- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Social Media Is a Threat to Privacy, Essay Example

Pages: 3

Words: 860

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

Introduction

Social networking has been a global phenomenon with the proliferation of various social networking platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. In many ways, social media has replaced conventional modes of communication such as the telephone and email. People can keep in touch with others by sharing experiences and photographs, and most cases exchange personal information. Social media users usually post private information as part of the process of knowing one another. Since social media is associated with having a large number of users unknown to the client, there is an increased risk of exposing personal details to cybercriminals.

Social media is a threat to privacy

Social media has increased privacy concerns with online platforms. Although they are effective in connecting with family and friend, social media can also endanger private information. Individuals create social media profiles that may expose their private information. According to research conducted by Carnegie Mellon University, information found in social media is sufficient to guess one’s social security number, which can lead to identity theft. With the advent of mobile banking applications, more people are login their sensitive data to smartphones, which can endanger their privacy.

Another group whose privacy is in danger is teenagers. Teenagers post a significant amount of information online, which makes it vitally for them to understand the people they share information with or use privacy settings. However, most teenagers are interested with capturing the attention of their peers and in the process posting information that may enhance their status. This information may not seem harmful, but it can be exploited by cyber criminals to get access to the parents.

Several articles have argued about the threat of privacy in online platforms such as social media. In “online privacy: current health 2 by given (2009),” the author argues that online predators can figure out information posted in online platforms, which can be used against the user. Additionally, employers can use the online platform to check out their employees. With the proliferation of electronic health registers, cyber criminals can access an individual’s health information. It presents a significant danger to the individuals concerned because such registers contain vital information such as social security number and insurance details.

In her article titled” should you panic about online privacy?” Palmer (2010) notes that online platforms are a threat to privacy and individual must take measures to protect their personal data. Due to the threat posed by online environments to privacy, Palmer suggests various strategies that user can use to safeguard their privacy. One way of doing this is by removing the birth year from a personal profile in social media networks because the full birth year is often used by banks to categorize their clients. Cyber criminals can use such information to access online banking systems that can compromise user’s safety. Another suggestion given by Palmer is to use antivirus and anti-spyware. These techniques will prevent criminals from exploiting them to access confidential information.

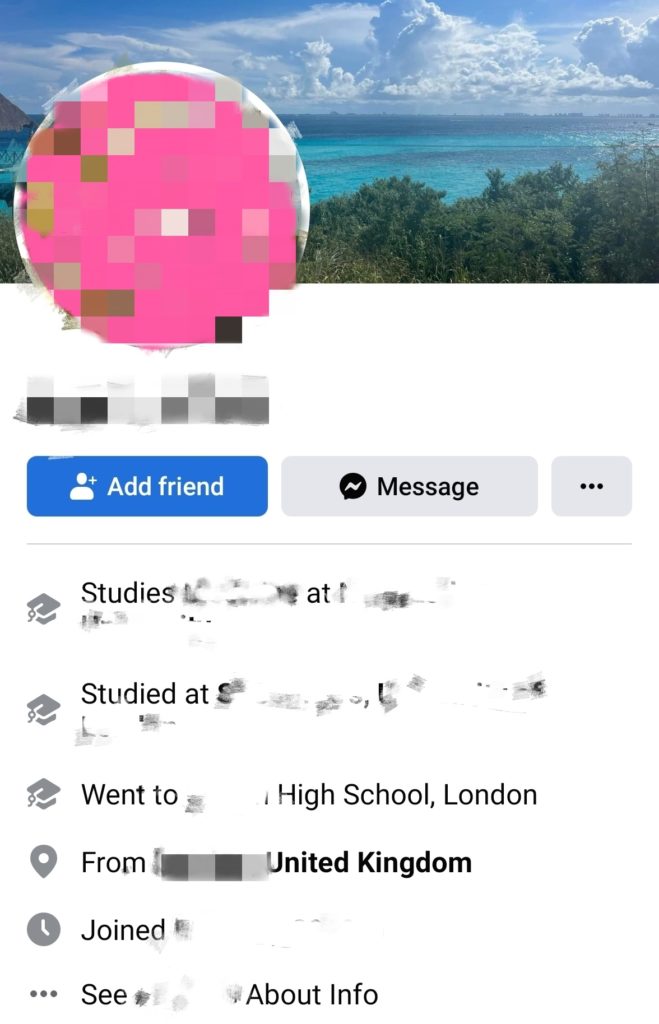

In the piece carried by the New Yorker tiled “the face of Facebook” by José Vargas may present information about Mark Zuckerberg that is public domain, it illustrates how Facebook profiles reveal private and confidential information to virtually anyone on the site. FACEBOOK is a directory of global citizens that affords people the chance to create public identities. Friends can access this information; friends of friends can also access some while some information is also available to anyone interested in them. Although the company has changed it privacy policies severally, it still exposes private information in several ways. From Zuckerberg’s profile, it is possible to know that he has three sisters, where he schooled in, he favorite comedian and musicians, and his interests. His friends can also access his cell-phone number and email address. Additionally, the addition of a feature known as Places, which allows users to mark their location means that someone interested in Zuckerberg’s location can know it anytime. The article by Vargas reveals how easy it is to access one’s private information in Facebook.

Plagiarism, which is using another person’s ideas or creations without giving credit to that person, is another concern in social media. Individuals take information from other sources or individuals and use them as their own, which a common practice in social media. The lack of attribution and fabrication of content are the real issues because users seldom give credit to the source of the content. Despite the fact that social media is for connecting with friends and family, it has been used as social aggregators, which makes it important to give links to the sources of the content.

Social media platforms raise concerns over privacy issues because others can exploit information that is innocently posted on these sites. Cyber criminals can exploit the information to harm the user. It is important to note that different people can access information posted online. Users must take significant steps to protect their information by using anti-spyware software and emitting sensitive information in their profiles.

Given M. (2008). online privacy. Current health 2 . Retrieved from academic search complete.

Palmer L. (2010, 08) should you panic about online privacy? Redbook , Vol. 215 Issue 2, p130

Vargas,J.A. ( 2010, sep20). The face of Facebook. The New Yorker. Retrieved from http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/09/20/the-face-of-facebook

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Vitamin C Experiment, Essay Example

The Professionalization of Ujwai Bharati, Essay Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

Read our research on: Gun Policy | International Conflict | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Americans’ complicated feelings about social media in an era of privacy concerns.

Amid public concerns over Cambridge Analytica’s use of Facebook data and a subsequent movement to encourage users to abandon Facebook , there is a renewed focus on how social media companies collect personal information and make it available to marketers.

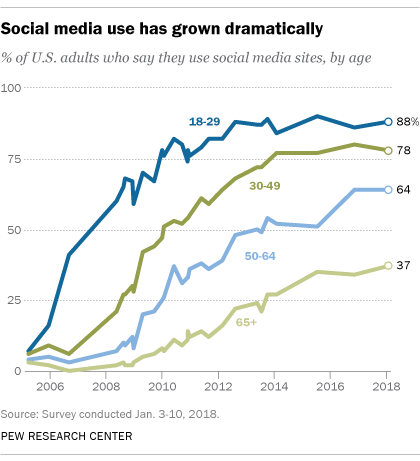

Pew Research Center has studied the spread and impact of social media since 2005, when just 5% of American adults used the platforms. The trends tracked by our data tell a complex story that is full of conflicting pressures. On one hand, the rapid growth of the platforms is testimony to their appeal to online Americans. On the other, this widespread use has been accompanied by rising user concerns about privacy and social media firms’ capacity to protect their data.

All this adds up to a mixed picture about how Americans feel about social media. Here are some of the dynamics.

People like and use social media for several reasons

The Center’s polls have found over the years that people use social media for important social interactions like staying in touch with friends and family and reconnecting with old acquaintances. Teenagers are especially likely to report that social media are important to their friendships and, at times, their romantic relationships .

Beyond that, we have documented how social media play a role in the way people participate in civic and political activities, launch and sustain protests , get and share health information , gather scientific information , engage in family matters , perform job-related activities and get news . Indeed, social media is now just as common a pathway to news for people as going directly to a news organization website or app.

Our research has not established a causal relationship between people’s use of social media and their well-being. But in a 2011 report, we noted modest associations between people’s social media use and higher levels of trust, larger numbers of close friends, greater amounts of social support and higher levels of civic participation.

People worry about privacy and the use of their personal information

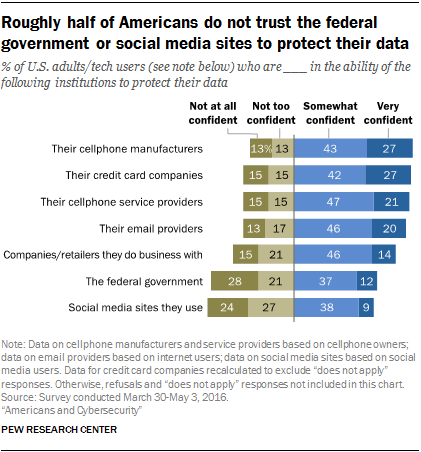

While there is evidence that social media works in some important ways for people, Pew Research Center studies have shown that people are anxious about all the personal information that is collected and shared and the security of their data.

Overall, a 2014 survey found that 91% of Americans “agree” or “strongly agree” that people have lost control over how personal information is collected and used by all kinds of entities. Some 80% of social media users said they were concerned about advertisers and businesses accessing the data they share on social media platforms, and 64% said the government should do more to regulate advertisers.

Moreover, people struggle to understand the nature and scope of the data collected about them. Just 9% believe they have “a lot of control” over the information that is collected about them, even as the vast majority (74%) say it is very important to them to be in control of who can get information about them.

Six-in-ten Americans (61%) have said they would like to do more to protect their privacy. Additionally, two-thirds have said current laws are not good enough in protecting people’s privacy, and 64% support more regulation of advertisers.

Some privacy advocates hope that the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation , which goes into effect on May 25, will give users – even Americans – greater protections about what data tech firms can collect, how the data can be used, and how consumers can be given more opportunities to see what is happening with their information.

People’s issues with the social media experience go beyond privacy

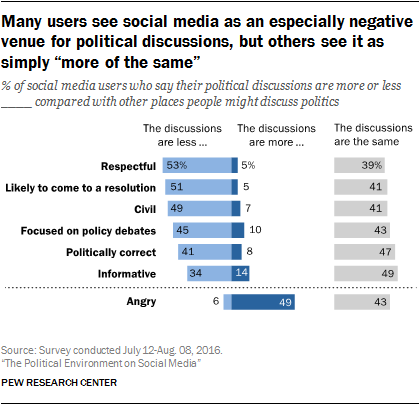

In addition to the concerns about privacy and social media platforms uncovered in our surveys, related research shows that just 5% of social media users trust the information that comes to them via the platforms “a lot.”

A considerable number of social media users said they simply ignored political arguments when they broke out in their feeds. Others went steps further by blocking or unfriending those who offended or bugged them.

Why do people leave or stay on social media platforms?

The paradox is that people use social media platforms even as they express great concern about the privacy implications of doing so – and the social woes they encounter. The Center’s most recent survey about social media found that 59% of users said it would not be difficult to give up these sites, yet the share saying these sites would be hard to give up grew 12 percentage points from early 2014.

Some of the answers about why people stay on social media could tie to our findings about how people adjust their behavior on the sites and online, depending on personal and political circumstances. For instance, in a 2012 report we found that 61% of Facebook users said they had taken a break from using the platform. Among the reasons people cited were that they were too busy to use the platform, they lost interest, they thought it was a waste of time and that it was filled with too much drama, gossip or conflict.

In other words, participation on the sites for many people is not an all-or-nothing proposition.

People pursue strategies to try to avoid problems on social media and the internet overall. Fully 86% of internet users said in 2012 they had taken steps to try to be anonymous online. “Hiding from advertisers” was relatively high on the list of those they wanted to avoid.

Many social media users fine-tune their behavior to try to make things less challenging or unsettling on the sites, including changing their privacy settings and restricting access to their profiles. Still, 48% of social media users reported in a 2012 survey they have difficulty managing their privacy controls.

After National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden disclosed details about government surveillance programs starting in 2013, 30% of adults said they took steps to hide or shield their information and 22% reported they had changed their online behavior in order to minimize detection.

One other argument that some experts make in Pew Research Center canvassings about the future is that people often find it hard to disconnect because so much of modern life takes place on social media. These experts believe that unplugging is hard because social media and other technology affordances make life convenient and because the platforms offer a very efficient, compelling way for users to stay connected to the people and organizations that matter to them.

Note: See topline results for overall social media user data here (PDF).

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

Social Media Fact Sheet

7 facts about americans and instagram, social media use in 2021, 64% of americans say social media have a mostly negative effect on the way things are going in the u.s. today, share of u.s. adults using social media, including facebook, is mostly unchanged since 2018, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

- Search Search for:

- News & Stories

The Erosion of Privacy: Social Media’s Impact on Personal Information

Social media has become an integral part of our lives in digital age, providing a platform for sharing experiences, opinions, and personal information. However, this convenience comes with a price – the erosion of our privacy. Social media encourages users to share vast amounts of personal information , often without fully understanding the implications.

The impact of personal information leakage on social media is far-reaching and can have significant consequences. Take Zoey He, for example, a former online celebrity with a considerable following. As her popularity grew, she found herself grappling with the distress caused by the interconnectivity of information across multiple platforms. What started as sharing her daily life on Instagram soon spilled over to Facebook and other platforms, making her feel like her personal space was invaded.

As Zoey gained more followers, she faced escalating consequences. Among them, the most concerning was when she shared a video about her job, and someone cleverly gain information from it and find her LinkedIn profile, leading to emailed her working company based on what she accidentally said about her work . This intrusion into her professional life had detrimental effects on her work. This incident led her to a realization: “I came to understand that finding a balance between personal sharing and privacy protection on social media is a challenge.” To protect herself, Zoey gave up on becoming an influencer, made her account private, and only shared updates with close friends.

Social media platforms thrive on user engagement and data-driven business models. They entice users to disclose personal details through various means, such as prompts to complete profiles, sharing location, and interactions with friends and family. The more information shared, the better platforms can tailor content and advertisements, creating an addictive user experience.

Join us on a journey to unravel the reasoning behind social media’s user data collection as we delve into a conversation with business expert, Pham Thanh Thao (who worked as Research Manager at NielsenIQ) . Get ready to gain valuable insights from her perspective on this intricate topic.

Disclaimer:

This website is part of a student project. While the information on this website has been verified to the best of our abilities, we cannot guarantee that there are no mistakes or errors.

The material on this site is given for general information only and does not constitute professional advice.

The views expressed through this site are those of the individual contributors and not those of the website owner. We are not responsible for the content of external sites.

I have no idea how to avoid privacy disclosure

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Why protecting privacy is a losing game today—and how to change the game

Subscribe to techstream, cameron f. kerry cameron f. kerry ann r. and andrew h. tisch distinguished visiting fellow - governance studies , center for technology innovation @cam_kerry.

July 12, 2018

Recent congressional hearings and data breaches have prompted more legislators and business leaders to say the time for broad federal privacy legislation has come. Cameron Kerry presents the case for adoption of a baseline framework to protect consumer privacy in the U.S.

Kerry explores a growing gap between existing laws and an information Big Bang that is eroding trust. He suggests that recent privacy bills have not been ambitious enough, and points to the Obama administration’s Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights as a blueprint for future legislation. Kerry considers ways to improve that proposal, including an overarching “golden rule of privacy” to ensure people can trust that data about them is handled in ways consistent with their interests and the circumstances in which it was collected.

Table of Contents Introduction: Game change? How current law is falling behind Shaping laws capable of keeping up

- 31 min read

Introduction: Game change?

There is a classic episode of the show “I Love Lucy” in which Lucy goes to work wrapping candies on an assembly line . The line keeps speeding up with the candies coming closer together and, as they keep getting farther and farther behind, Lucy and her sidekick Ethel scramble harder and harder to keep up. “I think we’re fighting a losing game,” Lucy says.

This is where we are with data privacy in America today. More and more data about each of us is being generated faster and faster from more and more devices, and we can’t keep up. It’s a losing game both for individuals and for our legal system. If we don’t change the rules of the game soon, it will turn into a losing game for our economy and society.

More and more data about each of us is being generated faster and faster from more and more devices, and we can’t keep up. It’s a losing game both for individuals and for our legal system.

The Cambridge Analytica drama has been the latest in a series of eruptions that have caught peoples’ attention in ways that a steady stream of data breaches and misuses of data have not.

The first of these shocks was the Snowden revelations in 2013. These made for long-running and headline-grabbing stories that shined light on the amount of information about us that can end up in unexpected places. The disclosures also raised awareness of how much can be learned from such data (“we kill people based on metadata,” former NSA and CIA Director Michael Hayden said ).

The aftershocks were felt not only by the government, but also by American companies, especially those whose names and logos showed up in Snowden news stories. They faced suspicion from customers at home and market resistance from customers overseas. To rebuild trust, they pushed to disclose more about the volume of surveillance demands and for changes in surveillance laws. Apple, Microsoft, and Yahoo all engaged in public legal battles with the U.S. government.

Then came last year’s Equifax breach that compromised identity information of almost 146 million Americans. It was not bigger than some of the lengthy roster of data breaches that preceded it, but it hit harder because it rippled through the financial system and affected individual consumers who never did business with Equifax directly but nevertheless had to deal with the impact of its credit scores on economic life. For these people, the breach was another demonstration of how much important data about them moves around without their control, but with an impact on their lives.

Now the Cambridge Analytica stories have unleashed even more intense public attention, complete with live network TV cut-ins to Mark Zuckerberg’s congressional testimony. Not only were many of the people whose data was collected surprised that a company they never heard of got so much personal information, but the Cambridge Analytica story touches on all the controversies roiling around the role of social media in the cataclysm of the 2016 presidential election. Facebook estimates that Cambridge Analytica was able to leverage its “academic” research into data on some 87 million Americans (while before the 2016 election Cambridge Analytica’s CEO Alexander Nix boasted of having profiles with 5,000 data points on 220 million Americans). With over two billion Facebook users worldwide, a lot of people have a stake in this issue and, like the Snowden stories, it is getting intense attention around the globe, as demonstrated by Mark Zuckerberg taking his legislative testimony on the road to the European Parliament .

The Snowden stories forced substantive changes to surveillance with enactment of U.S. legislation curtailing telephone metadata collection and increased transparency and safeguards in intelligence collection. Will all the hearings and public attention on Equifax and Cambridge Analytica bring analogous changes to the commercial sector in America?

I certainly hope so. I led the Obama administration task force that developed the “ Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights ” issued by the White House in 2012 with support from both businesses and privacy advocates, and then drafted legislation to put this bill of rights into law. The legislative proposal issued after I left the government did not get much traction, so this initiative remains unfinished business.

The Cambridge Analytica stories have spawned fresh calls for some federal privacy legislation from members of Congress in both parties, editorial boards, and commentators. With their marquee Zuckerberg hearings behind them, senators and congressmen are moving on to think about what do next. Some have already introduced bills and others are thinking about what privacy proposals might look like. The op-eds and Twitter threads on what to do have flowed. Various groups in Washington have been convening to develop proposals for legislation.

This time, proposals may land on more fertile ground. The chair of the Senate Commerce Committee, John Thune (R-SD) said “many of my colleagues on both sides of the aisle have been willing to defer to tech companies’ efforts to regulate themselves, but this may be changing.” A number of companies have been increasingly open to a discussion of a basic federal privacy law. Most notably, Zuckerberg told CNN “I’m not sure we shouldn’t be regulated,” and Apple’s Tim Cook expressed his emphatic belief that self-regulation is no longer viable.

For a while now, events have been changing the way that business interests view the prospect of federal privacy legislation.

This is not just about damage control or accommodation to “techlash” and consumer frustration. For a while now, events have been changing the way that business interests view the prospect of federal privacy legislation. An increasing spread of state legislation on net neutrality, drones, educational technology, license plate readers, and other subjects and, especially broad new legislation in California pre-empting a ballot initiative, have made the possibility of a single set of federal rules across all 50 states look attractive. For multinational companies that have spent two years gearing up for compliance with the new data protection law that has now taken effect in the EU, dealing with a comprehensive U.S. law no longer looks as daunting. And more companies are seeing value in a common baseline that can provide people with reassurance about how their data is handled and protected against outliers and outlaws.

This change in the corporate sector opens the possibility that these interests can converge with those of privacy advocates in comprehensive federal legislation that provides effective protections for consumers. Trade-offs to get consistent federal rules that preempt some strong state laws and remedies will be difficult, but with a strong enough federal baseline, action can be achievable.

how current law is falling behind

Snowden, Equifax, and Cambridge Analytica provide three conspicuous reasons to take action. There are really quintillions of reasons. That’s how fast IBM estimates we are generating digital information, quintillions of bytes of data every day—a number followed by 30 zeros. This explosion is generated by the doubling of computer processing power every 18-24 months that has driven growth in information technology throughout the computer age, now compounded by the billions of devices that collect and transmit data, storage devices and data centers that make it cheaper and easier to keep the data from these devices, greater bandwidth to move that data faster, and more powerful and sophisticated software to extract information from this mass of data. All this is both enabled and magnified by the singularity of network effects—the value that is added by being connected to others in a network—in ways we are still learning.

This information Big Bang is doubling the volume of digital information in the world every two years. The data explosion that has put privacy and security in the spotlight will accelerate. Futurists and business forecasters debate just how many tens of billions of devices will be connected in the coming decades, but the order of magnitude is unmistakable—and staggering in its impact on the quantity and speed of bits of information moving around the globe. The pace of change is dizzying, and it will get even faster—far more dizzying than Lucy’s assembly line.

Most recent proposals for privacy legislation aim at slices of the issues this explosion presents. The Equifax breach produced legislation aimed at data brokers. Responses to the role of Facebook and Twitter in public debate have focused on political ad disclosure, what to do about bots, or limits to online tracking for ads. Most state legislation has targeted specific topics like use of data from ed-tech products, access to social media accounts by employers, and privacy protections from drones and license-plate readers. Facebook’s simplification and expansion of its privacy controls and recent federal privacy bills in reaction to events focus on increasing transparency and consumer choice. So does the newly enacted California Privacy Act.

This information Big Bang is doubling the volume of digital information in the world every two years. The data explosion that has put privacy and security in the spotlight will accelerate. Most recent proposals for privacy legislation aim at slices of the issues this explosion presents.

Measures like these double down on the existing American privacy regime. The trouble is, this system cannot keep pace with the explosion of digital information, and the pervasiveness of this information has undermined key premises of these laws in ways that are increasingly glaring. Our current laws were designed to address collection and storage of structured data by government, business, and other organizations and are busting at the seams in a world where we are all connected and constantly sharing. It is time for a more comprehensive and ambitious approach. We need to think bigger, or we will continue to play a losing game.

Our existing laws developed as a series of responses to specific concerns, a checkerboard of federal and state laws, common law jurisprudence, and public and private enforcement that has built up over more than a century. It began with the famous Harvard Law Review article by (later) Justice Louis Brandeis and his law partner Samuel Warren in 1890 that provided a foundation for case law and state statutes for much of the 20th Century, much of which addressed the impact of mass media on individuals who wanted, as Warren and Brandeis put it, “to be let alone.” The advent of mainframe computers saw the first data privacy laws adopted in 1974 to address the power of information in the hands of big institutions like banks and government: the federal Fair Credit Reporting Act that gives us access to information on credit reports and the Privacy Act that governs federal agencies. Today, our checkerboard of privacy and data security laws covers data that concerns people the most. These include health data, genetic information, student records and information pertaining to children in general, financial information, and electronic communications (with differing rules for telecommunications carriers, cable providers, and emails).

Outside of these specific sectors is not a completely lawless zone. With Alabama adopting a law last April, all 50 states now have laws requiring notification of data breaches (with variations in who has to be notified, how quickly, and in what circumstances). By making organizations focus on personal data and how they protect it, reinforced by exposure to public and private enforcement litigation, these laws have had a significant impact on privacy and security practices. In addition, since 2003, the Federal Trade Commission—under both Republican and Democratic majorities—has used its enforcement authority to regulate unfair and deceptive commercial practices and to police unreasonable privacy and information security practices. This enforcement, mirrored by many state attorneys general, has relied primarily on deceptiveness, based on failures to live up to privacy policies and other privacy promises.

These levers of enforcement in specific cases, as well as public exposure, can be powerful tools to protect privacy. But, in a world of technology that operates on a massive scale moving fast and doing things because one can, reacting to particular abuses after-the-fact does not provide enough guardrails.

As the data universe keeps expanding, more and more of it falls outside the various specific laws on the books. This includes most of the data we generate through such widespread uses as web searches, social media, e-commerce, and smartphone apps. The changes come faster than legislation or regulatory rules can adapt, and they erase the sectoral boundaries that have defined our privacy laws. Take my smart watch, for one example: data it generates about my heart rate and activity is covered by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) if it is shared with my doctor, but not when it goes to fitness apps like Strava (where I can compare my performance with my peers). Either way, it is the same data, just as sensitive to me and just as much of a risk in the wrong hands.

As the data universe keeps expanding, more and more of it falls outside the various specific laws on the books.

It makes little sense that protection of data should depend entirely on who happens to hold it. This arbitrariness will spread as more and more connected devices are embedded in everything from clothing to cars to home appliances to street furniture. Add to that striking changes in patterns of business integration and innovation—traditional telephone providers like Verizon and AT&T are entering entertainment, while startups launch into the provinces of financial institutions like currency trading and credit and all kinds of enterprises compete for space in the autonomous vehicle ecosystem—and the sectoral boundaries that have defined U.S. privacy protection cease to make any sense.

Putting so much data into so many hands also is changing the nature of information that is protected as private. To most people, “personal information” means information like social security numbers, account numbers, and other information that is unique to them. U.S. privacy laws reflect this conception by aiming at “personally identifiable information,” but data scientists have repeatedly demonstrated that this focus can be too narrow. The aggregation and correlation of data from various sources make it increasingly possible to link supposedly anonymous information to specific individuals and to infer characteristics and information about them. The result is that today, a widening range of data has the potential to be personal information, i.e. to identify us uniquely. Few laws or regulations address this new reality.

Nowadays, almost every aspect of our lives is in the hands of some third party somewhere. This challenges judgments about “expectations of privacy” that have been a major premise for defining the scope of privacy protection. These judgments present binary choices: if private information is somehow public or in the hands of a third party, people often are deemed to have no expectation of privacy. This is particularly true when it comes to government access to information—emails, for example, are nominally less protected under our laws once they have been stored 180 days or more, and articles and activities in plain sight are considered categorically available to government authorities. But the concept also gets applied to commercial data in terms and conditions of service and to scraping of information on public websites, for two examples.

As more devices and sensors are deployed in the environments we pass through as we carry on our days, privacy will become impossible if we are deemed to have surrendered our privacy simply by going about the world or sharing it with any other person. Plenty of people have said privacy is dead, starting most famously with Sun Microsystems’ Scott McNealy back in the 20th century (“you have zero privacy … get over it”) and echoed by a chorus of despairing writers since then. Without normative rules to provide a more constant anchor than shifting expectations, true privacy actually could be dead or dying. The Supreme Court may have something to say on the subject in we will need a broader set of norms to protect privacy in settings that have been considered public. Privacy can endure, but it needs a more enduring foundation.

The Supreme Court in its recent Carpenter decision recognized how constant streams of data about us change the ways that privacy should be protected. In holding that enforcement acquisition of cell phone location records requires a warrant, the Court considered the “detailed, encyclopedic, and effortlessly compiled” information available from cell service location records and “the seismic shifts in digital technology” that made these records available, and concluded that people do not necessarily surrender privacy interests to collect data they generate or by engaging in behavior that can be observed publicly. While there was disagreement among Justices as to the sources of privacy norms, two of the dissenters, Justice Alito and Gorsuch, pointed to “expectations of privacy” as vulnerable because they can erode or be defined away.

How this landmark privacy decision affects a wide variety of digital evidence will play out in criminal cases and not in the commercial sector. Nonetheless, the opinions in the case point to a need for a broader set of norms to protect privacy in settings that have been thought to make information public. Privacy can endure, but it needs a more enduring foundation.

Our existing laws also rely heavily on notice and consent—the privacy notices and privacy policies that we encounter online or receive from credit card companies and medical providers, and the boxes we check or forms we sign. These declarations are what provide the basis for the FTC to find deceptive practices and acts when companies fail to do what they said. This system follows the model of informed consent in medical care and human subject research, where consent is often asked for in person, and was imported into internet privacy in the 1990s. The notion of U.S. policy then was to foster growth of the internet by avoiding regulation and promoting a “ market resolution ” in which individuals would be informed about what data is collected and how it would be processed, and could make choices on this basis.

Maybe informed consent was practical two decades ago, but it is a fantasy today. In a constant stream of online interactions, especially on the small screens that now account for the majority of usage, it is unrealistic to read through privacy policies. And people simply don’t.

It is not simply that any particular privacy policies “suck,” as Senator John Kennedy (R-LA) put it in the Facebook hearings. Zeynep Tufecki is right that these disclosures are obscure and complex . Some forms of notice are necessary and attention to user experience can help, but the problem will persist no matter how well designed disclosures are. I can attest that writing a simple privacy policy is challenging, because these documents are legally enforceable and need to explain a variety of data uses; you can be simple and say too little or you can be complete but too complex. These notices have some useful function as a statement of policy against which regulators, journalists, privacy advocates, and even companies themselves can measure performance, but they are functionally useless for most people, and we rely on them to do too much.

At the end of the day, it is simply too much to read through even the plainest English privacy notice, and being familiar with the terms and conditions or privacy settings for all the services we use is out of the question. The recent flood of emails about privacy policies and consent forms we have gotten with the coming of the EU General Data Protection Regulation have offered new controls over what data is collected or information communicated, but how much have they really added to people’s understanding? Wall Street Journal reporter Joanna Stern attempted to analyze all the ones she received (enough paper printed out to stretch more than the length of a football field), but resorted to scanning for a few specific issues. In today’s world of constant connections, solutions that focus on increasing transparency and consumer choice are an incomplete response to current privacy challenges.

Moreover, individual choice becomes utterly meaningless as increasingly automated data collection leaves no opportunity for any real notice, much less individual consent. We don’t get asked for consent to the terms of surveillance cameras on the streets or “beacons” in stores that pick up cell phone identifiers, and house guests aren’t generally asked if they agree to homeowners’ smart speakers picking up their speech. At best, a sign may be posted somewhere announcing that these devices are in place. As devices and sensors increasingly are deployed throughout the environments we pass through, some after-the-fact access and control can play a role, but old-fashioned notice and choice become impossible.

Ultimately, the familiar approaches ask too much of individual consumers. As the President’s Council of Advisers on Science and Technology Policy found in a 2014 report on big data , “the conceptual problem with notice and choice is that it fundamentally places the burden of privacy protection on the individual,” resulting in an unequal bargain, “a kind of market failure.”

This is an impossible burden that creates an enormous disparity of information between the individual and the companies they deal with. As Frank Pasquale ardently dissects in his “Black Box Society,” we know very little about how the businesses that collect our data operate. There is no practical way even a reasonably sophisticated person can get arms around the data that they generate and what that data says about them. After all, making sense of the expanding data universe is what data scientists do. Post-docs and Ph.D.s at MIT (where I am a visiting scholar at the Media Lab) as well as tens of thousands of data researchers like them in academia and business are constantly discovering new information that can be learned from data about people and new ways that businesses can—or do—use that information. How can the rest of us who are far from being data scientists hope to keep up?

As a result, the businesses that use the data know far more than we do about what our data consists of and what their algorithms say about us. Add this vast gulf in knowledge and power to the absence of any real give-and-take in our constant exchanges of information, and you have businesses able by and large to set the terms on which they collect and share this data.

Businesses are able by and large to set the terms on which they collect and share this data. This is not a “market resolution” that works.

This is not a “market resolution” that works. The Pew Research Center has tracked online trust and attitudes toward the internet and companies online. When Pew probed with surveys and focus groups in 2016, it found that “while many Americans are willing to share personal information in exchange for tangible benefits, they are often cautious about disclosing their information and frequently unhappy about that happens to that information once companies have collected it.” Many people are “uncertain, resigned, and annoyed.” There is a growing body of survey research in the same vein. Uncertainty, resignation, and annoyance hardly make a recipe for a healthy and sustainable marketplace, for trusted brands, or for consent of the governed.

Consider the example of the journalist Julia Angwin. She spent a year trying to live without leaving digital traces, which she described in her book “Dragnet Nation.” Among other things, she avoided paying by credit card and established a fake identity to get a card for when she couldn’t avoid using one; searched hard to find encrypted cloud services for most email; adopted burner phones that she turned off when not in use and used very little; and opted for paid subscription services in place of ad-supported ones. More than a practical guide to protecting one’s data privacy, her year of living anonymously was an extended piece of performance art demonstrating how much digital surveillance reveals about our lives and how hard it is to avoid. The average person should not have to go to such obsessive lengths to ensure that their identities or other information they want to keep private stays private. We need a fair game.

Shaping laws capable of keeping up

As policymakers consider how the rules might change, the Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights we developed in the Obama administration has taken on new life as a model. The Los Angeles Times , The Economist , and The New York Times all pointed to this bill of rights in urging Congress to act on comprehensive privacy legislation, and the latter said “there is no need to start from scratch …” Our 2012 proposal needs adapting to changes in technology and politics, but it provides a starting point for today’s policy discussion because of the wide input it got and the widely accepted principles it drew on.

The bill of rights articulated seven basic principles that should be legally enforceable by the Federal Trade Commission: individual control, transparency, respect for the context in which the data was obtained, access and accuracy, focused collection, security, and accountability. These broad principles are rooted in longstanding and globally-accepted “fair information practices principles.” To reflect today’s world of billions of devices interconnected through networks everywhere, though, they are intended to move away from static privacy notices and consent forms to a more dynamic framework, less focused on collection and process and more on how people are protected in the ways their data is handled. Not a checklist, but a toolbox. This principles-based approach was meant to be interpreted and fleshed out through codes of conduct and case-by-case FTC enforcement—iterative evolution, much the way both common law and information technology developed.

As policymakers consider how the rules might change, the Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights developed in the Obama administration has taken on new life as a model. The bill of rights articulated seven basic principles that should be legally enforceable by the Federal Trade Commission.

The other comprehensive model that is getting attention is the EU’s newly effective General Data Protection Regulation. For those in the privacy world, this has been the dominant issue ever since it was approved two years ago, but even so, it was striking to hear “the GDPR” tossed around as a running topic of congressional questions for Mark Zuckerberg. The imminence of this law, its application to Facebook and many other American multinational companies, and its contrast with U.S. law made GDPR a hot topic. It has many people wondering why the U.S. does not have a similar law, and some saying the U.S. should follow the EU model.

I dealt with the EU law since it was in draft form while I led U.S. government engagement with the EU on privacy issues alongside developing our own proposal. Its interaction with U.S. law and commerce has been part of my life as an official, a writer and speaker on privacy issues, and a lawyer ever since. There’s a lot of good in it, but it is not the right model for America.

There’s a lot of good in the GDPR, but it is not the right model for America.

What is good about the EU law? First of all, it is a law—one set of rules that applies to all personal data across the EU. Its focus on individual data rights in theory puts human beings at the center of privacy practices, and the process of complying with its detailed requirements has forced companies to take a close look at what data they are collecting, what they use it for, and how they keep it and share it—which has proved to be no small task. Although the EU regulation is rigid in numerous respects, it can be more subtle than is apparent at first glance. Most notably, its requirement that consent be explicit and freely given is often presented in summary reports as prohibiting collecting any personal data without consent; in fact, the regulation allows other grounds for collecting data and one effect of the strict definition of consent is to put more emphasis on these other grounds. How some of these subtleties play out will depend on how 40 different regulators across the EU apply the law, though. European advocacy groups were already pursuing claims against “ les GAFAM ” (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft) as the regulation went into effect.

The EU law has its origins in the same fair information practice principles as the Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights. But the EU law takes a much more prescriptive and process-oriented approach, spelling out how companies must manage privacy and keep records and including a “right to be forgotten” and other requirements hard to square with our First Amendment. Perhaps more significantly, it may not prove adaptable to artificial intelligence and new technologies like autonomous vehicles that need to aggregate masses of data for machine learning and smart infrastructure. Strict limits on the purposes of data use and retention may inhibit analytical leaps and beneficial new uses of information. A rule requiring human explanation of significant algorithmic decisions will shed light on algorithms and help prevent unfair discrimination but also may curb development of artificial intelligence. These provisions reflect a distrust of technology that is not universal in Europe but is a strong undercurrent of its political culture.

We need an American answer—a more common law approach adaptable to changes in technology—to enable data-driven knowledge and innovation while laying out guardrails to protect privacy. The Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights offers a blueprint for such an approach.

Sure, it needs work, but that’s what the give-and-take of legislating is about. Its language on transparency came out sounding too much like notice-and-consent, for example. Its proposal for fleshing out the application of the bill of rights had a mixed record of consensus results in trial efforts led by the Commerce Department.

It also got some important things right. In particular, the “respect for context” principle is an important conceptual leap. It says that a people “have a right to expect that companies will collect, use, and disclose personal data in ways that are consistent with the context in which consumers provide the data.” This breaks from the formalities of privacy notices, consent boxes, and structured data and focuses instead on respect for the individual. Its emphasis on the interactions between an individual and a company and circumstances of the data collection and use derives from the insight of information technology thinker Helen Nissenbaum . To assess privacy interests, “it is crucial to know the context—who is gathering the information, who is analyzing it, who is disseminating and to whom, the nature of the information, the relationships among the various parties, and even larger institutional and social circumstances.”

We need an American answer—a more common law approach adaptable to changes in technology—to enable data-driven knowledge and innovation while laying out guardrails to protect privacy.

Context is complicated—our draft legislation listed 11 different non-exclusive factors to assess context. But that is in practice the way we share information and form expectations about how that information will be handled and about our trust in the handler. We bare our souls and our bodies to complete strangers to get medical care, with the understanding that this information will be handled with great care and shared with strangers only to the extent needed to provide care. We share location information with ride-sharing and navigation apps with the understanding that it enables them to function, but Waze ran into resistance when that functionality required a location setting of “always on.” Danny Weitzner, co-architect of the Privacy Bill of Rights, recently discussed how the respect for context principle “would have prohibited [Cambridge Analytica] from unilaterally repurposing research data for political purposes” because it establishes a right “not to be surprised by how one’s personal data issued.” The Supreme Court’s Carpenter decision opens up expectations of privacy in information held by third parties to variations based on the context.

The Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights does not provide any detailed prescription as to how the context principle and other principles should apply in particular circumstances. Instead, the proposal left such application to case-by-case adjudication by the FTC and development of best practices, standards, and codes of conduct by organizations outside of government, with incentives to vet these with the FTC or to use internal review boards similar to those used for human subject research in academic and medical settings. This approach was based on the belief that the pace of technological change and the enormous variety of circumstances involved need more adaptive decisionmaking than current approaches to legislation and government regulations allow. It may be that baseline legislation will need more robust mandates for standards than the Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights contemplated, but any such mandates should be consistent with the deeply embedded preference for voluntary, collaboratively developed, and consensus-based standards that has been a hallmark of U.S. standards development.

In hindsight, the proposal could use a lodestar to guide the application of its principles—a simple golden rule for privacy: that companies should put the interests of the people whom data is about ahead of their own. In some measure, such a general rule would bring privacy protection back to first principles: some of the sources of law that Louis Brandeis and Samuel Warren referred to in their famous law review article were cases in which the receipt of confidential information or trade secrets led to judicial imposition of a trust or duty of confidentiality. Acting as a trustee carries the obligation to act in the interests of the beneficiaries and to avoid self-dealing.

A Golden Rule of Privacy that incorporates a similar obligation for one entrusted with personal information draws on several similar strands of the privacy debate. Privacy policies often express companies’ intention to be “good stewards of data;” the good steward also is supposed to act in the interests of the principal and avoid self-dealing. A more contemporary law review parallel is Yale law professor Jack Balkin’s concept of “ information fiduciaries ,” which got some attention during the Zuckerberg hearing when Senator Brian Schatz (D-HI) asked Zuckerberg to comment on it. The Golden Rule of Privacy would import the essential duty without importing fiduciary law wholesale. It also resonates with principles of “respect for the individual,” “beneficence,” and “justice” in ethical standards for human subject research that influence emerging ethical frameworks for privacy and data use. Another thread came in Justice Gorsuch’s Carpenter dissent defending property law as a basis for privacy interests: he suggested that entrusting someone with digital information may be a modern equivalent of a “bailment” under classic property law, which imposes duties on the bailee. And it bears some resemblance to the GDPR concept of “ legitimate interest ,” which permits the processing of personal data based on a legitimate interest of the processor, provided that this interest is not outweighed by the rights and interests of the subject of the data.

The fundamental need for baseline privacy legislation in America is to ensure that individuals can trust that data about them will be used, stored, and shared in ways that are consistent with their interests and the circumstances in which it was collected. This should hold regardless of how the data is collected, who receives it, or the uses it is put to. If it is personal data, it should have enduring protection.

The fundamental need for baseline privacy legislation in America is to ensure that individuals can trust that data about them will be used, stored, and shared in ways that are consistent with their interests and the circumstances in which it was collected.

Such trust is an essential building block of a sustainable digital world. It is what enables the sharing of data for socially or economically beneficial uses without putting human beings at risk. By now, it should be clear that trust is betrayed too often, whether by intentional actors like Cambridge Analytica or Russian “ Fancy Bears ,” or by bros in cubes inculcated with an imperative to “ deploy or die .”

Trust needs a stronger foundation that provides people with consistent assurance that data about them will be handled fairly and consistently with their interests. Baseline principles would provide a guide to all businesses and guard against overreach, outliers, and outlaws. They would also tell the world that American companies are bound by a widely-accepted set of privacy principles and build a foundation for privacy and security practices that evolve with technology.

Resigned but discontented consumers are saying to each other, “I think we’re playing a losing game.” If the rules don’t change, they may quit playing.

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars.

Artificial Intelligence Internet & Telecommunications Privacy

Courts & Law

Governance Studies

Center for Technology Innovation

Artificial Intelligence and Emerging Technology Initiative The Privacy Debate

Nicol Turner Lee, Renée Cummings, Lisa Rice

April 8, 2024

Ryan Hass, Colin Kahl

April 5, 2024

April 4, 2024

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics