scientific quality overall (Fig. 3F ). Outlets on the populist-right of the political spectrum of each country, though, had significantly lower scientific quality in reporting related to COVID-19 (Fig. 3F ). Scientific quality was low especially for validity, precision, and context as measures of scientific quality, as well as for the distinction between opinion versus facts in some cases (e.g., articles reporting claims without fact checking, specificity, background details, or sourcing) (Fig. 3 ). These findings pertain to news reporting and analysis, rather than opinion pieces, editorials, or letters, which were excluded from the scope of news media articles we evaluated. The differences across outlets suggest that, in reading news reporting and analysis in different newspapers, readers access reporting of varying scientific quality related to the health risks and effectiveness of available measures to limit disease transmission.

Further, patterns of U.S. media reporting were correlated with failures of national leadership under the Trump Administration, and they may have both reflected and contributed to politicization of COVID-19 in the United States. During this study’s timeframe, the United States led the world in cases and deaths despite its pre-pandemic ranking as the country best equipped to manage a pandemic such as COVID-19 (Cameron et al., 2019 ). These public-health outcomes occurred against a backdrop of disinformation and failures of national leadership (Evanega et al., 2020 ; Ball and Maxmen, 2020 ; Holtz et al., 2020 ; Lincoln, 2020 ; Thorp, 2020 ). Lack of national leadership was observed in the relative dearth of national-level public-health policies and guidance (Fig. 1 ) and the divergence of subnational policy responses, correlated with partisan politics (SI Fig. S1 and Table S1 ). Elites and incumbent governments have outsize influence on public opinion and media coverage, which likely contributed to polarization and politicization of pandemic media coverage (Green et al., 2020 ; Hart et al., 2020 ). Linked to these trends, we observed higher sensationalism related to politics and elections topics and greater coverage of these sectors among U.S. newspapers (Figs. 5 – 6 ). Additionally, news outlets on the political left in the United States (i.e., New York Times , Washington Post ) published articles with more exposing and warning coverage, for example discussing disinformation on the part of government leaders and the risks of disease (Fig. 4 ). Although most Americans believe the media are fulfilling key roles during the pandemic, the majority of these individuals identify as Democrats, and Democrats trust many more new sources than individuals identifying as Republican (Jurkowitz et al., 2020 ; Gottfried et al., 2020 ).

In both Canada and the United States, low scientific quality was paired with lower-than-average sensationalism in news outlets on the populist-right (Figs. 3 F and 4F ). Sensationalism was low overall for all news outlets, but within Canada and the United States, it was lowest for the Toronto Sun and New York Post , as well as the Wall Street Journal . Although low sensationalism is generally considered beneficial, very low sensationalism combined with low scientific quality may have failed to alert readers to public-health risks and policy failures in some cases (e.g., per the measures of exposing and warning coverage in Fig. 4 ). Such trends also resulted, in part, from higher reliance on syndicated articles, especially in Canada, potentially related to structural and economic changes in news media (SI Fig. S6 ). Across the political spectrum, our results demonstrate that existing ideological perspectives may influence how information is used in reporting (Rosella et al., 2013 ). For example, news outlets at the populist-right in the United Kingdom and the United States may tend towards support of populist-right governments, demonstrating preference for those governments’ interpretation of the science, implemented policies, and use of science to justify choices made (Bennett et al., 2008 ; Grundmann and Stehr, 2012 ).

The studied news media outlets—traditional, national-level print media—have disproportionate influence on the content of other media platforms and on how that content is covered (Project for Excellence in Journalism, 2010 ; Denham, 2014 ). A better understanding of the effects of news media—or lack thereof—on public-health decision-making and public sentiment in the early stages of this pandemic can, for future pandemics or other public-health crises, increase public-health officials’ capacity to adapt communication strategies in disseminating guidance and coordinating responses of health system stakeholders (Laing, 2011 ; Rosella et al., 2013 ; Klemm et al., 2016 ; Hoffman and Justicz, 2016 ; Pieri, 2019 ). Such understanding is crucial as the impacts of the policy actions themselves accumulate. The findings of this study point to complex interactions among scientific evidence on public-health risks and response measures, societal politicization of the science, and the scientific quality and sensationalism of media reporting. An inherent tension may exist: tendencies towards low sensationalism, especially combined with low scientific quality, may in some cases lead to characterization of public-health threats and policy failures as less extraordinary and relevant than they actually are.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information .

Adeel AB, Catalano M, Catalano O, et al (2020) COVID-19 policy response and the rise of the sub-national governments. Can Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.3138/cpp.2020-101

Anderson B, Coletto D (2017) Canadian news media and “fake news” under a microscope. In: Abacus Data. https://abacusdata.ca/canadian-news-media-and-fake-news-under-a-microscope/ . Accessed 25 Aug 2020

Antoine J-Y, Villaneau J, Lefeuvre A (2014) Weighted Krippendorff’s alpha is a more reliable metrics for multi- coders ordinal annotations: experimental studies on emotion, opinion and coreference annotation. In: Proceedings of the 14th conference of the European chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Association for Computational Linguistics, Gotenborg, Sweden, pp. 550–559

Austen I (2020) Canada’s largest newspaper changes hands amid vow to keep liberal voice. N. Y. Times

Ball P, Maxmen A (2020) The epic battle against coronavirus misinformation and conspiracy theories. Nature 581:371–374. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01452-z

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Bennett WL, Lawrence RG, Livingston S (2008) When the press fails: political power and the news media from Iraq to Katrina. University of Chicago Press

Cameron EE, Nuzzo JB, Bell JA (2019) GHS index: global health security index: building collective action and accountability. NTI and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

CBC News (2020) Tracking the spread of coronavirus in canada and around the world. https://newsinteractives.cbc.ca/coronavirustracker/ . Accessed 25 Aug 2020

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2020) CDC COVID Data Tracker. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker . Accessed 30 Aug 2020

Cohen J (1960) A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas 20:37–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000104

Article Google Scholar

Denham BE (2014) Intermedia attribute agenda setting in the New York Times: the case of animal abuse in U.S. horse racing. Journal Mass Commun Q 91:17–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699013514415

Evanega S, Lynas M, Adams J, Smolenyak K (2020) Coronavirus misinformation: quantifying sources and themes in the COVID-19 ‘infodemic.’ Cornell Alliance for Science

Fleiss JL, Cohen J (1973) The equivalence of weighted kappa and the intraclass correlation coefficient as measures of reliability. Educ Psychol Meas 33:613–619. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447303300309

Gentzkow M, Shapiro JM (2010) What drives media slant? Evidence from U.S. daily newspapers. Econometrica 78:35–71. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA7195

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Giraudoux P, Antonietti J-P, Beale C, et al (2018) pgirmess: spatial analysis and data mining for field ecologists. R package version 1.6.9 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pgirmess

Gottfried J, Walker M, Mitchell A (2020) Americans’ views of the news media during the Coronavirus outbreak. Pew Research Center

Government of Canada (2016) Canada’s health care system. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canada-health-care-system.html . Accessed 18 Oct 2020

Green J, Edgerton J, Naftel D et al. (2020) Elusive consensus: polarization in elite communication on the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci Adv 6:eabc2717. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abc2717

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Grossman G, Kim S, Rexer JM, Thirumurthy H (2020) Political partisanship influences behavioral responses to governors’ recommendations for COVID-19 prevention in the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:24144–24153. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2007835117

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Grundmann R, Stehr N (2012) The power of scientific knowledge: from research to public policy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Book Google Scholar

Hallgren KA (2012) Computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: an overview and tutorial. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol 8:23–34. https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.08.1.p023

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hart PS, Chinn S, Soroka S (2020) Politicization and polarization in COVID-19 news coverage. Sci Commun 42:679–697. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547020950735

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hoffman SJ, Justicz V (2016) Automatically quantifying the scientific quality and sensationalism of news records mentioning pandemics: validating a maximum entropy machine-learning model. J Clin Epidemiol 75:47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.12.010

Holtz D, Zhao M, Benzell SG et al. (2020) Interdependence and the cost of uncoordinated responses to COVID-19. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:19837–19843. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2009522117

Hönnige C, Nyhuis D, Meyer P et al. (2020) Dominating the debate: visibility bias and mentions of British MPs in newspaper reporting on Brexit. Polit Res Exch 2:1788955. https://doi.org/10.1080/2474736X.2020.1788955

Jurkowitz M, Mitchell A, Shearer E, Walker M (2020) U.S. media polarization and the 2020 election: a nation divided. Pew Research Center

Klemm C, Das E, Hartmann T (2016) Swine flu and hype: a systematic review of media dramatization of the H1N1 influenza pandemic. J Risk Res 19:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2014.923029

Lacy S, Riffe D, Stoddard S et al. (2001) Sample size for newspaper content analysis in multi-year studies. J Mass Commun Q 78:836–45

Google Scholar

Laing A (2011) The H1N1 crisis: roles played by government communicators, the public and the media. J Prof Commun 1:123–149. https://doi.org/10.15173/jpc.v1i1.88

Article ADS Google Scholar

Lincoln M (2020) Study the role of hubris in nations’ COVID-19 response. Nature 585:325–325. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-02596-8

Mitchell A, Simmons K, Matsa KE, et al (2018) In Western Europe, public attitudes toward news media more divided by populist views than left-right ideology. Pew Research Center

Molek-Kozakowska K (2013) Towards a pragma-linguistic framework for the study of sensationalism in news headlines. Discourse Commun 7:173–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481312471668

Oxman AD, Guyatt GH, Cook DJ et al. (1993) An index of scientific quality for health reports in the lay press. J Clin Epidemiol 46:987–1001. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(93)90166-x

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Pieri E (2019) Media framing and the threat of global pandemics: the Ebola crisis in UK media and policy response. Sociol Res Online 24:73–92

Project for Excellence in Journalism (2010) How news happens: a study of the news ecosystem of one American city. Pew Research Center

Public Health England, NHSX (2020) Coronavirus (COVID-19) in the UK. https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk . Accessed 2 Oct 2020

Puglisi R, Snyder JM (2015) The balanced US press. J Eur Econ Assoc 13:240–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeea.12101

R Core Team (2020) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria

Reintjes R, Das E, Klemm C et al. (2016) “Pandemic public health paradox”: time series analysis of the 2009/10 influenza A / H1N1 epidemiology, media attention, risk perception and public reactions in 5 European countries. PLoS ONE 11:e0151258. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0151258

Riffe D, Aust CF, Lacy SR (2016) The effectiveness of random, consecutive day and constructed week sampling in newspaper content analysis. Journal Q 70:133–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769909307000115

Rosella LC, Wilson K, Crowcroft NS et al. (2013) Pandemic H1N1 in Canada and the use of evidence in developing public health policies–A policy analysis. Soc Sci Med 83:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.009

Roser M, Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, Hasell J (2020) Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus . Accessed 30 Aug 2020

Thorp HH (2020) Trump lied about science. Science 369:1409. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abe7391

Tran D, Dolgun A, Demirhan H (2020) Weighted inter-rater agreement measures for ordinal outcomes. Commun Stat-Simul Comput 49:989–1003. https://doi.org/10.1080/03610918.2018.1490428

World Health Organization (WHO) (2020a) Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 . Accessed 7 Jun 2020

World Health Organization (WHO) (2020b) Timeline of WHO’s response to COVID-19. https://www.who.int/news/item/29-06-2020-covidtimeline . Accessed 5 Jun 2020

Zhang R, Li Y, Zhang AL et al. (2020) Identifying airborne transmission as the dominant route for the spread of COVID-19. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:14857–14863. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2009637117

Download references

Acknowledgements

S. Damouras provided advising on methods of statistical analysis, and J. Niemann formatted references. Funding for this work was provided by the University of Toronto Scarborough Department of Physical and Environmental Sciences and the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Environmental Science and Policy, Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA

Katharine J. Mach & Rosalind Donald

Leonard and Jayne Abess Center for Ecosystem Science and Policy, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL, USA

Katharine J. Mach

Department of Physical and Environmental Sciences, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Raúl Salas Reyes, Brian Pentz, Clarissa A. Costa, Sandip G. Cruz, Kerronia E. Thomas & Nicole Klenk

Department of Geography and Planning, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Jennifer Taylor

Aspen Global Change Institute, Basalt, CO, USA

James C. Arnott

Earth and Environmental Sciences Area, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, USA

Kripa Jagannathan

School for Environment and Sustainability, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, USA

Christine J. Kirchhoff

Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Laura C. Rosella

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors conceived the analysis. KJM, RSR, BP, JT, CAC, SGC, KET, and NK designed the methods of analysis with review by all authors. RSR, BP, JT, CAC, SGC, and KET collected data. KJM, RSR, BP, and JT performed analysis of data and developed visualizations of data. KJM, RSR, BP, JT, and NK drafted the manuscript with review and edits from all authors.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Katharine J. Mach .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information, si appendix dataset s1, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Mach, K.J., Salas Reyes, R., Pentz, B. et al. News media coverage of COVID-19 public health and policy information. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8 , 220 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00900-z

Download citation

Received : 06 January 2021

Accepted : 15 September 2021

Published : 28 September 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00900-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Covid-19 pandemic and vaccination skepticism.

- Abdul Latif Anas

- Mashudu Salifu

- Hanan Lassen Zakaria

Human Arenas (2023)

Local TV News Coverage of Racial Disparities in COVID-19 During the First Wave of the Pandemic, March–June 2020

- Elizabeth K. Farkouh

- Jeff Niederdeppe

Race and Social Problems (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Research News

NYU ranked #8 research institution in North America—up from #25 in 2016—based on increase in articles in top science journals

Labor trafficking affects children in industries ranging from domestic work to forced criminality, entertainment, and agriculture.

Leading scholars in engineering and biostatistics receive lifetime honor recognizing extraordinary contributions to science

There’s new evidence from a researcher at NYU Silver that nonstandard hours, a growing phenomenon, can take a serious toll over the course of a person's working years.

NYU historian Stefanos Geroulanos says we need to ‘take responsibility for what humanity is becoming,’ rather than looking to prehistory for easy answers.

Study reveals how small environmental changes can have a major impact on the shapes of cells and organisms

Study is fourth published in past seven months by NYU Wagner’s Patricia Satterstrom on interdisciplinary teamwork and collaborating across power dimensions

New “quasar catalog” serves as a 3D history book of the universe

Carter Journalism Institute undergrads research historical coverage of racial killings to improve present-day reporting on today’s bias crimes

Identifying animals resilient to DNA damage may provide clues for human risk factors

AI Index Report

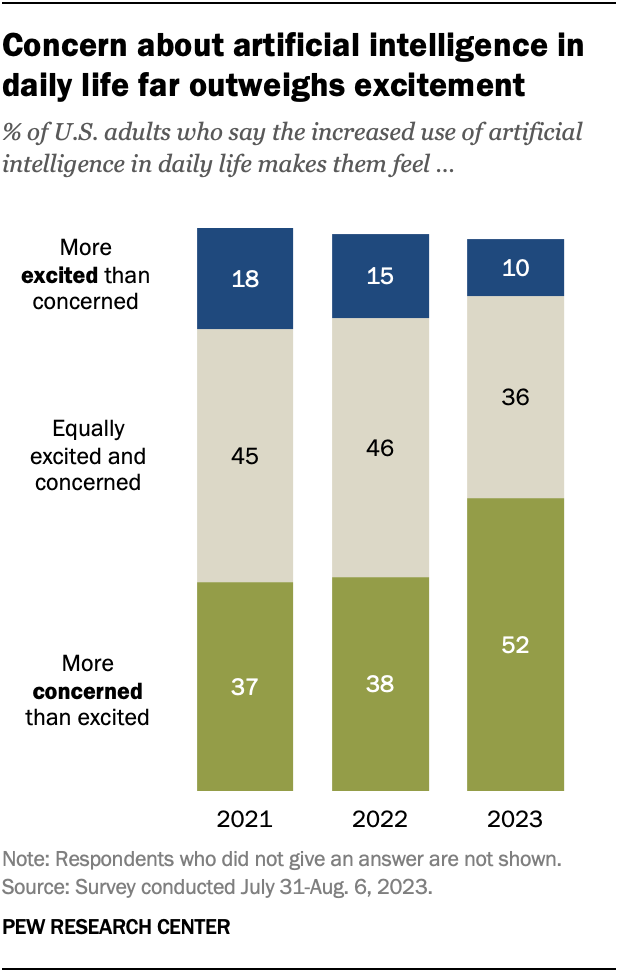

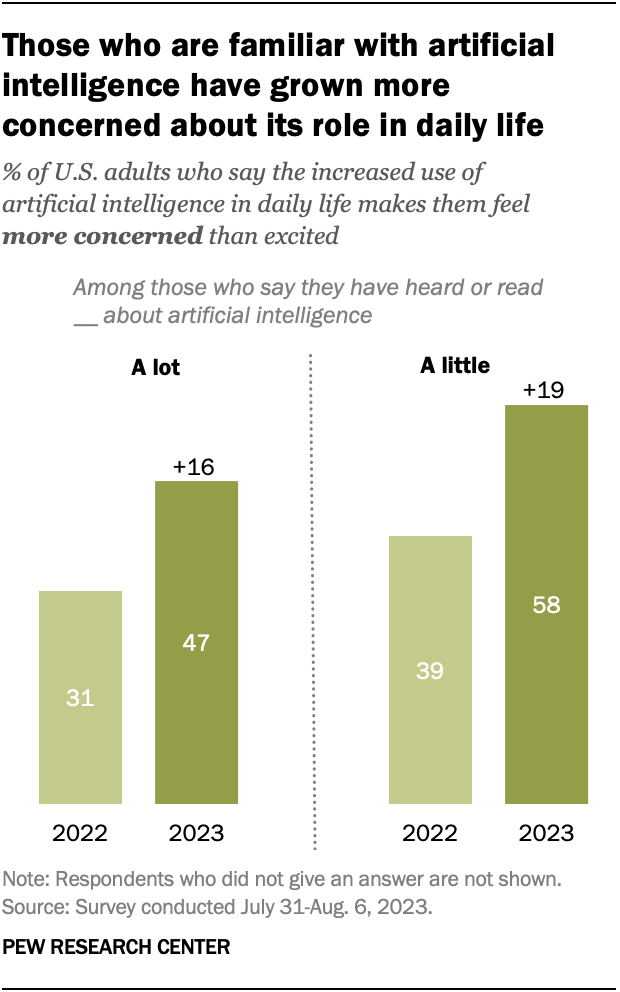

Welcome to the seventh edition of the AI Index report. The 2024 Index is our most comprehensive to date and arrives at an important moment when AI’s influence on society has never been more pronounced. This year, we have broadened our scope to more extensively cover essential trends such as technical advancements in AI, public perceptions of the technology, and the geopolitical dynamics surrounding its development. Featuring more original data than ever before, this edition introduces new estimates on AI training costs, detailed analyses of the responsible AI landscape, and an entirely new chapter dedicated to AI’s impact on science and medicine.

Read the 2024 AI Index Report

The AI Index report tracks, collates, distills, and visualizes data related to artificial intelligence (AI). Our mission is to provide unbiased, rigorously vetted, broadly sourced data in order for policymakers, researchers, executives, journalists, and the general public to develop a more thorough and nuanced understanding of the complex field of AI.

The AI Index is recognized globally as one of the most credible and authoritative sources for data and insights on artificial intelligence. Previous editions have been cited in major newspapers, including the The New York Times, Bloomberg, and The Guardian, have amassed hundreds of academic citations, and been referenced by high-level policymakers in the United States, the United Kingdom, and the European Union, among other places. This year’s edition surpasses all previous ones in size, scale, and scope, reflecting the growing significance that AI is coming to hold in all of our lives.

Steering Committee Co-Directors

Ray Perrault

Steering committee members.

Erik Brynjolfsson

John Etchemendy

Katrina Ligett

Terah Lyons

James Manyika

Juan Carlos Niebles

Vanessa Parli

Yoav Shoham

Russell Wald

Staff members.

Loredana Fattorini

Nestor Maslej

Letter from the co-directors.