An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Adv Pharm Technol Res

- v.2(2); Apr-Jun 2011

Intellectual property rights: An overview and implications in pharmaceutical industry

Chandra nath saha.

Quality Assurance Department, Claris Lifesciences Ltd., Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India

Sanjib Bhattacharya

1 Pharmacognosy Division, Bengal School of Technology (A College of Pharmacy), Sugandha, Hooghly, West Bengal, India

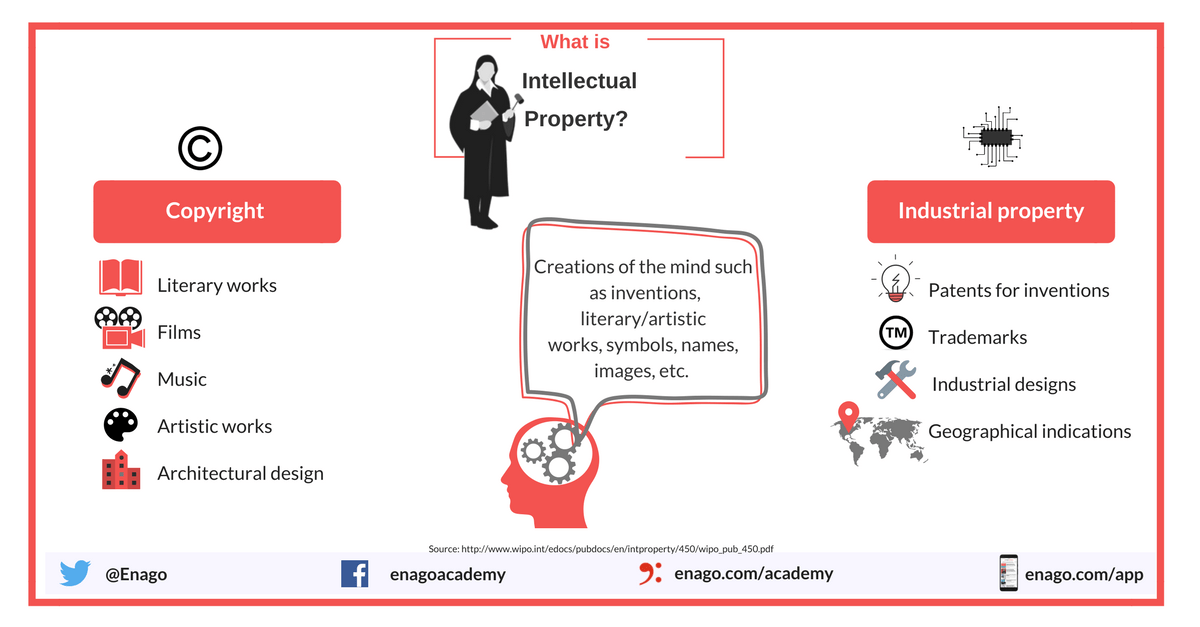

Intellectual property rights (IPR) have been defined as ideas, inventions, and creative expressions based on which there is a public willingness to bestow the status of property. IPR provide certain exclusive rights to the inventors or creators of that property, in order to enable them to reap commercial benefits from their creative efforts or reputation. There are several types of intellectual property protection like patent, copyright, trademark, etc. Patent is a recognition for an invention, which satisfies the criteria of global novelty, non-obviousness, and industrial application. IPR is prerequisite for better identification, planning, commercialization, rendering, and thereby protection of invention or creativity. Each industry should evolve its own IPR policies, management style, strategies, and so on depending on its area of specialty. Pharmaceutical industry currently has an evolving IPR strategy requiring a better focus and approach in the coming era.

INTRODUCTION

Intellectual property (IP) pertains to any original creation of the human intellect such as artistic, literary, technical, or scientific creation. Intellectual property rights (IPR) refers to the legal rights given to the inventor or creator to protect his invention or creation for a certain period of time.[ 1 ] These legal rights confer an exclusive right to the inventor/creator or his assignee to fully utilize his invention/creation for a given period of time. It is very well settled that IP play a vital role in the modern economy. It has also been conclusively established that the intellectual labor associated with the innovation should be given due importance so that public good emanates from it. There has been a quantum jump in research and development (R&D) costs with an associated jump in investments required for putting a new technology in the market place.[ 2 ] The stakes of the developers of technology have become very high, and hence, the need to protect the knowledge from unlawful use has become expedient, at least for a period, that would ensure recovery of the R&D and other associated costs and adequate profits for continuous investments in R&D.[ 3 ] IPR is a strong tool, to protect investments, time, money, effort invested by the inventor/creator of an IP, since it grants the inventor/creator an exclusive right for a certain period of time for use of his invention/creation. Thus IPR, in this way aids the economic development of a country by promoting healthy competition and encouraging industrial development and economic growth. Present review furnishes a brief overview of IPR with special emphasis on pharmaceuticals.

BRIEF HISTORY

The laws and administrative procedures relating to IPR have their roots in Europe. The trend of granting patents started in the fourteenth century. In comparison to other European countries, in some matters England was technologically advanced and used to attract artisans from elsewhere, on special terms. The first known copyrights appeared in Italy. Venice can be considered the cradle of IP system as most legal thinking in this area was done here; laws and systems were made here for the first time in the world, and other countries followed in due course.[ 4 ] Patent act in India is more than 150 years old. The inaugural one is the 1856 Act, which is based on the British patent system and it has provided the patent term of 14 years followed by numerous acts and amendments.[ 1 ]

Types of Intellectual Properties and their Description

Originally, only patent, trademarks, and industrial designs were protected as ‘Industrial Property’, but now the term ‘Intellectual Property’ has a much wider meaning. IPR enhances technology advancement in the following ways:[ 1 – 4 ]

- (a) it provides a mechanism of handling infringement, piracy, and unauthorized use

- (b) it provides a pool of information to the general public since all forms of IP are published except in case of trade secrets.

IP protection can be sought for a variety of intellectual efforts including

- (i) Patents

- (ii) Industrial designs relates to features of any shape, configuration, surface pattern, composition of lines and colors applied to an article whether 2-D, e.g., textile, or 3-D, e.g., toothbrush[ 5 ]

- (iii) Trademarks relate to any mark, name, or logo under which trade is conducted for any product or service and by which the manufacturer or the service provider is identified. Trademarks can be bought, sold, and licensed. Trademark has no existence apart from the goodwill of the product or service it symbolizes[ 6 ]

- (iv) Copyright relates to expression of ideas in material form and includes literary, musical, dramatic, artistic, cinematography work, audio tapes, and computer software[ 7 ]

- (v) Geographical indications are indications, which identify as good as originating in the territory of a country or a region or locality in that territory where a given quality, reputation, or other characteristic of the goods is essentially attributable to its geographical origin[ 8 ]

A patent is awarded for an invention, which satisfies the criteria of global novelty, non-obviousness, and industrial or commercial application. Patents can be granted for products and processes. As per the Indian Patent Act 1970, the term of a patent was 14 years from the date of filing except for processes for preparing drugs and food items for which the term was 7 years from the date of the filing or 5 years from the date of the patent, whichever is earlier. No product patents were granted for drugs and food items.[ 9 ] A copyright generated in a member country of the Berne Convention is automatically protected in all the member countries, without any need for registration. India is a signatory to the Berne Convention and has a very good copyright legislation comparable to that of any country. However, the copyright will not be automatically available in countries that are not the members of the Berne Convention. Therefore, copyright may not be considered a territorial right in the strict sense. Like any other property IPR can be transferred, sold, or gifted.[ 7 ]

Role of Undisclosed Information in Intellectual Property

Protection of undisclosed information is least known to players of IPR and also least talked about, although it is perhaps the most important form of protection for industries, R&D institutions and other agencies dealing with IPR. Undisclosed information, generally known as trade secret or confidential information, includes formula, pattern, compilation, programme, device, method, technique, or process. Protection of undisclosed information or trade secret is not really new to humanity; at every stage of development people have evolved methods to keep important information secret, commonly by restricting the knowledge to their family members. Laws relating to all forms of IPR are at different stages of implementation in India, but there is no separate and exclusive law for protecting undisclosed information/trade secret or confidential information.[ 10 ]

Pressures of globalisation or internationalisation were not intense during 1950s to 1980s, and many countries, including India, were able to manage without practising a strong system of IPR. Globalization driven by chemical, pharmaceutical, electronic, and IT industries has resulted into large investment in R&D. This process is characterized by shortening of product cycle, time and high risk of reverse engineering by competitors. Industries came to realize that trade secrets were not adequate to guard a technology. It was difficult to reap the benefits of innovations unless uniform laws and rules of patents, trademarks, copyright, etc. existed. That is how IPR became an important constituent of the World Trade Organization (WTO).[ 11 ]

Rationale of Patent

Patent is recognition to the form of IP manifested in invention. Patents are granted for patentable inventions, which satisfy the requirements of novelty and utility under the stringent examination and opposition procedures prescribed in the Indian Patents Act, 1970, but there is not even a prima-facie presumption as to the validity of the patent granted.[ 9 ]

Most countries have established national regimes to provide protection to the IPR within its jurisdiction. Except in the case of copyrights, the protection granted to the inventor/creator in a country (such as India) or a region (such as European Union) is restricted to that territory where protection is sought and is not valid in other countries or regions.[ 1 ] For example, a patent granted in India is valid only for India and not in the USA. The basic reason for patenting an invention is to make money through exclusivity, i.e., the inventor or his assignee would have a monopoly if,

- (a) the inventor has made an important invention after taking into account the modifications that the customer, and

- (b) if the patent agent has described and claimed the invention correctly in the patent specification drafted, then the resultant patent would give the patent owner an exclusive market.

The patentee can exercise his exclusivity either by marketing the patented invention himself or by licensing it to a third party.

The following would not qualify as patents:

- (i) An invention, which is frivolous or which claims anything obvious or contrary to the well established natural law. An invention, the primary or intended use of which would be contrary to law or morality or injurious to public health

- (ii) A discovery, scientific theory, or mathematical method

- (iii) A mere discovery of any new property or new use for a known substance or of the mere use of a known process, machine, or apparatus unless such known process results in a new product or employs at least one new reactant

- (iv) A substance obtained by a mere admixture resulting only in the aggregation of the properties of the components thereof or a process for producing such substance

- (v) A mere arrangement or re-arrangement or duplication of a known device each functioning independently of one another in its own way

- (vi) A method of agriculture or horticulture

- (vii) Any process for the medicinal, surgical, curative, prophylactic diagnostic, therapeutic or other treatment of human beings or any process for a similar treatment of animals to render them free of disease or to increase their economic value or that of their products

- (viii) An invention relating to atomic energy

- (ix) An invention, which is in effect, is traditional knowledge

Rationale of License

A license is a contract by which the licensor authorizes the licensee to perform certain activities, which would otherwise have been unlawful. For example, in a patent license, the patentee (licensor) authorizes the licensee to exercise defined rights over the patent. The effect is to give to the licensee a right to do what he/she would otherwise be prohibited from doing, i.e., a license makes lawful what otherwise would be unlawful.[ 12 ]

The licensor may also license ‘know-how’ pertaining to the execution of the licensed patent right such as information, process, or device occurring or utilized in a business activity can also be included along with the patent right in a license agreement. Some examples of know-how are:

- (i) technical information such as formulae, techniques, and operating procedures and

- (ii) commercial information such as customer lists and sales data, marketing, professional and management procedures.

Indeed, any technical, trade, commercial, or other information, may be capable of being the subject of protection.[ 13 ]

Benefits to the licensor:

- (i) Opens new markets

- (ii) Creates new areas for revenue generation

- (iii) Helps overcome the challenge of establishing the technology in different markets especially in foreign countries – lower costs and risk and savings on distribution and marketing expenses

Benefits to the licensee are:

- (i) Savings on R&D and elimination of risks associated with R&D

- (ii) Quick exploitation of market requirements before the market interest wanes

- (iii) Ensures that products are the latest

The Role of Patent Cooperation Treaty

The patent cooperation treaty (PCT) is a multilateral treaty entered into force in 1978. Through PCT, an inventor of a member country contracting state of PCT can simultaneously obtain priority for his/her invention in all or any of the member countries, without having to file a separate application in the countries of interest, by designating them in the PCT application. All activities related to PCT are coordinated by the world intellectual property organization (WIPO) situated in Geneva.[ 14 ]

In order to protect invention in other countries, it is required to file an independent patent application in each country of interest; in some cases, within a stipulated time to obtain priority in these countries. This would entail a large investment, within a short time, to meet costs towards filing fees, translation, attorney charges, etc. In addition, it is assumed that due to the short time available for making the decision on whether to file a patent application in a country or not, may not be well founded.[ 15 ]

Inventors of contracting states of PCT on the other hand can simultaneously obtain priority for their inventions without having to file separate application in the countries of interest; thus, saving the initial investments towards filing fees, translation, etc. In addition, the system provides much longer time for filing patent application in the member countries.[ 15 , 16 ]

The time available under Paris convention for securing priority in other countries is 12 months from the date of initial filing. Under the PCT, the time available could be as much as minimum 20 and maximum 31 months. Further, an inventor is also benefited by the search report prepared under the PCT system to be sure that the claimed invention is novel. The inventor could also opt for preliminary examination before filing in other countries to be doubly sure about the patentability of the invention.[ 16 ]

Management of Intellectual Property in Pharmaceutical Industries

More than any other technological area, drugs and pharmaceuticals match the description of globalization and need to have a strong IP system most closely. Knowing that the cost of introducing a new drug into the market may cost a company anywhere between $ 300 million to $1000 million along with all the associated risks at the developmental stage, no company will like to risk its IP becoming a public property without adequate returns. Creating, obtaining, protecting, and managing IP must become a corporate activity in the same manner as the raising of resources and funds. The knowledge revolution, which we are sure to witness, will demand a special pedestal for IP and treatment in the overall decision-making process.[ 17 ]

Competition in the global pharmaceutical industry is driven by scientific knowledge rather than manufacturing know-how and a company's success will be largely dependent on its R&D efforts. Therefore, investments in R&D in the drug industry are very high as a percentage of total sales; reports suggest that it could be as much as 15% of the sale. One of the key issues in this industry is the management of innovative risks while one strives to gain a competitive advantage over rival organizations. There is high cost attached to the risk of failure in pharmaceutical R&D with the development of potential medicines that are unable to meet the stringent safety standards, being terminated, sometimes after many years of investment. For those medicines that do clear development hurdles, it takes about 8-10 years from the date when the compound was first synthesized. As product patents emerge as the main tools for protecting IP, the drug companies will have to shift their focus of R&D from development of new processes for producing known drugs towards development of a new drug molecule and new chemical entity (NCE). During the 1980s, after a period of successfully treating many diseases of short-term duration, the R&D focus shifted to long duration (chronic) diseases. While looking for the global market, one has to ensure that requirements different regulatory authorities must be satisfied.[ 18 ]

It is understood that the documents to be submitted to regulatory authorities have almost tripled in the last ten years. In addition, regulatory authorities now take much longer to approve a new drug. Consequently, the period of patent protection is reduced, resulting in the need of putting in extra efforts to earn enough profits. The situation may be more severe in the case of drugs developed through the biotechnology route especially those involving utilization of genes. It is likely that the industrialized world would soon start canvassing for longer protection for drugs. It is also possible that many governments would exercise more and more price control to meet public goals. This would on one hand emphasize the need for reduced cost of drug development, production, and marketing, and on the other hand, necessitate planning for lower profit margins so as to recover costs over a longer period. It is thus obvious that the drug industry has to wade through many conflicting requirements. Many different strategies have been evolved during the last 10 to 15 years for cost containment and trade advantage. Some of these are out sourcing of R&D activity, forming R&D partnerships and establishing strategic alliances.[ 19 ]

Nature of Pharmaceutical Industry

The race to unlock the secrets of human genome has produced an explosion of scientific knowledge and spurred the development of new technologies that are altering the economics of drug development. Biopharmaceuticals are likely to enjoy a special place and the ultimate goal will be to have personalized medicines, as everyone will have their own genome mapped and stored in a chip. Doctors will look at the information in the chip(s) and prescribe accordingly. The important IP issue associated would be the protection of such databases of personal information. Biotechnologically developed drugs will find more and more entry into the market. The protection procedure for such drug will be a little different from those conventional drugs, which are not biotechnologically developed. Microbial strains used for developing a drug or vaccine needs to be specified in the patent document. If the strain is already known and reported in the literature usually consulted by scientists, then the situation is simple. However, many new strains are discovered and developed continuously and these are deposited with International depository authorities under the Budapest Treaty. While doing a novelty search, the databases of these depositories should also be consulted. Companies do not usually go for publishing their work, but it is good to make it a practice not to disclose the invention through publications or seminars until a patent application has been filed.[ 20 ]

While dealing with microbiological inventions, it is essential to deposit the strain in one of the recognized depositories who would give a registration number to the strain which should be quoted in the patent specification. This obviates the need of describing a life form on paper. Depositing a strain also costs money, but this is not much if one is not dealing with, for example cell lines. Further, for inventions involving genes, gene expression, DNA, and RNA, the sequences also have to be described in the patent specification as has been seen in the past. The alliances could be for many different objectives such as for sharing R&D expertise and facilities, utilizing marketing networks and sharing production facilities. While entering into an R&D alliance, it is always advisable to enter into a formal agreement covering issues like ownership of IP in different countries, sharing of costs of obtaining and maintaining IP and revenue accruing from it, methods of keeping trade secrets, accounting for IP of each company before the alliance and IP created during the project but not addressed in the plan, dispute settlements. It must be remembered that an alliance would be favorable if the IP portfolio is stronger than that of concerned partner. There could be many other elements of this agreement. Many drug companies will soon use the services of academic institutions, private R&D agencies, R&D institutions under government in India and abroad by way of contract research. All the above aspects mentioned above will be useful. Special attention will have to be paid towards maintaining confidentiality of research.[ 1 – 18 ]

The current state of the pharmaceutical industry indicates that IPR are being unjustifiably strengthened and abused at the expense of competition and consumer welfare. The lack of risk and innovation on the part of the drug industry underscores the inequity that is occurring at the expense of public good. It is an unfairness that cannot be cured by legislative reform alone. While congressional efforts to close loopholes in current statutes, along with new legislation to curtail additionally unfavorable business practices of the pharmaceutical industry, may provide some mitigation, antitrust law must appropriately step in.[ 21 ] While antitrust laws have appropriately scrutinized certain business practices employed by the pharmaceutical industry, such as mergers and acquisitions and agreements not to compete, there are several other practices that need to be addressed. The grant of patents on minor elements of an old drug, reformulations of old drugs to secure new patents, and the use of advertising and brand name development to increase the barriers for generic market entrants are all areas in which antitrust law can help stabilize the balance between rewarding innovation and preserving competition.[ 20 ]

Traditional medicine dealing with natural botanical products is an important part of human health care in many developing countries and also in developed countries, increasing their commercial value. The world market for such medicines has reached US $ 60 billion, with annual growth rates of between 5% and 15%. Although purely traditional knowledge based medicines do not qualify for patent, people often claim so. Researchers or companies may also claim IPR over biological resources and/or traditional knowledge, after slightly modifying them. The fast growth of patent applications related to herbal medicine shows this trend clearly. The patent applications in the field of natural products, traditional herbal medicine and herbal medicinal products are dealt with own IPR policies of each country as food, pharmaceutical and cosmetics purview, whichever appropriate. Medicinal plants and related plant products are important targets of patent claims since they have become of great interest to the global organized herbal drug and cosmetic industries.[ 22 ]

Some Special Aspects of Drug Patent Specification

Writing patent specification is a highly professional skill, which is acquired over a period of time and needs a good combination of scientific, technological, and legal knowledge. Claims in any patent specification constitute the soul of the patent over which legal proprietary is sought. Discovery of a new property in a known material is not patentable. If one can put the property to a practical use one has made an invention which may be patentable. A discovery that a known substance is able to withstand mechanical shock would not be patentable but a railway sleeper made from the material could well be patented. A substance may not be new but has been found to have a new property. It may be possible to patent it in combination with some other known substances if in combination they exhibit some new result. The reason is that no one has earlier used that combination for producing an insecticide or fertilizer or drug. It is quite possible that an inventor has created a new molecule but its precise structure is not known. In such a case, description of the substance along with its properties and the method of producing the same will play an important role.[ 23 ]

Combination of known substances into useful products may be a subject matter of a patent if the substances have some working relationship when combined together. In this case, no chemical reaction takes place. It confers only a limited protection. Any use by others of individual parts of the combination is beyond the scope of the patent. For example, a patent on aqua regia will not prohibit any one from mixing the two acids in different proportions and obtaining new patents. Methods of treatment for humans and animals are not patentable in most of the countries (one exception is USA) as they are not considered capable of industrial application. In case of new pharmaceutical use of a known substance, one should be careful in writing claims as the claim should not give an impression of a method of treatment. Most of the applications relate to drugs and pharmaceuticals including herbal drugs. A limited number of applications relate to engineering, electronics, and chemicals. About 62% of the applications are related to drugs and pharmaceuticals.[ 1 – 24 ]

CONCLUSIONS

It is obvious that management of IP and IPR is a multidimensional task and calls for many different actions and strategies which need to be aligned with national laws and international treaties and practices. It is no longer driven purely by a national perspective. IP and its associated rights are seriously influenced by the market needs, market response, cost involved in translating IP into commercial venture and so on. In other words, trade and commerce considerations are important in the management of IPR. Different forms of IPR demand different treatment, handling, planning, and strategies and engagement of persons with different domain knowledge such as science, engineering, medicines, law, finance, marketing, and economics. Each industry should evolve its own IP policies, management style, strategies, etc. depending on its area of specialty. Pharmaceutical industry currently has an evolving IP strategy. Since there exists the increased possibility that some IPR are invalid, antitrust law, therefore, needs to step in to ensure that invalid rights are not being unlawfully asserted to establish and maintain illegitimate, albeit limited, monopolies within the pharmaceutical industry. Still many things remain to be resolved in this context.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

IntellectualProperty →

No results found in working knowledge.

- Were any results found in one of the other content buckets on the left?

- Try removing some search filters.

- Use different search filters.

AI and IP: Theory to Policy and Back Again – Policy and Research Recommendations at the Intersection of Artificial Intelligence and Intellectual Property

- Open access

- Published: 20 June 2023

- Volume 54 , pages 916–940, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Peter Georg Picht 1 &

- Florent Thouvenin 2

8869 Accesses

4 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The interaction between artificial intelligence and intellectual property rights (IPRs) is one of the key areas of development in intellectual property law. After much, albeit selective, debate, it seems to be gaining increasing practical relevance through intense AI-related market activity, an initial set of case law on the matter, and policy initiatives by international organizations and lawmakers. Against this background, Zurich University’s Center for Intellectual Property and Competition Law is conducting, together with the Swiss Intellectual Property Institute, a research and policy project that explores the future of intellectual property law in an AI context. This paper briefly describes the AI/IP Research Project and presents an initial set of policy recommendations for the development of IP law with a view to AI. The recommendations address topics such as AI inventorship in patent law; AI authorship in copyright law; the need for sui generis rights to protect innovative AI output; rules for the allocation of AI-related IPRs; IP protection carve-outs in order to facilitate AI system development, training, and testing; the use of AI tools by IP offices; and suitable software protection and data usage regimes.

Similar content being viewed by others

International Perspectives on Regulatory Frameworks: AI Through the Lens of Patent Law

The Challenge of Recognizing Artificial Intelligence as Legal Inventor: Implications and Analysis of Patent Laws

Can the Singularity Be Patented? (And Other IP Conundrums for Converging Technologies)

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The interaction between artificial intelligence (AI) and intellectual property rights (IPRs) is one of the key areas of development in intellectual property law. After much, albeit selective, debate, it seems to be gaining increasing practical relevance through intense AI-related market activity, an initial set of case law on the matter, and policy initiatives by international organizations (e.g. WIPO, EPO) and lawmakers.

Against this background, Zurich University’s Center for Intellectual Property and Competition Law (CIPCO) is conducting, together with the Swiss Intellectual Property Institute (IPI), Footnote 1 a research and policy project (hereinafter the “AI/IP Research Project” or “Project”) that explores the future of intellectual property law in an AI context. This paper briefly describes the AI/IP Research Project (Sect. 2 ) and presents (Sect. 3 ) an initial set of policy and research recommendations (“Recommendations”) for the development of IP law with a view to AI. It concludes (Sect. 4 ) with a look at possible topics for additional recommendations. For a terminological and technical description of artificial intelligence, Footnote 2 and for further background to the Recommendations below, as well as for AI/IP aspects that they do not address, this paper refers to the rich existing literature. Footnote 3

2 The AI/IP Research Project

Initiated in 2021, the AI/IP Research Project aims at (i) gaining an overview of the current state of affairs in AI/IP, (ii) assessing issues crucial at the present stage, and (iii) deriving policy recommendations for how European jurisdictions, including Switzerland, should position themselves in international collaboration and in national law-making regarding AI/IP. Methodologically, the Project chooses a multi-component approach that has included, so far, mainly a comparative analysis of the AI/IP law situation – across the range of major IP rights Footnote 4 – in various jurisdictions, the gathering of first-hand empirical evidence through stakeholder input (e.g. industry representatives, specialized counsel, members of state and supra-state IP administrations), and an interdisciplinary exchange with innovation economists and computer scientists specializing in AI. As a backbone of its 2021/2022 activities, besides desk research work, the Project conducted a series of workshops Footnote 5 in which legal, economic and technical experts, as well as company representatives and other stakeholders, presented and discussed key AI/IP aspects. Footnote 6 Our warmest thanks go to all those who have participated and are participating in the Project. Footnote 7 Their support is invaluable in the attempt to further an appropriate IP law framework for AI. At its next stage, the Project will, inter alia , intensify the intra-disciplinary legal discourse with scholars working on AI from angles other than core IP law, e.g. data law, contract law, and liability law.

3 Policy Recommendations

We distinguish three types of Policy Recommendations: Implementation Recommendations intend to guide the next steps in law and policy-making. We think, based on previous discourse and experience, that their beneficial effects are likely enough to put them into practice. Consideration Recommendations describe courses which the law should probably take. Some further reflection and research seem, however, advisable before implementing them. Research Recommendations identify issues that research should address, to produce consideration recommendations on these matters as well.

3.1 Implementation Recommendations

3.1.1 inventorship in patent law, 3.1.1.1 recommendation.

The law should be amended to allow the designation of AI systems as inventors. Meanwhile, patent applications should be free to designate persons as “proxy inventors” while also describing the inventive activity of the AI system. There should be more disclosure on such inventive activity. AI systems’ innovative abilities must become part of the PHOSITA concept and related protectability thresholds.

Where an AI system generated inventive output without inventive human intervention, the patent application should be permitted to say so and name the AI system as the inventor, along with a natural person or legal entity who claims ownership of the patent application and a resulting patent.

Until legal rules have (where necessary) been changed to accommodate the above Recommendation, natural persons should – as a temporary workaround – be allowed to act and register as “proxy inventors”, as long as they disclose this role and the AI system for which they act as proxy. Such disclosure should be provided in the description.

More honest recognition of the increasingly innovative role AI systems play in invention processes, however, also calls for stricter requirements for patent applications to disclose details regarding the nature, extent, and mechanism of an AI system’s inventive contribution.

Furthermore, AI system abilities must become part of the PHOSITA Footnote 8 concept and related protectability thresholds. A potential raising of the protectability bar resulting therefrom is welcome as it mitigates the risk of AI patent thickets.

3.1.1.2 Background

The question of whether patent law can and should recognize AI systems as inventors, if they generate otherwise patentable technical solutions without an inventive contribution by humans, is arguably the most conspicuous issue in the current AI/IP landscape. Besides academic debate, Footnote 9 the multi-pronged DABUS litigation plays a key role as it probes into a range of the most important patent jurisdictions on whether their existing rules permit AI system inventorship. So far, the track record of patent applications based on the inventions (allegedly) made by DABUS is not a very successful one and the rejecting patent offices or courts seem right in finding that the currently applicable patent law rules are oriented to human, not AI inventorship. Footnote 10

De lege ferenda , however, at a forward-looking policy level, important reasons weigh in favour of patent applications that openly describe the role AI systems have played in the invention process. A need to definitively assess whether the human contribution to an invention, relative to the contribution made by an AI system, is sufficient to establish human inventorship, and thus patentability, unnecessarily harms legal certainty and uses patent office resources. It is one of the functions of the patent system to instruct the public about the progress of innovation and, thereby, to induce further innovation, for instance in the form of follow-on inventions. Necessitating patent applicants to disguise the true relation between human and AI contributions to an invention, because they must otherwise fear that their application will be rejected, hampers this function. Such impairment becomes even stronger where AI-generated inventions are not submitted for patenting at all but remain confined to the realm of trade secrets. In fact, industry participants in the Project state that companies do prefer trade secrets over patents for AI-generated inventions where they perceive a high risk of ending up – after having to disclose their invention in a patent application – without IP protection because the determinant role of their inventive AI systems, if admitted, prevents patentability.

Remarkably, these and further advantages of openness regarding inventive AI systems have made courts creative in searching for solutions even de lege lata , under the provisions of current patent law. The German Federal Patent Court (“ Bundespatentgericht ”) and the EPO Boards of Appeal now seem to accept a sort of proxy human inventorship. According to this concept, an application must still formally name a natural person as the inventor, but it can, at the same time, explain that the inventive acts were performed by an AI system. Footnote 11 Although unnecessarily complicated and formalistic, the proxy human inventor approach presents an acceptable transitional solution until patent laws can be changed as recommended here.

Even if this patent law reform occurs, it will not obviate the need to designate the natural – or possibly legal ( cf . Sect. 3.2.1 ) – person who becomes the initial owner of the granted patent and who, consequently, acquires the rights and obligations related to this position. Our Recommendation does not advocate patent ownership of AI systems. Since innovative human activity cannot be the parameter for determining initial ownership of patents on purely AI-generated inventions, the law must develop a set of different criteria ( cf . Sect. 3.3.2 ). This exercise is all the more worthwhile because its results are key for many an AI/IP setting: where increasing prowess and independence of AI systems render it difficult to assign legal rights to their output based on human inventorship, creatorship, or similar concepts, other parameters must step in to safeguard an allocation that is economically sound and apt to fulfil the goals of the IP system.

This is not to ignore the fact that a large part of the inventions made today and in the near future result (also) from a human contribution substantial enough to acknowledge human inventorship without difficulties. The pertinent part of the above Recommendation does not deal with AI-assisted inventions but with truly AI- generated ones. These hard cases may be rare – some would even say: non-existent – at present. But their relevance seems very likely to increase, and the law should be prepared by then.

Assessing the novelty of an invention against the state of the art researched with the help of AI systems, and only accepting steps as inventive which so appear from the perspective of a PHOSITA equipped with an ordinarily skilled AI system, will most probably raise the bar for patent protection. Footnote 12 In their contributions to the Project, some stakeholders voiced the concern that, as a result, only resourceful players, commanding exceptionally performant AI systems, may be able to acquire patents in the future. While we acknowledge the theoretical validity of this point, we do not see any empirical evidence that such a development is underway in larger sectors of the economy. Furthermore, it has always been the case that greater resources – such as laboratories with superior equipment, larger research departments, the ability to pay high wages to attract the best researchers, etc. – increased the chance of a market player to accumulate patents. In sum, we do not currently think that unlevel-playing-field concerns should prevent the integration of AI system capacities into the patentability assessment.

3.1.2 Human Authorship in Copyright Law

3.1.2.1 recommendation.

The principle of human authorship should prevail in copyright law – at least in the droit d’auteur systems. Hence, copyright protection should not be extended to works of literature and art created by an AI system without a human contribution even if they amount to a creation in the sense of copyright law. This result is achieved by applying the established criteria of human creation. At the same time, this allows for granting copyright protection for content that has been collectively created by an AI system and a natural person provided that the human contribution is sufficiently creative.

3.1.2.2 Background

Intellectual property law is traditionally based on the idea of one (or several) human creator(s). That is especially true for copyright law, at least for the droit d’auteur systems. In these systems, the idea of a human author is firmly rooted in many key provisions.

The human author plays a key role in the conditions for the protection of a work. According to settled case law of the ECJ, the concept of a work entails an original subject matter which is the author’s own intellectual creation. Footnote 13 Accordingly, there is no work without an author and such author must always be a natural person. Footnote 14 The situation is similar in Swiss law which only protects intellectual creations with an individual character (Art. 2(1) Copyright Act). The requirement of the intellectual creation means that only works created by natural persons can be protected by copyright. Footnote 15 The link of the intellectual character to a human author may be less direct but it is no less important; according to the key test, the requirement of individual character is met if no other individual would have created an identical or highly similar work. Footnote 16 The human being is also the key figure for copyright ownership as the original rightholder is always the author, i.e. the natural person who created the work. Footnote 17 In addition, droit d’auteur systems provide for a series of personality rights, such as the right to recognition as the author and the right to determine the author’s designation, Footnote 18 the right to decide on the first publication of the work, Footnote 19 the right to decide if the work may be altered and/or used to create a derivative work, Footnote 20 and the right to oppose a distortion of the work. Footnote 21 Finally, all copyright systems calculate the term of protection starting from the death of the author. Footnote 22

While some copyright systems have granted copyright protection for machine-generated content for years, Footnote 23 the droit d’auteur systems are hardly suitable to do so. A fundamental shift in these systems would be necessary to accommodate protection of machine-generated content by rethinking and adapting the provisions on the requirement of protection, the initial rightholder, the granting (and exercising) of personality rights and the duration and calculation of the term of protection. However, there are no convincing reasons why this should be done. While we acknowledge that there are some arguments for granting copyright protection to AI-generated works, these arguments seem rather weak. Most importantly, it may not necessarily be convincing to treat works that seem to be similarly “creative” in a fundamentally different way, just because one has been produced by a machine and the other by a human being. However, works of literature and art are public goods and granting exclusive rights to such goods requires a sound justification. Given that all other rationales for the justification of copyright protection (namely personality rights and the labour theory) are closely linked to human creators, the only potential rationale for granting copyright protection for machine-generated works is the need to provide incentives for creative activities. However, once an AI system has been developed, it can produce content such as text, images, music, films, and the like at almost zero marginal cost. While it may be important to grant some form of IP protection for the AI system, there is no need to incentivize the use of these systems by granting copyright protection to their output. Footnote 24

There are other instruments for protecting output that has been created in a fully automated manner and lawmakers (and courts) could improve such instruments, if necessary. Most importantly, the “copy paste” and use of AI-generated content may be captured by unfair competition law, namely by applying the general clause of most European unfair competition acts that allow to capture imitations and the copy-pasting of third-party content if certain conditions are met. Footnote 25 In Switzerland, Art. 5(c) Unfair Competition Act seems to be a good match. This provision captures all instances of taking over and exploiting another person’s marketable work product by means of a technical reproduction process without reasonable effort of the person or company that takes over and exploits the work product. Should unfair competition law prove to be insufficient to accommodate justified needs for protection, lawmakers could consider creating specific neighbouring rights for content generated by AI systems. Footnote 26 From today’s perspective, however, there seems to be no need for such new rights. Footnote 27 In addition, creative software output of AI systems – potentially including settings where an AI system creates another AI system – may be covered by the software protection regime envisaged in these Recommendations ( cf . Sect. 3.3.1 ).

In addition, it is important to bear in mind that denying copyright protection to AI-generated content does not mean that the producer cannot exploit such content on the market. Most importantly, such content can be protected by access restrictions and other technical measures, e.g. digital watermarks, to ensure that others cannot use it without paying a remuneration.

3.2 Consideration Recommendations

3.2.1 corporate iprs, 3.2.1.1 recommendation.

The law should consider allowing corporations and other legal entities to acquire initial ownership of (AI-generated) patents and patent-related IPRs (e.g. utility patents, but not copyrights), at least in cases of AI inventorship.

3.2.1.2 Background

The discussion whether legal entities should be able to acquire the right to a patent and – following the grant of the patent – initial patent ownership is not new. So far, and though dissenting ( de lege ferenda ) views always existed, Footnote 28 the prevailing response has been negative, Footnote 29 not least because today’s patent laws give much weight to a personalistic notion of inventorship, according to which there cannot be an invention without a (human) inventor. Footnote 30 When, however, an invention is generated by an AI system, this conception seems much less convincing. The assignment of legal rights and economic benefits relating to such inventions relies less on personalistic criteria. For instance, companies, and not their employees, will frequently bear the costs for building an inventive AI system and they, not their employees, will exercise legal and economic control over these systems. Insisting on human initial patent ownership in such settings risks distorting a coherent assignment of legal and economic rights to non-human inventions. The law should, therefore, consider relaxing the rules that allow for human initial patent ownership only. Footnote 31

3.2.2 Need for New IPRs Doubtful

3.2.2.1 recommendation.

Currently, there is no need to establish new sui generis IPRs for AI output. Neither current research insights nor current market realities suggest a need for new (sui generis) IPRs (including neighbouring rights) for innovative or creative AI output. Unless future research, including work done as part of the AI/IP project, proves the opposite, lawmakers should abstain from establishing such new types of IPRs.

Furthermore, there are currently no sound reasons for a two-tiered system of differing protection for human and AI inventions and creations. On the contrary, such a system seems prone to generate delimitation predicaments and to entice concealment or deliberate distortion of the genuine innovative process.

Such restraint does not exclude improvements of the current protection regime, for instance, in order to better accommodate software (including AI systems) produced by an AI system ( cf . Sect. 3.3.1 ), the way data rights are allocated, or the framework for trade secret protection.

Should future AI systems generate inventive output at a high rate and in a process that clearly lacks human inventive contribution, the situation may have to be reconsidered. Patent-like protection for such output, which is however weaker than the protective level of current patents, may become a preferable mechanism for allocating exploitation and transaction rights while avoiding over-protection.

3.2.2.2 Background

In academic discourse, proposals have been made for new types of intellectual property rights to protect the innovative or creative output of AI. Footnote 32 Sufficient IPR protection for the AI systems that generate such output seems, on the other hand, less of a concern. Our Patent Law Inventorship Recommendation ( cf . Sect. 3.1.1 ) helps to guarantee the structural availability of IPR protection for technical AI inventions. According to our Authorship in Copyright Law Recommendation ( cf . Sect. 3.1.2 ), restricted copyright protection for creative AI output constitutes not a failure but a virtue of the IPR system. A consensus against the establishment of distinct protection systems for human and AI-generated innovations has already been formed. Footnote 33 Mainly for the reasons stated in the above Recommendation, we support this position. Regarding inventive/creative output or other instances of valuable output generated by AI systems without substantial, innovative human contributions, neither the AI/IP Project nor – to our knowledge – other empirical or economic research ( cf . also Sect. 3.3.3 ) has proven current market failures or insufficient innovation incentives that necessitate the creation of new IPRs. Growing new plants in the already lush garden of IP rights comes at a cost – e.g. anti-commons problems, Footnote 34 transaction costs or interaction issues between the various IPRs – that should only be incurred based on solid evidence of their necessity. Putting another dent in the enthusiasm for new sui generis rights, none of the new IP rights introduced in the last 50 years has proven a real success. This applies, in particular, to the protection of databases through a sui generis right Footnote 35 and the legal protection of topographies of semiconductor products. Footnote 36 Even though it seems premature to assess the impact of the new neighbouring right for the protection of press publications, the chances of success of this new IP right seem doubtful as well. Footnote 37

We cannot, however, exclude the possibility that this picture may change in the future. New ways of detecting and deciding, with sufficient certainty, whether a human or an AI system generated a particular innovation may remove some qualms regarding a two-pronged protection system for human and AI inventions and creations. Extending patent protection at its current level (duration, scope of exclusivity, etc.) to AI-generated inventions may become an unacceptable impairment of dynamic efficiency and freedom to do business, if previsions come true that powerful AI systems will swamp the markets with innovative output at high rates and high quality. Then – and only then – should the law consider conceptualizing new types of limited IP protection, mainly for technical inventions. Such IPRs could combine the transactional benefits of a clear allocation of rights, Footnote 38 incentivization for the creation and maintenance of high-quality AI-systems, Footnote 39 disclosure of innovations to the public, and – for instance, through suitable licensing mechanisms – balanced access to protected content by other market participants. Utility patents do not necessarily provide a blueprint for such AI-specific, “narrow” IPRs, but at least they show that varying levels of protection for technical inventions is a concept that is workable and familiar to the IP system.

3.2.3 Broadened Research Exemption

3.2.3.1 recommendation.

Subject to further research, IP and data law should likely stipulate clearer and more permissive protection carve-outs to facilitate development, training, and testing of AI systems.

The development, training, and testing of AI systems requires the processing of very large amounts of data. Given the extremely broad definition of personal data in data protection laws, Footnote 40 much of these data are to be qualified as personal data and their use is thus subject to the provisions of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and other data protection laws. In many instances, the data used by AI systems are digital representations of works of literature and art. This is usually the case when AI systems are to recognise or produce text, images, music or films, and therefore need to be trained with corresponding copyright content. In addition, many data used by AI systems will be protected by the sui generis database right. Trade secret or patent protection, for instance, can also come into play. Using data for the development, training, and testing of AI systems may thus violate the provisions of the GDPR or infringe copyrights, the sui generis right in databases, or other intellectual property rights.

Patent and copyright laws, as well as other IP protection systems, contain provisions that allow the use of protected content for research and development, but it seems doubtful whether the existing exemptions are sufficiently broad and homogeneous across jurisdictions to allow for the desired use level of such content by AI systems. Footnote 41 The Database Directive, for instance, does not contain any research exemption for the sui generis right. European lawmakers should thus consider introducing broader research exemptions in copyright law, and creating a research exemption for the sui generis right in databases. Footnote 42

While the GDPR contains provisions that amount to a potentially quite broad research exemption, Footnote 43 it remains unclear if and to what extent this exemption can be applied to privilege the processing of personal data for the development, training, and testing of AI. Given the key importance of data (including personal data) and the lack of harm caused to data subjects by the processing of personal data in the development, testing, and training of AI systems as such (note though that harm may be caused to data subjects by using AI systems Footnote 44 ), we recommend that the GDPR’s research exemption should be interpreted in a way that facilitates such processing. Ideally, this interpretation should be explicitly promoted in an Opinion of the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) to provide legal certainty.

3.2.3.2 Background

Today’s IP and data protection laws were developed prior to the rise of AI. Footnote 45 Although patent, copyright, and data protection laws contain research exemptions, it is unclear if and to what extent these provisions can capture the use of personal data and IP-protected content if the respective data are used for the development, training, and testing of AI systems.

Regarding copyright law, the two exceptions for text and data mining introduced by the Digital Single Market (DSM) Directive Footnote 46 may mitigate the problem. The mandatory exception, however, only covers uses for scientific research by research organisations and cultural heritage institutions, thus excluding text and data mining in a commercial context. Footnote 47 The non-mandatory exception that also applies to commercial uses only covers cases in which text and data mining has not been expressly preserved by the rightholder. The scope of these exceptions is therefore limited. Moreover, the DSM Directive does not mention the use of text and data by AI systems. It is therefore unclear whether the exceptions also cover the use of copyright content for the development, training, and testing of AI systems. The recently introduced research exemption of the Swiss Copyright Act is substantially broader, covering all research and development (including for commercial purposes) and all reproductions that are necessary for technical reasons. Its deliberately broad wording should also cover the use of copyright-protected content by AI systems, both in a research and in a commercial setting.

The sui generis right allows the maker of a database to prohibit the extraction and/or re-utilization of the whole or a substantial part of the contents of a database. However, insubstantial parts may be used by lawful users of the database. While this certainly limits the restrictions of the sui generis right with respect to the use of data by AI systems, one must assume that there are many cases in which it would be useful to extract and re-use all or substantial parts of a database. Thus, the sui generis right imposes relevant restrictions on the use of data by AI systems. As opposed to copyright law, the Database Directive does not even contain an exception for text and data mining. In consequence, adding a broad research exemption to the Directive that also covers the use of data for the development, training, and testing of AI systems seems to be key. Importantly, such an exemption would not confer a standalone right of access to the data contained in a database. It would merely allow the use of data for research purposes if access to such data has already been granted, most often on a contractual basis and against remuneration.

European data protection laws, especially the GDPR, create significant obstacles to the use of data by AI systems, such as the principle of data minimization and purpose limitation, as well as the need to provide a legal basis for the processing of personal data. Footnote 48 Additional barriers stem from restrictive rules on the transfer of personal data to third countries and the increasingly impractical distinction between personal and non-personal data. While the GDPR contains provisions that potentially amount to a quite broad research exemption, Footnote 49 it remains unclear if and to what extent this exemption can be applied to privilege the processing of personal data for the development, training, and testing of AI. However, a suitable application of the research exemption can only be a first step. As outlined below, further research is needed to develop a suitable data usage framework. Footnote 50 In addition, clear and comprehensive data access and/or data use rights Footnote 51 should be established, regarding both personal and non-personal data, to facilitate the development, training, and testing of AI systems.

At the same time, protection carve-outs must not become a carte blanche for IPR infringement. Generative art (art with and through AI) is, for instance, a field in which legal rules need to carefully balance access to and protection of IPR-protected content. AI is a powerful tool for creating works such as films, music, or architectural designs. Such tools are already being offered to the general public for free. The conditions for use of such tools and their output (including sale as non-fungible tokens) vary greatly and can have important effects on the operating modes and business models of the artistic community. Some developers are not sufficiently aware of, or are not willing to abide by, copyright protection rules. Others miss out on advantageously structuring the use of their tools through contractual arrangements. Working, together with stakeholders, from this situation towards a more appropriate legal and factual framework for generative art constitutes a worthy task both for IP offices and for the general discourse on AI protection carve-outs.

3.3 Research Recommendations

3.3.1 new software protection regime, 3.3.1.1 recommendation.

Future research should develop a novel IP protection regime for software that could replace today’s two-tiered approach.

The current IP system does not provide a convincing protection regime for software. The interaction of its main instruments, copyright and patent protection, is far from ideal. The regime has evolved over time, driven by the approach to somehow incorporate software protection into the traditional IP system. However, software differs in important respects from both works of literature or art and from technical inventions. Fitting it into copyright and patent law thus necessitates many compromises. Software produced and employed by AI systems is a recent challenge of particular importance to today’s approach. Therefore, the development of AI systems makes it more urgent than ever to remedy the deficiencies of the current regime for software protection.

The dual system combining copyright and patent protection should be rethought and possibly replaced by a single IPR for software (including AI systems). Such a regime may combine a very limited sui generis protection (regarding both substance and duration) for unregistered software with a stronger protection for software registered in a software register. The granting of a strong IP right could come with (source code) disclosure requirements. Better tailored to promote innovation and to avoid overprotection, such a system may also allow for the closing of current protection loopholes, e.g. regarding complex, highly innovative modelling software.

Given the huge economic importance of software, the implementation of such far-reaching changes in its protection regime resembles open-heart surgery. These changes cannot be undertaken without thorough prior research and discussion. Such research must be interdisciplinary, involving not only legal scholars but also computer scientists and economists. All stakeholders’ (software developers, industry, IP offices, the open source community, and key user groups, etc.) views need to be collected and novel protection approaches need to be tested in a discourse with them.

Given the existing framework of IP treaties, a novel software protection regime could hardly replace the current system over night. But novel approaches could be introduced at a national and regional (e.g. EU) level alongside the existing regimes. If these approaches prove workable, they may well replace the current protection regimes de facto, namely if companies stop applying for software patents and enforcing copyrights. Traditional approaches for software protection may either continue to (formally) exist or be abandoned altogether at a later point in time.

3.3.1.2 Background

Software has always been a sort of outsider among the subject matters of the IP system. The protection regimes that are applied to computer programs were developed long before software even existed. As it seemed virtually impossible to create an entirely new IP right to capture software in the 1980s and 1990s, national lawmakers and international organisations had no choice but to accommodate software in the existing IP regime. The obvious choice was copyright as it came with a series of benefits, the most important ones arguably being that the existing international regime allowed for an almost worldwide protection without the need for application, examination, registration, and payment of fees. In addition, the inclusion of software in patent law was blocked (at least) for the member states of the European Patent Convention as Art. 52(2)(c) EPC states that programs for computers cannot be considered inventions. The “linguistic approach”, focussing on the expression of algorithms in the source code, permitted software to be treated similarly to works of literature and art, Footnote 52 thus allowing copyright protection. With partial amendments to copyright law, e.g. on decompilation Footnote 53 or shortened protection terms, Footnote 54 some steps were taken towards a software-specific protection regime, but without accomplishing this task.

Irrespective of this integration process, businesses also sought the benefits of patent protection for their software. In the US, such patents were granted on a relatively broad basis following a series of Supreme Court decisions in the 1970s and 1980s, culminating in Diamond v. Diehr in 1981, Footnote 55 and subsequent decisions by the Court of Appeal for the Federal Circuit. Footnote 56 Europe remained reluctant, given the provisions in the EPC that excluded patents for computer programs as such (Art. 52(2)(c) and (3) EPC). While patents were (and still are) unavailable for mere computer programs, they were eventually granted for so-called “computer-implemented inventions”. Footnote 57 Over time, the more permissive US and the more restrictive European approach have converged to a certain extent. Inter alia , the US system became more stringent, and moved much closer to the European approach, with the Supreme Court’s Alice decision. Footnote 58

As a result of these historical developments, software can be protected by both patents and copyrights in the major jurisdictions. While it is not uncommon for several IP rights to protect a given object – e.g. copyright, design, patent, and trade mark rights to protect the design of a car – it is quite unusual for a given subject matter category to be explicitly covered by more than one IP right. Not surprisingly, this two-tier system of protection leads to contradictory results. For instance, despite the expiry of patent protection after 20 years, previously patented software does not fall into the public domain but remains protected by copyright for a much longer period of time.

A major problem of the current software protection regime is the fact that neither copyright nor patent law are well suited for this subject matter. Software is different from both technical inventions and works of literature and art. IP protection granted to it should be keyed to these particularities. For example, many software products (e.g. operating systems) cannot be substituted by others because they have become de jure or de facto standards. Software products need to be integrated into a (usually pre-existing) framework of hardware and software, which requires interoperability that can only be ensured if application programming interfaces (API) are provided or – where necessary – lawfully developed through reverse engineering. In digital economies, software assumes a sort of infrastructure role for ever more products and services. Also, in view of these characteristics, the strong protection (duration, degree of exclusivity, etc.) granted by the combination of copyrights and patent rights seems problematic at least for certain types of software (e.g. update patches). Licensing transactions ensuring freedom to operate are hampered by difficulties in determining software ownership and by multi-owner IPR thickets. Fragmented statutory rules and market developments, such as the “open source” movement, have patched some of these issues. Others have led to highly complex and year-long proceedings before competition authorities. Footnote 59 A well-tailored protection framework, including built-in limitations that secure access rights where needed, promises many advantages over these makeshift approaches. It becomes all the more desirable with a view to AI systems consisting, in essential parts, of software and generating large-scale software output the protection status of which is far from evident. Footnote 60

While it seems that software developers and the industries producing and using software have learned to cope with the current software protection framework, important issues remain unresolved. Moreover, the mere fact that developers and the industry have learned to make the best of the current software protection regime in no way precludes that a much better system could be created, i.e. a system that leads to faster and cheaper innovation and raises fewer competition issues.

3.3.2 AI Inventorship and IPR Allocation Parameters

3.3.2.1 recommendation.

Future research should develop a comprehensive grid for the allocation of entitlements resulting from innovations generated by AI systems.

As a key consequence of loosening the ties between the generation of innovative output (by AI systems) and the ownership of resulting IPRs (by natural or legal persons), research must work out a more comprehensive grid for the sound allocation of IP entitlements resulting from innovations generated by AI systems. This concerns a broad range of IPRs (e.g. patents, utility patents, design rights, and new forms of software protection), as well as settings where complementary innovative activity is undertaken by AI systems and human individuals or teams.

3.3.2.2 Background

An appropriate allocation of AI output-related IPRs to natural or legal persons sets the conditions for achieving the IP system’s goals, particularly the incentivization of innovation and the fostering of IP transactions – licensing in particular, but for instance also the use of IP as collateral in M&A and venture capital transactions – which help to disperse and implement protected content. The conduct-steering effect of liability as well as clear responsibilities in the IP system’s self-protection through the enforcement of IPRs against infringing use are further allocation-related benefits. Allocating rights and responsibilities to AI systems themselves is not an option due to these systems’ lack of personality in the legal sense.

There is already some discussion about parameters for allocating IPRs resulting from AI innovation. Footnote 61 Among the main candidates are creatorship of or investment in the output-generating AI system, control over the system at the time of innovation, and responsibility for task and output selection (choice-making). Furthermore, some jurisdictions have adopted statutory rules that assign – be it for AI settings or at a more general level – initial IPR ownership to persons other than the factual inventor. Footnote 62 However, these allocation elements do not yet form a sufficiently comprehensive framework. The additional questions such a framework would have to answer are manifold. What, for instance, is the – possibly sector-specific – hierarchy or relative weight of several applicable allocation parameters? In case different persons fulfil different allocation criteria, does this always result in co-ownership Footnote 63 or do certain allocation parameters (sometimes) outweigh others? For settings in which co-ownership turns out to be the result, are IP law’s present rules on co-ownership appropriate, even though there are no non-economic inventor/author rights to be protected? Assuming that certain groups of (co-)rightholders yield to requests that they waive their position, e.g. for fear of otherwise losing downstream clients, Footnote 64 should the law accept such contractual arrangements?

Arranging the answers to such questions into a suitable allocation regime requires profound research. Such research needs to include legal, economic and technological aspects, including an incentives analysis ( cf . 3.3.3) for accommodating novel allocation approaches.

3.3.3 Revisit Incentivization Necessities and Ownership Approach

3.3.3.1 recommendation.

The IPR system must not mechanically extend its traditional incentivization rationale to innovative AI output. AI systems themselves do not require incentivization. Effective and efficient incentives for natural/legal persons to engage in the development and use of high-quality AI systems, as well as in the implementation of and transactions over their innovative output, need not necessarily parallel traditional IPR incentives for human innovativeness. Traditional notions of ownership may have to be rethought and protection may be oriented more towards securing monetary rewards and freedom to operate than towards non-economic ownership rights.

3.3.3.2 Background

Economists point out that incentivization of AI outputs as such may be unnecessary or even detrimental, whereas it may drive innovation and dissemination to incentivize the commercialization of such outputs (including transactions over them) and the development of AI systems that generate them. Footnote 65 In view of the potentially high innovative output of (future) AI systems, granting full-fledged IPRs to each such output may, in particular, generate overcompensation and excessive IPR thickets. Research, in which economics looms large, must therefore explore incentivization exigencies and dynamics in the AI innovation field. It is crucial to avoid the unwanted effects of over- or under-protection on dynamic efficiency. Such research must also explore whether, and in which ways, the growing relevance of AI systems and data change the role IPRs play for businesses, both in daily practice and at a strategic level. Footnote 66

3.3.4 Data Usage Framework

3.3.4.1 recommendation.

Future research should develop a legal framework focusing on access, sharing and usage of (personal and non-personal) data for the common good while providing a suitable protection of privacy and workable means to protect individuals against harm resulting from data processing.

Next step research should specify legal cornerstones for enhancing the access to, usage and sharing of (personal and non-personal) data for the development, training, and testing of AI systems. Topics include novel approaches to data (protection) law, common data spaces, data pools, interoperability requirements, technical standards regarding syntax and semantics of data, and the (non-)mandatory, sector-specific licensing of data portfolios to AI users/developers on a FRAND basis.

These approaches must apply both to personal and non-personal data since access to and use of both types of data are key conditions for the development, training, and testing of many AI systems. Further research is needed on whether and to what extent the usage of personal data by AI systems risks engendering an infringement of data protection laws or personality rights, such as the right to protection of privacy. A potential way forward could be an in-depth analysis of the scope of current research exemptions in data protection laws (particularly the GDPR) to assess if these exemptions can be applied broadly to cover the usage of personal data by AI systems. But research should also consider entirely novel approaches that go beyond the idea of an all-encompassing regulation of the processing of personal data (as in the GDPR) but rather provide a workable protection of privacy and means to protect individuals against harm resulting from the processing of personal data (e.g. manipulation and discrimination) while opening up the usage of personal data for the common good. Footnote 67

This research must include both an interdisciplinary and an intra-disciplinary component. Obviously, workable data transaction frameworks cannot be conceived without the input of computer and data scientists. But even from a purely legal perspective, there are manifold issues that need to be considered beyond IP and data law, such as contract, competition and procedural law. Equally, the analysis of pertinent business models promises to be very fruitful, including collaboration between holders of large data sets and controllers of powerful AI systems.

In addition to opening up access to and use of data, in-depth research is needed to clarify the legal consequences if an AI system has been developed, trained, or tested with data that have been accessed or used unlawfully. Should this “infect” the AI system in some way, even if the system does not contain the unlawfully used data? Should the consequences be the same regardless of whether the data were used for the development, the training, or the testing of an AI system? And, should it matter whether vast or small amounts of data have been used in an unlawful way – possibly even just a single data point?

3.3.4.2 Background

Data are a key resource for AI operations, especially for AI systems that are based on machine learning. But use of and access to data are often restricted for various reasons. While the use of non-personal data is much less regulated and thus largely permissible, European data protection laws, especially the GDPR, impose significant restrictions on the use of personal data, the most important ones being: The principle of data minimization which requires that the processing of personal data be adequate, relevant and limited to what is necessary in relation to the purposes for which the data are processed; Footnote 68 this principle may inhibit the use of personal data for the training, and testing of an AI system. The principle of purpose limitation according to which data may only be collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes and not further processed in a manner that is incompatible with those purposes; Footnote 69 often, personal data would be a great resource for the development and training of an AI system, but that system might have a purpose which is different from the purpose for which the data were collected, e.g. geo-localization data collected by telecom service providers that could be used to train an AI system that helps to fight traffic jams and to balance public transportation occupancy. A major barrier for the use of personal data by AI systems is that some data protection laws, namely the GDPR, require a basis for the lawfulness of any processing of personal data, the most important ones being the data subject’s consent, Footnote 70 an overriding legitimate interest of the controller, Footnote 71 the need to process personal data for the performance of a contract to which the data subject is a party Footnote 72 or the need to process data for compliance with a legal obligation. Footnote 73 Although the range of possible reasons for the lawfulness of processing is quite broad, such a basis will often be lacking for the use of personal data for the development, training, and testing of AI systems.