Environmental Issues Essay for Students and Children

500+ words essay on environmental issues.

The environment plays a significant role to support life on earth. But there are some issues that are causing damages to life and the ecosystem of the earth. It is related to the not only environment but with everyone that lives on the planet. Besides, its main source is pollution , global warming, greenhouse gas , and many others. The everyday activities of human are constantly degrading the quality of the environment which ultimately results in the loss of survival condition from the earth.

Source of Environment Issue

There are hundreds of issue that causing damage to the environment. But in this, we are going to discuss the main causes of environmental issues because they are very dangerous to life and the ecosystem.

Pollution – It is one of the main causes of an environmental issue because it poisons the air , water , soil , and noise. As we know that in the past few decades the numbers of industries have rapidly increased. Moreover, these industries discharge their untreated waste into the water bodies, on soil, and in air. Most of these wastes contain harmful and poisonous materials that spread very easily because of the movement of water bodies and wind.

Greenhouse Gases – These are the gases which are responsible for the increase in the temperature of the earth surface. This gases directly relates to air pollution because of the pollution produced by the vehicle and factories which contains a toxic chemical that harms the life and environment of earth.

Climate Changes – Due to environmental issue the climate is changing rapidly and things like smog, acid rains are getting common. Also, the number of natural calamities is also increasing and almost every year there is flood, famine, drought , landslides, earthquakes, and many more calamities are increasing.

Above all, human being and their greed for more is the ultimate cause of all the environmental issue.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

How to Minimize Environment Issue?

Now we know the major issues which are causing damage to the environment. So, now we can discuss the ways by which we can save our environment. For doing so we have to take some measures that will help us in fighting environmental issues .

Moreover, these issues will not only save the environment but also save the life and ecosystem of the planet. Some of the ways of minimizing environmental threat are discussed below:

Reforestation – It will not only help in maintaining the balance of the ecosystem but also help in restoring the natural cycles that work with it. Also, it will help in recharge of groundwater, maintaining the monsoon cycle , decreasing the number of carbons from the air, and many more.

The 3 R’s principle – For contributing to the environment one should have to use the 3 R’s principle that is Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle. Moreover, it helps the environment in a lot of ways.

To conclude, we can say that humans are a major source of environmental issues. Likewise, our activities are the major reason that the level of harmful gases and pollutants have increased in the environment. But now the humans have taken this problem seriously and now working to eradicate it. Above all, if all humans contribute equally to the environment then this issue can be fight backed. The natural balance can once again be restored.

FAQs about Environmental Issue

Q.1 Name the major environmental issues. A.1 The major environmental issues are pollution, environmental degradation, resource depletion, and climate change. Besides, there are several other environmental issues that also need attention.

Q.2 What is the cause of environmental change? A.2 Human activities are the main cause of environmental change. Moreover, due to our activities, the amount of greenhouse gases has rapidly increased over the past few decades.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Search the United Nations

- Issue Briefs

- Commemoration

- Branding Package

- Our Common Agenda

- Press Releases

The Climate Crisis – A Race We Can Win

Climate change is the defining crisis of our time and it is happening even more quickly than we feared. But we are far from powerless in the face of this global threat. As Secretary-General António Guterres pointed out in September, “the climate emergency is a race we are losing, but it is a race we can win”.

No corner of the globe is immune from the devastating consequences of climate change. Rising temperatures are fueling environmental degradation, natural disasters, weather extremes, food and water insecurity, economic disruption, conflict, and terrorism. Sea levels are rising, the Arctic is melting, coral reefs are dying, oceans are acidifying, and forests are burning. It is clear that business as usual is not good enough. As the infinite cost of climate change reaches irreversible highs, now is the time for bold collective action.

GLOBAL TEMPERATURES ARE RISING

Billions of tons of CO2 are released into the atmosphere every year as a result of coal, oil, and gas production. Human activity is producing greenhouse gas emissions at a record high , with no signs of slowing down. According to a ten-year summary of UNEP Emission Gap reports, we are on track to maintain a “business as usual” trajectory.

The last four years were the four hottest on record. According to a September 2019 World Meteorological Organization (WMO) report, we are at least one degree Celsius above preindustrial levels and close to what scientists warn would be “an unacceptable risk”. The 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change calls for holding eventual warming “well below” two degrees Celsius, and for the pursuit of efforts to limit the increase even further, to 1.5 degrees. But if we don’t slow global emissions, temperatures could rise to above three degrees Celsius by 2100 , causing further irreversible damage to our ecosystems.

Glaciers and ice sheets in polar and mountain regions are already melting faster than ever, causing sea levels to rise. Almost two-thirds of the world’s cities with populations of over five million are located in areas at risk of sea level rise and almost 40 per cent of the world’s population live within 100 km of a coast. If no action is taken, entire districts of New York, Shanghai, Abu Dhabi, Osaka, Rio de Janeiro, and many other cities could find themselves underwater within our lifetimes , displacing millions of people.

FOOD AND WATER INSECURITY

Global warming impacts everyone’s food and water security. Climate change is a direct cause of soil degradation, which limits the amount of carbon the earth is able to contain. Some 500 million people today live in areas affected by erosion, while up to 30 per cent of food is lost or wasted as a result. Meanwhile, climate change limits the availability and quality of water for drinking and agriculture.

In many regions, crops that have thrived for centuries are struggling to survive, making food security more precarious. Such impacts tend to fall primarily on the poor and vulnerable. Global warming is likely to make economic output between the world’s richest and poorest countries grow wider .

NEW EXTREMES

Disasters linked to climate and weather extremes have always been part of our Earth’s system. But they are becoming more frequent and intense as the world warms. No continent is left untouched, with heatwaves, droughts, typhoons, and hurricanes causing mass destruction around the world. 90 per cent of disasters are now classed as weather- and climate-related, costing the world economy 520 billion USD each year , while 26 million people are pushed into poverty as a result.

A CATALYST FOR CONFLICT

Climate change is a major threat to international peace and security. The effects of climate change heighten competition for resources such as land, food, and water, fueling socioeconomic tensions and, increasingly often, leading to mass displacement .

Climate is a risk multiplier that makes worse already existing challenges. Droughts in Africa and Latin America directly feed into political unrest and violence. The World Bank estimates that, in the absence of action, more than 140 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and South Asia will be forced to migrate within their regions by 2050.

A PATH FORWARD

While science tells us that climate change is irrefutable, it also tells us that it is not too late to stem the tide. This will require fundamental transformations in all aspects of society — how we grow food, use land, transport goods, and power our economies.

While technology has contributed to climate change, new and efficient technologies can help us reduce net emissions and create a cleaner world. Readily-available technological solutions already exist for more than 70 per cent of today’s emissions. In many places renewable energy is now the cheapest energy source and electric cars are poised to become mainstream.

In the meantime, nature-based solutions provide ‘breathing room’ while we tackle the decarbonization of our economy. These solutions allow us to mitigate a portion of our carbon footprint while also supporting vital ecosystem services, biodiversity, access to fresh water, improved livelihoods, healthy diets, and food security. Nature-based solutions include improved agricultural practices, land restoration, conservation, and the greening of food supply chains.

Scalable new technologies and nature-based solutions will enable us all to leapfrog to a cleaner, more resilient world. If governments, businesses, civil society, youth, and academia work together, we can create a green future where suffering is diminished, justice is upheld, and harmony is restored between people and planet.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

The Sustainable Development Goals

Climate Action Summit 2019

UNFCCC | The Paris Agreement

WMO |Global Climate in 2015-2019

UNDP | Global Outlook Report 2019

UNCC | Climate Action and Support Trends 2019

IPCC | Climate Change and Land 2019

UNEP | Global Environment Outlook 2019

UNEP | Emission Gap Report 2019

PDF VERSION

Download the pdf version

Humans have caused this environmental crisis. It’s time to change how we think about risk

At the sharp end: A flooded road after a heavy rainfall in Mumbai, India Image: REUTERS/Francis Mascarenhas

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Nathanial Matthews

Patrick keys.

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Future of the Environment is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, future of the environment.

Global environmental risks caused by human activities are becoming increasingly complex and interconnected, with far-reaching consequences for people, economies and ecosystems.

We are now in the Anthropocene – a geological epoch where humans are a dominant force of change on the planet. The Anthropocene is characterized by an increasingly interconnected and accelerating world.

This hyper interconnectivity and pace of change demands that we reconceptualize risk. The architecture that connects crises causes their impacts to ripple out in unpredictable ways. This was widely seen in the 2008-2009 financial crisis, which had significant impact on food prices that ultimately drove land grabs in Africa, Asia and South America.

International policy groups have made several, increasingly sophisticated efforts to capture complex risks, using frameworks such as The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report on Reasons for concern regarding climate change risks ; and the World Economic Forum’s annual Global Risks Report .

It’s an annual meeting featuring top examples of public-private cooperation and Fourth Industrial Revolution technologies being used to develop the sustainable development agenda.

It runs alongside the United Nations General Assembly, which this year features a one-day climate summit. This is timely given rising public fears – and citizen action – over weather conditions, pollution, ocean health and dwindling wildlife. It also reflects the understanding of the growing business case for action.

The UN’s Strategic Development Goals and the Paris Agreement provide the architecture for resolving many of these challenges. But to achieve this, we need to change the patterns of production, operation and consumption.

The World Economic Forum’s work is key, with the summit offering the opportunity to debate, discuss and engage on these issues at a global policy level.

While environmental risks – such as water stress and extreme weather – play a growing role in these assessments, the literature on global systemic risk has hitherto been dominated by finance and technology. This is, in part, due to the value placed on markets and technological solutions. Although all of these initiatives contribute in important ways to current understandings of global risks, none of them are able to fully capture the human–environmental processes that are shaping new systemic environmental risks.

A recent paper published in the journal of Nature Sustainability, emphasizes the need to embrace concepts of global, human-driven, environmental risks and interactions that move across very large scales of space and time. This is not just a question of adjusting quarterly financial outlooks to consider the next five or ten years. The non-linear and complex reality of humanity’s changes to the entire Earth system, require us to look much further forward and backward in time.

The authors highlight four case studies that examine different dimensions of Anthropocene risk. For example, it turns out that groundwater extraction for Indian irrigation leads to increased rainfall in East Africa . However, if India moves towards more sustainable groundwater extraction, that could lead to a trade-off in countries that may now be reliant on changed precipitation.

Another case study considers coastal megacities and the long-term prospects of sea level rise. By 2100, global sea levels could rise by as much as two metres , with some regions experiencing even higher levels. That is a problem for investments being made today in built infrastructure that is intended to last for 50 years or more.

The Anthropocene as a concept is itself a contested notion. The idea that all of humanity is somehow responsible for the current crisis does not reflect the reality. Specifically, a significant amount of the world’s wealthy and powerful accrued their wealth and power on the back of carbon emissions . This disparity between those that emitted carbon and became rich, and those that have not emitted carbon and remain poor, is a defining feature of Anthropocene risk.

It may seem odd to emphasize power imbalances when considering global environmental risks. However, the non-linear and complex reality of the Anthropocene suggests that the prevailing international order will not last, and that addressing our past and present problems is necessary to chart an equitable and sustainable future.

What is the World Economic Forum’s Sustainable Development Impact summit?

The wealth and power that many organizations and people have accrued while emitting significant amounts of carbon should be mobilized, in significant part, to start addressing the pronounced environmental and social injustices that are perpetuating these Anthropocene risks. This is already occurring to some degree, but needs to be accelerated.

As the world enters a new era of surprise and uncertainty, a pronounced opportunity exists to embrace a different economic model for the future. This requires doing things differently, such as engaging with social and environmental justice organizations.

Acclaimed physicist Richard Feynman once said: “If we want to solve a problem that we have never solved before, we must leave the door to the unknown ajar.”

Humanity has never faced the types of changes that we are facing today and will continue to face in the decades to come. The scale of economic, environmental, geopolitical, and social changes that the Anthropocene will bring to our doorstep has no precedent. So, as Feynman suggests, the door must be left open to allow new ideas and solutions to enter in.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Future of the Environment .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

4 charts to show why adopting a circular economy matters

Victoria Masterson

April 4, 2024

4 lessons from Jane Goodall as the renowned primatologist turns 90

Gareth Francis

April 3, 2024

What to do with ageing oil and gas platforms – and why it matters

April 2, 2024

Melting ice caps slowing Earth's rotation, study shows, and other nature and climate stories you need to read this week

Johnny Wood

2023 the hottest year on record, and other nature and climate stories you need to read this week

Meg Jones and Joe Myers

March 25, 2024

What is World Water Day?

March 22, 2024

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Herbert Chanoch Kelman, 94

Exploring generative AI at Harvard

Everett irwin mendelsohn, 91, eyes on tomorrow, voices of today.

Candice Chen ’22 (left) and Noah Secondo ’22.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Alvin Powell

Harvard Staff Writer

Harvard students share thoughts, fears, plans to meet environmental challenges

For many, thinking about the world’s environmental future brings concern, even outright alarm.

There have been, after all, decades of increasingly strident warnings by experts and growing, ever-more-obvious signs of the Earth’s shifting climate. Couple this with a perception that past actions to address the problem have been tantamount to baby steps made by a generation of leaders who are still arguing about what to do, and even whether there really is a problem.

It’s no surprise, then, that the next generation of global environmental leaders are preparing for their chance to begin work on the problem in government, business, public health, engineering, and other fields with a real sense of mission and urgency.

The Gazette spoke to students engaged in environmental action in a variety of ways on campus to get their views of the problem today and thoughts on how their activities and work may help us meet the challenge.

Eric Fell and Eliza Spear

Fell is president and Spear is vice president of Harvard Energy Journal Club. Fell is a graduate student at the Harvard John H. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and Spear is a graduate student in the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology.

FELL: For the past three centuries, fossil fuels have enabled massive growth of our civilization to where we are today. But it is now time for a new generation of cleaner-energy technologies to fuel the next chapter of humanity’s story. We’re not too late to solve this environmental challenge, but we definitely shouldn’t procrastinate as much as we have been. I don’t worry about if we’ll get it done, it’s the when. Our survival depends on it. At Harvard, I’ve been interested in the energy-storage problem and have been focusing on developing a grid-scale solution utilizing flow batteries based on organic molecules in the lab of Mike Aziz . We’ll need significant deployment of batteries to enable massive penetration of renewables into the electrical grid.

SPEAR: Processes leading to greenhouse-gas emissions are so deeply entrenched in our way of life that change continues to be incredibly slow. We need to be making dramatic structural changes, and we should all be very worried about that. In the Harvard Energy Journal Club, our focus is energy, so we strive to learn as much as we can about the diverse options for clean-energy generation in various sectors. A really important aspect of that is understanding how much of an impact those technologies, like solar, hydro, and wind, can really have on reducing greenhouse-gas emissions. It’s not always as much as you’d like to believe, and there are still a lot of technical and policy challenges to overcome.

I can’t imagine working on anything else, but the question of what I’ll be working on specifically is on my mind a lot. The photovoltaics field is at a really exciting point where a new technology is just starting to break out onto the market, so there are a lot of opportunities for optimization in terms of performance, safety, and environmental impact. That’s what I’m working on now [in Roy Gordon’s lab ] and I’m really enjoying it. I’ll definitely be in the renewable-energy technology realm. The specifics will depend on where I see the greatest opportunity to make an impact.

Photo (left) courtesy of Kritika Kharbanda; photo by Tiera Satchebell.

Kritika Kharbanda ’23 and Laier-Rayshon Smith ’21

Kharbanda is with the Harvard Student Climate Change Conference, Harvard Circular Economy Symposium. Smith is a member of Climate Leaders Program for Professional Students at Harvard. Both are students at Harvard Graduate School of Design.

KHARBANDA: I come from a country where the most pressing issues are, and will be for a long time, poverty, food shortage, and unemployment born out of corruption, illiteracy, and rapid gentrification. India was the seventh-most-affected country by climate change in 2019. With two-thirds of the population living in rural areas with no access to electricity, even the notion of climate change is unimaginable.

I strongly believe that the answer lies in the conjugality of research and industry. In my field, achieving circularity in the building material processes is the burning concern. The building industry currently contributes to 40 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions, of which 38 percent is contributed by the embedded or embodied energy used for the manufacturing of materials. A part of the Harvard i-lab, I am a co-founder of Cardinal LCA, an early stage life-cycle assessment tool that helps architects and designers visualize this embedded energy in building materials, saving up to 46 percent of the energy from the current workflow. This venture has a strong foundation as a research project for a seminar class I took at the GSD in fall 2020, instructed by Jonathan Grinham. I am currently working as a sustainability engineer at Henning Larsen architects in Copenhagen while on a leave of absence from GSD. In the decades to come, I aspire to continue working on the embodied carbon aspect of the building industry. Devising an avant garde strategy to record the embedded carbon is the key. In the end, whose carbon is it, anyway?

SMITH: The biggest challenges are areas where the threat of climate change intersects with environmental justice. It is important that we ensure that climate-change mitigation and adaptation strategies are equitable, whether it is sea-level rise or the increase in urban heat islands. We should seek to address the threats faced by the most vulnerable communities — the communities least able to resolve the threat themselves. These often tend to be low-income communities and communities of color that for decades have been burdened with bearing the brunt of environmental health hazards.

During my time at Harvard, I have come to understand how urban planning and design can seek to address this challenge. Planners and designers can develop strategies to prioritize communities that are facing a significant climate-change risk, but because of other structural injustices may not be able to access the resources to mitigate the risk. I also learned about climate gentrification: a phenomenon in which people in wealthier communities move to areas with lower risks of climate-change threats that are/were previously lower-income communities. I expect to work on many of these issues, as many are connected and are threats to communities across the country. From disinvestment and economic extraction to the struggle to find quality affordable housing, these injustices allow for significant disparities in life outcomes and dealing with risk.

Lucy Shaw ’21

Shaw is co-president of the HBS Energy and Environment Club. She is a joint-degree student at Harvard Business School and Harvard Kennedy School.

SHAW: I want to see a world where climate change is averted and the environment preserved, without it being at the expense of the development and prosperity of lower-income countries. We have, or are on the cusp of having, many of the financial and technological tools we need to reduce emissions and environmental damage from a wide array of industries, such as agriculture, energy, and transport. The challenge I am most worried about is how we balance economic growth and opportunity with reducing humanity’s environmental impact and share this burden equitably across countries.

I came to Harvard as a joint degree student at the Kennedy School and Business School to be able to see this challenge from two different angles. In my policy-oriented classes, we learned about the opportunities and challenges of global coordination among national governments — the difficulty in enforcing climate agreements, and in allocating and agreeing on who bears the responsibility and the costs of change, but also the huge potential that an international framework with nationally binding laws on environmental protection and carbon-emission reduction could have on changing the behavior of people and businesses. In my business-oriented classes, we learned about the power of business to create change, if there is a driven leadership. We also learned that people and businesses respond to incentives, and the importance of reducing cost of technologies or increasing the cost of not switching to more sustainable technologies — for example, through a tax. After graduate school, I plan to join a leading private equity investor in their growing infrastructure team, which will equip me with tools to understand what makes a good investment in infrastructure and what are the opportunities for reducing the environmental impact of infrastructure while enhancing its value. I hope to one day be involved in shaping environmental and development policy, whether it is on a national or international level.

Photo (left) by Tabitha Soren.

Quinn Lewis ’23 and Suhaas Bhat ’24

Both are with the Student Climate Change Conference, Harvard College.

LEWIS: When I was a kid, I imagined being an adult as a future with a stable house, a fun job, and happy kids. That future didn’t include wildfires that obscured the sun for months, global water shortages, or billionaires escaping to terrariums on Mars. The threats are so great and so assured by inaction that it’s very hard for me to justify doing anything else with my time and attention because very little will matter if there’s 1 billion climate refugees and significant portions of the continental United States become uninhabitable for human life.

For whatever reason, I still feel a great deal of hope around giving it a shot. I can’t imagine not working to mitigate the climate crisis. Media and journalism will play a huge role in raising awareness, as they generate public pressure that can sway those in power. Another route for change is to cut directly to those in power and try to convince them of the urgency of the situation. Given that I am 22 years old, it is much easier to raise public awareness or work in media and journalism than it is to sit down with some of the most powerful people on the planet, who tend to be rather busy. At school, I’m on a team that runs the University-wide Student Climate Change Conference at Harvard, which is a platform for speakers from diverse backgrounds to discuss the climate crisis and ways students and educators can take immediate and effective action. Also, I write about and research challenges and solutions to the climate crisis through the lenses of geopolitics and the global economy, both as a student at the College and as a case writer at the Harvard Business School. Outside of Harvard, I have worked in investigative journalism and at Crooked Media, as well as on political campaigns to indirectly and directly drive urgency around the climate crisis.

BHAT: The failure to act on climate change in the last few decades, despite mountains of scientific evidence, is a consequence of political and institutional cowardice. Fossil fuel companies have obfuscated, misinformed, and lobbied for decades, and governments have failed to act in the best interests of their citizens. Of course, the fight against climate change is complex and multidimensional, requiring scientific, technical, and entrepreneurial expertise, but it will ultimately require systemic change to allow these talents to shine.

At Harvard, my work on climate has been focused on running the Harvard Student Climate Conference, as well as organizing for Fossil Fuel Divest Harvard. My hope for the Climate Conference is to provide students access to speakers who have dedicated their careers to all aspects of the fight against climate change, so that students interested in working on climate have more direction and inspiration for what to do with their careers. We’ve featured Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley, members of the Sunrise Movement, and the CEO of Impossible Foods as some examples of inspiring and impactful people who are working against climate change today.

I organize for FFDH because I believe that serious institutional change is necessary for solving the climate crisis and also because of a sort of patriotism I have for Harvard. I deeply respect and care for this institution, and genuinely believe it is an incredible force for good in the world. At the same time, I believe Harvard has a moral duty to stand against the corporations whose misdeeds and falsification of science have enabled the climate crisis.

Libby Dimenstein ’22

Dimenstein is co-president of Harvard Law School Environmental Law Society.

DIMENSTEIN: Climate change is the one truly existential threat that my generation has had to face. What’s most scary is that we know it’s happening. We know how bad it will be; we know people are already dying from it; and we still have done so little relative to the magnitude of the problem. I also worry that people don’t see climate change as an “everyone problem,” and more as a problem for people who have the time and money to worry about it, when in reality it will harm people who are already disadvantaged the most.

I want to recognize Professor Wendy Jacobs, who recently passed away. Wendy founded HLS’s fantastic Environmental Law and Policy Clinic, and she also created an interdisciplinary class called the Climate Solutions Living Lab. In the lab, groups of students drawn from throughout the University would conduct real-world projects to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions. The class was hard, because actually reducing greenhouse gases is hard, but it taught us about the work that needs to be done. This summer I’m interning with the Environmental Defense Fund’s U.S. Clean Air Team, and I anticipate a lot of my work will revolve around the climate. After graduating, I’m hoping to do environmental litigation, either with a governmental division or a nonprofit, but I also have an interest in policy work: Impact litigation is fascinating and important, but what we need most is sweeping policy change.

Candice Chen ’22 and Noah Secondo ’22

Chen and Secondo are co-directors of the Harvard Environmental Action Committee. Both attend Harvard College.

SECONDO: The environment is fundamental to rural Americans’ identity, but they do not believe — as much as urban Americans — that the government can solve environmental problems. Without the whole country mobilized and enthusiastic, from New Hampshire to Nebraska, we will fail to confront the climate crisis. I have no doubt that we can solve this problem. To rebuild trust between the U.S. government and rural communities, federal departments and agencies need to speak with rural stakeholders, partner with state and local leaders, and foreground rural voices. Through the Harvard College Democrats and the Environmental Action Committee, I have contributed to local advocacy efforts and creative projects, including an environmental art publication.

I hope to work in government to keep the policy development and implementation processes receptive to rural perspectives, including in the environmental arena. At every level of government, if we work with each other in good faith, we will tackle the climate crisis and be better for it.

CHEN: I’m passionate about promoting more sustainable, plant-based diets. As individual consumers, we have very little control over the actions of the largest emitters, massive corporations, but we can all collectively make dietary decisions that can avoid a lot of environmental degradation. Our food system is currently very wasteful, and our overreliance on animal agriculture devastates natural ecosystems, produces lots of potent greenhouse gases, and creates many human health hazards from poor animal-waste disposal. I feel like the climate conversation is often focused around the clean energy transition, and while it is certainly the largest component of how we can avoid the worst effects of global warming, the dietary conversation is too often overlooked. A more sustainable future also requires us to rethink agriculture, and especially what types of agriculture our government subsidizes. In the coming years, I hope that more will consider the outsized environmental impact of animal agriculture and will consider making more plant-based food swaps.

To raise awareness of the environmental benefits of adopting a more plant-based diet, I’ve been involved with running a campaign through the Environmental Action Committee called Veguary. Veguary encourages participants to try going vegetarian or vegan for the month of February, and participants receive estimates for how much their carbon/water/land use footprints have changed based on their pledged dietary changes for the month.

Photo (left) courtesy of Cristina Su Liu.

Cristina Su Liu ’22 and James Healy ’21

More like this.

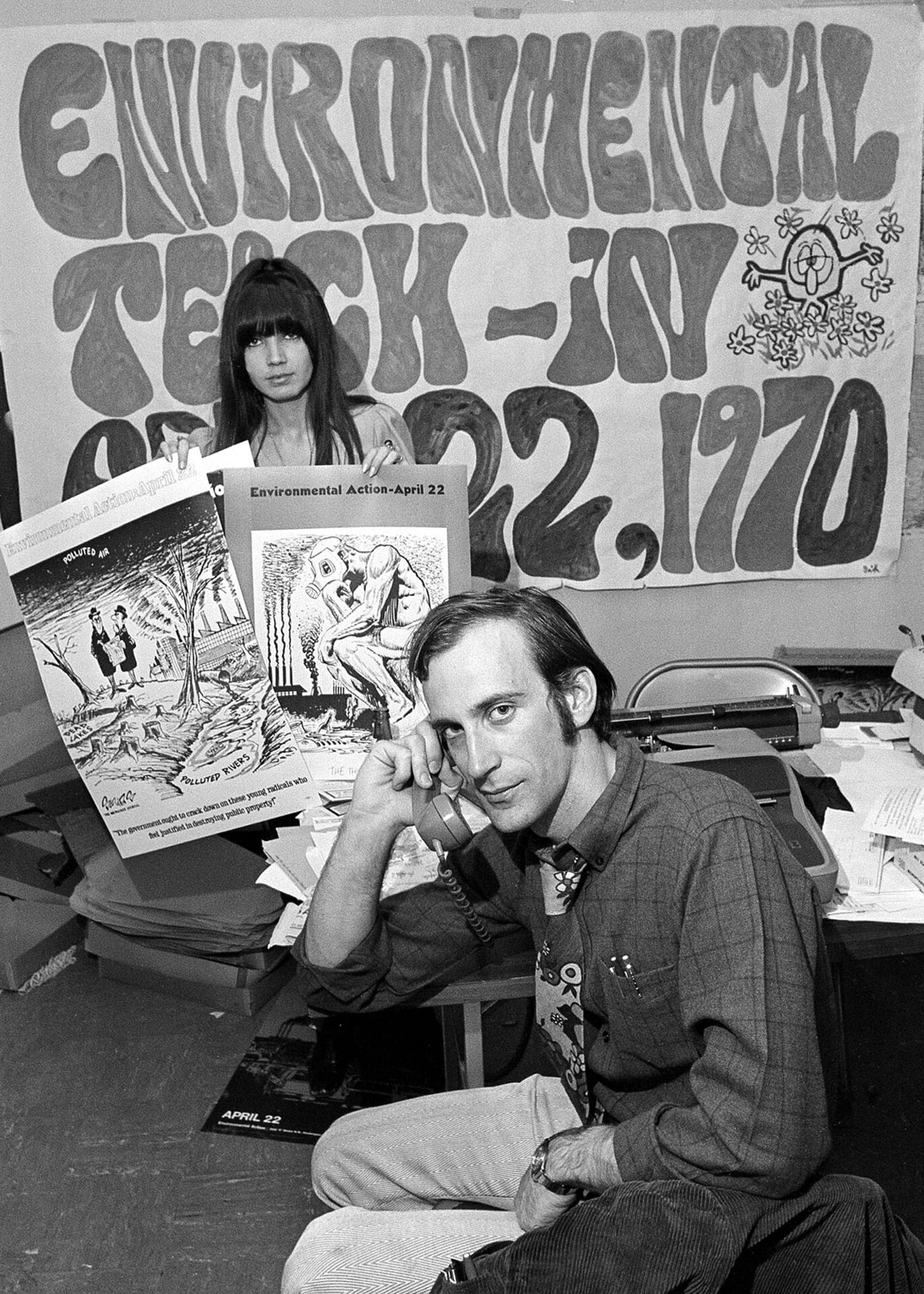

How Earth Day gave birth to environmental movement

The culture of Earth Day

Spirituality, social justice, and climate change meet at the crossroads

Liu is with Harvard Climate Leaders Program for Professional Students. Healy is with the Harvard Student Climate Change Conference. Both are students at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

HEALY: As a public health student I see so many environmental challenges, be it the 90 percent of the world who breathe unhealthy air, or the disproportionate effects of extreme heat on communities of color, or the environmental disruptions to the natural world and the zoonotic disease that humans are increasingly being exposed to. But the central commonality at the heart of all these crises is the climate crisis. Climate change, from the greenhouse-gas emissions to the physical heating of the Earth, is worsening all of these environmental crises. That’s why I call the climate crisis the great exacerbator. While we will all feel the effects of climate change, it will not be felt equally. Whether it’s racial inequity or wealth inequality, the climate crisis is widening these already gaping divides.

Solutions may have to be outside of our current road maps for confronting crises. I have seen the success of individual efforts and private innovation in tackling the COVID-19 pandemic, from individuals wearing masks and social distancing to the huge advances in vaccine development. But for climate change, individual efforts and innovation won’t be enough. I would be in favor of policy reform and coalition-building between new actors. As an overseer of the Harvard Student Climate Change Conference and the Harvard Climate Leaders Program, I’ve aimed to help mobilize Harvard’s diverse community to tackle climate change. I am also researching how climate change makes U.S. temperatures more variable, and how that’s reducing the life expectancies of Medicare recipients. The goal of this research, with Professor Joel Schwartz, will be to understand the effects of climate change on vulnerable communities. I certainly hope to expand on these themes in my future work.

SU LIU: A climate solution will need to be a joint effort from the whole society, not just people inside the environmental or climate circles. In addition to cross-sectoral cooperation, solving climate change will require much stronger international cooperation so that technologies, projects, and resources can be developed and shared globally. As a Chinese-Brazilian student currently studying in the United States, I find it very valuable to learn about the climate challenges and solutions of each of these countries, and how these can or cannot be applied in other settings. China-U.S. relations are tense right now, but I hope that climate talks can still go ahead since we have much to learn from each other.

Personally, as a student in environmental health at [the Harvard Chan School], I feel that my contribution to addressing this challenge until now has been in doing research, learning more about the health impacts of climate change, and most importantly, learning how to communicate climate issues to people outside climate circles. Every week there are several climate-change events at Harvard, where a different perspective on climate change is addressed. It has been very inspiring for me, and I feel that I could learn about climate change in a more holistic way.

Recently, I started an internship at FXB Village, where I am working on developing and integrating climate resilience indicators into their poverty-alleviation program in rural communities in Puebla, Mexico. It has been very rewarding to introduce climate-change and climate-resilience topics to people working on poverty alleviation and see how everything is interconnected. When we address climate resilience, we are also addressing access to basic services, livelihoods, health, equity, and quality of life in general. This is where climate justice is addressed, and that is a very powerful idea.

Share this article

You might like.

Memorial Minute — Faculty of Arts and Sciences

Leaders weigh in on where we are and what’s next

Forget ‘doomers.’ Warming can be stopped, top climate scientist says

Michael Mann points to prehistoric catastrophes, modern environmental victories

Yes, it’s exciting. Just don’t look at the sun.

Lab, telescope specialist details Harvard eclipse-viewing party, offers safety tips

College accepts 1,937 to Class of 2028

Students represent 94 countries, all 50 states

Friday essay: thinking like a planet - environmental crisis and the humanities

Emeritus Professor of History, Australian National University

Disclosure statement

Tom Griffiths does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Australian National University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Many of us joined the Global Climate Strike on Friday, 20 September, and together we constituted half a million Australians gathering peacefully and walking the streets of our cities and towns to protest at government inaction in the face of the gravest threat human civilisation has faced.

It was a global strike, but its Australian manifestation had a particular twist, for our own federal government is an international pariah on this issue. We have become the Ugly Australians, led by brazen climate deniers who trash the science and snub the UN Climate Summit.

Government politicians in Canberra constantly tell us the Great Barrier Reef is fine, coal is good for humanity, Pacific islands are floating not being flooded, wind turbines are obscene, power blackouts are due to renewables, “drought-proofing” is urgent but “climate-change” has nothing to do with it, science is a conspiracy, climate protesters are a “scourge” who deserve to be punished and jailed, the ABC spins the weather, the Bureau of Meteorology requires a royal commission, the United Nations is a bully, if we have to have emissions targets, well, we are exceeding them, and Australia is so insignificant in the world it doesn’t have to act anyway.

It’s a wilful barrage of lies, an insult to the public, a threat to civil society, and an extraordinary attack on our intelligence by our own elected representatives.

The international Schools4Climate movement is remarkable because it is led by children, teenagers still at school advocating a future they hope to have. I can’t think of another popular protest movement in world history led by children. This could be a transformative moment in global politics; it certainly needs to be. The active presence of so many engaged children gave the rally a spirit and a lightness in spite of its grim subject; there was a sense of fun, a family feeling about the occasion, but there was a steely resolve too.

A girl in a school uniform standing next to me at the rally held a copy of George Orwell’s 1984 in her hands. Many of the people around me would normally expect to see in the 22nd century. Their power, paradoxically, is they are not voters. They didn’t elect this government! They are protesting not just against the governments of the world but also against us adults, who did elect these politicians or who abide them. There was a moment at the rally when, with the mysterious organic coherence crowds possess, the older protesters stepped aside, parting like a wave, and formed a guard of honour through the centre of which the children marched holding their placards, their leadership acknowledged.

Read more: Guide to the classics: Orwell's 1984 and how it helps us understand tyrannical power today

One placard declared: “You’ll die of old age; I’ll die of climate change”; another said: “If Earth were cool, I’d be in school.” One held up a large School Report Card with subject results: “Ethics X, Responsibility X, Climate Action X. Needs to try harder.” Another explained: “You skip summits, we skip school.”

In Melbourne, as elsewhere, teenagers gave the speeches; and they were passionate and eloquent. The demands of the movement are threefold: no new coal, oil and gas projects; 100% renewable energy generation and exports by 2030; and fund a just transition and job creation for all fossil-fuel workers and communities. There were also Indigenous speakers. One declared: “We stand for you too, when we stand for Country.”

There were 150,000 people in the Melbourne Treasury Gardens, a crowd so large responsive cheers rippled like a Mexican wave up the hill from the speakers. I reflected on the historical parallels for what was unfolding, recalling the Vietnam moratorium demonstrations and the marches against the first Gulf War, the Freedom Rides and the civil rights movement, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy and the suffragettes’ campaigns.

Inspired by this history, we now have the Extinction Rebellion , a movement born in a small British town late last year which declares “only non-violent rebellion can now stop climate breakdown and social collapse”. Within six months, through civil disobedience, it brought central London to a standstill and the United Kingdom became the first country to declare a climate emergency. We are at a political tipping point.

In Australia, the result of this year’s election tells us there is no accountability for probably the most dysfunctional and discredited federal government in our history, and now we are left with a parliament unwilling to act on so many vital national and international issues. The 2019 federal election was no status quo outcome, as some political commentators have declared. Rather, it was a radical result, revealing deep structural flaws in our parliamentary democracy, our media culture and our political discourse. For me it ranks with two other elections in my voting lifetime: the “dark victory” of the 2001 Tampa election , and the 1975 constitutional crisis . Like those earlier dates, 2019 could shape and shadow a generation. It is time to get out on the streets again.

Skolstrejk för klimatet

The founder, symbol and the voice of the School Strike movement is, of course, Greta Thunberg. It is just over a year since August 2018 when she began to spend every Friday away from class sitting outside the Swedish parliament with a handmade sign declaring “School Strike for the Climate”.

When she told her parents about her plans, she reported “they weren’t very fond of it”. Addressing the UN Climate Change Conference in December 2018, she said : “You are not mature enough to tell it like it is. Even that burden you leave to your children.” Thunberg quietly invokes the carbon budget and the galling fact there is already so much carbon in the system “there is simply not enough time to wait for us to grow up and become the ones in charge.”

In late September, Thunberg gave a powerful presentation at the UN Climate Summit; Richard Flanagan compared her 495-word UN speech to Abraham Lincoln’s 273-word Gettysburg Address. It’s a reasonable parallel that reaches for some understanding of the enormity of this political moment.

It is sickening to see the speed with which privileged old white men have rushed to pour bile on this young woman. Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin quickly recognised her power and sought to neutralise and patronise her. Scott Morrison chimed in. Australia’s locker room of shock jocks laced the criticism with some misogyny. It’s amazing how they froth at the mouth about a calm and articulate schoolgirl. They are all – directly or indirectly – in the pockets of the fossil fuel industry.

Read more: Misogyny, male rage and the words men use to describe Greta Thunberg

Denialism is worthy of study . I don’t mean the conscious and fraudulent denialism of politicians and shock-jocks such as those I’ve mentioned. That’s pretty simple stuff – lies motivated by opportunism, greed and personal advancement, and funded by the carbon-polluting industries. It is appalling but boring.

There are more interesting forms of denialism, such as the emotional denialism we all inhabit. Emotional denialism in the face of the unthinkable can take many forms – avoidance, hope, anxiety, even a kind of torpor when people truly begin to understand what will happen to the world of their grandchildren. We are all prone to this willing blindness and comforting self-delusion. Overcoming that is our greatest challenge.

And there is a third kind of denialism that should especially interest scholars. It is when some of our own kind – scholars trained to respect evidence – fashion themselves as sceptics, but are actually dogged contrarians.

Read more: There are three types of climate change denier, and most of us are at least one

One example is Niall Ferguson, a Scottish historian and professor of history at Harvard University, who calls climate science “science fiction” and recently joined the ranks of old, white, privileged men commenting on the appearance of Greta Thunberg. I’m not arguing here with Ferguson’s politics – he is an arch-conservative and I do disagree with his politics, but I also believe engaged, reflective politics can drive good history.

Rather, Ferguson’s disregard for evidence and neglect of science and scholarship attracts my attention. His understanding of climate science and climate history is poor: in a recent article in the Boston Globe he assumed the Little Ice Age started in the 17th century, whereas its beginning was three centuries earlier .

How does a trained scholar, a professor of history, get themselves in this ignominious position? For Ferguson, contrarianism has been a productive intellectual strategy – going against the flow of fashion is a good scholarly instinct – but on climate change his politics and the truth have steadily travelled in different directions and caught him out. We can say the same of Geoffrey Blainey, another successful contrarian who has cornered himself on climate change . Like Ferguson he appears uninterested in decades of significant research in environmental history – and thus his healthy scepticism has morphed into foolish denialism.

Denialism matters because all kinds of it have delayed our global political response to climate change by 30 years. In those critical decades since the 1980s, when humans first understood the urgency of the climate crisis, total historical carbon emissions since the industrial revolution have doubled . And still global emissions are rising, every year.

The physics of this process are inexorable – and so simple, as Greta would say, even a child can understand. We are already committing ourselves to two degrees of warming, possibly three or four. Denialists have, knowingly and with malice aforethought, condemned future generations to what Tim Flannery calls a “grim winnowing”. Flannery wrote recently “the climate crisis has now grown so severe that the actions of the denialists have turned predatory: they are now an immediate threat to our children.”

Read more: The gloves are off: 'predatory' climate deniers are a threat to our children

The history of denialism alerts us to a disastrous paradox: the very moment, in the 1980s, when it became clear global warming was a collective predicament of humanity, we turned away politically from the idea of the collective, with dire consequences. Naomi Klein, in her latest book On Fire , elucidates this fateful coincidence, which she calls “an epic case of historical bad timing”: just as the urgency of action on climate change became apparent, “the global neoliberal revolution went supernova”.

Unfettered free-market fanaticism and its relentless attack on the public sphere derailed the momentum building for corporate regulation and global cooperation. Ten years ago, thoughtful, informed climate activists could still argue that we can decouple the debates about economy and democracy from climate action. But now we can’t. At the 2019 election, Australia may have missed its last chance for incremental political change. If the far right had not politicised climate change and delayed action for so long then radical political transformation would not necessarily have been required. But now it will be, and it’s coming.

A great derangement

We are indeed living in what we might call “uncanny times”. They are weird, strange and unsettling in ways that question nature and culture and even the possibility of distinguishing between them.

The Bengali novelist Amitav Ghosh uses the term “uncanny” in his book The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable , published in 2016. The planet is alive, says Ghosh, and only for the last three centuries have we forgotten that. We have been suffering from “the great derangement”, a disturbing condition of wilful and systematic blindness to the consequences of our own actions, in which we are knowingly killing the planetary systems that support the survival of our species. That’s what’s uncanny about our times: we are half-aware of this predicament yet also paralysed by it, caught between horror and hubris.

We inhabit a critical moment in the history of the Earth and of life on this planet, and a most unusual one in terms of our own human history. We have developed two powerful metaphors for making sense of it. One is the idea of the Anthropocene , which is the insight we have entered a new geological epoch in the history of the Earth and have now left behind the 13,000 years of the relatively stable Holocene epoch, the period since the last great ice age. The new epoch recognises the power of humans in changing the nature of the planet, putting us on a par with other geophysical forces such as variations in the earth’s orbit, glaciers, volcanoes and asteroid strikes.

The other potent metaphor for this moment in Earth history is the Sixth Extinction . Humans have wiped out about two-thirds of the world’s wildlife in just the last half-century.

Let that sentence sink in. It has happened in less than a human lifetime. The current extinction rate is a hundred to a thousand times higher than was normal in nature. There have been other such catastrophic collapses in the diversity of life on Earth: five of them – sudden, shocking falls in the graph of biodiversity separated by tens of millions of years, the last one in the immediate aftermath of the asteroid impact that ended the age of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. We now have to ask ourselves: are we inhabiting – and causing – the Sixth Extinction?

These two metaphors – the Anthropocene and the Sixth Extinction – are both historical concepts that require us to travel in geological and biological time across hundreds of millions of years and then to arrive back at the present with a sense not of continuity but of discontinuity, of profound rupture. That’s what Earth system science has revealed: it’s now too late to go back to the Holocene. We’ve irrevocably changed the Earth system and unwittingly steered the planet into the Anthropocene; now we can’t take our hand off the tiller.

Earth is alive

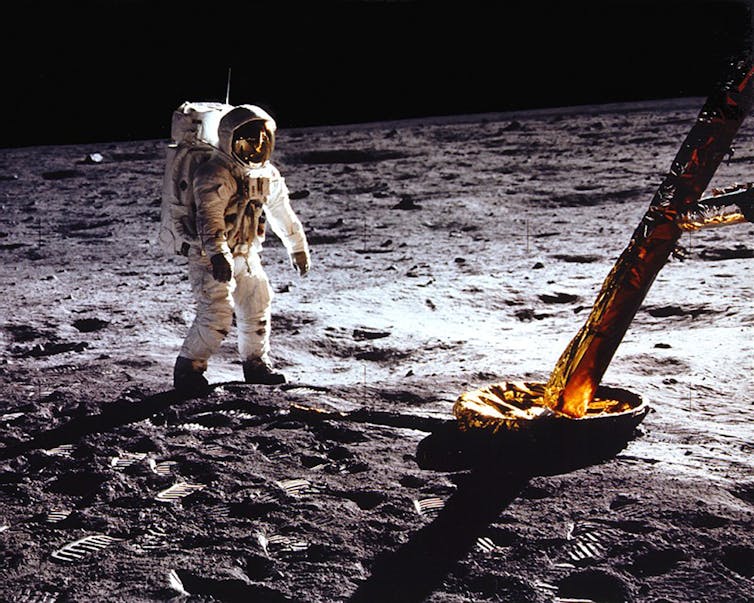

I’ve been considering metaphors of deep time, but what of deep space? It has also enlarged our imaginations in the last half century. In July this year, we commemorated the 50th anniversary of the Moon landing. I was 12 at the time of the Apollo 11 voyage and found myself in a school debate about whether the money for the Moon mission would be better spent on Earth. I argued it would be, and my team lost.

But what other result was allowable in July 1969? Conquering the Moon, declared Dr Wernher von Braun, Nazi scientist turned US rocket maestro, assured man of immortality . I followed the Apollo missions with a sense of wonder, staying up late to watch the Saturn V launch, joining my schoolmates in a large hall with tiny televisions to witness Armstrong take his Giant Leap, and saving full editions of The Age newspaper reporting those fabled days.

The rhetoric of space exploration was so future-oriented that NASA did not foresee Apollo’s greatest legacy: the radical effect of seeing the Earth. In 1968, the historic Apollo 8 mission launched humans beyond Earth’s orbit for the first time, into the gravitational power of another heavenly body. For three lunar orbits, the three astronauts studied the strange, desolate, cratered surface below them and then, as they came out from the dark side of the Moon for the fourth time, they looked up and gasped :

Frank Borman: Oh my God! Look at that picture over there! Here’s the Earth coming up. Wow, that is pretty! Bill Anders: Hey, don’t take that, it’s not scheduled.

They did take the unscheduled photo, excitedly, and it became famous, perhaps the most famous photograph of the 20th century, the blue planet floating alone, finite and vulnerable in space above a dead lunar landscape. Bill Anders declared : “We came all this way to explore the Moon, and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.”

In his fascinating book, Earthrise (2010), British historian Robert Poole explains this was not supposed to happen. The cutting edge of the future was to be in space. Leaving the Earth’s atmosphere was seen as a stage in human evolution comparable to our amphibian ancestor crawling out of the primeval slime onto land.

Furthermore, this new dominion was seen to offer what Neil Armstrong called a “survival possibility” for a world shadowed by the nuclear arms race. In the words of Buzz Lightyear (who is sometimes hilariously confused with Buzz Aldrin), the space age looked to infinity and beyond!

Earthrise had a profound impact on environmental politics and sensibilities. Within a few years, the American scientist James Lovelock put forward “ the Gaia hypothesis ”: that the Earth is a single, self-regulating organism. In the year of the Apollo 8 mission, Paul Ehrlich published his book, The Population Bomb , an urgent appraisal of a finite Earth. British economist Barbara Ward wrote Spaceship Earth and Only One Earth , revealing how economics failed to account for environmental damage and degradation, and arguing that exponential growth could not continue forever.

Earth Day was established in 1970, a day to honour the planet as a whole, a total environment needing protection. In 1972, the Club of Rome released its controversial and influential report The Limits to Growth , which sold over 13 million copies. In their report, Donella Meadows and Dennis Meadows wrestled with the contradiction of trying to force infinite material growth on a finite planet. The cover of their book depicted a whole Earth, a shrinking Earth.

Earth systems science developed in the second half of the 20th century and fostered a keen understanding of planetary boundaries – thresholds in planetary ecology - and the extent to which they were being violated. The same industrial capitalism that unleashed carbon enabled us to extract ice cores from the poles and construct a deep history of the air. The fossil fuels that got humans to the Moon, it now emerged, were endangering our civilisation.

The American ecologist and conservationist Aldo Leopold wrote in 1949 of the need for a new “land ethic” . Leopold envisaged a gradual historical expansion of human ethics, from the relations between individuals to those between the individual and society, and ultimately to those between humans and the land. He hoped for an enlargement of the community to which we imagine ourselves belonging, one that includes soil, water, plants and animals.

In his book of essays, A Sand County Almanac , there is a short, profound reflection called “Thinking like a mountain.” He tells of going on the mountain and shooting a wolf and her cubs and then watching “a fierce green fire” die in her eyes.

He shot her because he thought fewer wolves meant more deer, but over the years he watched the overpopulated deer herd die as the wolfless mountain became a dustbowl. Leopold came to understand the beautiful delicacy of the ecosystem, which holds “a deeper meaning, known only to the mountain itself. Only the mountain has lived long enough to listen objectively to the howl of a wolf.”

Today, 70 years after Leopold’s philosophical leap, we are being challenged to scale up from a land ethic to an earth ethic, to an environmental vision and philosophy of action that sees the planet as an integrated whole and all of life upon it as an interdependent historical community with a common destiny, to think not only like a mountain, but also like a planet. We are belatedly remembering the planet is alive.

Climate science is climate history

Climate change and ecological crisis are often seen as purely scientific issues. But as humanities scholars we know all environmental problems are at heart human ones; “scientific” issues are pre-eminently challenges for the humanities. Historical perspective can offer much in this time of ecological crisis, and many historians are reinventing their traditional scales of space and time to tell different kinds of stories, ones that recognise the agency of other creatures and the unruly power of nature.

There is a tendency among denialists to lazily use history against climate science, arguing for example “the climate’s always changing”, or “this has happened before”. Good recent historical scholarship about the last 2000 years of human civilisation is so important because it corrects these misunderstandings. That’s why it’s so disappointing when celebrity historians like Niall Ferguson and Geoffrey Blainey seek to represent their discipline by ignoring the work of their colleagues.

Climate science is unavoidably climate history; it’s an empirical, historical interpretation of life on earth, full of new insights into the impact and predicament of humanity in the long and short term. Recent histories of the last 2,000 years have been crucial in helping us to appreciate the fragile relationship between climate and society, and why future average temperature changes of more than 2°C can have dire consequences for human civilisation.

We now have environmental histories of antiquity, and of medieval and early modern Europe – studies casting new light on familiar human dramas, including the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, the Black Death in the medieval period, and the unholy trinity of famine, war and disease during the Little Ice Age of the 17th century.

These books draw on natural as well as human history, on the archives of ice, air and sediment as well as bones, artefacts and documents. And then there is John McNeill’s history of the 20th century, Something New Under the Sun , which argues “the human race, without intending anything of the sort, has undertaken a gigantic uncontrolled experiment on earth”.

These new histories encompass the planet and the human species, and provocatively blur biological evolution and cultural history (Yuval Noah Harari’s “brief history of humankind”, Sapiens , is a bestselling example). They investigate the vast elemental nature of the heavens as well as the interior, microbial nature of human bodies: nature inside and out, with the striving human as a porous vessel for its agency.

In Australia, we have outstanding new histories linking geological and human time, such as Charles Massy’s Call of the Reed Warbler: A New Agriculture – A New Earth and Tony Hughes d’Aeth’s Like Nothing on This Earth: A Literary History of the Wheatbelt .

Australians seem predisposed to navigate the Anthropocene. I think it’s because the challenge of Australian history in the 21st century is how to negotiate the rupture of 1788, how to relate geological and human scales, how to get our heads and hearts around a colonial history of 200 years that plays out across a vast Indigenous history in deep time.

From the beginnings of colonisation, Australia’s new arrivals commonly alleged Aboriginal people had no history, had been here no more than a few thousand years, and were caught in the fatal thrall of a continental museum. But from the early 1960s, archaeologists confirmed what Aboriginal people had always known: Australia’s human history went back aeons, into the Pleistocene, well into the last ice age. In the late 20th century, the timescale of Australia’s human history increased tenfold in just 30 years and the journey to the other side of the frontier became a journey back into deep time.

Read more: Friday essay: when did Australia’s human history begin?

It’s no wonder the idea of big history was born here, or environmental history has been so innovative here. This is a land of a radically different ecology, where climatic variation and uncertainty have long been the norm – and are now intensifying. Australia’s long human history spans great climatic change and also offers a parable of cultural resilience.

Even the best northern-hemisphere scholars struggle to digest the implications of the Australian time revolution. They often assume, for example, “civilisation” is a term associated only with agriculture, and still insist 50,000 years is a possible horizon for modern humanity. Australia offers a distinctive and remarkable human saga for a world trying to come to terms with climate change and the rupture of the Anthropocene. Living on a precipice of deep time has become, I think, an exhilarating dimension of what it means to be Australian. Our nation’s obligation to honour the Uluru Statement is not just political; it is also metaphysical. It respects another ethical practice and another way of knowing.

Earthspeaking

In 2003, in its second issue, Griffith Review put the land at the centre of the nation. The edition was called Dreams of Land and it’s full of gold, including an essay by Ian Lowe sounding the alarm on the ecological and climate emergency – which reminds us how long we’ve had these eloquent warnings. As Graeme Davison said on launching the edition in December 2003:

At the threshold of the 21st century Australia has suddenly come down to earth. […] Earth, water, wind and fire are not just natural elements; they are increasingly the great issues of the day.

It is instructive to compare this issue of the Griffith Review, with the edition entitled Writing the Country , published 15 years later last summer. In the intervening decade and a half, sustainability morphed into survival, native title into Treaty and the Voice, the Anthropocene infiltrated our common vocabulary, the republic and Aboriginal recognition are no longer separable, and land decisively became Country with a capital “C”. In 2003 the reform hopes of the 1990s had not entirely died, but by 2019 it’s clear the dead hand of the Howard government and its successors has thoroughly throttled trust in the workings of the state.

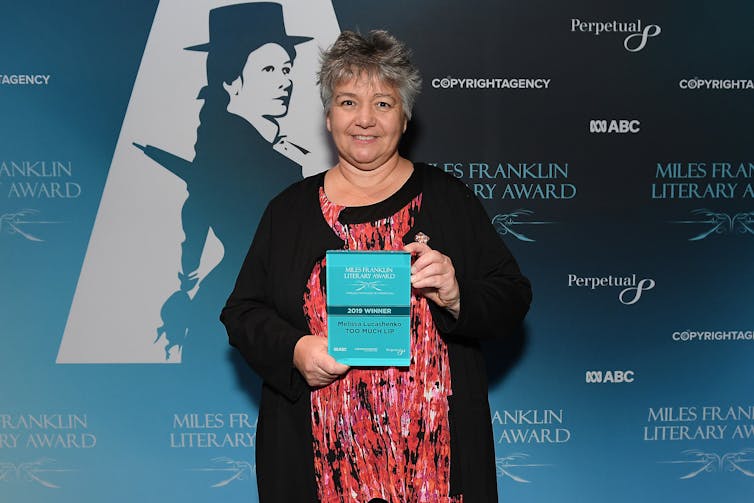

Perhaps the most powerful contribution in GR2 – and it was given the honour of appearing first – was an essay by Melissa Lucashenko called “Not quite white in the head”. This year’s Miles Franklin winner, Lucashenko was already in great form in 2003. Tough, poetic and confronting, the words of her essay still resonate. Lucashenko writes of “earthspeaking”.

“I am earthspeaking,” she says, “talking about this place, my home and it is first, a very small story […] This earthspeaking is a small, quiet story in a human mouth.”

“Big stories are failing us as a nation,” suggests Lucashenko. “But we are citizens and inheritors and custodians of tiny landscapes too. It is the small stories that attach to these places […] which might help us find a way through.”

I think earthspeaking is a companion to thinking like a planet. Instead of beginning from the outside with a view of Earth in deep space and deep time, earthspeaking works from the ground up; it is inside-out; it begins with beloved Country. So it is with earthspeaking I want to finish.

Four months ago I was privileged to sit in a circle with Mithaka people, the traditional Aboriginal owners of 33,000 square kilometres of the Kirrenderi/Channel Country of the Lake Eyre Basin in south-western Queensland. In 2015, the Federal Court handed down a native title consent determination for the Mithaka enabling them to return to Country. Now they have begun a process of assessing and renewing their knowledge.

I was invited to be involved because I have studied the major white writer about this region, a woman called Alice Duncan-Kemp who was born on this land in 1901 where her family ran a cattle farm, and grew up with Mithaka people who worked on the station and were her carers and teachers. Young Alice spent her childhood days with her Aboriginal friends and teachers, especially Mary Ann and Moses Youlpee, who took her on walks and taught her the names and meanings and stories that connected every tree, bird, plant, animal, rock, dune and channel.

From the 1930s to the 1960s Alice wrote four books – half a million words – about the world of her childhood and the people and nature of the Channel Country, and although she did find a wide readership, her books were dismissed by authorities, landowners and locals as “romantic” and “nostalgic” and “fictional”.

Her writing was systematically marginalised: she was a woman in cattle country, a sympathiser with Aboriginal people, she refused to ignore the violence of the frontier and she challenged the typical heroic western style of narrative. The huge Kidman pastoral company bought her family’s land in 1998, bulldozed the historic pisé homestead into the creek, threw out the collection of Aboriginal artefacts, and continues to deny Alice’s writings have any historical authenticity. Yet her books were respected in the native title process and were crucial to the Mithaka in their fight to regain access to Country.

It was very moving to be present this year when Alice’s descendants and Moses’ people met for the first time. It was not just a social and symbolic occasion: we had come together as researchers and we had work to do. Across a weekend we pored over maps and talked through evidence, combining legend, memory, oral history, letters and manuscripts, published books, archaeological studies, surveyors’ records, and even recent drone footage of the remote terrain, all with the purpose of retrieving and reactivating knowledge, recovering language and reanimating Country. We could literally map Alice’s stories back onto features of the land, with the aim of bringing it under caring attention again.

This process is going on in beloved places right across the continent. Grace Karskens and Kim Mahood write beautifully in GR63 about similar quests, and of their hope written words dredged from the archive “might again be spoken as part of living language and shared geographies.”

Earthspeaking and thinking like a planet are profoundly linked. As the Indigenous speaker at the Melbourne Climate Strike said, “We stand for you when we stand for Country.” In these frightening and challenging times, we need radical storytelling and scholarly histories, narratives that weave together humans and nature, history and natural history, that move from Earth systems to the earth beneath our feet, from the lonely, living planet spinning through space to the intimately known and beloved local worlds over which we might, if we are lucky, exert some benevolent influence.

We need them not only because they help us to better understand our predicament, but also because they might enable us to act, with intelligence and grace.

This essay was adapted from the Showcase Lecture, Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research, Griffith University, Queensland, Wednesday, 9 October 2019

- Climate change

- Anthropocene

- Friday essay

- Environmental history

- Greta Thunberg

- Extinction Rebellion

- Extinction crisis

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Data and Reporting Analyst

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

How the climate crisis is already harming America – photo essay

The damage rising temperatures bring is been seen around the country, with experts fearing worse is to come

C limate change is not an abstract future threat to the United States, but a real danger that is already harming Americans’ lives, with “substantial damages” to follow if rising temperatures are not controlled.

This was the verdict of a major US government report two years ago. The Trump administration’s attitude to climate change was perhaps illustrated in the timing of the report’s release, which was in the news dead zone a day after Thanksgiving.

The report was the fourth National Climate Assessment (NCA), and is seen as the most authoritative official US snapshot of the impacts of climate change being seen already, and the estimate of those in the future.

It is the combined work of 13 federal agencies, and it warns how climate-related threats to Americans’ physical, social and economic wellbeing are rising, and will continue to grow without additional action.

Here we look at the regions of the US where it describes various impacts, with photography from these areas showing people and places in the US where climate change is very real.

Alaska – unpredictable weather

If there was a ground zero for the climate crisis in the US, it would probably be located in Alaska. The state, according to the national climate assessment, is “ on the front lines of climate change and is among the fastest warming regions on Earth”.

Since the early 1980s, Alaska’s sea ice extent in September, when it hits its annual minimum, has decreased by as much as 15% per decade, with sea ice-free summers likely this century. This has upended fishing routines for remote communities that rely upon caught fish for their food.

The thinning ice has seen people and vehicles collapse into the frigid water below, hampering transport routes. Roads and buildings have buckled as the frozen soils underneath melt. Wildfires are also an increasing menace in Alaska, with three out of the top four fire years in terms of acres burned occurring since 2000. The state’s residents are grappling with a rapidly changing environment that is harming their health, their supply of food and livelihoods.

Last year was the hottest year on record in Alaska , 6.2F warmer than the long-term average.

North-east – snowstorms, drought, heatwaves and flooding

The north-east, home to a sizable chunk of the US population and marked by hot summers and cold, snowy winters, is undergoing a major climatic upheaval.

The most rapidly warming region of the contiguous United States, the north-east is set to be, on average, 2C warmer than the pre-industrial era by 2035, decades before the the global average reaches this mark.

These rising temperatures are bringing punishing heatwaves, coastal flooding and more intense rainfall. Snow storms may decrease in number but increase in intensity, while the warming oceans are already altering the composition of available seafood – lobsters, for example, are fleeing north to the cooler waters of Maine and Canada.

High-tide flooding will soak about 20 north-east cities for at least 30 days a year by 2050, scientists predict, with the region also hit by stronger hurricanes and storms. These changes will “threaten the sustainability of communities and their livelihoods”, the national climate assessment warns.

A major challenge for the north-east will be adaptation to this hotter, more turbulent world. As home to some of America’s oldest cities, such as New York and Philadelphia, the region has plenty of ageing, inefficient housing that ill-equipped to deal with extreme heat.

Northern Great Plains – flash droughts and extreme heat

Water is the crucial issue in the northern Great Plains, a vital resource largely provided by the gradual melting of snowpack that builds up in the colder months.

Rising temperatures are set to increase the number of heatwaves and accelerate the melt of snow, leading to droughts. At the same time, rainfall intensity is growing, with downpours in winter and spring to increase by up to a third by the end of the century.

This is set to lead to a see-sawing effect where severe droughts will be interspersed by flooding, a scenario that played out in 2011, when major floods were followed by drought in 2012. This, the national assessment states, represents a “new and unprecedented variability that is likely to become more common in a warmer world”.

Midwest – heavy rains and soil erosion

The US midwest, home to 60 million people, is the agricultural heartland of the country, growing the bulk of corn, soy and other commodity crops produced on US soil.

The climate crisis is starting to play havoc with established farming routines, however, with increasing heat and pounding rainfall causing the erosion of soils and introduction of harmful pests and diseases. Overall yields are set to drop, with the productivity of the midwest set to drop back to 1980s levels by mid-century.