New cause of diabetes discovered, offering potential target for new classes of drugs to treat the disease

Researchers at Case Western Reserve University and University Hospitals have identified an enzyme that blocks insulin produced in the body -- a discovery that could provide a new target to treat diabetes.

Their study, published Dec. 5 in the journal Cell, focuses on nitric oxide, a compound that dilates blood vessels, improves memory, fights infection and stimulates the release of hormones, among other functions. How nitric oxide performs these activities had long been a mystery.

The researchers discovered a novel "carrier" enzyme (called SNO-CoA-assisted nitrosylase, or SCAN) that attaches nitric oxide to proteins, including the receptor for insulin action.

They found that the SCAN enzyme was essential for normal insulin action, but also discovered heightened SCAN activity in diabetic patients and mice with diabetes. Mouse models without the SCAN enzyme appeared to be shielded from diabetes, suggesting that too much nitric oxide on proteins may be a cause of such diseases.

"We show that blocking this enzyme protects from diabetes, but the implications extend to many diseases likely caused by novel enzymes that add nitric oxide," said the study's lead researcher Jonathan Stamler, the Robert S. and Sylvia K. Reitman Family Foundation Distinguished Professor of Cardiovascular Innovation at the Case Western Reserve School of Medicine and president of Harrington Discovery Institute at University Hospitals. "Blocking this enzyme may offer a new treatment."

Given the discovery, next steps could be to develop medications against the enzyme, he said.

The research team included Hualin Zhou and Richard Premont, both from Case Western Reserve School of Medicine and University Hospitals, and students Zack Grimmett and Nicholas Venetos from the university's Medical Science Training Program.

Many human diseases, including Alzheimer's, cancer, heart failure and diabetes, are thought to be caused or accelerated by nitric oxide binding excessively to key proteins. With this discovery, Stamler said, enzymes that attach the nitric oxide become a focus.

With diabetes, the body often stops responding normally to insulin. The resulting increased blood sugar stays in the bloodstream and, over time, can cause serious health problems. Individuals with diabetes, the Centers for Disease Control reports, are more likely to suffer such conditions as heart disease, vision loss and kidney disease.

But the reason that insulin stops working isn't well understood.

Excessive nitric oxide has been implicated in many diseases, but the ability to treat has been limited because the molecule is reactive and can't be targeted specifically, Stamler said.

"This paper shows that dedicated enzymes mediate the many effects of nitric oxide," he said. "Here, we discover an enzyme that puts nitric oxide on the insulin receptor to control insulin. Too much enzyme activity causes diabetes. But a case is made for many enzymes putting nitric oxide on many proteins, and, thus, new treatments for many diseases."

- Diseases and Conditions

- Hormone Disorders

- Chronic Illness

- Alzheimer's

- Huntington's Disease

- Disorders and Syndromes

- Nitrous oxide

- Diabetes mellitus type 1

- Diabetes mellitus type 2

- Drug discovery

- Nitrogen oxide

Story Source:

Materials provided by Case Western Reserve University . Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference :

- Hua-Lin Zhou, Zachary W. Grimmett, Nicholas M. Venetos, Colin T. Stomberski, Zhaoxia Qian, Precious J. McLaughlin, Puneet K. Bansal, Rongli Zhang, James D. Reynolds, Richard T. Premont, Jonathan S. Stamler. An enzyme that selectively S-nitrosylates proteins to regulate insulin signaling . Cell , 2023; DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.11.009

Cite This Page :

Explore More

- Long Snouts Protect Foxes Diving Into Snow

- Promising Experimental Type 1 Diabetes Drug

- Giant, Prehistoric Salmon Had Tusk-Like Teeth

- Plants On the Menu of Ancient Hunter-Gatherers

- Unexpected Differences in Binary Stars: Origin

- Flexitarian: Invasive Species With Veggies

- T. Rex Not as Smart as Previously Claimed

- Asteroid Ryugu and Interplanetary Space

- Mice Think Like Babies

- Ancient Maya Blessed Their Ballcourts

Trending Topics

Strange & offbeat.

- April 24, 2024 | Quantum Computing Meets Genomics: The Dawn of Hyper-Fast DNA Analysis

- April 24, 2024 | Scientists Turn to Venus in the Search for Alien Life

- April 24, 2024 | NASA Astronauts Enter Quarantine As Boeing Starliner Test Flight Approaches

- April 23, 2024 | Peeking Inside Protons: Supercomputers Reveal Quark Secrets

- April 23, 2024 | A Cheaper and More Sustainable Lithium Battery: How LiDFOB Could Change Everything

Beyond Blood Sugar Control: New Target for Curing Diabetes Unveiled

By Helmholtz Munich March 22, 2024

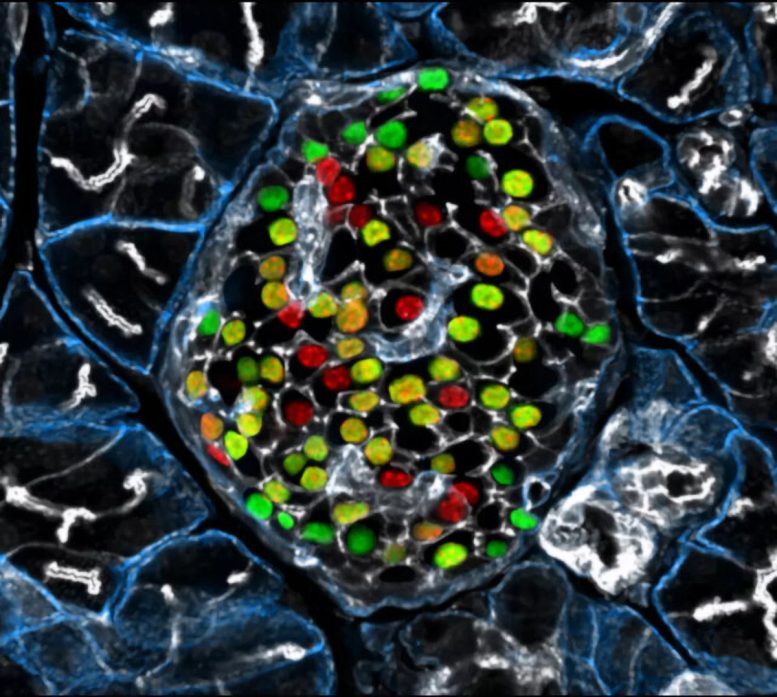

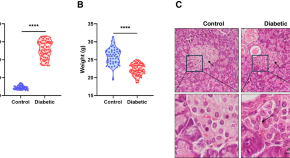

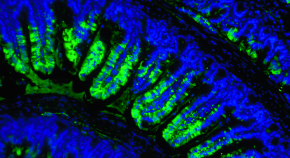

Targeting the inceptor receptor could lead to breakthrough treatments for diabetes by protecting beta cells and improving blood sugar control, with German research institutions leading this promising discovery. Insulin-producing beta cells in the islet of Langerhans. Credit: Helmholtz Munich | Erik Bader

Research focusing on the insulin -inhibitory receptor, known as inceptor, has revealed promising paths for protecting beta cells, providing optimism for therapy that directly addresses diabetes. A groundbreaking study involving mice with obesity caused by diet shows that eliminating inceptor improves glucose management. This finding encourages further investigation into inceptor as a potential therapeutic target for treating type 2 diabetes.

These findings, led by Helmholtz Munich in collaboration with the German Center for Diabetes Research, the Technical University of Munich, and the Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, drive advancements in diabetes research.

Targeting Inceptor to Combat Insulin Resistance in Beta Cells

Insulin resistance, often linked to abdominal obesity, presents a significant healthcare dilemma in our era. More importantly, the insulin resistance of beta cells contributes to their dysfunction and the transition from obesity to overt type 2 diabetes. Currently, all pharmacotherapies, including insulin supplementation, focus on managing high blood sugar levels rather than addressing the underlying cause of diabetes: beta cell failure or loss. Therefore, research into beta cell protection and regeneration is crucial and holds promising prospects for addressing the root cause of diabetes, offering potential avenues for causal treatment.

With the recent discovery of inceptor, the research group of beta cell expert Prof. Heiko Lickert has uncovered an interesting molecular target. Upregulated in diabetes, the insulin-inhibitory receptor inceptor may contribute to insulin resistance by acting as a negative regulator of this signaling pathway. Conversely, inhibiting the function of the inceptor could enhance insulin signaling – which in turn is required for overall beta cell function, survival, and compensation upon stress.

In collaboration with Prof. Timo Müller, an expert in molecular pharmacology in obesity and diabetes, the researchers explored the effects of inceptor knock-out in diet-induced obese mice. Their study aimed to determine whether inhibiting inceptor function could also enhance glucose tolerance in diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance, both critical pre-clinical stages in the progression toward diabetes. The results were now published in Nature Metabolism .

Removing Inceptor Improves Blood Sugar Levels in Obese Mice

The researchers delved into the effects of removing inceptor from all body cells in diet-induced obese mice. Interestingly, they found that mice lacking inceptor exhibited improved glucose regulation without experiencing weight loss, which was linked to increased insulin secretion in response to glucose. Next, they investigated the distribution of inceptor in the central nervous system and discovered its widespread presence in neurons. Deleting inceptor from neuronal cells also improved glucose regulation in obese mice. Ultimately, the researchers selectively removed the inceptor from the mice’s beta cells, resulting in enhanced glucose control and a slight increase in beta cell mass.

Research for Inceptor-Blocking Drugs

“Our findings support the idea that enhancing insulin sensitivity through targeting inceptor shows promise as a pharmacological intervention, especially concerning the health and function of beta cells,” says Timo Müller. Unlike intensive early-onset insulin treatments, utilizing inceptor to enhance beta cell function offers promise in alleviating the detrimental effects on blood sugar and metabolism induced by diet-induced obesity. This approach avoids the associated risks of hypoglycemia-associated unawareness and unwanted weight gain typically observed with intensive insulin therapy.

“Since inceptor is expressed on the surface of pancreatic beta cells, it becomes an accessible drug target. Currently, our laboratory is actively researching the potential of several inceptor-blocking drug classes to enhance beta cell health in pre-diabetic and diabetic mice. Looking forward, inceptor emerges as a novel and intriguing molecular target for enhancing beta cell health, not only in prediabetic obese individuals but also in patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes,” explains Heiko Lickert.

Reference: “Global, neuronal or β cell-specific deletion of inceptor improves glucose homeostasis in male mice with diet-induced obesity” by Gerald Grandl, Gustav Collden, Jin Feng, Sreya Bhattacharya, Felix Klingelhuber, Leopold Schomann, Sara Bilekova, Ansarullah, Weiwei Xu, Fataneh Fathi Far, Monica Tost, Tim Gruber, Aimée Bastidas-Ponce, Qian Zhang, Aaron Novikoff, Arkadiusz Liskiewicz, Daniela Liskiewicz, Cristina Garcia-Caceres, Annette Feuchtinger, Matthias H. Tschöp, Natalie Krahmer, Heiko Lickert and Timo D. Müller, 28 February 2024, Nature Metabolism . DOI: 10.1038/s42255-024-00991-3

More on SciTechDaily

Quantum Breakthrough Reveals Superconductor’s Hidden Nature

Novel Molecules Discovered to Combat Asthma and COVID-Related Lung Diseases

Orbital Engineering, Yale Engineers Change Electron Trajectories

Finding and Erasing Quantum Computing Errors in Real-Time

“Glow-in-the-Dark” Proteins: The Future of Viral Disease Detection?

A black hole – a million times as bright as our sun – offers potential clue to reionization of universe.

Risk Factors for Falls in Older Americans Identified – A Growing Public Health Concern

Common Fireworks Emit Toxic Metals Into the Air – Damage Human Cells and Animal Lungs

1 comment on "beyond blood sugar control: new target for curing diabetes unveiled".

Interesting study and hopefully another tool which will apply to diabetic patients.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Email address is optional. If provided, your email will not be published or shared.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Cornell Chronicle

- Architecture & Design

- Arts & Humanities

- Business, Economics & Entrepreneurship

- Computing & Information Sciences

- Energy, Environment & Sustainability

- Food & Agriculture

- Global Reach

- Health, Nutrition & Medicine

- Law, Government & Public Policy

- Life Sciences & Veterinary Medicine

- Physical Sciences & Engineering

- Social & Behavioral Sciences

- Coronavirus

- News & Events

- Public Engagement

- New York City

- Photos of the Week

- Big Red Sports

- Freedom of Expression

- Student Life

- University Statements

- Around Cornell

- All Stories

- In the News

- Expert Quotes

- Cornellians

Large-scale study reveals new genetic details of diabetes

By wynne parry weill cornell medicine.

In experiments of unprecedented scale, investigators at Weill Cornell Medicine and the National Institutes of Health have revealed new aspects of the complex genetics behind Type 2 diabetes. Through these discoveries, and by providing a template for future studies, this research furthers efforts to better understand and ultimately treat this common metabolic disease.

Previous studies have generally examined the influence of individual genes. In research described Oct. 18 in Cell Metabolism, senior co-author Shuibing Chen , the Kilts Family Professor of Surgery at Weill Cornell Medicine, working alongside senior co-author Dr. Francis Collins , a senior investigator at the Center for Precision Health Research within the National Human Genome Research Institute of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, took a more comprehensive approach. Together, they looked at the contribution of 20 genes in a single effort.

“It’s very difficult to believe all these diabetes-related genes act independently of each other,” Chen said. By using a combination of technologies, the team examined the effects of shutting each down. By comparing the consequences for cell behavior and genetics, she said, “we found some common themes.”

As with other types of diabetes, Type 2 diabetes occurs when sugar levels in the blood are too high. In Type 2 diabetes, this happens in part because specialized cells in the pancreas, known as β-cells, don’t produce enough insulin, a hormone that tells cells to take sugar out of the blood for use as an energy source. Over time, high levels of blood sugar damage tissues and cause other problems, such as heart and kidney disease. According to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 9% of adults in the United States have been diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes.

Both genetic and environmental factors, such as obesity and chronic stress, can increase risk for it. Yet evaluating the role of the genetic contributors alone is a massive project. So far, researchers have identified more than 290 locations within the genome where changes to DNA can raise the likelihood of developing the disease. Some of these locations fall within known genes, but most are found in regions that regulate the expression of nearby genes.

For the new research, the team focused on 20 genes clearly identified as contributors. They began their investigation by using the gene editing system CRISPR-Cas9 to shut down these genes, one at a time, within 20 sets of identical stem cells.

These stem cells had the potential to generate any kind of mature cell, but the researchers coaxed them into becoming insulin-producing β-cells. They then examined the effects of losing each gene on five traits related to insulin production and the health of β-cells. They also documented the accompanying changes in gene expression and the accessibility of DNA for expression.

To make sense of the massive amount of data they collected, the team developed their own computational models to analyze it, leading to several discoveries: By comparing the effects of all 20 mutations on β-cells, they identified four additional genes, each representing a newly discovered pathway that contributes to insulin production. They also found that, of the original 20 genes, only one, called HNF4A, contributed to all five traits, apparently by acting as a master controller that regulates the activity of other genes. In one specific example, they explained how a small variation, located in a space between genes, contributes to the risk of diabetes by interfering with HNF4A’s ability to regulate nearby genes.

Ultimately, this study and others like it hold the promise of benefiting patients, Collins said. “We need to understand all the genetic and environmental factors involved so we can do a better job of preventing diabetes, and to develop new ideas about how to effectively treat it.”

Collins and Chen note that their approach may have relevance beyond diabetes, to other common diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Crohn’s disease, that involve many genetic factors.

The work reported in this newsroom story was supported in part by the United States’ National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the American Diabetes Association.

Many Weill Cornell Medicine physicians and scientists maintain relationships and collaborate with external organizations to foster scientific innovation and provide expert guidance. The institution makes these disclosures public to ensure transparency. For this information, see the profile for Shuibing Chen .

Wynne Parry is a freelance writer for Weill Cornell Medicine.

Media Contact

Krystle lopez.

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

You might also like

Gallery Heading

These New Developments Could Make Living With Type 2 Diabetes More Manageable

E xperts often talk about the “burden” of a disease or illness. The word acts as a tidy container for all the unpleasantness people with that condition may experience—from their symptoms, to the cost of their care, to the restrictions imposed on their lifestyle, to the health complications that may arise. For people with Type 2 diabetes , this burden can be high.

Routine management of Type 2 diabetes often involves major changes to one’s diet and physical activity . And for many, especially those taking insulin to manage their blood sugar, the disease can necessitate daily blood-glucose monitoring, a process that entails pricking a finger to draw blood and then dabbing that blood onto a glucose monitor’s test strip. Doing this several times a week—month after month—can present overlapping challenges. According to a 2013 survey in the journal Diabetes Spectrum, people find finger-prick glucose monitoring to be painful, and the results can be confusing or unhelpful.

“Patients don’t want to prick their fingers, and they come in all the time and say, ‘I’m tired of this,’” says Dr. Francisco Pasquel, a diabetes specialist and associate professor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta.

But relief is on the way. Continuous glucose monitors, or CGMs, are small devices-—often about the size of a quarter-—that use a small under-the-skin needle to continuously monitor blood-glucose levels. This information can be transmitted—in some cases wirelessly and automatically—to a smartphone app or other device. “You can look at glucose levels for a single point in time, but you can also look at trends in values over time,” says Dr. Roy Beck, medical director of the nonprofit Jaeb Center for Health Research in Tampa. Beck’s work has found that continuous glucose monitoring may provide a number of benefits for people with Type 2 diabetes.

These monitors are just one of several new advancements in Type 2 diabetes care and management. From connected technologies to new drug treatments, medical science is making steady and sometimes life-changing progress in the treatment of this condition. Here, experts describe some of the latest and greatest developments.

Continuous glucose monitors

People with Type 1 diabetes typically have to check their blood-sugar levels on a daily basis, or even multiple times each day. Because testing is such a big part of managing that disease, the research on continuous glucose monitors started with these patients. That work has shown that CGMs provide multiple benefits, including reduced hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) levels, which is an important measure of healthy blood glucose. Continuous glucose monitors are now being studied in people with Type 2 diabetes, and research points to multiple benefits.

For a study published in 2021 in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Beck and his colleagues compared continuous glucose monitoring to standard finger-prick tests among people with Type 2 diabetes who were using insulin. They found that continuous monitoring was associated with a significantly greater drop in HbA1c. They also found that continuous monitoring helped people avoid risky and severe drops in blood sugar (a.k.a. hypoglycemia). “It’s pretty clear that there’s a benefit for people with Type 2 diabetes who are using insulin,” he says.

More than 90% of people with diabetes have Type 2 diabetes, and Beck says that roughly 30% of these people are using insulin. In other words, there are many people with Type 2 diabetes who stand to benefit from continuous glucose monitoring. However, use of these monitors is still mostly confined to people with Type 1 diabetes. “Use is slowly increasing in Type 2 patients, but I think it’s still too low considering this is a non-pharmacological approach”—something many people prefer because it avoids the side effects of medications—“that can help people,” he says.

Even for people with Type 2 diabetes who are not taking insulin, Beck says that continuous glucose monitoring could be helpful. “There’s a need for more studies to prove it, but it makes sense that it would likely have benefits,” he says. For example, monitoring blood sugar in real time could help people make diet or lifestyle changes that reduce their risks for long-term health complications. “Normally, blood glucose following a meal shouldn’t go above 140 [mg/dL],” he says. But based on factors like diet, meal timing, and exercise habits, someone with Type 2 diabetes may experience post-meal blood-sugar spikes that surpass 200 or even 300 mg/dL. These spikes could cause few symptoms or short-term consequences, Beck says, but over time they can contribute to the development of common diabetes-related complications such as kidney failure, heart disease, or diabetic retinopathy (an eye condition that can cause blurry vision or blindness). “The first time people use these continuous monitors, it can be a real eye-opener,” he adds. “I think they could be most helpful for self-management, and Type 2 diabetes is a disease where self-management through diet and exercise can make a huge difference.”

Other experts second this. “Patients using these devices can receive a graph of their glucose values over time, which helps them understand the effects of nutrition on glucose control, or how they could modify their exercise to make improvements,” says Dr. Ilias Spanakis, an associate professor of medicine in the division of endocrinology, diabetes, and nutrition at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

For patients who are reliant on insulin to manage their blood glucose, combining continuous glucose monitors with insulin pumps—devices that automatically inject insulin as needed—could also lead to major improvements. “Smart algorithms that connect the two can automatically adjust glucose based on glucose values,” Spanakis says. This is already possible, and it’s likely to become much more commonplace, he adds.

For many people with diabetes, continuous glucose monitoring could provide a safer and simpler path forward.

Read More: The Link Between Type 2 Diabetes and Psychiatric Disorders

Bariatric surgery for Type 2 diabetes

Historically, bariatric (weight-loss) surgery has been used primarily to help people manage severe obesity, which the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines as a BMI of 40 or higher. Many people who are severely obese also have diabetes, and research has found that these surgical procedures can help reduce the burden of Type 2 diabetes or even send it into remission.

A 2018 study from researchers at the University of Oklahoma found that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery, a common bariatric procedure, vastly outperformed typical medical management techniques—such as diet changes, doctor’s visits, and prescription drugs—among people with Type 2 diabetes. Surgery led to diabetes remission in roughly 28% of patients, compared with a remission rate of just 4% among the non-surgery group, according to the study results. More research has found that bariatric surgery may effectively send Type 2 diabetes into remission.

“Surgery does not just lead to weight loss, but also to an improvement in glycemic control, which happens even before the weight loss occurs,” says Emory’s Pasquel, who has published work on the benefits of bariatric surgery for people with Type 2 diabetes. Exactly how the surgery does this isn’t well understood, he says. However, bariatric surgery affects appetite, food intake, caloric absorption, and multiple neuroendocrine pathways—all of which could contribute to its beneficial actions for people with Type 2 diabetes.

In the future, Pasquel says these procedures are likely to become more commonplace even for people with Type 2 diabetes who are not severely obese.

More from TIME

New pharmaceutical drugs.

There are a lot of different diabetes drugs on the market, each with its own risks and benefits. But experts say two types are emerging as potential “game changers” when it comes to Type 2 diabetes treatment.

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) is a hormone released in the gut during digestion—one that plays a role in blood-sugar homeostasis. A class of drugs known as GLP-1 receptor agonists can interact with GLP-1 receptors in ways that lower appetite, slow digestion, and provide other benefits for people with Type 2 diabetes. These GLP-1 drugs aren’t new. But Pasquel says the latest versions are different in that they work on two different receptors, not one. “Recent evidence shows that activating both receptors has a remarkable impact on weight loss and glycemic control,” he says. Especially for people with Type 2 diabetes who are at high risk for heart or arterial disease, he says that these new drugs seem to be a big upgrade over previous medications.

A second category of drug has also emerged as a standout in the treatment of Type 2 diabetes. Known as sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors, these drugs help the kidneys remove sugar from a person’s blood. Not only does this improve blood-sugar control in people with Type 2 diabetes, but it also helps protect them from heart failure and kidney disease—two common and serious complications. Pasquel says these drugs are so effective that they’re now being used in people with heart failure or kidney disease who do not have Type 2 diabetes.

Read More: The Truth About Fasting and Type 2 Diabetes

Emerging ways to think about weight loss

Experts have long understood that weight loss can help people reduce their Type 2 diabetes symptoms and risks . This recognition has led to research on a number of weight-loss diets . More research is needed, but some of the latest studies suggest that fasting plans—in particular, intermittent fasting—may be particularly beneficial for people with Type 2 diabetes.

Intermittent fasting involves cutting out calorie-containing foods and drinks for an extended period of time—anywhere from 12 hours to two days depending on the approach a person chooses. A 2019 research review in the journal Nutrients found that intermittent fasting promotes weight loss, increases insulin sensitivity, and reduces insulin levels in the blood. All of this is helpful for people with Type 2 diabetes. “Essentially, fasting is doing what we prescribe diabetes medications to do, which is to improve insulin sensitivity,” says Benjamin Horne, director of cardiovascular and genetic epidemiology at Intermountain Healthcare in Utah.

It’s not yet clear which form of intermittent fasting is best. But Horne says that time-restricted eating—a type of fasting that involves squeezing all the day’s calories into single six- or eight-hour feeding windows—is leading the pack, largely because patients are able to stick with it.

There are more new advancements in Type 2 diabetes care. The interventions described here—from continuous glucose monitors to novel drugs—are some of the most promising, but they have company. It’s safe to say that, looking ahead, more people with Type 2 diabetes will be able to effectively manage or mitigate their symptoms.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

How old is too old to run?

America’s graying. We need to change the way we think about age.

Can we talk?

“When my son was diagnosed [with Type 1], I knew nothing about diabetes. I changed my research focus, thinking, as any parent would, ‘What am I going to do about this?’” says Douglas Melton.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Breakthrough within reach for diabetes scientist and patients nearest to his heart

Harvard Correspondent

100 years after discovery of insulin, replacement therapy represents ‘a new kind of medicine,’ says Stem Cell Institute co-director Douglas Melton, whose children inspired his research

When Vertex Pharmaceuticals announced last month that its investigational stem-cell-derived replacement therapy was, in conjunction with immunosuppressive therapy, helping the first patient in a Phase 1/2 clinical trial robustly reproduce his or her own fully differentiated pancreatic islet cells, the cells that produce insulin, the news was hailed as a potential breakthrough for the treatment of Type 1 diabetes. For Harvard Stem Cell Institute Co-Director and Xander University Professor Douglas Melton, whose lab pioneered the science behind the therapy, the trial marked the most recent turning point in a decades-long effort to understand and treat the disease. In a conversation with the Gazette, Melton discussed the science behind the advance, the challenges ahead, and the personal side of his research. The interview was edited for clarity and length.

Douglas Melton

GAZETTE: What is the significance of the Vertex trial?

MELTON: The first major change in the treatment of Type 1 diabetes was probably the discovery of insulin in 1920. Now it’s 100 years later and if this works, it’s going to change the medical treatment for people with diabetes. Instead of injecting insulin, patients will get cells that will be their own insulin factories. It’s a new kind of medicine.

GAZETTE: Would you walk us through the approach?

MELTON: Nearly two decades ago we had the idea that we could use embryonic stem cells to make functional pancreatic islets for diabetics. When we first started, we had to try to figure out how the islets in a person’s pancreas replenished. Blood, for example, is replenished routinely by a blood stem cell. So, if you go give blood at a blood drive, your body makes more blood. But we showed in mice that that is not true for the pancreatic islets. Once they’re removed or killed, the adult body has no capacity to make new ones.

So the first important “a-ha” moment was to demonstrate that there was no capacity in an adult to make new islets. That moved us to another source of new material: stem cells. The next important thing, after we overcame the political issues surrounding the use of embryonic stem cells, was to ask: Can we direct the differentiation of stem cells and make them become beta cells? That problem took much longer than I expected — I told my wife it would take five years, but it took closer to 15. The project benefited enormously from undergraduates, graduate students, and postdocs. None of them were here for 15 years of course, but they all worked on different steps.

GAZETTE: What role did the Harvard Stem Cell Institute play?

MELTON: This work absolutely could not have been done using conventional support from the National Institutes of Health. First of all, NIH grants came with severe restrictions and secondly, a long-term project like this doesn’t easily map to the initial grant support they give for a one- to three-year project. I am forever grateful and feel fortunate to have been at a private institution where philanthropy, through the HSCI, wasn’t just helpful, it made all the difference.

I am exceptionally grateful as well to former Harvard President Larry Summers and Steve Hyman, director of the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research at the Broad Institute, who supported the creation of the HSCI, which was formed specifically with the idea to explore the potential of pluripotency stem cells for discovering questions about how development works, how cells are made in our body, and hopefully for finding new treatments or cures for disease. This may be one of the first examples where it’s come to fruition. At the time, the use of embryonic stem cells was quite controversial, and Steve and Larry said that this was precisely the kind of science they wanted to support.

GAZETTE: You were fundamental in starting the Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology. Can you tell us about that?

MELTON: David Scadden and I helped start the department, which lives in two Schools: Harvard Medical School and the Faculty of Arts and Science. This speaks to the unusual formation and intention of the department. I’ve talked a lot about diabetes and islets, but think about all the other tissues and diseases that people suffer from. There are faculty and students in the department working on the heart, nerves, muscle, brain, and other tissues — on all aspects of how the development of a cell and a tissue affects who we are and the course of disease. The department is an exciting one because it’s exploring experimental questions such as: How do you regenerate a limb? The department was founded with the idea that not only should you ask and answer questions about nature, but that one can do so with the intention that the results lead to new treatments for disease. It is a kind of applied biology department.

GAZETTE: This pancreatic islet work was patented by Harvard and then licensed to your biotech company, Semma, which was acquired by Vertex. Can you explain how this reflects your personal connection to the research?

MELTON: Semma is named for my two children, Sam and Emma. Both are now adults, and both have Type 1 diabetes. My son was 6 months old when he was diagnosed. And that’s when I changed my research plan. And my daughter, who’s four years older than my son, became diabetic about 10 years later, when she was 14.

When my son was diagnosed, I knew nothing about diabetes and had been working on how frogs develop. I changed my research focus, thinking, as any parent would, “What am I going to do about this?” Again, I come back to the flexibility of Harvard. Nobody said, “Why are you changing your research plan?”

GAZETTE: What’s next?

MELTON: The stem-cell-derived replacement therapy cells that have been put into this first patient were provided with a class of drugs called immunosuppressants, which depress the patient’s immune system. They have to do this because these cells were not taken from that patient, and so they are not recognized as “self.” Without immunosuppressants, they would be rejected. We want to find a way to make cells by genetic engineering that are not recognized as foreign.

I think this is a solvable problem. Why? When a woman has a baby, that baby has two sets of genes. It has genes from the egg, from the mother, which would be recognized as “self,” but it also has genes from the father, which would be “non-self.” Why does the mother’s body not reject the fetus? If we can figure that out, it will help inform our thinking about what genes to change in our stem cell-derived islets so that they could go into any person. This would be relevant not just to diabetes, but to any cells you wanted to transplant for liver or even heart transplants. It could mean no longer having to worry about immunosuppression.

Share this article

You might like.

No such thing, specialist says — but when your body is trying to tell you something, listen

Experts say instead of disability, focus needs to shift to ability, health, with greater participation, economically and socially

Study finds that conversation – even online – could be an effective strategy to help prevent cognitive decline and dementia

When math is the dream

Dora Woodruff was drawn to beauty of numbers as child. Next up: Ph.D. at MIT.

Seem like Lyme disease risk is getting worse? It is.

The risk of Lyme disease has increased due to climate change and warmer temperature. A rheumatologist offers advice on how to best avoid ticks while going outdoors.

Three will receive 2024 Harvard Medal

In recognition of their extraordinary service

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

Diabetes articles from across Nature Portfolio

Diabetes describes a group of metabolic diseases characterized by high blood sugar levels. Diabetes can be caused by the pancreas not producing insulin (type 1 diabetes) or by insulin resistance (cells do not respond to insulin; type 2 diabetes).

Macrophage vesicles in antidiabetic drug action

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) are potent insulin-sensitizing drugs, but their use is accompanied by adverse side-effects. Rohm et al. now report that TZD-stimulated macrophages release miR-690-containing vesicles that improve insulin sensitization and bypass unwanted side-effects.

- Rinke Stienstra

- Eric Kalkhoven

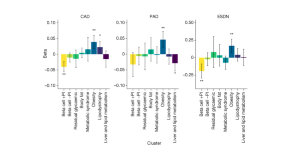

Genetic risk variants lead to type 2 diabetes development through different pathways

The largest genome-wide association study for type 2 diabetes so far, which included several ancestry groups, led to the identification of eight clusters of genetic risk variants. The clusters capture different biological pathways that contribute to the disease, and some clusters are associated with vascular complications.

Related Subjects

- Diabetes complications

- Diabetes insipidus

- Gestational diabetes

- Type 1 diabetes

- Type 2 diabetes

Latest Research and Reviews

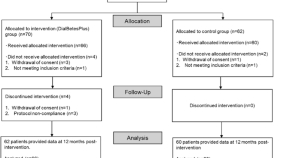

Effectiveness of DialBetesPlus, a self-management support system for diabetic kidney disease: Randomized controlled trial

- Mitsuhiko Nara

- Kazuhiko Ohe

Applications of SGLT2 inhibitors beyond glycaemic control

Here, the authors discuss the beneficial effects of sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors for a range of clinical outcomes beyond glucose lowering, including kidney and cardiovascular protection. They also discuss the need for implementation and adherence initiatives to help translate the benefits of these agents into real-world clinical outcomes.

- Daniel V. O’Hara

- Carolyn S. P. Lam

- Meg J. Jardine

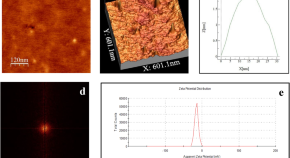

Novel PLGA-encapsulated-nanopiperine promotes synergistic interaction of p53/PARP-1/Hsp90 axis to combat ALX-induced-hyperglycemia

- Rishita Dey

- Sudatta Dey

- Asmita Samadder

Butyrate and iso-butyrate: a new perspective on nutrition prevention of gestational diabetes mellitus

- Weiling Han

- Guanghui Li

Nicotinamide Mononucleotide improves oocyte maturation of mice with type 1 diabetes

- Fucheng Guo

- Xiaoling Zhang

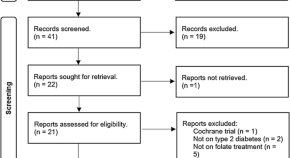

Folic acid supplementation on inflammation and homocysteine in type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Kabelo Mokgalaboni

- Given. R. Mashaba

- Sogolo. L. Lebelo

News and Comment

Repurposing a diabetes drug to treat Parkinson’s disease

In a multicenter clinical trial, patients with early-stage Parkinson’s disease treated with lixisenatide, a drug currently used for the treatment of diabetes, showed improvement in their motor scores compared with those on placebo.

- Sonia Muliyil

A novel system for non-invasive measurement of blood levels of glucose

- Olivia Tysoe

Diabetes drug slows development of Parkinson’s disease

The drug, which is in the same family as blockbuster weight-loss drugs such as Wegovy, slowed development of symptoms by a small but statistically significant amount.

Metformin acts through appetite-suppressing metabolite: Lac-Phe

- Shimona Starling

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Nih research matters.

November 7, 2023

Intermittent fasting for weight loss in people with type 2 diabetes

At a glance.

- People with obesity and type 2 diabetes lost more weight using daily periods of fasting than by trying to restrict calories over a six-month period.

- Blood sugar levels lowered in people in both groups, and no serious side effects were observed.

Around 1 in 10 Americans live with type 2 diabetes, a disease in which levels of blood glucose, or blood sugar, are too high. Diabetes can lead to serious health issues such as heart disease, nerve damage, and eye problems.

Excess weight is a major risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes, and weight loss is often recommended for those with excess weight and type 2 diabetes. Calorie restriction—reducing overall calorie intake—is a mainstay of most weight loss programs. But such regimens are very difficult to stick with over the long term.

Time-restricted eating, also called intermittent fasting, has emerged as an alternative weight loss paradigm. In this approach, the time of day during which food can be eaten is restricted, but the amount or types of food are not. Small studies have suggested that intermittent fasting is safe and promotes weight loss in people with type 2 diabetes. But these studies only tracked participants for a short period of time. They also didn’t compare the approach with traditional calorie restriction.

In a new clinical trial, an NIH-funded research team led by Dr. Krista Varady from the University of Illinois Chicago compared fasting and calorie restriction for weight loss and blood-sugar reduction. They recruited 75 people with obesity and type 2 diabetes. Of these, 70 were either Hispanic or non-Hispanic Black—two groups in the U.S. with an especially high prevalence of diabetes. The participants were randomly assigned to one of three diet groups for six months.

The fasting group could eat anything they wanted, but only between the hours of noon and 8 pm. The second group worked with a dietitian to reduce their calories by 25% of the amount needed to maintain their weight. A control group did not change their diet at all. All groups received education on healthy food choices and monitored their blood glucose closely during the study. The results were published on October 27, 2023, in JAMA Network Open .

After six months, participants in the fasting group lost an average of 3.6% percent of their body weight compared to those in the control group. In comparison, people in the calorie-restriction group did not lose a significant amount of weight compared to the control group.

Both groups had similarly healthy decreases in their average blood glucose levels. Both also had reductions in waist circumference. No serious side effects, including time outside of a safe blood glucose range, were seen in either treatment group. People in the fasting group reported that their diet was easier to adhere to than calorie restriction.

“Our study shows that time-restricted eating might be an effective alternative to traditional dieting for people who can’t do the traditional diet or are burned out on it,” Varady says. “For many people trying to lose weight, counting time is easier than counting calories.”

Some medications used to treat type 2 diabetes need adjustment for time-restricted eating. Therefore, people considering intermittent fasting should speak with a doctor before changing their eating pattern.

—by Sharon Reynolds

Related Links

- Research in Context: Obesity and Metabolic Health

- Calorie Restriction and Human Muscle Function

- Popular Diabetes Drugs Compared in Large Trial

- Diabetes Control Worsened Over the Past Decade

- Fasting Increases Health and Lifespan in Male Mice

- Factors Contributing to Higher Incidence of Diabetes for Black Americans

- Diabetes Increasing in Youths

- Benefits of Moderate Weight Loss in People with Obesity

- To Fast or Not to Fast: Does When You Eat Matter?

- Managing Diabetes: New Technologies Can Make It Easier

- Type 2 Diabetes

References: Effect of Time-Restricted Eating on Weight Loss in Adults With Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Pavlou V, Cienfuegos S, Lin S, Ezpeleta M, Ready K, Corapi S, Wu J, Lopez J, Gabel K, Tussing-Humphreys L, Oddo VM, Alexandria SJ, Sanchez J, Unterman T, Chow LS, Vidmar AP, Varady KA . JAMA Netw Open . 2023 Oct 2;6(10):e2339337. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.39337. PMID: 37889487.

Funding: NIH’s National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK); University of Illinois.

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

Type 2 Diabetes Research At-a-Glance

The ADA is committed to continuing progress in the fight against type 2 diabetes by funding research, including support for potential new treatments, a better understating of genetic factors, addressing disparities, and more. For specific examples of projects currently funded by the ADA, see below.

Greg J. Morton, PhD

University of Washington

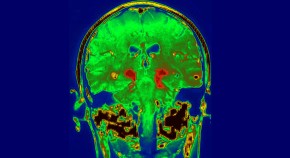

Project: Neurocircuits regulating glucose homeostasis

“The health consequences of diabetes can be devastating, and new treatments and therapies are needed. My research career has focused on understanding how blood sugar levels are regulated and what contributes to the development of diabetes. This research will provide insights into the role of the brain in the control of blood sugar levels and has potential to facilitate the development of novel approaches to diabetes treatment.”

The problem: Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is among the most pressing and costly medical challenges confronting modern society. Even with currently available therapies, the control and management of blood sugar levels remains a challenge in T2D patients and can thereby increase the risk of diabetes-related complications. Continued progress with newer, better therapies is needed to help people with T2D.

The project: Humans have special cells, called brown fat cells, which generate heat to maintain optimal body temperature. Dr. Morton has found that these cells use large amounts of glucose to drive this heat production, thus serving as a potential way to lower blood sugar, a key goal for any diabetes treatment. Dr. Morton is working to understand what role the brain plays in turning these brown fat cells on and off.

The potential outcome: This work has the potential to fundamentally advance our understanding of how the brain regulates blood sugar levels and to identify novel targets for the treatment of T2D.

Tracey Lynn McLaughlin, MD

Stanford University

Project: Role of altered nutrient transit and incretin hormones in glucose lowering after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery

“This award is very important to me personally not only because the enteroinsular axis (gut-insulin-glucose metabolism) is a new kid on the block that requires rigorous physiologic studies in humans to better understand how it contributes to glucose metabolism, but also because the subjects who develop severe hypoglycemia after gastric bypass are largely ignored in society and there is no treatment for this devastating and very dangerous condition.”

The problem: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery is the single-most effective treatment for type 2 diabetes, with persistent remission in 85% of cases. However, the underlying ways by which the surgery improves glucose control is not yet understood, limiting the ability to potentially mimic the surgery in a non-invasive way. Furthermore, a minority of RYGB patients develop severe, disabling, and life-threatening low-blood sugar, for which there is no current treatment.

The project: Utilizing a unique and rigorous human experimental model, the proposed research will attempt to gain a better understanding on how RYGB surgery improves glucose control. Dr. McLaughlin will also test a hypothesis which she believes could play an important role in the persistent low-blood sugar that is observed in some patients post-surgery.

The potential outcome: This research has the potential to identify novel molecules that could represent targets for new antidiabetic therapies. It is also an important step to identifying people at risk for low-blood sugar following RYGB and to develop postsurgical treatment strategies.

Rebekah J. Walker, PhD

Medical College of Wisconsin

Project: Lowering the impact of food insecurity in African Americans with type 2 diabetes

“I became interested in diabetes research during my doctoral training, and since that time have become passionate about addressing social determinants of health and health disparities, specifically in individuals with diabetes. Living in one of the most racially segregated cities in the nation, the burden to address the needs of individuals at particularly high risk of poor outcomes has become important to me both personally and professionally.”

The problem: Food insecurity is defined as the inability to or limitation in accessing nutritionally adequate food and may be one way to address increased diabetes risk in high-risk populations. Food insecure individuals with diabetes have worse diabetes outcomes and have more difficulty following a healthy diet compared to those who are not food insecure.

The project: Dr. Walker’s study will gather information to improve and then will test an intervention to improve blood sugar control, dietary intake, self-care management, and quality of life in food insecure African Americans with diabetes. The intervention will include weekly culturally appropriate food boxes mailed to the participants and telephone-delivered diabetes education and skills training. It will be one of the first studies focused on the unique needs of food insecure African American populations with diabetes using culturally tailored strategies.

The potential outcome: This study has the potential to guide and improve policies impacting low-income minorities with diabetes. In addition, Dr. Walker’s study will help determine if food supplementation is important in improving diabetes outcomes beyond diabetes education alone.

Donate Today and Change Lives!

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- Your Health

- Treatments & Tests

- Health Inc.

- Public Health

How to Thrive as You Age

A cheap drug may slow down aging. a study will determine if it works.

Allison Aubrey

A drug taken by millions of people to control diabetes may do more than lower blood sugar.

Research suggests metformin has anti-inflammatory effects that could help protect against common age-related diseases including heart disease, cancer, and cognitive decline.

Scientists who study the biology of aging have designed a clinical study, known as The TAME Trial, to test whether metformin can help prevent these diseases and promote a longer healthspan in healthy, older adults.

Michael Cantor, an attorney, and his wife Shari Cantor , the mayor of West Hartford, Connecticut both take metformin. "I tell all my friends about it," Michael Cantor says. "We all want to live a little longer, high-quality life if we can," he says.

Michael Cantor started on metformin about a decade ago when his weight and blood sugar were creeping up. Shari Cantor began taking metformin during the pandemic after she read that it may help protect against serious infections.

Shari and Michael Cantor both take metformin. They are both in their mid-60s and say they feel healthy and full of energy. Theresa Oberst/Michael Cantor hide caption

Shari and Michael Cantor both take metformin. They are both in their mid-60s and say they feel healthy and full of energy.

The Cantors are in their mid-60s and both say they feel healthy and have lots of energy. Both noticed improvements in their digestive systems – feeling more "regular" after they started on the drug,

Metformin costs less than a dollar a day, and depending on insurance, many people pay no out-of-pocket costs for the drug.

"I don't know if metformin increases lifespan in people, but the evidence that exists suggests that it very well might," says Steven Austad , a senior scientific advisor at the American Federation for Aging Research who studies the biology of aging.

An old drug with surprising benefits

Metformin was first used to treat diabetes in the 1950s in France. The drug is a derivative of guanidine , a compound found in Goat's Rue, an herbal medicine long used in Europe.

The FDA approved metformin for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in the U.S. in the 1990s. Since then, researchers have documented several surprises, including a reduced risk of cancer. "That was a bit of a shock," Austad says. A meta-analysis that included data from dozens of studies, found people who took metformin had a lower risk of several types of cancers , including gastrointestinal, urologic and blood cancers.

Austad also points to a British study that found a lower risk of dementia and mild cognitive decline among people with type 2 diabetes taking metformin. In addition, there's research pointing to improved cardiovascular outcomes in people who take metformin including a reduced risk of cardiovascular death .

As promising as this sounds, Austad says most of the evidence is observational, pointing only to an association between metformin and the reduced risk. The evidence stops short of proving cause and effect. Also, it's unknown if the benefits documented in people with diabetes will also reduce the risk of age-related diseases in healthy, older adults.

"That's what we need to figure out," says Steve Kritchevsky , a professor of gerontology at Wake Forest School of Medicine, who is a lead investigator for the Tame Trial.

The goal is to better understand the mechanisms and pathways by which metformin works in the body. For instance, researchers are looking at how the drug may help improve energy in the cells by stimulating autophagy, which is the process of clearing out or recycling damaged bits inside cells.

Shots - Health News

Scientists can tell how fast you're aging. now, the trick is to slow it down.

You can order a test to find out your biological age. Is it worth it?

Researchers also want to know more about how metformin can help reduce inflammation and oxidative stress, which may slow biological aging.

"When there's an excess of oxidative stress, it will damage the cell. And that accumulation of damage is essentially what aging is," Kritchevsky explains.

When the forces that are damaging cells are running faster than the forces that are repairing or replacing cells, that's aging, Kritchevsky says. And it's possible that drugs like metformin could slow this process down.

By targeting the biology of aging, the hope is to prevent or delay multiple diseases, says Dr. Nir Barzilai of Albert Einstein College of Medicine, who leads the effort to get the trial started.

The ultimate in preventative medicine

Back in 2015, Austad and a bunch of aging researchers began pushing for a clinical trial.

"A bunch of us went to the FDA to ask them to approve a trial for metformin,' Austad recalls, and the agency was receptive. "If you could help prevent multiple problems at the same time, like we think metformin may do, then that's almost the ultimate in preventative medicine," Austad says.

The aim is to enroll 3,000 people between the ages of 65 and 79 for a six-year trial. But Dr. Barzilai says it's been slow going to get it funded. "The main obstacle with funding this study is that metformin is a generic drug, so no pharmaceutical company is standing to make money," he says.

Barzilai has turned to philanthropists and foundations, and has some pledges. The National Institute on Aging, part of the National Institutes of Health, set aside about $5 million for the research, but that's not enough to pay for the study which is estimated to cost between $45 and $70 million.

The frustration over the lack of funding is that if the trial points to protective effects, millions of people could benefit. "It's something that everybody will be able to afford," Barzilai says.

Currently the FDA doesn't recognize aging as a disease to treat, but the researchers hope this would usher in a paradigm shift — from treating each age-related medical condition separately, to treating these conditions together, by targeting aging itself.

For now, metformin is only approved to treat type 2 diabetes in the U.S., but doctors can prescribe it off-label for conditions other than its approved use .

Michael and Shari Cantor's doctors were comfortable prescribing it to them, given the drug's long history of safety and the possible benefits in delaying age-related disease.

"I walk a lot, I hike, and at 65 I have a lot of energy," Michael Cantor says. I feel like the metformin helps," he says. He and Shari say they have not experienced any negative side effects.

Research shows a small percentage of people who take metformin experience GI distress that makes the drug intolerable. And, some people develop a b12 vitamin deficiency. One study found people over the age of 65 who take metformin may have a harder time building new muscle.

Millions of women are 'under-muscled.' These foods help build strength

"There's some evidence that people who exercise who are on metformin have less gain in muscle mass, says Dr. Eric Verdin , President of the Buck Institute for Research on Aging. That could be a concern for people who are under-muscled .

But Verdin says it may be possible to repurpose metformin in other ways "There are a number of companies that are exploring metformin in combination with other drugs," he says. He points to research underway to combine metformin with a drug called galantamine for the treatment of sarcopenia , which is the medical term for age-related muscle loss. Sarcopenia affects millions of older people, especially women .

The science of testing drugs to target aging is rapidly advancing, and metformin isn't the only medicine that may treat the underlying biology.

"Nobody thinks this is the be all and end all of drugs that target aging," Austad says. He says data from the clinical trial could stimulate investment by the big pharmaceutical companies in this area. "They may come up with much better drugs," he says.

Michael Cantor knows there's no guarantee with metformin. "Maybe it doesn't do what we think it does in terms of longevity, but it's certainly not going to do me any harm," he says.

Cantor's father had his first heart attack at 51. He says he wants to do all he can to prevent disease and live a healthy life, and he thinks Metformin is one tool that may help.

For now, Dr. Barzilai says the metformin clinical trial can get underway when the money comes in.

7 habits to live a healthier life, inspired by the world's longest-lived communities

This story was edited by Jane Greenhalgh

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

New research directions on disparities in obesity and type 2 diabetes

Pamela l. thornton.

1. Division of Diabetes, Endocrinology, and Metabolic Diseases; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Shiriki K. Kumanyika

2. Drexel University Dornsife School of Public Health, Philadelphia, PA.

Edward W. Gregg

3. Epidemiology and Statistics Branch, Division of Diabetes Translation, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, GA. Current Affiliation: Imperial College London, School of Public Health, Epidemiology and Biostatistics, South Kensington Campus, London, UK.

Maria R. Araneta

4. University of California San Diego Department of Family Medicine and Public Health, La Jolla, CA.

Monica L. Baskin

5. University of Alabama at Birmingham Department of Medicine Division of Preventive Medicine, Birmingham, AL.

Marshall H. Chin

6. University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago.

Carlos J. Crespo

7. Oregon Health and Science University and Portland State University joint School of Public Health, Portland, OR.

Mary de Groot

8. Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN.

David O. Garcia

9. University of Arizona Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, Department of Health Promotion Sciences, Tucson, AZ.

Debra Haire-Joshu

10. Washington University in St. Louis, School of Medicine and The Brown School, St. Louis, MO.

Michele Heisler

11. University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI.

Felicia Hill-Briggs

12. Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and Welch Center for Prevention, Epidemiology & Clinical Research, Baltimore, MD.

Joseph A. Ladapo

13. David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA.

Nangel M. Lindberg

14. Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, Portland, OR.

Spero M. Manson

15. Colorado School of Public Health, Aurora, CO.

David G. Marrero

16. University of Arizona Health Sciences, Phoenix, AZ.

Monica E. Peek

Alexandra e. shields.

17. Harvard/MGH Center on Genomics, Vulnerable Populations, and Health Disparities, Mongan Institute, Mass. General Hospital and Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Deborah F. Tate

18. University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health, Chapel Hill, NC.

Carol M. Mangione

19. David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, and UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA.

The authors of this manuscript provided substantial contributions to its conception by submitting workshop presentations and data described in the manuscript. They also participated in the major revisions of the manuscript’s intellectual content and approved the final version of the submitted manuscript. P.L.T. and S.K.K. designed the manuscript and developed the initial draft; E.W.G. codrafted the epidemiology section; A.E.S. codrafted the psychosocial/socioecological stress section; M.E.P. and M.H.C. drafted Box 1 ; and D.H.-J. drafted Box 2. All authors contributed to the revision of Table 1 .

Obesity and type 2 diabetes disproportionately impact U.S. racial and ethnic minority communities and low-income populations. Improvements in implementing efficacious interventions to reduce the incidence of type 2 diabetes are underway (i.e., National Diabetes Prevention Program), but challenges in effectively scaling-up successful interventions and reaching at-risk populations remain. In October 2017, the National Institutes of Health convened a workshop to understand how to (1) address socioeconomic and other environmental conditions that perpetuate disparities in the burden of obesity and type 2 diabetes; (2) design effective prevention and treatment strategies that are accessible, feasible, culturally relevant, and acceptable to diverse population groups; and (3) achieve sustainable health improvement approaches in communities with the greatest burden of these diseases. Common features of guiding frameworks to understand and address disparities and promote health equity were described. Promising research directions were identified in numerous areas, including study design, methodology, and core metrics; program implementation and scalability; the integration of medical care and social services; strategies to enhance patient empowerment; and understanding and addressing the impact of psychosocial stress on disease onset and progression in addition to factors that support resiliency and health.

Introduction

Obesity and type 2 diabetes are national epidemics that disproportionately impact certain populations in the United States (i.e., disparity populations). Specifically, Alaska Native, American Indian, Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic Black, 1 and Hispanic adults bear a disproportionate burden of illness related to these conditions compared to non-Hispanic Whites, 1 , 2 as do those with low socioeconomic status, living in rural areas, and identifying as LGBTQ. 3 Large efficacy trials have demonstrated that lifestyle change and/or medication (i.e., metformin) can prevent or delay progression of prediabetes to type 2 diabetes. 4

Efforts to scale-up and spread efficacious interventions are underway (e.g., National Diabetes Prevention Program), 5 but our knowledge of evidence-based strategies that specifically reduce diabetes-related disparities is limited. Innovative approaches, including strategies to improve available interventions and promote their long-term, wide-spread implementation among those at greatest risk are needed. A central challenge in improving population health is translating research conducted under the best case scenarios of well-resourced randomized controlled trials into real world scenarios, which requires addressing environmental, economic, and social factors that affect individuals’ engagement in and response to these interventions. 6

Workshop overview

The workshop entitled Enhancing Opportunities in Addressing Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Disparities, was convened at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland on October 24–25, 2017 to inform research opportunities for reducing disparities in these two conditions. The workshop was co-sponsored by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), and the NIH Office of Disease Prevention (ODP), and organized in coordination with representatives of six NIH Institutes/Offices. 2 Opening remarks by Dr. Griffin Rodgers, the NIDDK Director, and Dr. Eliseo Pérez-Stable, Director of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD), emphasized the importance of the workshop in identifying focal points for the next generation of high impact studies designed to reduce disparities in the burden of obesity and diabetes through elucidating the social contextual mechanisms of disease etiology, and facilitating lifestyle behavior changes, healthcare system interventions, and partnered community-based programs. Many questions remain, including how best to (1) address the socioeconomic and other environmental influences that have historically and currently affected the same minority populations and under-resourced and rural communities that bear a disproportionate burden of illness; (2) design prevention and treatment strategies to be accessible, feasible, culturally-relevant, and acceptable to at-risk communities; and (3) achieve sustainable health improvement strategies in communities that have the greatest burden of these chronic diseases.

More than 80 participants attended the workshop, including academic researchers and healthcare leaders with expertise in epidemiology, healthcare systems, primary care, behavioral interventions, public health, cultural adaptation of interventions, behavioral economics, health policy and administration, and implementation science. During the 2-day workshop, expert presentations facilitated rigorous discussion and helped identify promising research directions.

Epidemiologic overview

Epidemiological trends illustrate how the obesity and diabetes epidemics have grown in recent decades and the consequent adverse impact on population health. Figure 1 shows marked disparities in diabetes prevalence by race/ethnicity, education, and income. 7 Prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes is highest in non-Hispanic Black and Mexican Adults and notably higher in all three ethnic minority groups when compared with Whites. Based on Indian Health Service data, the prevalence of diagnosed diabetes among American Indians/Alaska Natives is 15%, higher than in the other ethnic minority populations. 8

Prevalence of total diabetes (diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes) in the U.S. adult population, aged ≥20 years, 2011–2016. NHW, non-Hispanic White; NHB, non-Hispanic Black; MA, Mexican American; HS, high school education; PIR, poverty income ratio. Source: Unpublished data, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 7

Figure 1 also shows the inverse gradients in diabetes prevalence with education and poverty. Figure 2 depicts striking geographic variations in diabetes and obesity prevalence. Evidence indicates that area-level poverty is the strongest single predictor of being a high-risk county. 9 The specific factors explaining why high poverty counties are at such excess risk, and what works to reduce this risk, need to be elucidated. In under-resourced communities, the importance of neighborhood context as a constraint on access to resources and options for healthy eating and active living has been well-documented, 10 , 11 , 12 yet we lack sufficient surveillance data to adequately identify modifiable risk factors in the highest risk neighborhoods.

Diagnosed Diabetes (%): Low (<9.0), Mid (9.0–13.9), High (>13.9); Obesity (%): Low (<29.1), Mid (29.1–36.0), High (>36.0). Estimates are percentages at the county-level; natural breaks were used to create categories using 2016 data.

The effects of education, income, and other indices of SES among people with or at risk for diabetes are often mediated by behavioral risk factors, including dietary patterns, levels of physical activity, and smoking. 13 For example, Siegel et al . 10 reported that, in a nationally-representative survey, higher education was associated with meeting diet-related diabetes prevention goals for intake of vegetables, whole grains, meats, and healthy oils. Lower SES has historically been associated with worse glycemic control among adults with type 2 diabetes, particularly younger adults. 14 , 15 Quality of diabetes care and preventive care practices to forestall diabetes-related complications vary according to disparities in access to care. 16 For example, even among insured populations, Latinos are less likely to receive regular care and less likely to meet HbA1c targets. 17 , 18 Lack of access to care in non-Hispanic Blacks is associated with not meeting blood pressure targets. 19

Although there have been encouraging reductions in most diabetes complications in the United States, with some improvements across all affected groups, disparities remain. They are observed most clearly in non-Hispanic Blacks, who have substantially higher rates of end-stage renal disease (ESRD), amputation, and stroke; 20 and in Hispanics and Asian Americans who have elevated ESRD complications. 21 , 22 Within these groups, men have notably higher rates of lower extremity amputation and myocardial infarction than women. The pattern of disparities in complications according to markers of social class and education does not appear to be consistent.

There have been successes in reducing diabetes-related complications through improvements in medical technology and care, cardiovascular risk factor management and glycemic control, self-management, and policy approaches (e.g., policy changes that have decreased smoking rates or improved access to health insurance and care). 23 , 24 Yet, there has been little success in reducing disparities. Reducing the disparities gap in diabetes and obesity incidence and outcomes requires tackling the social and environmental influences (e.g., neighborhood poverty, access to quality care, psychosocial stressors) known to affect disease etiology and exacerbate disparities. Diverse methods for assessing the effectiveness of interventions to reduce disparities and increase knowledge regarding the pathways and mechanisms through which social disadvantage translates into increased risk of disease are also needed.

Definitions and guiding frameworks

The concepts of health equity and social determinants of health (SDoH) were central to the workshop dialogue. According to the World Health Organization, “‘Health equity’ or ‘equity in health’ implies that ideally everyone should have a fair opportunity to attain their full health potential and that no one should be disadvantaged from achieving this potential.” 25 Improving health equity is a stated U.S. national priority and is inextricably linked to the goal of eliminating health disparities. 26 The concept of equity involves “the absence of avoidable, unfair, or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically or geographically or by other means of stratification”. 25 A large body of research demonstrates that such public health goals cannot be realized without addressing the underlying SDoH, which include environmental, economic, and social factors that significantly contribute to disparities and thus warrant much more attention. 27

Several frameworks useful for understanding and addressing health disparities and health equity issues in obesity and diabetes prevention and care were presented. These included a novel healthcare and community systems-oriented model for assessing policy and social/environmental factors influencing health equity, informed by joint analyses of health equity issues affecting ethnic minority populations in the United States and Aotearoa/New Zealand. 28 This model depicts the way government and private policies impact the healthcare system, the integration of healthcare system and social services, and the relevant SDoH, and consequently health equity (e.g., related to race/ethnicity, SES or socioeconomic deprivation)—all set within a larger context of history, culture, and values. Other notable models discussed for conceptualizing health equity issues included: the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s “Finding Answers” framework; 29 the Getting to Equity in Obesity Prevention research and action framework; 30 the Three-Axis Model of Health Inequity; 31 the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research; 32 and behavioral change models involving beliefs, knowledge, social norms, environmental factors, and self-efficacy, and intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. 33 , 34 The NIMHD Research Framework 35 along with the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) perspectives were also featured as valuable resources that illustrate funding agencies’ strategic priorities.

A theme that emerged from these presentations is that, despite sharing common features among health equity frameworks, there is value in having different frameworks for guidance within the policy, practice, and community contexts relevant to prevention and treatment. Some frameworks are designed to explain causes of disparities while others are designed to show where and how solutions to disparities could and should focus. Most frameworks—including those that focus primarily on healthcare delivery systems—acknowledge the importance of community contexts as key health determinants. Other common features among the frameworks were:

- Prominent recognition of the fundamental roles of “race,” ethnicity, SES, gender, and geography in determining health.

- Emphasis on the need to tailor conceptual frameworks according to different health domains and contextual levels.

For example, with respect to the latter, causes rooted in inequitable social structures or inadequate social protections suggest high-level policy solutions, whereas causes related to risky behaviors may point to policy-oriented and individually or family-oriented interventions and the proximal contextual factors influencing these behaviors. Causes of inequities rooted in healthcare system processes could trigger solutions involving regulatory or financing agencies, institutions involved in provider training, and system-level policy mandates addressing ongoing provider training and quality improvement. Regardless, virtually all frameworks emphasize the need for mutually reinforcing interventions at multiple levels, through socioecological models using the traditional concentric circles or other formats, to represent interrelationships among individual, community, neighborhood and/or healthcare- and policy-level influences.

Bridging interventions in healthcare settings to broader community contexts

Interventions in healthcare settings to address obesity and type 2 diabetes-related disparities involve complex considerations at the patient-, provider-, healthcare system and policy-levels. Novel implementation approaches that take account of individuals’ social contexts are necessary for full and sustained achievement of healthy lifestyle behaviors. Although a clinical perspective is considered foundational for diabetes treatment, the traditional clinical context is too narrow to accommodate broader influences on health disparities.

Perspectives and pragmatic lessons