- Search by keyword

- Search by citation

Page 1 of 12

Cx43 hemichannels and panx1 channels contribute to ethanol-induced astrocyte dysfunction and damage

Alcohol, a widely abused drug, significantly diminishes life quality, causing chronic diseases and psychiatric issues, with severe health, societal, and economic repercussions. Previously, we demonstrated that...

- View Full Text

Galectins in epithelial-mesenchymal transition: roles and mechanisms contributing to tissue repair, fibrosis and cancer metastasis

Galectins are soluble glycan-binding proteins that interact with a wide range of glycoproteins and glycolipids and modulate a broad spectrum of physiological and pathological processes. The expression and subc...

Glutaminolysis regulates endometrial fibrosis in intrauterine adhesion via modulating mitochondrial function

Endometrial fibrosis, a significant characteristic of intrauterine adhesion (IUA), is caused by the excessive differentiation and activation of endometrial stromal cells (ESCs). Glutaminolysis is the metabolic...

The long-chain flavodoxin FldX1 improves the biodegradation of 4-hydroxyphenylacetate and 3-hydroxyphenylacetate and counteracts the oxidative stress associated to aromatic catabolism in Paraburkholderia xenovorans

Bacterial aromatic degradation may cause oxidative stress. The long-chain flavodoxin FldX1 of Paraburkholderia xenovorans LB400 counteracts reactive oxygen species (ROS). The aim of this study was to evaluate the...

MicroRNA-148b secreted by bovine oviductal extracellular vesicles enhance embryo quality through BPM/TGF-beta pathway

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) and their cargoes, including MicroRNAs (miRNAs) play a crucial role in cell-to-cell communication. We previously demonstrated the upregulation of bta-mir-148b in EVs from oviductal...

YME1L-mediated mitophagy protects renal tubular cells against cellular senescence under diabetic conditions

The senescence of renal tubular epithelial cells (RTECs) is crucial in the progression of diabetic kidney disease (DKD). Accumulating evidence suggests a close association between insufficient mitophagy and RT...

Effects of latroeggtoxin-VI on dopamine and α-synuclein in PC12 cells and the implications for Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is characterized by death of dopaminergic neurons leading to dopamine deficiency, excessive α-synuclein facilitating Lewy body formation, etc. Latroeggtoxin-VI (LETX-VI), a proteinaceo...

Glial-restricted progenitor cells: a cure for diseased brain?

The central nervous system (CNS) is home to neuronal and glial cells. Traditionally, glia was disregarded as just the structural support across the brain and spinal cord, in striking contrast to neurons, alway...

Carbapenem-resistant hypervirulent ST23 Klebsiella pneumoniae with a highly transmissible dual-carbapenemase plasmid in Chile

The convergence of hypervirulence and carbapenem resistance in the bacterial pathogen Klebsiella pneumoniae represents a critical global health concern. Hypervirulent K. pneumoniae (hvKp) strains, frequently from...

Endometrial mesenchymal stromal/stem cells improve regeneration of injured endometrium in mice

The monthly regeneration of human endometrial tissue is maintained by the presence of human endometrial mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (eMSC), a cell population co-expressing the perivascular markers CD140b an...

Embryo development is impaired by sperm mitochondrial-derived ROS

Basal energetic metabolism in sperm, particularly oxidative phosphorylation, is known to condition not only their oocyte fertilising ability, but also the subsequent embryo development. While the molecular pat...

Fibroblasts inhibit osteogenesis by regulating nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of YAP in mesenchymal stem cells and secreting DKK1

Fibrous scars frequently form at the sites of bone nonunion when attempts to repair bone fractures have failed. However, the detailed mechanism by which fibroblasts, which are the main components of fibrous sc...

MSC-derived exosomes protect auditory hair cells from neomycin-induced damage via autophagy regulation

Sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) poses a major threat to both physical and mental health; however, there is still a lack of effective drugs to treat the disease. Recently, novel biological therapies, such as ...

Alpha-synuclein dynamics bridge Type-I Interferon response and SARS-CoV-2 replication in peripheral cells

Increasing evidence suggests a double-faceted role of alpha-synuclein (α-syn) following infection by a variety of viruses, including SARS-CoV-2. Although α-syn accumulation is known to contribute to cell toxic...

Lactadherin immunoblockade in small extracellular vesicles inhibits sEV-mediated increase of pro-metastatic capacities

Tumor-derived small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) can promote tumorigenic and metastatic capacities in less aggressive recipient cells mainly through the biomolecules in their cargo. However, despite recent ad...

Integration of ATAC-seq and RNA-seq identifies MX1-mediated AP-1 transcriptional regulation as a therapeutic target for Down syndrome

Growing evidence has suggested that Type I Interferon (I-IFN) plays a potential role in the pathogenesis of Down Syndrome (DS). This work investigates the underlying function of MX1, an effector gene of I-IFN,...

The novel roles of YULINK in the migration, proliferation and glycolysis of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells: implications for pulmonary arterial hypertension

Abnormal remodeling of the pulmonary vasculature, characterized by the proliferation and migration of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) along with dysregulated glycolysis, is a pathognomonic feat...

Electroacupuncture promotes neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus and improves pattern separation in an early Alzheimer's disease mouse model

Impaired pattern separation occurs in the early stage of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG) neurogenesis participates in pattern separation. Here, we investigated whether spatial memo...

Role of SYVN1 in the control of airway remodeling in asthma protection by promoting SIRT2 ubiquitination and degradation

Asthma is a heterogenous disease that characterized by airway remodeling. SYVN1 (Synoviolin 1) acts as an E3 ligase to mediate the suppression of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress through ubiquitination and de...

Advances towards the use of gastrointestinal tumor patient-derived organoids as a therapeutic decision-making tool

In December 2022 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) removed the requirement that drugs in development must undergo animal testing before clinical evaluation, a declaration that now demands the establish...

Melatonin alleviates pyroptosis by regulating the SIRT3/FOXO3α/ROS axis and interacting with apoptosis in Atherosclerosis progression

Atherosclerosis (AS), a significant contributor to cardiovascular disease (CVD), is steadily rising with the aging of the global population. Pyroptosis and apoptosis, both caspase-mediated cell death mechanism...

Prenatal ethanol exposure and changes in fetal neuroendocrine metabolic programming

Prenatal ethanol exposure (PEE) (mainly through maternal alcohol consumption) has become widespread. However, studies suggest that it can cause intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) and multi-organ developmen...

Autologous non-invasively derived stem cells mitochondria transfer shows therapeutic advantages in human embryo quality rescue

The decline in the quantity and quality of mitochondria are closely associated with infertility, particularly in advanced maternal age. Transferring autologous mitochondria into the oocytes of infertile female...

Development of synthetic modulator enabling long-term propagation and neurogenesis of human embryonic stem cell-derived neural progenitor cells

Neural progenitor cells (NPCs) are essential for in vitro drug screening and cell-based therapies for brain-related disorders, necessitating well-defined and reproducible culture systems. Current strategies em...

Heat-responsive microRNAs participate in regulating the pollen fertility stability of CMS-D2 restorer line under high-temperature stress

Anther development and pollen fertility of cytoplasmic male sterility (CMS) conditioned by Gossypium harknessii cytoplasm (CMS-D2) restorer lines are susceptible to continuous high-temperature (HT) stress in sum...

Chemogenetic inhibition of NTS astrocytes normalizes cardiac autonomic control and ameliorate hypertension during chronic intermittent hypoxia

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is characterized by recurrent episodes of chronic intermittent hypoxia (CIH), which has been linked to the development of sympathoexcitation and hypertension. Furthermore, it has ...

SARS-CoV-2 spike protein S1 activates Cx43 hemichannels and disturbs intracellular Ca 2+ dynamics

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causes the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). An aspect of high uncertainty is whether the SARS-CoV-2 per se or the systemic inflammation ...

The effect of zofenopril on the cardiovascular system of spontaneously hypertensive rats treated with the ACE2 inhibitor MLN-4760

Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) plays a crucial role in the infection cycle of SARS-CoV-2 responsible for formation of COVID-19 pandemic. In the cardiovascular system, the virus enters the cells by bind...

Two murine models of sepsis: immunopathological differences between the sexes—possible role of TGFβ1 in female resistance to endotoxemia

Endotoxic shock (ExSh) and cecal ligature and puncture (CLP) are models that induce sepsis. In this work, we investigated early immunologic and histopathologic changes induced by ExSh or CLP models in female a...

An intracellular, non-oxidative factor activates in vitro chromatin fragmentation in pig sperm

In vitro incubation of epididymal and vas deferens sperm with Mn 2+ induces Sperm Chromatin Fragmentation (SCF), a mechanism that causes double-stranded breaks in toroid-linker regions (TLRs). Whether this mechani...

Focal ischemic stroke modifies microglia-derived exosomal miRNAs: potential role of mir-212-5p in neuronal protection and functional recovery

Ischemic stroke is a severe type of stroke with high disability and mortality rates. In recent years, microglial exosome-derived miRNAs have been shown to be promising candidates for the treatment of ischemic ...

S -Nitrosylation in endothelial cells contributes to tumor cell adhesion and extravasation during breast cancer metastasis

Nitric oxide is produced by different nitric oxide synthases isoforms. NO activates two signaling pathways, one dependent on soluble guanylate cyclase and protein kinase G, and other where NO post-translationa...

Identifying pyroptosis- and inflammation-related genes in intracranial aneurysms based on bioinformatics analysis

Intracranial aneurysm (IA) is the most common cerebrovascular disease, and subarachnoid hemorrhage caused by its rupture can seriously impede nerve function. Pyroptosis is an inflammatory mode of cell death wh...

Drosophila Atlastin regulates synaptic vesicle mobilization independent of bone morphogenetic protein signaling

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) contacts endosomes in all parts of a motor neuron, including the axon and presynaptic terminal, to move structural proteins, proteins that send signals, and lipids over long dist...

Mucin1 induced trophoblast dysfunction in gestational diabetes mellitus via Wnt/β-catenin pathway

To elucidate the role of Mucin1 (MUC1) in the trophoblast function (glucose uptake and apoptosis) of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) women through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (hUC-MSCs) alleviate paclitaxel-induced spermatogenesis defects and maintain male fertility

Chemotherapeutic drugs can cause reproductive damage by affecting sperm quality and other aspects of male fertility. Stem cells are thought to alleviate the damage caused by chemotherapy drugs and to play role...

Exploring the Neandertal legacy of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma risk in Eurasians

The genomes of present-day non-Africans are composed of 1–3% of Neandertal-derived DNA as a consequence of admixture events between Neandertals and anatomically modern humans about 50–60 thousand years ago. Ne...

Identification and analysis of key hypoxia- and immune-related genes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), an autosomal dominant genetic disease, is the main cause of sudden death in adolescents and athletes globally. Hypoxia and immune factors have been revealed to be related to ...

How do prolonged anchorage-free lifetimes strengthen non-small-cell lung cancer cells to evade anoikis? – A link with altered cellular metabolomics

Malignant cells adopt anoikis resistance to survive anchorage-free stresses and initiate cancer metastasis. It is still unknown how varying periods of anchorage loss contribute to anoikis resistance, cell migr...

Single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with wine fermentation and adaptation to nitrogen limitation in wild and domesticated yeast strains

For more than 20 years, Saccharomyces cerevisiae has served as a model organism for genetic studies and molecular biology, as well as a platform for biotechnology (e.g., wine production). One of the important eco...

Investigating the dark-side of the genome: a barrier to human disease variant discovery?

The human genome contains regions that cannot be adequately assembled or aligned using next generation short-read sequencing technologies. More than 2500 genes are known contain such ‘dark’ regions. In this st...

Hyperbaric oxygen treatment increases intestinal stem cell proliferation through the mTORC1/S6K1 signaling pathway in Mus musculus

Hyperbaric oxygen treatment (HBOT) has been reported to modulate the proliferation of neural and mesenchymal stem cell populations, but the molecular mechanisms underlying these effects are not completely unde...

Polar microalgae extracts protect human HaCaT keratinocytes from damaging stimuli and ameliorate psoriatic skin inflammation in mice

Polar microalgae contain unique compounds that enable them to adapt to extreme environments. As the skin barrier is our first line of defense against external threats, polar microalgae extracts may possess res...

Correction: Utility of melatonin in mitigating ionizing radiation‑induced testis injury through synergistic interdependence of its biological properties

The original article was published in Biological Research 2022 55 :33

Beyond energy provider: multifunction of lipid droplets in embryonic development

Since the discovery, lipid droplets (LDs) have been recognized to be sites of cellular energy reserves, providing energy when necessary to sustain cellular life activities. Many studies have reported large num...

Retraction Note: Tridax procumbens flavonoids: a prospective bioactive compound increased osteoblast differentiation and trabecular bone formation

Electroacupuncture protective effects after cerebral ischemia are mediated through mir-219a inhibition.

Electroacupuncture (EA) is a complementary and alternative therapy which has shown protective effects on vascular cognitive impairment (VCI). However, the underlying mechanisms are not entirely understood.

Topsoil and subsoil bacterial community assemblies across different drainage conditions in a mountain environment

High mountainous environments are of particular interest as they play an essential role for life and human societies, while being environments which are highly vulnerable to climate change and land use intensi...

Functional defects in hiPSCs-derived cardiomyocytes from patients with a PLEKHM2-mutation associated with dilated cardiomyopathy and left ventricular non-compaction

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a primary myocardial disease, leading to heart failure and excessive risk of sudden cardiac death with rather poorly understood pathophysiology. In 2015, Parvari's group ident...

Human VDAC pseudogenes: an emerging role for VDAC1P8 pseudogene in acute myeloid leukemia

Voltage-dependent anion selective channels (VDACs) are the most abundant mitochondrial outer membrane proteins, encoded in mammals by three genes, VDAC1 , 2 and 3 , mostly ubiquitously expressed. As 'mitochondrial ...

- Editorial Board

- Manuscript editing services

- Instructions for Editors

- Sign up for article alerts and news from this journal

- Follow us on Twitter

- Follow us on Facebook

- ISSN: 0717-6287 (electronic)

Biological Research

ISSN: 0717-6287

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Library Search

- View Library Account

- The Claremont Colleges Library

- Research Guides

- Articles and Primary Literature

- Get Started

Articles and Primary Literature in Biology

Databases for finding articles.

- Secondary Sources

- Write and Cite in the Sciences

- Sub-discipline Resources

- Chemical and Lab Safety

In the sciences, a primary source describes original research, while a secondary source analyzes or comments on a primary source or sources. For example, a research article is primary literature because it describes an original experiment and its results, while a review article is secondary literature because it collates multiple research articles to describe the current state of the field.

Examples of primary sources:

- Research articles

- Theses and dissertations

- Conference proceedings

- Patents

- Unrefined data sets

Examples of secondary sources:

- Review articles

- Data compilations

The databases below can help you find primary literature in the sciences. While searching, you can narrow your results to primary literature by using filters on the left of the page.

- Web of Science This link opens in a new window A large interdisciplinary database with a strong collection in the sciences. Filter for primary literature by selecting Article under Document Type on the left of the page. more... less... Easily explore an article bibliography, as well as sources that have cited the article since its publication, via the Citation Network feature. Create a free personal account to keep a comprehensive search history, create search alerts and citation alerts. Additional features related to author and journal profiles are available. Language: English, Russian, French, German, Chinese, Spanish, Japanese, Portuguese, etc. Keywords: Social Science Citation Index Science Citation Index Arts and Humanities Citation Index Conference Proceedings Citation Index Emerging Sources Citation Index WoS Knowledge

- PubMed This link opens in a new window A massive biomedical database run by the NIH, with articles stretching back to the 1950s. Filter primary literature by selecting Clinical Trial under Article Type on the top left of the page. more... less... Includes advanced search tools such as Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and the Clinical Queries feature. Personalized MyNCBI account features, such as email alerts, are only available by leaving the Library's instance of PubMed and accessing the resource through the open web site (pubmed.gov). Language: English Keywords: Pub Med

- USDA National Agricultural Library This link opens in a new window Why search here? Good for indexed citations from AGRICOLA, PubAg, and the NAL Digital Collections (NALDC) on agriculture topics, food and human nutrition, forestry, aquaculture and fisheries, animal and veterinary sciences. Content type: Abstracts of scholarly articles, book chapters, theses, patents, technical reports. Coverage dates: 1970 - present more... less... Language: English Keywords: Pub Ag U.S. US Department

- << Previous: Get Started

- Next: Secondary Sources >>

- : Feb 19, 2024 3:26 PM

- URL: https://libguides.libraries.claremont.edu/biology

Change Password

Your password must have 8 characters or more and contain 3 of the following:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

- Sign in / Register

Request Username

Can't sign in? Forgot your username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

Literature Reviews, Theoretical Frameworks, and Conceptual Frameworks: An Introduction for New Biology Education Researchers

- Julie A. Luft

- Sophia Jeong

- Robert Idsardi

- Grant Gardner

Department of Mathematics, Social Studies, and Science Education, Mary Frances Early College of Education, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602-7124

Search for more papers by this author

*Address correspondence to: Sophia Jeong ( E-mail Address: [email protected] ).

Department of Teaching & Learning, College of Education & Human Ecology, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210

Department of Biology, Eastern Washington University, Cheney, WA 99004

Department of Biology, Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN 37132

To frame their work, biology education researchers need to consider the role of literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks as critical elements of the research and writing process. However, these elements can be confusing for scholars new to education research. This Research Methods article is designed to provide an overview of each of these elements and delineate the purpose of each in the educational research process. We describe what biology education researchers should consider as they conduct literature reviews, identify theoretical frameworks, and construct conceptual frameworks. Clarifying these different components of educational research studies can be helpful to new biology education researchers and the biology education research community at large in situating their work in the broader scholarly literature.

INTRODUCTION

Discipline-based education research (DBER) involves the purposeful and situated study of teaching and learning in specific disciplinary areas ( Singer et al. , 2012 ). Studies in DBER are guided by research questions that reflect disciplines’ priorities and worldviews. Researchers can use quantitative data, qualitative data, or both to answer these research questions through a variety of methodological traditions. Across all methodologies, there are different methods associated with planning and conducting educational research studies that include the use of surveys, interviews, observations, artifacts, or instruments. Ensuring the coherence of these elements to the discipline’s perspective also involves situating the work in the broader scholarly literature. The tools for doing this include literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks. However, the purpose and function of each of these elements is often confusing to new education researchers. The goal of this article is to introduce new biology education researchers to these three important elements important in DBER scholarship and the broader educational literature.

The first element we discuss is a review of research (literature reviews), which highlights the need for a specific research question, study problem, or topic of investigation. Literature reviews situate the relevance of the study within a topic and a field. The process may seem familiar to science researchers entering DBER fields, but new researchers may still struggle in conducting the review. Booth et al. (2016b) highlight some of the challenges novice education researchers face when conducting a review of literature. They point out that novice researchers struggle in deciding how to focus the review, determining the scope of articles needed in the review, and knowing how to be critical of the articles in the review. Overcoming these challenges (and others) can help novice researchers construct a sound literature review that can inform the design of the study and help ensure the work makes a contribution to the field.

The second and third highlighted elements are theoretical and conceptual frameworks. These guide biology education research (BER) studies, and may be less familiar to science researchers. These elements are important in shaping the construction of new knowledge. Theoretical frameworks offer a way to explain and interpret the studied phenomenon, while conceptual frameworks clarify assumptions about the studied phenomenon. Despite the importance of these constructs in educational research, biology educational researchers have noted the limited use of theoretical or conceptual frameworks in published work ( DeHaan, 2011 ; Dirks, 2011 ; Lo et al. , 2019 ). In reviewing articles published in CBE—Life Sciences Education ( LSE ) between 2015 and 2019, we found that fewer than 25% of the research articles had a theoretical or conceptual framework (see the Supplemental Information), and at times there was an inconsistent use of theoretical and conceptual frameworks. Clearly, these frameworks are challenging for published biology education researchers, which suggests the importance of providing some initial guidance to new biology education researchers.

Fortunately, educational researchers have increased their explicit use of these frameworks over time, and this is influencing educational research in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. For instance, a quick search for theoretical or conceptual frameworks in the abstracts of articles in Educational Research Complete (a common database for educational research) in STEM fields demonstrates a dramatic change over the last 20 years: from only 778 articles published between 2000 and 2010 to 5703 articles published between 2010 and 2020, a more than sevenfold increase. Greater recognition of the importance of these frameworks is contributing to DBER authors being more explicit about such frameworks in their studies.

Collectively, literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks work to guide methodological decisions and the elucidation of important findings. Each offers a different perspective on the problem of study and is an essential element in all forms of educational research. As new researchers seek to learn about these elements, they will find different resources, a variety of perspectives, and many suggestions about the construction and use of these elements. The wide range of available information can overwhelm the new researcher who just wants to learn the distinction between these elements or how to craft them adequately.

Our goal in writing this paper is not to offer specific advice about how to write these sections in scholarly work. Instead, we wanted to introduce these elements to those who are new to BER and who are interested in better distinguishing one from the other. In this paper, we share the purpose of each element in BER scholarship, along with important points on its construction. We also provide references for additional resources that may be beneficial to better understanding each element. Table 1 summarizes the key distinctions among these elements.

This article is written for the new biology education researcher who is just learning about these different elements or for scientists looking to become more involved in BER. It is a result of our own work as science education and biology education researchers, whether as graduate students and postdoctoral scholars or newly hired and established faculty members. This is the article we wish had been available as we started to learn about these elements or discussed them with new educational researchers in biology.

LITERATURE REVIEWS

Purpose of a literature review.

A literature review is foundational to any research study in education or science. In education, a well-conceptualized and well-executed review provides a summary of the research that has already been done on a specific topic and identifies questions that remain to be answered, thus illustrating the current research project’s potential contribution to the field and the reasoning behind the methodological approach selected for the study ( Maxwell, 2012 ). BER is an evolving disciplinary area that is redefining areas of conceptual emphasis as well as orientations toward teaching and learning (e.g., Labov et al. , 2010 ; American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2011 ; Nehm, 2019 ). As a result, building comprehensive, critical, purposeful, and concise literature reviews can be a challenge for new biology education researchers.

Building Literature Reviews

There are different ways to approach and construct a literature review. Booth et al. (2016a) provide an overview that includes, for example, scoping reviews, which are focused only on notable studies and use a basic method of analysis, and integrative reviews, which are the result of exhaustive literature searches across different genres. Underlying each of these different review processes are attention to the s earch process, a ppraisa l of articles, s ynthesis of the literature, and a nalysis: SALSA ( Booth et al. , 2016a ). This useful acronym can help the researcher focus on the process while building a specific type of review.

However, new educational researchers often have questions about literature reviews that are foundational to SALSA or other approaches. Common questions concern determining which literature pertains to the topic of study or the role of the literature review in the design of the study. This section addresses such questions broadly while providing general guidance for writing a narrative literature review that evaluates the most pertinent studies.

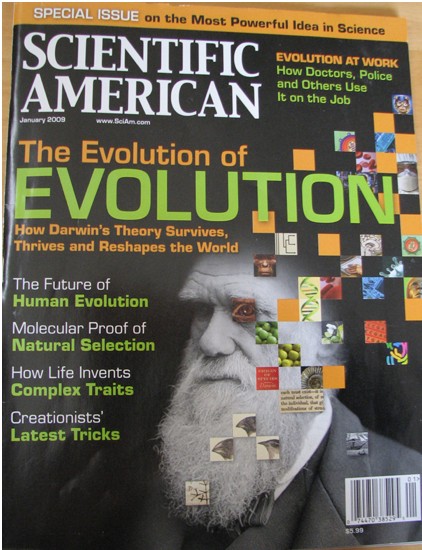

The literature review process should begin before the research is conducted. As Boote and Beile (2005 , p. 3) suggested, researchers should be “scholars before researchers.” They point out that having a good working knowledge of the proposed topic helps illuminate avenues of study. Some subject areas have a deep body of work to read and reflect upon, providing a strong foundation for developing the research question(s). For instance, the teaching and learning of evolution is an area of long-standing interest in the BER community, generating many studies (e.g., Perry et al. , 2008 ; Barnes and Brownell, 2016 ) and reviews of research (e.g., Sickel and Friedrichsen, 2013 ; Ziadie and Andrews, 2018 ). Emerging areas of BER include the affective domain, issues of transfer, and metacognition ( Singer et al. , 2012 ). Many studies in these areas are transdisciplinary and not always specific to biology education (e.g., Rodrigo-Peiris et al. , 2018 ; Kolpikova et al. , 2019 ). These newer areas may require reading outside BER; fortunately, summaries of some of these topics can be found in the Current Insights section of the LSE website.

In focusing on a specific problem within a broader research strand, a new researcher will likely need to examine research outside BER. Depending upon the area of study, the expanded reading list might involve a mix of BER, DBER, and educational research studies. Determining the scope of the reading is not always straightforward. A simple way to focus one’s reading is to create a “summary phrase” or “research nugget,” which is a very brief descriptive statement about the study. It should focus on the essence of the study, for example, “first-year nonmajor students’ understanding of evolution,” “metacognitive prompts to enhance learning during biochemistry,” or “instructors’ inquiry-based instructional practices after professional development programming.” This type of phrase should help a new researcher identify two or more areas to review that pertain to the study. Focusing on recent research in the last 5 years is a good first step. Additional studies can be identified by reading relevant works referenced in those articles. It is also important to read seminal studies that are more than 5 years old. Reading a range of studies should give the researcher the necessary command of the subject in order to suggest a research question.

Given that the research question(s) arise from the literature review, the review should also substantiate the selected methodological approach. The review and research question(s) guide the researcher in determining how to collect and analyze data. Often the methodological approach used in a study is selected to contribute knowledge that expands upon what has been published previously about the topic (see Institute of Education Sciences and National Science Foundation, 2013 ). An emerging topic of study may need an exploratory approach that allows for a description of the phenomenon and development of a potential theory. This could, but not necessarily, require a methodological approach that uses interviews, observations, surveys, or other instruments. An extensively studied topic may call for the additional understanding of specific factors or variables; this type of study would be well suited to a verification or a causal research design. These could entail a methodological approach that uses valid and reliable instruments, observations, or interviews to determine an effect in the studied event. In either of these examples, the researcher(s) may use a qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods methodological approach.

Even with a good research question, there is still more reading to be done. The complexity and focus of the research question dictates the depth and breadth of the literature to be examined. Questions that connect multiple topics can require broad literature reviews. For instance, a study that explores the impact of a biology faculty learning community on the inquiry instruction of faculty could have the following review areas: learning communities among biology faculty, inquiry instruction among biology faculty, and inquiry instruction among biology faculty as a result of professional learning. Biology education researchers need to consider whether their literature review requires studies from different disciplines within or outside DBER. For the example given, it would be fruitful to look at research focused on learning communities with faculty in STEM fields or in general education fields that result in instructional change. It is important not to be too narrow or too broad when reading. When the conclusions of articles start to sound similar or no new insights are gained, the researcher likely has a good foundation for a literature review. This level of reading should allow the researcher to demonstrate a mastery in understanding the researched topic, explain the suitability of the proposed research approach, and point to the need for the refined research question(s).

The literature review should include the researcher’s evaluation and critique of the selected studies. A researcher may have a large collection of studies, but not all of the studies will follow standards important in the reporting of empirical work in the social sciences. The American Educational Research Association ( Duran et al. , 2006 ), for example, offers a general discussion about standards for such work: an adequate review of research informing the study, the existence of sound and appropriate data collection and analysis methods, and appropriate conclusions that do not overstep or underexplore the analyzed data. The Institute of Education Sciences and National Science Foundation (2013) also offer Common Guidelines for Education Research and Development that can be used to evaluate collected studies.

Because not all journals adhere to such standards, it is important that a researcher review each study to determine the quality of published research, per the guidelines suggested earlier. In some instances, the research may be fatally flawed. Examples of such flaws include data that do not pertain to the question, a lack of discussion about the data collection, poorly constructed instruments, or an inadequate analysis. These types of errors result in studies that are incomplete, error-laden, or inaccurate and should be excluded from the review. Most studies have limitations, and the author(s) often make them explicit. For instance, there may be an instructor effect, recognized bias in the analysis, or issues with the sample population. Limitations are usually addressed by the research team in some way to ensure a sound and acceptable research process. Occasionally, the limitations associated with the study can be significant and not addressed adequately, which leaves a consequential decision in the hands of the researcher. Providing critiques of studies in the literature review process gives the reader confidence that the researcher has carefully examined relevant work in preparation for the study and, ultimately, the manuscript.

A solid literature review clearly anchors the proposed study in the field and connects the research question(s), the methodological approach, and the discussion. Reviewing extant research leads to research questions that will contribute to what is known in the field. By summarizing what is known, the literature review points to what needs to be known, which in turn guides decisions about methodology. Finally, notable findings of the new study are discussed in reference to those described in the literature review.

Within published BER studies, literature reviews can be placed in different locations in an article. When included in the introductory section of the study, the first few paragraphs of the manuscript set the stage, with the literature review following the opening paragraphs. Cooper et al. (2019) illustrate this approach in their study of course-based undergraduate research experiences (CUREs). An introduction discussing the potential of CURES is followed by an analysis of the existing literature relevant to the design of CUREs that allows for novel student discoveries. Within this review, the authors point out contradictory findings among research on novel student discoveries. This clarifies the need for their study, which is described and highlighted through specific research aims.

A literature reviews can also make up a separate section in a paper. For example, the introduction to Todd et al. (2019) illustrates the need for their research topic by highlighting the potential of learning progressions (LPs) and suggesting that LPs may help mitigate learning loss in genetics. At the end of the introduction, the authors state their specific research questions. The review of literature following this opening section comprises two subsections. One focuses on learning loss in general and examines a variety of studies and meta-analyses from the disciplines of medical education, mathematics, and reading. The second section focuses specifically on LPs in genetics and highlights student learning in the midst of LPs. These separate reviews provide insights into the stated research question.

Suggestions and Advice

A well-conceptualized, comprehensive, and critical literature review reveals the understanding of the topic that the researcher brings to the study. Literature reviews should not be so big that there is no clear area of focus; nor should they be so narrow that no real research question arises. The task for a researcher is to craft an efficient literature review that offers a critical analysis of published work, articulates the need for the study, guides the methodological approach to the topic of study, and provides an adequate foundation for the discussion of the findings.

In our own writing of literature reviews, there are often many drafts. An early draft may seem well suited to the study because the need for and approach to the study are well described. However, as the results of the study are analyzed and findings begin to emerge, the existing literature review may be inadequate and need revision. The need for an expanded discussion about the research area can result in the inclusion of new studies that support the explanation of a potential finding. The literature review may also prove to be too broad. Refocusing on a specific area allows for more contemplation of a finding.

Booth, A., Sutton, A., & Papaioannou, D. (2016a). Systemic approaches to a successful literature review (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. This book addresses different types of literature reviews and offers important suggestions pertaining to defining the scope of the literature review and assessing extant studies.

Booth, W. C., Colomb, G. G., Williams, J. M., Bizup, J., & Fitzgerald, W. T. (2016b). The craft of research (4th ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. This book can help the novice consider how to make the case for an area of study. While this book is not specifically about literature reviews, it offers suggestions about making the case for your study.

Galvan, J. L., & Galvan, M. C. (2017). Writing literature reviews: A guide for students of the social and behavioral sciences (7th ed.). Routledge. This book offers guidance on writing different types of literature reviews. For the novice researcher, there are useful suggestions for creating coherent literature reviews.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS

Purpose of theoretical frameworks.

As new education researchers may be less familiar with theoretical frameworks than with literature reviews, this discussion begins with an analogy. Envision a biologist, chemist, and physicist examining together the dramatic effect of a fog tsunami over the ocean. A biologist gazing at this phenomenon may be concerned with the effect of fog on various species. A chemist may be interested in the chemical composition of the fog as water vapor condenses around bits of salt. A physicist may be focused on the refraction of light to make fog appear to be “sitting” above the ocean. While observing the same “objective event,” the scientists are operating under different theoretical frameworks that provide a particular perspective or “lens” for the interpretation of the phenomenon. Each of these scientists brings specialized knowledge, experiences, and values to this phenomenon, and these influence the interpretation of the phenomenon. The scientists’ theoretical frameworks influence how they design and carry out their studies and interpret their data.

Within an educational study, a theoretical framework helps to explain a phenomenon through a particular lens and challenges and extends existing knowledge within the limitations of that lens. Theoretical frameworks are explicitly stated by an educational researcher in the paper’s framework, theory, or relevant literature section. The framework shapes the types of questions asked, guides the method by which data are collected and analyzed, and informs the discussion of the results of the study. It also reveals the researcher’s subjectivities, for example, values, social experience, and viewpoint ( Allen, 2017 ). It is essential that a novice researcher learn to explicitly state a theoretical framework, because all research questions are being asked from the researcher’s implicit or explicit assumptions of a phenomenon of interest ( Schwandt, 2000 ).

Selecting Theoretical Frameworks

Theoretical frameworks are one of the most contemplated elements in our work in educational research. In this section, we share three important considerations for new scholars selecting a theoretical framework.

The first step in identifying a theoretical framework involves reflecting on the phenomenon within the study and the assumptions aligned with the phenomenon. The phenomenon involves the studied event. There are many possibilities, for example, student learning, instructional approach, or group organization. A researcher holds assumptions about how the phenomenon will be effected, influenced, changed, or portrayed. It is ultimately the researcher’s assumption(s) about the phenomenon that aligns with a theoretical framework. An example can help illustrate how a researcher’s reflection on the phenomenon and acknowledgment of assumptions can result in the identification of a theoretical framework.

In our example, a biology education researcher may be interested in exploring how students’ learning of difficult biological concepts can be supported by the interactions of group members. The phenomenon of interest is the interactions among the peers, and the researcher assumes that more knowledgeable students are important in supporting the learning of the group. As a result, the researcher may draw on Vygotsky’s (1978) sociocultural theory of learning and development that is focused on the phenomenon of student learning in a social setting. This theory posits the critical nature of interactions among students and between students and teachers in the process of building knowledge. A researcher drawing upon this framework holds the assumption that learning is a dynamic social process involving questions and explanations among students in the classroom and that more knowledgeable peers play an important part in the process of building conceptual knowledge.

It is important to state at this point that there are many different theoretical frameworks. Some frameworks focus on learning and knowing, while other theoretical frameworks focus on equity, empowerment, or discourse. Some frameworks are well articulated, and others are still being refined. For a new researcher, it can be challenging to find a theoretical framework. Two of the best ways to look for theoretical frameworks is through published works that highlight different frameworks.

When a theoretical framework is selected, it should clearly connect to all parts of the study. The framework should augment the study by adding a perspective that provides greater insights into the phenomenon. It should clearly align with the studies described in the literature review. For instance, a framework focused on learning would correspond to research that reported different learning outcomes for similar studies. The methods for data collection and analysis should also correspond to the framework. For instance, a study about instructional interventions could use a theoretical framework concerned with learning and could collect data about the effect of the intervention on what is learned. When the data are analyzed, the theoretical framework should provide added meaning to the findings, and the findings should align with the theoretical framework.

A study by Jensen and Lawson (2011) provides an example of how a theoretical framework connects different parts of the study. They compared undergraduate biology students in heterogeneous and homogeneous groups over the course of a semester. Jensen and Lawson (2011) assumed that learning involved collaboration and more knowledgeable peers, which made Vygotsky’s (1978) theory a good fit for their study. They predicted that students in heterogeneous groups would experience greater improvement in their reasoning abilities and science achievements with much of the learning guided by the more knowledgeable peers.

In the enactment of the study, they collected data about the instruction in traditional and inquiry-oriented classes, while the students worked in homogeneous or heterogeneous groups. To determine the effect of working in groups, the authors also measured students’ reasoning abilities and achievement. Each data-collection and analysis decision connected to understanding the influence of collaborative work.

Their findings highlighted aspects of Vygotsky’s (1978) theory of learning. One finding, for instance, posited that inquiry instruction, as a whole, resulted in reasoning and achievement gains. This links to Vygotsky (1978) , because inquiry instruction involves interactions among group members. A more nuanced finding was that group composition had a conditional effect. Heterogeneous groups performed better with more traditional and didactic instruction, regardless of the reasoning ability of the group members. Homogeneous groups worked better during interaction-rich activities for students with low reasoning ability. The authors attributed the variation to the different types of helping behaviors of students. High-performing students provided the answers, while students with low reasoning ability had to work collectively through the material. In terms of Vygotsky (1978) , this finding provided new insights into the learning context in which productive interactions can occur for students.

Another consideration in the selection and use of a theoretical framework pertains to its orientation to the study. This can result in the theoretical framework prioritizing individuals, institutions, and/or policies ( Anfara and Mertz, 2014 ). Frameworks that connect to individuals, for instance, could contribute to understanding their actions, learning, or knowledge. Institutional frameworks, on the other hand, offer insights into how institutions, organizations, or groups can influence individuals or materials. Policy theories provide ways to understand how national or local policies can dictate an emphasis on outcomes or instructional design. These different types of frameworks highlight different aspects in an educational setting, which influences the design of the study and the collection of data. In addition, these different frameworks offer a way to make sense of the data. Aligning the data collection and analysis with the framework ensures that a study is coherent and can contribute to the field.

New understandings emerge when different theoretical frameworks are used. For instance, Ebert-May et al. (2015) prioritized the individual level within conceptual change theory (see Posner et al. , 1982 ). In this theory, an individual’s knowledge changes when it no longer fits the phenomenon. Ebert-May et al. (2015) designed a professional development program challenging biology postdoctoral scholars’ existing conceptions of teaching. The authors reported that the biology postdoctoral scholars’ teaching practices became more student-centered as they were challenged to explain their instructional decision making. According to the theory, the biology postdoctoral scholars’ dissatisfaction in their descriptions of teaching and learning initiated change in their knowledge and instruction. These results reveal how conceptual change theory can explain the learning of participants and guide the design of professional development programming.

The communities of practice (CoP) theoretical framework ( Lave, 1988 ; Wenger, 1998 ) prioritizes the institutional level , suggesting that learning occurs when individuals learn from and contribute to the communities in which they reside. Grounded in the assumption of community learning, the literature on CoP suggests that, as individuals interact regularly with the other members of their group, they learn about the rules, roles, and goals of the community ( Allee, 2000 ). A study conducted by Gehrke and Kezar (2017) used the CoP framework to understand organizational change by examining the involvement of individual faculty engaged in a cross-institutional CoP focused on changing the instructional practice of faculty at each institution. In the CoP, faculty members were involved in enhancing instructional materials within their department, which aligned with an overarching goal of instituting instruction that embraced active learning. Not surprisingly, Gehrke and Kezar (2017) revealed that faculty who perceived the community culture as important in their work cultivated institutional change. Furthermore, they found that institutional change was sustained when key leaders served as mentors and provided support for faculty, and as faculty themselves developed into leaders. This study reveals the complexity of individual roles in a COP in order to support institutional instructional change.

It is important to explicitly state the theoretical framework used in a study, but elucidating a theoretical framework can be challenging for a new educational researcher. The literature review can help to identify an applicable theoretical framework. Focal areas of the review or central terms often connect to assumptions and assertions associated with the framework that pertain to the phenomenon of interest. Another way to identify a theoretical framework is self-reflection by the researcher on personal beliefs and understandings about the nature of knowledge the researcher brings to the study ( Lysaght, 2011 ). In stating one’s beliefs and understandings related to the study (e.g., students construct their knowledge, instructional materials support learning), an orientation becomes evident that will suggest a particular theoretical framework. Theoretical frameworks are not arbitrary , but purposefully selected.

With experience, a researcher may find expanded roles for theoretical frameworks. Researchers may revise an existing framework that has limited explanatory power, or they may decide there is a need to develop a new theoretical framework. These frameworks can emerge from a current study or the need to explain a phenomenon in a new way. Researchers may also find that multiple theoretical frameworks are necessary to frame and explore a problem, as different frameworks can provide different insights into a problem.

Creswell, J. W. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. This book provides an overview of theoretical frameworks in general educational research.

Ding, L. (2019). Theoretical perspectives of quantitative physics education research. Physical Review Physics Education Research , 15 (2), 020101-1–020101-13. This paper illustrates how a DBER field can use theoretical frameworks.

Nehm, R. (2019). Biology education research: Building integrative frameworks for teaching and learning about living systems. Disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Science Education Research , 1 , ar15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43031-019-0017-6 . This paper articulates the need for studies in BER to explicitly state theoretical frameworks and provides examples of potential studies.

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice . Sage. This book also provides an overview of theoretical frameworks, but for both research and evaluation.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORKS

Purpose of a conceptual framework.

A conceptual framework is a description of the way a researcher understands the factors and/or variables that are involved in the study and their relationships to one another. The purpose of a conceptual framework is to articulate the concepts under study using relevant literature ( Rocco and Plakhotnik, 2009 ) and to clarify the presumed relationships among those concepts ( Rocco and Plakhotnik, 2009 ; Anfara and Mertz, 2014 ). Conceptual frameworks are different from theoretical frameworks in both their breadth and grounding in established findings. Whereas a theoretical framework articulates the lens through which a researcher views the work, the conceptual framework is often more mechanistic and malleable.

Conceptual frameworks are broader, encompassing both established theories (i.e., theoretical frameworks) and the researchers’ own emergent ideas. Emergent ideas, for example, may be rooted in informal and/or unpublished observations from experience. These emergent ideas would not be considered a “theory” if they are not yet tested, supported by systematically collected evidence, and peer reviewed. However, they do still play an important role in the way researchers approach their studies. The conceptual framework allows authors to clearly describe their emergent ideas so that connections among ideas in the study and the significance of the study are apparent to readers.

Constructing Conceptual Frameworks

Including a conceptual framework in a research study is important, but researchers often opt to include either a conceptual or a theoretical framework. Either may be adequate, but both provide greater insight into the research approach. For instance, a research team plans to test a novel component of an existing theory. In their study, they describe the existing theoretical framework that informs their work and then present their own conceptual framework. Within this conceptual framework, specific topics portray emergent ideas that are related to the theory. Describing both frameworks allows readers to better understand the researchers’ assumptions, orientations, and understanding of concepts being investigated. For example, Connolly et al. (2018) included a conceptual framework that described how they applied a theoretical framework of social cognitive career theory (SCCT) to their study on teaching programs for doctoral students. In their conceptual framework, the authors described SCCT, explained how it applied to the investigation, and drew upon results from previous studies to justify the proposed connections between the theory and their emergent ideas.

In some cases, authors may be able to sufficiently describe their conceptualization of the phenomenon under study in an introduction alone, without a separate conceptual framework section. However, incomplete descriptions of how the researchers conceptualize the components of the study may limit the significance of the study by making the research less intelligible to readers. This is especially problematic when studying topics in which researchers use the same terms for different constructs or different terms for similar and overlapping constructs (e.g., inquiry, teacher beliefs, pedagogical content knowledge, or active learning). Authors must describe their conceptualization of a construct if the research is to be understandable and useful.

There are some key areas to consider regarding the inclusion of a conceptual framework in a study. To begin with, it is important to recognize that conceptual frameworks are constructed by the researchers conducting the study ( Rocco and Plakhotnik, 2009 ; Maxwell, 2012 ). This is different from theoretical frameworks that are often taken from established literature. Researchers should bring together ideas from the literature, but they may be influenced by their own experiences as a student and/or instructor, the shared experiences of others, or thought experiments as they construct a description, model, or representation of their understanding of the phenomenon under study. This is an exercise in intellectual organization and clarity that often considers what is learned, known, and experienced. The conceptual framework makes these constructs explicitly visible to readers, who may have different understandings of the phenomenon based on their prior knowledge and experience. There is no single method to go about this intellectual work.

Reeves et al. (2016) is an example of an article that proposed a conceptual framework about graduate teaching assistant professional development evaluation and research. The authors used existing literature to create a novel framework that filled a gap in current research and practice related to the training of graduate teaching assistants. This conceptual framework can guide the systematic collection of data by other researchers because the framework describes the relationships among various factors that influence teaching and learning. The Reeves et al. (2016) conceptual framework may be modified as additional data are collected and analyzed by other researchers. This is not uncommon, as conceptual frameworks can serve as catalysts for concerted research efforts that systematically explore a phenomenon (e.g., Reynolds et al. , 2012 ; Brownell and Kloser, 2015 ).

Sabel et al. (2017) used a conceptual framework in their exploration of how scaffolds, an external factor, interact with internal factors to support student learning. Their conceptual framework integrated principles from two theoretical frameworks, self-regulated learning and metacognition, to illustrate how the research team conceptualized students’ use of scaffolds in their learning ( Figure 1 ). Sabel et al. (2017) created this model using their interpretations of these two frameworks in the context of their teaching.

FIGURE 1. Conceptual framework from Sabel et al. (2017) .

A conceptual framework should describe the relationship among components of the investigation ( Anfara and Mertz, 2014 ). These relationships should guide the researcher’s methods of approaching the study ( Miles et al. , 2014 ) and inform both the data to be collected and how those data should be analyzed. Explicitly describing the connections among the ideas allows the researcher to justify the importance of the study and the rigor of the research design. Just as importantly, these frameworks help readers understand why certain components of a system were not explored in the study. This is a challenge in education research, which is rooted in complex environments with many variables that are difficult to control.

For example, Sabel et al. (2017) stated: “Scaffolds, such as enhanced answer keys and reflection questions, can help students and instructors bridge the external and internal factors and support learning” (p. 3). They connected the scaffolds in the study to the three dimensions of metacognition and the eventual transformation of existing ideas into new or revised ideas. Their framework provides a rationale for focusing on how students use two different scaffolds, and not on other factors that may influence a student’s success (self-efficacy, use of active learning, exam format, etc.).

In constructing conceptual frameworks, researchers should address needed areas of study and/or contradictions discovered in literature reviews. By attending to these areas, researchers can strengthen their arguments for the importance of a study. For instance, conceptual frameworks can address how the current study will fill gaps in the research, resolve contradictions in existing literature, or suggest a new area of study. While a literature review describes what is known and not known about the phenomenon, the conceptual framework leverages these gaps in describing the current study ( Maxwell, 2012 ). In the example of Sabel et al. (2017) , the authors indicated there was a gap in the literature regarding how scaffolds engage students in metacognition to promote learning in large classes. Their study helps fill that gap by describing how scaffolds can support students in the three dimensions of metacognition: intelligibility, plausibility, and wide applicability. In another example, Lane (2016) integrated research from science identity, the ethic of care, the sense of belonging, and an expertise model of student success to form a conceptual framework that addressed the critiques of other frameworks. In a more recent example, Sbeglia et al. (2021) illustrated how a conceptual framework influences the methodological choices and inferences in studies by educational researchers.

Sometimes researchers draw upon the conceptual frameworks of other researchers. When a researcher’s conceptual framework closely aligns with an existing framework, the discussion may be brief. For example, Ghee et al. (2016) referred to portions of SCCT as their conceptual framework to explain the significance of their work on students’ self-efficacy and career interests. Because the authors’ conceptualization of this phenomenon aligned with a previously described framework, they briefly mentioned the conceptual framework and provided additional citations that provided more detail for the readers.

Within both the BER and the broader DBER communities, conceptual frameworks have been used to describe different constructs. For example, some researchers have used the term “conceptual framework” to describe students’ conceptual understandings of a biological phenomenon. This is distinct from a researcher’s conceptual framework of the educational phenomenon under investigation, which may also need to be explicitly described in the article. Other studies have presented a research logic model or flowchart of the research design as a conceptual framework. These constructions can be quite valuable in helping readers understand the data-collection and analysis process. However, a model depicting the study design does not serve the same role as a conceptual framework. Researchers need to avoid conflating these constructs by differentiating the researchers’ conceptual framework that guides the study from the research design, when applicable.

Explicitly describing conceptual frameworks is essential in depicting the focus of the study. We have found that being explicit in a conceptual framework means using accepted terminology, referencing prior work, and clearly noting connections between terms. This description can also highlight gaps in the literature or suggest potential contributions to the field of study. A well-elucidated conceptual framework can suggest additional studies that may be warranted. This can also spur other researchers to consider how they would approach the examination of a phenomenon and could result in a revised conceptual framework.

Maxwell, J. A. (2012). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. Chapter 3 in this book describes how to construct conceptual frameworks.

Ravitch, S. M., & Riggan, M. (2016). Reason & rigor: How conceptual frameworks guide research . Los Angeles, CA: Sage. This book explains how conceptual frameworks guide the research questions, data collection, data analyses, and interpretation of results.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks are all important in DBER and BER. Robust literature reviews reinforce the importance of a study. Theoretical frameworks connect the study to the base of knowledge in educational theory and specify the researcher’s assumptions. Conceptual frameworks allow researchers to explicitly describe their conceptualization of the relationships among the components of the phenomenon under study. Table 1 provides a general overview of these components in order to assist biology education researchers in thinking about these elements.

It is important to emphasize that these different elements are intertwined. When these elements are aligned and complement one another, the study is coherent, and the study findings contribute to knowledge in the field. When literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks are disconnected from one another, the study suffers. The point of the study is lost, suggested findings are unsupported, or important conclusions are invisible to the researcher. In addition, this misalignment may be costly in terms of time and money.

Conducting a literature review, selecting a theoretical framework, and building a conceptual framework are some of the most difficult elements of a research study. It takes time to understand the relevant research, identify a theoretical framework that provides important insights into the study, and formulate a conceptual framework that organizes the finding. In the research process, there is often a constant back and forth among these elements as the study evolves. With an ongoing refinement of the review of literature, clarification of the theoretical framework, and articulation of a conceptual framework, a sound study can emerge that makes a contribution to the field. This is the goal of BER and education research.

- Allee, V. ( 2000 ). Knowledge networks and communities of learning . OD Practitioner , 32 (4), 4–13. Google Scholar

- Allen, M. ( 2017 ). The Sage encyclopedia of communication research methods (Vols. 1–4 ). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483381411 Google Scholar

- American Association for the Advancement of Science . ( 2011 ). Vision and change in undergraduate biology education: A call to action . Washington, DC. Google Scholar

- Anfara, V. A., & Mertz, N. T. ( 2014 ). Setting the stage . In Anfara, V. A.Mertz, N. T. (eds.), Theoretical frameworks in qualitative research (pp. 1–22). Sage. Google Scholar

- Boote, D. N., & Beile, P. ( 2005 ). Scholars before researchers: On the centrality of the dissertation literature review in research preparation . Educational Researcher , 34 (6), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x034006003 Google Scholar

- Booth, A., Sutton, A., & Papaioannou, D. ( 2016a ). Systemic approaches to a successful literature review (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. Google Scholar

- Booth, W. C., Colomb, G. G., Williams, J. M., Bizup, J., & Fitzgerald, W. T. ( 2016b ). The craft of research (4th ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Google Scholar

- Creswell, J. W. ( 2018 ). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. Google Scholar

- DeHaan, R. L. ( 2011 ). Education research in the biological sciences: A nine decade review (Paper commissioned by the NAS/NRC Committee on the Status, Contributions, and Future Directions of Discipline Based Education Research) . Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Retrieved May 20, 2022, from www7.nationalacademies.org/bose/DBER_Mee ting2_commissioned_papers_page.html Google Scholar

- Ding, L. ( 2019 ). Theoretical perspectives of quantitative physics education research . Physical Review Physics Education Research , 15 (2), 020101. Google Scholar

- Dirks, C. ( 2011 ). The current status and future direction of biology education research . Paper presented at: Second Committee Meeting on the Status, Contributions, and Future Directions of Discipline-Based Education Research, 18–19 October (Washington, DC) . Retrieved May 20, 2022, from http://sites.nationalacademies.org/DBASSE/BOSE/DBASSE_071087 Google Scholar

- Duran, R. P., Eisenhart, M. A., Erickson, F. D., Grant, C. A., Green, J. L., Hedges, L. V., & Schneider, B. L. ( 2006 ). Standards for reporting on empirical social science research in AERA publications: American Educational Research Association . Educational Researcher , 35 (6), 33–40. Google Scholar

- Institute of Education Sciences & National Science Foundation . ( 2013 ). Common guidelines for education research and development . Retrieved May 20, 2022, from www.nsf.gov/pubs/2013/nsf13126/nsf13126.pdf Google Scholar

- Lave, J. ( 1988 ). Cognition in practice: Mind, mathematics and culture in everyday life . New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Google Scholar

- Lysaght, Z. ( 2011 ). Epistemological and paradigmatic ecumenism in “Pasteur’s quadrant:” Tales from doctoral research . In Official Conference Proceedings of the Third Asian Conference on Education in Osaka, Japan . Retrieved May 20, 2022, from http://iafor.org/ace2011_offprint/ACE2011_offprint_0254.pdf Google Scholar

- Maxwell, J. A. ( 2012 ). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. Google Scholar

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. ( 2014 ). Qualitative data analysis (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. Google Scholar

- Patton, M. Q. ( 2015 ). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice . Los Angeles, CA: Sage. Google Scholar

- Posner, G. J., Strike, K. A., Hewson, P. W., & Gertzog, W. A. ( 1982 ). Accommodation of a scientific conception: Toward a theory of conceptual change . Science Education , 66 (2), 211–227. Google Scholar

- Ravitch, S. M., & Riggan, M. ( 2016 ). Reason & rigor: How conceptual frameworks guide research . Los Angeles, CA: Sage. Google Scholar

- Schwandt, T. A. ( 2000 ). Three epistemological stances for qualitative inquiry: Interpretivism, hermeneutics, and social constructionism . In Denzin, N. K.Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 189–213). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. Google Scholar

- Singer, S. R., Nielsen, N. R., & Schweingruber, H. A. ( 2012 ). Discipline-based education research: Understanding and improving learning in undergraduate science and engineering . Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Google Scholar

- Vygotsky, L. S. ( 1978 ). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Google Scholar

- Wenger, E. ( 1998 ). Communities of practice: Learning as a social system . Systems Thinker , 9 (5), 2–3. Google Scholar

- Maryrose Weatherton and

- Elisabeth E. Schussler

- Sarah L. Eddy, Monitoring Editor

- A case study of a novel summer bridge program to prepare transfer students for research in biological sciences 20 December 2022 | Disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Science Education Research, Vol. 4, No. 1

Submitted: 24 May 2021 Revised: 13 April 2022 Accepted: 26 April 2022

© 2022 J. A. Luft et al. CBE—Life Sciences Education © 2022 The American Society for Cell Biology. This article is distributed by The American Society for Cell Biology under license from the author(s). It is available to the public under an Attribution–Noncommercial–Share Alike 4.0 Unported Creative Commons License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0).

- Skip to search box

- Skip to main content

Princeton University Library

Ecology and evolutionary biology research guide.

- Finding Journal Articles

- Citation Searching

- Finding Books

- Finding News Sources

- Reference Sources

- Requesting Books & Articles

- Creating Bibliographies

- What is a Literature Review?

What is a literature review?

A literature review surveys scholarly articles, books and other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory. The purpose is to offer an overview of significant literature published on a topic.

A literature review may constitute an essential chapter of a thesis or dissertation, or may be a self-contained review of writings on a subject. In either case, its purpose is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to the understanding of the subject under review

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration

- Identify new ways to interpret, and shed light on any gaps in, previous research

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort

- Point the way forward for further research

- Place one's original work (in the case of theses or dissertations) in the context of existing literature

A literature review can be just a simple summary of the sources, but it usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis. A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information. It might give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations. Or it might trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates. And depending on the situation, the literature review may evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant.

Similar to primary research, development of the literature review requires four stages:

- Problem formulation—which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues?

- Literature search—finding materials relevant to the subject being explored

- Data evaluation—determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic

- Analysis and interpretation—discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature

Remember, this is a process and not necessarily a linear one. As you search and evaluate the literature, you may refine your topic or head in a different direction which will take you back to the search stage. In fact, it is useful to evaluate as you go along so you don't spend hours researching one aspect of your topic only to find yourself more interested in another.

The main focus of an academic research paper is to develop a new argument, and a research paper will contain a literature review as one of its parts. In a research paper, you use the literature as a foundation and as support for a new insight that you contribute. The focus of a literature review, however, is to summarize and synthesize the arguments and ideas of others without adding new contributions.

For additional information, including suggestions for the structure of your literature review, see this guide from the University of North Carolina's Writing Center: https://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/literature-reviews/

This <10 minute tutorial from North Carolina State University also provides a good overview of the literature review: https://www.lib.ncsu.edu/tutorials/lit-review/

Finding Examples

While we don't have any examples of an EEB JP literature review, it may be useful to look at other reviews to learn how researchers in the field "summarize and synthesize" the literature. Any research article or dissertation in the sciences will include a section which reviews the literature. Though the section may not be labeled as such, you will quickly recognize it by the number of citations and the discussion of the literature. Another option is to look for Review Articles, which are literature reviews as a stand alone article. Here are some resources where you can find Research Articles, Review Articles and Dissertations:

- Web of Science - If you'd like to limit your results to Review Articles, look to the left side of your results page. There you will see many options to refine your search including the section labeled Document Types. Select "Review" as the document type and click on Refine.

- Scopus - Similar to WoS, you can use the options on the left side of your results page if you'd like to limit the document type. Here you will again choose "Review" and then click on the Limit To button.

- Annual Reviews - All articles in this database are review articles. You can search for your topic or browse in a related subject area.

- Dissertations @ Princeton - Provides access to many Princeton dissertations, full text is available for most published after 1996.