A Critical Evaluation of Educational Ethics

- Posted February 9, 2023

- By Ryan Nagelhout

- Moral, Civic, and Ethical Education

- Teachers and Teaching

Education is a field full of choices, and not just for students. Teachers, administrators, and parents are also faced with an endless array of decisions to weigh among an ever-changing educational landscape.

Navigating that landscape requires an understanding of the impact of those choices. Professor Meira Levinson knows that moral quandary well, both as an educator and researcher. Through the development of case studies, Levinson and her peers in the field of educational ethics have developed methods to evaluate situations where educators grapple with issues of inequality, morality, and uncertainty.

In recent years, Levinson has spearheaded EdEthics at HGSE, developing projects with the help of a number of collaborators. The latest is an online class launching this spring, Promoting Powerful Ethical Engagement with Normative Case Studies , co-taught by Levinson and doctoral student Ellis Reid , and co-designed by Sara O’Brien, Ed.M.'19; Ariana Zetlin, Ed.M.'20; and HGSE's Teaching and Learning Lab (TLL). EdEthics is also hosting a field-launching conference at HGSE in May, designed to help build the field in a model similar to bioethics.

Below, Levinson discusses the growing field of educational ethics and how the new class and other projects will help expand the impact ethical thinking has in the classroom and beyond.

What is the goal of your new course, Promoting Powerful Ethical Engagement with Normative Case Studies?

I was most interested in creating opportunities for people to have complex conversations about the ethical dilemmas we faced in policy and practice. And yes, it is explicitly focused in areas of ongoing uncertainty where I don’t think there is a single, right answer. I think there may be wrong answers. And there are worse answers and better answers, so it’s not as if this is a stance that’s all about being relative, or everybody’s entitled to their own opinion. That’s not what’s going on here. And I think it can be useful to collectively discover or identify or explain wrong answers, right? But even once we say “oh well these are worse answers,” we still have a constellation of better answers.

We create solely around hard ethical choices where we ourselves do not know what the right answer is. And if we think that there is an answer, or the right way to see the problem, then we’ll write an article about it. And so that's actually been very useful as well. We don’t only write cases, we also write philosophical articles.

With EdEthics, part of what you are doing is framing long-standing educational issues within an ethical lens. How did you start approaching things in this way?

When I was an eighth-grade teacher, I faced lots of ethical questions in my work. Really, on a pretty daily basis trying to figure out what was the just thing to do. What was the right thing to do? What was the ethical thing to do? I was thinking about really basic questions like, I have kids with lots of different needs in front of me and I can’t fulfill all of them simultaneously, so how do I figure out whom to prioritize? And how? And why?

"I wanted to make it possible for HGSE students but also others out in the field, to have complex conversations about the ethical dimensions of our work in education and to recognize that ethics is central to what we do."

If I have a disruptive student in my room and it’s really annoying, in some ways, yes, they’re choosing to be disruptive. But they’re 13, they’re 14, right? We don’t want any of these choices that they’re making right now to have any impact on the shape of their lives. … But you also want to teach them a sense of responsibility, you want to teach them actions have consequences. You want to teach the other kids that actions have consequences. What they’re doing is disrupting the learning for the other kids. And so, you owe the other kids the opportunity to learn.

Answering those questions requires an understanding of a variety of issues and balancing the impact of multiple outcomes. How do educators gain the tools to help tackle these big questions in a productive way?

These really, really concrete questions were ones that I thought, well if anyone should have an answer to these from an ethical perspective, I should. I have a DPhil in political theory from Oxford. I wrote a dissertation about what the aims of education should be in a liberal democratic society and how we should achieve those. And I was just stuck.

I looked around and I could not find stuff that would answer my question. A lot of things had been written about what do you do when you have someone trying to pull out of a particular lesson. There’s lots of stuff about some very specific questions. But the day-to-day quotidian stuff of teaching? There just wasn’t much there except stuff that was really, really rule-bound. Stuff like, don’t steal the copy paper. Don’t sexually harass kids. And that’s true: don’t steal the copy paper, don’t harass kids. But that doesn’t help you figure out other stuff. The very concrete but also really big ethical questions. That was part of why I started the site Justice in Schools .

A lot of the case studies you’ve written seem to be about big problems that don’t really have clear solutions with lots of opinions on both sides. Why is it important to evaluate these issues critically?

When I finally came to the Ed School as a faculty member in 2007, I had a whole series of students come through my office and say, “Professor Levinson, we are so glad that you’re here. I believe in educating for social justice.” And I would say “Great!” And then they would think it was clear that by telling me they cared about social justice that they had also told me what their stance was on charter schools, on high-stakes standardized testing, on teacher accountability measures or value-added measures for teachers, on project-based learning — on lots of stuff that was being debated in 2007.

And I have no idea what they thought about those things, right? They could be a total advocate for charter schools because they believed in autonomy and in some kind of greater measures of local control. You could believe that these districts are failing kids and that these charters might be great. Or you could be totally against charters because you thought that schooling should be directed in a public and democratic way and you were worried about issues of equity. Students would come in with all kinds of these different views but it never occurs to them that the opposite view might also be an ethically held one that was actually driven by values. Or even by some of the same values.

Seeking answers to those questions, then, was one part of your goal at HGSE in developing EdEthics?

I wanted to make it possible for HGSE students but also others out in the field, to have complex conversations about the ethical dimensions of our work in education and to recognize that ethics is central to what we do.

Our work always has ethical balance, and also at the same time helps us understand that people whose policy prescriptions we might disagree with often are driven by values. It’s not that they are totally unethical, it’s not that they hate kids or are captured by the teachers’ unions or textbook lobby. They’re not rapacious, racist, or are necessarily defenders of the status quo. Sometimes that’s what’s going on, but oftentimes what’s going on is that people really care, deeply, about the values that they’re trying to live out in their daily life and they’re trying to put into practice.

HGSE has a very strong leadership focus and policy focus. Over time I became interested not only in the kind of quotidian, ethical dilemmas we face in the classroom as teachers but also the ethical dilemmas as you go up the scale — questions about what principals face, what do school boards face? What do curriculum developers and designers face? What do we think about the state legislature, things like that. So my interest in ethical question about education expanded that way too.

I’m curious how you select topics for case studies. Is the goal to find something universal to talk about with a wide variety of students? Is it more about recency and what’s newsworthy, or maybe just what you think could bring about the best discussion?

The Promoting Powerful Ethical Engagement course is focused on helping people learn how to write normative case studies for their own context. So in that respect, we don’t have any preconditions about what they write about. We want them to write about whatever dilemma feels most salient and important to them to address in their context. We do have a lot of guidance in the course about how to identify and evaluate dilemmas, so, what’s in the news can actually be really important. This online course actually comes out of a workshop that we held in the summer of 2021 with about 15 people from around the world who had used our normative case studies in their own work but they wanted to develop normative case studies that were more targeted to their own context thanks to support from Radcliffe through one of their accelerator workshops.

Being COVID times, we did this online. But it meant we had participants from Kenya, mainland China, Hong Kong, Australia, Germany, the United Kingdom, Canada. Mexico. All over. Many of these cases were very real-time dilemmas. For example, one team in Germany wrote about a social studies teacher trying to figure out how to deal with a student who’s been captivated by the German equivalent of QAnon. And who’s very smart and very passionate, and very well-spoken, and he can get on a roll in class and start spewing this stuff and the other kids are like “Oh, yeah, that makes sense. You’re right.” And she’s like, “No!.” So that’s a very of-the-moment case.

There’s another case in Kenya about a fairly recent requirement that students who graduate from primary school automatically get to go to secondary school, which is clearly really important for improving access and equity. But many kids board at these secondary schools because they’re too far away from their homes to be able to go on a daily basis. And these schools just don’t have the space, they don’t have the dorms. They don’t have the teachers, they don’t have the physical plan. And so she wrote a beautiful case about questions of access and opportunity and quality in trying to implement Kenya’s secondary school access curriculum. Other people who participated wrote about things that were somewhat more evergreen.

You’re written a lot about schooling amid the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had a huge impact on education. As an ethicist, is there anything to be learned when public consensus moves clearly away from ethical thinking?

COVID revealed to many people what experts in the field already knew, which is that our social safety net for children is very thin and full of gaping holes. And we just apparently aren’t willing to support kids in terms of their health, their nutrition, their mental health, their dental care, their learning, their housing. There are all sorts of ways where we don’t help as much as we should. And so in lots of ways, we just don’t value children, and that came out during COVID and has come out many times before and unfortunately will continue to come out.

But what about educational ethics? Well, given the lousy choices that we did make and have made and, unfortunately, look as though we’re going to continue to make, I think that is a reason to have ed ethics as a field that can speak up and have a broad array of people who have done the kind of thinking we need ahead of time so that when questions of public policy and practice come up and we have concerns we can have the tools to hand immediately to speak out about these things. So that’s one reason that it’s important to me to start a field of educational ethics so we have that kind of broad base of expertise and range of experts — this is not just about philosophers, it’s not just about historians, it’s not just legal experts, not just academics. It’s not just in the United States, it’s all over. We want people in all sorts of fields, in all sorts of positionalities who are able to talk about the ethical dimensions of the work and offer guidance about it in real time.

As we are able to develop educational ethics as a field, we will engage in more ethical behavior. It’s not only about hard problems. It’s also, in fact, about being able to say “This is an ongoing question. Let’s figure out what the best answer is to that question,” and have that at hand.

The latest research, perspectives, and highlights from the Harvard Graduate School of Education

Related Articles

Education, Truth, and the Future of Democracy

When We Teach Climate Change

The Questionable Ethics of College Students

Schools Are Full of Ethical Dilemmas. Can Ethicists Help?

- Share article

(Disclosure: The author spoke at the conference described in this story as an invited panelist whose travel expenses were paid by Harvard University. The panel he served on is not featured in this story.)

From responding to public pressure over school mascots to navigating parent complaints about LGBTQ-themed library books, the staff of the 3,200-student Guilford, Conn., school district must confront a steady stream of ethical quandaries.

So, Superintendent Paul Freeman decided to call in the experts.

“It doesn’t matter if you’re an elementary teacher supervising indoor recess or a physics teacher at the high school, things will come up,” Freeman said earlier this month at a Harvard University conference intended to spur the formal establishment of a new field of educational ethics. “We were looking for somebody who could help teachers feel competent and confident in having these conversations.”

That person turned out to be Harvard political philosopher Meira Levinson , the driving force behind the effort to help schools better manage vexing situations in which it’s impossible to satisfy everyone’s wishes without compromising someone’s core values. The goal is less about giving recommendations than encouraging thoughtful deliberation around general principles that can be applied to real-life situations as they arise.

Professionals in numerous other fields work with ethics experts in such a manner. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, hospitals and public health agencies had bioethicists on call as they worked through wrenching decisions about allocating ventilators and distributing finite supplies of vaccines. In the K-12 world, however, school boards, superintendents, and state education leaders were often on their own when making similarly tough calls about reopening schools and requiring masks—not to mention confronting a raft of other concerns around everything from bathroom access to artificial intelligence.

The barriers to Levinson’s vision are numerous. At the Harvard conference, for example, historian Jarvis Givens questioned whether any widely agreed-upon ethical principles are possible in a nation where many states criminalized teaching and learning in Black communities for decades, resulting in alternate visions of what’s right and just that are sometimes at odds with the priorities of existing school systems. The leadership of the nonprofit American Principles Project, meanwhile, told Education Week that any effort toward a field of educational ethics would need to prioritize parental perspectives and respect conservative moral values in order to gain widespread support.

With public education now such a hot-button political issue, many key stakeholders are also more interested in imposing their own preferred solutions than in seeking consensus. And Superintendent Freeman, Boston Teachers Union President Jessica Tang, and New York City special education student support lead Khalya Hopkins were among the K-12 practitioners at the Harvard conference who raised practical questions around everything from staffing to funding.

Still, Levinson is convinced that an ethical lens can be a powerful tool for educators in the hot seat.

“We need to be honest about the complexity of these decisions,” she said.

The value of studying realistic ethical dilemmas

The most important tools used by educational ethicists are called “normative case studies.”

These short write-ups describe realistic situations in which relatable protagonists must navigate moral gray areas. Trained facilitators then lead discussions designed to help participants consider the situation from every angle. So far, Levinson and her team have developed roughly four dozen such case studies. Many are available online .

One scenario featured at the conference is called “Talking Out of Turn.” It explores the complexities of political speech in schools through the stories of real-life educators including David Roberts, a substitute teacher in California who was banned from subbing at Clovis West High School after wearing a Black Lives Matter pin at school, and Tim Latham, a history and government teacher in Lawrence, Kan., who claimed his contract was not renewed because he’d criticized presidential candidate Barack Obama in class and because he maintained a website containing patriotic and military material.

Inside a Harvard classroom, a mix of college professors and K-12 educators drew easy connections between the details of the case study and their own fraught experiences planning social studies curricula and responding to colleagues who refuse to use students’ chosen pronouns.

Much of their dialogue focused on identifying underlying themes, such as the tensions inherent in protecting rights of teachers who are politically out of step with the communities in which they work.

That’s what educational ethics aims for, Levinson told the conference attendees, saying that educators need to be prepared in advance with an “ethical repertoire” they can lean on in the heat of the moment.

“The same way you might say, ‘This calls for a turn-and-talk, but that calls for a small-group discussion,’ teachers should have a set of ethical options already in mind,” she said.

‘We found ourselves at the center of a maelstrom’

During the fall of 2022, Levinson’s team walked Superintendent Freeman and more than 300 Guilford educators through Talking Out of Turn and another ethical case study during a series of professional development days.

The district’s troubles began with a school-mascot renaming controversy , then intensified with fights over social-emotional learning and a graphic novel in the school library that featured a gay character. Things boiled over when Freeman started referencing the work of such left-leaning antiracist figures as Ibram X. Kendi in his public remarks. Last September, with help from a conservative Idaho-based advocacy group called We the Patriots USA, a group of local parents filed a lawsuit accusing the Guilford district of pushing a “radical racist agenda.”

“Somehow, we found ourselves at the center of a maelstrom,” Freeman said. “I didn’t even know what critical race theory was until I was accused of teaching it.”

Dedicating a day to discussing case studies didn’t solve the Guilford district’s problems. But the superintendent said teachers appreciated the chance to think through options for balancing their sometimes-competing desires to teach social justice-themed material, ensure that conservative students still feel free to speak in class, and avoid being targeted on social media.

“The feedback was, ‘We feel seen and heard today,’” Freeman said.

But while the ethical case study model has promise, K-12 education has been slower than many other fields to integrate the principles and processes employed by professional ethicists.

Khalya Hopkins, the administrator who works with special education teachers in New York City, highlighted some of the day-to-day challenges. The reality is that her district creates many of the ethical dilemmas she and her colleagues must face daily, Hopkins said, citing as an example difficult decisions about whether to compromise one’s personal integrity by signing documents promising services that are unlikely to get delivered effectively.

That’s why the details of any formal push to bring education ethicists into schools matter greatly, Hopkins argued.

“The biggest issue is who’s going to be doing this,” she said. “I don’t want only older white men making decisions or determining what is ethical for poor Black and brown people.”

Establishing a more formal academic field of educational ethics

Though dozens if not hundreds of professors from disciplines as diverse as philosophy and public policy are interested in issues related to educational ethics, Levinson said they currently lack many of the key facets of a formal academic field, such as dedicated tenure lines and journals.

There are, however, recent signs of movement. The Spencer Foundation, a major education-philanthropy, provided financial support for the Harvard conference. (The Spencer Foundation helps support Education Week’s coverage of educational research.) Harvard Graduate School of Education Dean Bridget Terry Long has also thrown her support behind the effort.

Still, given the contemporary political climate, the K-12 sector isn’t exactly flush with faith that even the most well-intentioned outsider can play the role of honest broker in heated debates about issues such as schools’ treatment of transgender students.

“We do what’s right for children,” said Freeman, who described his district as committed to supporting and celebrating trans kids. “That doesn’t mean we have a political agenda.”

“How I see it is that I’m also working to protect kids who identify as transgender from being exploited through expensive medical treatments,” said Terry Schilling, the president of the American Principles Project, who describes the push to recognize non-traditional gender identities as undermining a shared sense of reality and thus “inherently divisive.”

For Levinson and her team, however, such diverging views are precisely why ethicists are needed throughout the K-12 world.

“By 2050, I hope that teachers and professors, school principals and university provosts, PTA presidents, central office administrators, school boards, Head Start directors, charter network CEOs, learning technology providers, after-school partners, and even students think it is totally natural that they can call on education ethicists whenever they face an ethical dilemma or conflict they feel ill-equipped to resolve on their own,” she said.

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Med Ethics

Ethics education to support ethical competence learning in healthcare: an integrative systematic review

Henrik andersson.

1 Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, Linnaeus University, Växjö, Sweden

2 Centre of Interprofessional Collaboration within Emergency Care (CICE), Linnaeus University, Växjö, Sweden

3 Faculty of Caring Science, Work Life, and Social Welfare, University of Borås, 50190 Borås, Sweden

Anders Svensson

4 Department of Ambulance Service, Region Kronoberg, Växjö, Sweden

Catharina Frank

Andreas rantala.

5 Department of Health Sciences, Lund University, Lund, Sweden

6 Emergency Department, Helsingborg General Hospital, Helsingborg, Sweden

Mats Holmberg

7 Centre for Clinical Research Sörmland, Uppsala University, Eskilstuna, Sweden

8 Department of Ambulance Service, Region Sörmland, Katrineholm, Sweden

Anders Bremer

9 Department of Ambulance Service, Region Kalmar County, Kalmar, Sweden

Associated Data

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethical problems in everyday healthcare work emerge for many reasons and constitute threats to ethical values. If these threats are not managed appropriately, there is a risk that the patient may be inflicted with moral harm or injury, while healthcare professionals are at risk of feeling moral distress. Therefore, it is essential to support the learning and development of ethical competencies among healthcare professionals and students. The aim of this study was to explore the available literature regarding ethics education that promotes ethical competence learning for healthcare professionals and students undergoing training in healthcare professions.

In this integrative systematic review, literature was searched within the PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycInfo databases using the search terms ‘health personnel’, ‘students’, ‘ethics’, ‘moral’, ‘simulation’, and ‘teaching’. In total, 40 articles were selected for review. These articles included professionals from various healthcare professions and students who trained in these professions as subjects. The articles described participation in various forms of ethics education. Data were extracted and synthesised using thematic analysis.

The review identified the need for support to make ethical competence learning possible, which in the long run was considered to promote the ability to manage ethical problems. Ethical competence learning was found to be helpful to healthcare professionals and students in drawing attention to ethical problems that they were not previously aware of. Dealing with ethical problems is primarily about reasoning about what is right and in the patient’s best interests, along with making decisions about what needs to be done in a specific situation.

Conclusions

The review identified different designs and course content for ethics education to support ethical competence learning. The findings could be used to develop healthcare professionals’ and students’ readiness and capabilities to recognise as well as to respond appropriately to ethically problematic work situations.

Introduction

Healthcare professionals and students undergoing training in healthcare professions are confronted with a variety of ethical problems in their clinical practice. These ethical problems appear as ethical challenges, conflicts, or dilemmas that influence the daily provision of care and treatment for patients [ 1 , 2 ]. Addressing these problems requires ethical competencies that involve the ethical dimensions of sensitivity, knowledge, reflection, decision making, action, and behaviour [ 3 ]. As the future workforce, students need training to effectively deal with ethically problematic situations [ 4 ], and experienced professionals need to develop ways to manage ethical problems [ 5 ]. Therefore, it is essential for ethics education to support the learning and development of ethical competencies among healthcare professionals and students undergoing training to work in healthcare. In this study, ethics education is referred to educational components with a content of support and learning activities that promote understanding and management of ethical problems. The focus is on ethics education that is carried out at universities and in clinical practice. In conclusion, it would be valuable to first compile the existing knowledge about designs and course content that support ethical competence learning.

The provision of care is based on patients’ care needs and the complexity of their health conditions; this process is further complicated by the nature of the care environment, which is frequently chaotic and/or unpredictable, with care often being provided under stressful working conditions [ 6 – 10 ]. Healthcare professionals and students in clinical practice are confronted daily with difficult choices and must cope with questions of ‘rightness’ or ‘wrongness’ that influence their decision-making and the quality of the care provided [ 11 , 12 ]. The underlying reasons for the emergence of ethical problems in everyday healthcare work are multifaceted, unfold over time, and are caused by factors such as a lack of resources, insufficient leadership, hierarchical organisational structures, chaotic work environments, or a lack of competencies [ 13 ]. Ethical problems and value conflicts are inherent in clinical practice and do not necessarily mean that healthcare professionals or students have done anything inappropriate or that structures are inadequate. Whatever the cause, ethical problems can lead to conflicts between principles, values, and ways of acting [ 14 ]. This, in turn, might lead to compromised moral integrity and generate moral distress [ 11 , 15 , 16 ], as these reactions result from acting or not acting on the basis of one's own sense of right and wrong [ 17 ]. At worst, moral distress can lead to moral injury, which occurs as a result of witnessing human suffering or failing to prevent outcomes that transgress deeply held beliefs [ 18 ]. Therefore, healthcare professionals and students in clinical practice need to develop their ethical competencies to be prepared for their responsibility and commitment to caring for patients.

The concept of competence is multifaceted and include many things. In this study, competence is viewed as entailing knowledge, skills, and attitudes that are essential when healthcare professionals and students are carrying out their work in clinical practice [ 19 ]. Ethical competence contain components such as the capability to identify ethical problems, knowledge about the ethical and moral aspects of care, reflection on one’s own knowledge and actions, and the ability to make wise choices and carefully manage ethically challenging work situations [ 3 ]. Ethical competence is essential for the ability to respect the patient’s rights and the quality of care [ 20 , 21 ]. This means that ethical competence includes not only knowledge of the ethical and moral aspects of care, but it also includes moral aspects of thinking and decision-making. Furthermore, ethical competence is important since it may prevent or reduce moral distress [ 22 ].

Healthcare professionals and students in clinical practice need a solid foundation that supports when they are confronted with ethically problematic situations. Care and treatment depend not only on knowledge and skills or acting according to guidelines; they also depend on personal values, beliefs, and ethical orientations [ 23 ]. There are various strategies to support and develop the capability to identify and solve ethical problems. [ 24 ]. Ethics education is one such way to develop ethical competencies [ 20 ]. Simultaneously, ethics education raises questions about the content and teaching methods relevant for clinical practice [ 25 ]. While theoretical education via small-group discussions, lectures, and seminars in which ethical principles are applied is quite common [ 26 ], an alternative educational method is simulation-based learning [ 27 ]. However, there is no evidence to support the determination of the most effective strategy to promote the application of ethics in care. There are also challenges to teaching and assessing ethics education. For example, ethics education does not always occur contextually or in a realistic situation, and theoretical knowledge of ethics does not necessarily lead to improved ethical practice [ 28 ]. Teaching ethical principles and maintaining codes of ethics without contextualising them risks forcing healthcare professionals and students in clinical practice to adapt to ethical practice without questioning their own beliefs. Thus, ethical competence risks being hampered by limited reflection and moral reasoning about the situation as a whole [ 29 ].

In summary, ethical problems in everyday healthcare work arise for many reasons, and sometimes themselves constitute threats to ethical values. Hence, healthcare professionals and students in clinical practice require readiness and the capability to recognise and respond appropriately to ethically problematic work situations. Therefore, the aim of this integrative review was to explore the available literature on ethics education that promotes ethical competency learning for healthcare professionals and students undergoing training in healthcare professions.

This integrative review followed the method described by Whittemore and Knafl and was used to summarise and synthesise the current state of research on a particular area of interest [ 30 ], which in this study was the area of ethics education in healthcare.

According to Whittemore and Knafl [ 30 ], the review process is composed of the following stages, which were applied in this study:

Stage 1: problem identification

Two questions were addressed in this review to explore the available literature regarding ethics education: (1) How can ethics education support the understanding and management of ethical problems in clinical practice? (2) What kind of design and course content can support ethical competence learning?

Stage 2: literature search

Prior to the literature search, a study protocol was submitted to the PROSPERO database with the ID number CRD42019123055. In collaboration with three experienced information specialists at a university library, guidance and support were provided in the creation of a search strategy. A systematic and comprehensive data search was conducted using the standards of the PRISMA guidelines [ 31 ]. To enhance the breadth and depth of the database searches, the main search strategy was based on three themes; study population, exposure/intervention and outcomes. The following search and/or Medical Subject Heading’s (MeSH) terms were used: ‘health personnel’, ‘students’, ‘ethics’, ‘moral’, ‘simulation’ and ‘teaching’. The search strategy was different between the databases as the construction of search and MeSH terms differs between the selected databases, see Table Table1. 1 . The main search was carried out between 22 and 23 June 2020 in three scientific publication databases and indexing services: PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO. A supplementary search was carried out 10 January 2022.The searches was limited to (a) articles in English, (b) peer-reviewed articles, (c) theoretical articles as well as qualitative and quantitative empirical research articles, and d) articles published in the last 12 years (January 1, 2010–December 31, 2021). Articles were included if published after 2010, and they (a) described the design and content of ethics education for healthcare professionals or students in, or preparing for, clinical practice, and/or (b) described ethics education supportive of understanding and/or managing ethical problems in clinical practice. Articles were excluded if they focused on research ethics, ethical problems in a military context and ethical consultation with the primary and main goal of supporting ethical decision-making for an individual patient and the healthcare team. In the literature search, the search for “grey literature” such as dissertations, conference papers, reports, etc. was excluded since this was too resource and time consuming. The article searches resulted in 5953 articles, including 1559 in PubMed, 529 in CINAHL, and 3865 in PsycINFO. For a detailed description of the search results, see Fig. 1 . After the search process was completed, all the articles were uploaded onto Endnote X9 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA), and duplicates were then excluded (n = 860). A total of 5093 articles were then imported into the Rayyan QCRI, a web-based sorting tool for systematic literature reviews [ 32 ].

Description of the search strategy with three themes and the search results

Flow diagram of the data selection and quality assessment process based on the PRISMA statement

Four of the authors (HA, AB, AS, and MH) independently screened all titles and abstracts, with the support of Rayyan QCRI, against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The screening process consisted of two steps: (1) screening of articles identified in the main search and (2) screening of articles identified in the supplementary search. In the screening of articles identified in the main search, the blinded article selection in Rayyan QCRI indicated a 93% consensus between the authors with respect to the articles to exclude (n = 3811). After this, those articles for which there was no consensus regarding their inclusion (n = 287) were screened. Through discussions between the authors (HA, AB, AS, and MH), consensus was reached on which articles should then be excluded (n = 235). In the screening of articles identified in the supplementary search, the blinded article selection in Rayyan QCRI indicated a 95% consensus between the authors with respect to the articles to exclude (n = 953). After this, those articles for which there was no consensus regarding their inclusion (n = 42) were screened. Through discussions between the authors (HA, AB, AS, and MH), consensus was reached on which articles should then be excluded (n = 33). In total, 61 articles were selected for an additional full-text review. The articles were independently read in full by five of the authors (HA, AB, AS, MH, and AR) and then discussed, leading to an agreement to exclude 21 articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria. This led to 40 articles remaining for the quality assessment (see Fig. 1 ).

Stage 3: data evaluation

The quality assessment of the 40 articles was independently performed by two of the authors (HA and AB). A critical appraisal tool was used to score the articles on a four-graded scale (i.e., good, fair, poor, and very poor) [ 33 ]. The quality assessment consisted of two steps: (1) quality assessment of articles identified in the main search and (2) quality assessment of articles identified in the supplementary search. In the quality assessment of articles identified in the main search, there was consensus on the quality of 17 of the reviewed articles. However, there were different views on the quality assessment of 14 articles. Any discrepancies regarding authenticity, methodological quality, information value, and representativeness were considered, discussed, and resolved in the data evaluation process [ 34 ], leading to consensus between the authors regarding 11 articles pending between two adjacent grades: good–fair (n = 6), fair–poor (n = 3), and poor–very poor (n = 2). The authors’ quality assessment differed by more than one grade regarding three articles. However, even in these cases, the disagreement could be resolved through discussions between the two authors, after which a consensus was reached. In the quality assessment of articles identified in the supplementary search, there was consensus on the quality of 7 of the reviewed articles. However, there were different views on the quality assessment of 2 articles. Any discrepancies regarding authenticity, methodological quality, information value, and representativeness were considered, discussed, and resolved in the data evaluation process [ 34 ], leading to consensus between the authors regarding 2 articles pending between two adjacent grades good–fair. No articles were excluded due to a low-quality score. The characteristics of the included articles, as well as the quality scores, are presented in Table Table2 2 .

Characteristics of the included articles

Stage 4: data analysis

The data analysis was conducted by the first author. The findings were summarised and synthesised using a thematic analysis method [ 35 ] to identify the key themes that describe ethics education for healthcare professionals and students in clinical practice. This inductive approach also allowed us to answer the question regarding the design and content of ethics education and how ethics education could support the understanding and/or management of ethical problems in clinical practice, based on the available literature.

The analysis was conducted in the following six phases [ 35 ]: (1) reading and re-reading the included articles closely to become familiar with the data, (2) generating initial codes (228 codes in the present study) based on the information obtained from the included articles, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing a report where the findings are presented in terms of broad themes. The interpretation of the themes was discussed, and disagreement was resolved through discussion between the authors (HA, CF, AB, and AR) until a common understanding was reached.

Forty articles were included for review to explore the available literature regarding ethics education for healthcare professionals and students in clinical practice. The results showed a widespread international distribution of studies. Most of the studies were conducted in the United States (n = 5) and Taiwan (n = 5). When dividing the articles into continents, 17 were from Asia, 14 from Europe, six from North America, and three from Australia. Table Table3 3 shows the key themes and sub-themes identified through the thematic analysis.

Sub-themes and key themes identified in the review

Making ethical competence learning possible

Making ethical competence learning possible for managing ethical problems in clinical practice requires support. However, this support entails those certain conditions be met for learning in the organisation in which ethics education is conducted, including opportunities to plan the education. The design and content of education are governed by external structures and the way in which the learning objectives have been specified. To support learning, it is also important that education is designed to facilitate opportunities to receive and create meaning with respect to the information received, change one’s own values and attitudes, and determine the consequences of one’s own actions. Interaction with others is important since it can constitute a valuable source of knowledge, especially with respect to determining whether the individual healthcare professional or student has understood or done something correctly. Simultaneously, ethics education is influenced by both the healthcare professionals and the students who have different qualifications, expectations, and strategies for their learning.

The factors influencing the planning and organization of ethical education were discussed in 32 articles. Three sub-themes were identified: (1) creating conditions for learning, (2) designing strategies for learning, and (3) interacting with others.

Creating conditions for learning

A starting point for making ethical competence learning possible is to identify and shed light on the kinds of ethical problems that healthcare professionals and students in clinical practice are expected to be able to manage and to create conditions for this learning. Therefore, it is important that ethics education reflect the relevant conditions for ethical competence learning by using real work situations [ 36 ]. One way to create such conditions is to construct appropriate learning objectives that clearly describe what should be achieved in terms of knowledge, skills, approaches, and values to effectively manage ethical problems [ 37 , 38 ]. However, the perception of what is relevant is influenced by healthcare professionals’ and students’ previous experiences of ethical problems in their everyday healthcare work. Limited experience entails a risk that the education will not be perceived as relevant, and that the educational content may be difficult to absorb [ 39 ].

Another condition that influences ethics education is the time available. Developing an ethical identity and creating meaning in discussions about ethical problems in everyday healthcare work takes time [ 37 , 40 ]. Simultaneously, it might be difficult to predict how long, for example, group discussions may take to shed light on the various aspects of ethical problems [ 39 ]. There is thus a risk that the time will be too short and insufficient to finish the discussion, or that there may be too much time, thus causing the discussions to be perceived as less engaged [ 37 ]. Therefore, it is important that the time aspect be considered in the design of education.

Finally, it is essential to create conditions for psychological safety and confidence in ethics education, or, in other words, to enable opportunities to express opinions or make blunders without this leading to consequences for the participants [ 41 ]. Instead, trust between the participants should be emphasised and acknowledged in discussions about ethical problems in clinical practice [ 40 , 42 , 43 ]. Simultaneously, there is a risk that high staff turnover and frequent changes in management may limit opportunities for building trust through conversation [ 44 ]. Passive or absent healthcare professionals and students might also limit opportunities for establishing such trust, for example, in group discussions [ 45 ].

Design strategies for learning

Different design strategies make ethical competence learning possible, through which the healthcare professionals and students can be brought to ask questions, make comments, and talk about their previous knowledge or own experiences. Knowledge of, for example, ethical values can be gained through theoretical lectures and the reading of appropriate literature [ 46 – 48 ]. Simultaneously, it is valuable to design ethics education so that theoretical learning activities are integrated with practical ones and thereby provide an experience of real-life situations [ 46 ]. Skills can be practiced through workshops [ 49 ], case studies and problem-solving sessions [ 37 , 43 , 47 , 48 , 50 – 53 ]. Understanding one’s own values and attitudes can be facilitated through, for example, role-play or simulation activities [ 54 – 56 ], narratives [ 40 , 57 , 58 ], storytelling [ 42 ] and discussions in small groups [ 38 , 43 – 45 , 47 , 59 – 62 ]. Small group discussions are appropriate when healthcare professionals or students are unwilling to stand out by asking questions or giving individual opinions in learning situations in which many people participate [ 63 ].

There are also different educational technologies to consider in the design of strategies for ethical competence learning. For example, the internet makes it easier to deliver lectures and carry out exercises [ 64 ], as well as to discuss issues in groups with digital aids [ 59 ]. This means that ethics education can take place in the form of internet-based education where video conferencing technique is used. This technique is valuable when using external educators in a rural setting for example in rural-based hospitals [ 59 ]. This technique is also useful to stimulate discussions with other healthcare professionals or students who are outside their regular workplaces [ 59 ]. However, a prerequisite for internet-based education is that the workplace has the required learning resources such as reliable internet connection and video equipment [ 64 ].

Ethics education needs to be built on strategies that optimise the ability to achieve the desired learning objectives [ 48 ]. To achieve these objectives, it may be necessary to choose different design strategies [ 36 ]. However, the strategy that best supports the development of a “professional self” is difficult to determine, for example, in terms of its ability to influence healthcare professionals’ and students’ capabilities for moral sensitivity [ 47 , 65 , 66 ] and critical thinking [ 47 ]. Nevertheless, support and learning activities do not necessarily promote ethical competence learning. Instead, these activities can also lead to stagnation in the development of ethical competence [ 67 , 68 ].

Interacting with others

An open atmosphere and interaction between participants are important in ethics education when sensitive issues are discussed [ 69 ]. Sometimes, it is difficult to express one’s critical thoughts about ethical problems in everyday healthcare work, since relationships with others and cohesion between individuals can be affected and compromised [ 45 , 57 ]. Simultaneously, there is a need for healthcare professionals and students to formulate their thoughts, feelings, and intentions about the ethical problems that they have observed themselves or heard about through colleagues [ 37 , 38 , 41 , 43 , 45 ]. Making ethical competence learning possible based on problem solving, interaction, and discussion of ethical problems in clinical practice can therefore be a support mechanism for healthcare professionals and students [ 37 ]. Learning together about issues that are perceived as ethically problematic can strengthen both the individual and their relationships with their colleagues [ 44 , 52 ].

Simulation is a way of highlighting ethical problems that exist in interactions with other individuals, such as patients or family members [ 54 ]. Narrative groupwork is another way of highlighting and processing ethical problems [ 57 ]. Through a narrative, different perspectives can be made visible and lead to in-depth learning about ethically challenging work situations [ 58 ]. With group discussions, ethical problems can be viewed in different ways [ 59 ], which in turn can lead to improvements in dealing with such problems [ 44 ]. However, if group discussions are to lead to improvements, it is necessary that there be a willingness to discuss what is perceived as ethically problematic in everyday healthcare work [ 38 , 45 ], as well as an interest in learning new approaches [ 37 ]. There is also a need for a welcoming climate in which the contradictions between different perceptions and attitudes can be balanced in a constructive way [ 43 , 51 ].

Having awareness of one’s own thoughts and perceptions

Ethical competence learning can help healthcare professionals and students in clinical practice direct their attention to ethical problems that they were not previously aware of. Such learning can involve unconscious attitudes, approaches, or emotions. These aspects influence how healthcare professionals and students react to ethical problems in everyday healthcare work.

The aspects that influence awareness of one’s own thoughts and perceptions were discussed in 22 articles in terms of both educational design and the content of ethics education. Two sub-themes were identified: (1) visualising attitudes and approaches, and (2) experiencing emotional conditions.

Visualising attitudes and approaches

Being aware of one’s own thoughts and perceptions in one’s attitudes and approaches to circumstances such as a certain illness, patient, or event influence what is perceived as an ethical problem in clinical practice [ 41 , 70 ]. One way of designing ethics education that facilitates the visualisation of ethical problems is to use a narrative approach [ 40 , 57 , 58 ]. Using narrative writing, one’s own or others’ attitudes and approaches to everyday healthcare work situations where ethical problems occur can be made visible [ 57 ]. Examples of such ethical problems are when honesty and respect for the patient are not demonstrated, or when the establishment of trust in the care encounter is lacking [ 57 ].

Another way to visualise one’s own or others’ attitudes and approaches when designing ethics education is to use learning activities based on problems or scenarios [ 48 , 51 , 52 , 54 – 56 , 64 ]. This ethical competence learning focuses on challenging and realistic situations, such as conflicts regarding informed consent or cases where tensions arise between the patient’s wishes and needs in relation to professional norms [ 36 ]. Problem- or scenario-based learning stimulates healthcare professionals and students to learn and develop new understandings that allow them to manage ethical problems in their clinical practice [ 36 ]. Such learning could also create a means of engagement to discuss how ethical problems should be managed [ 64 ]. The visibility can also emerge by reserving time for ethical reflection and, in systematic forms, discussing ethical problems in everyday healthcare work [ 38 , 43 – 45 , 59 , 70 ]. Attitudes towards a particular illness or patient, for example, govern our way of justifying the approaches used [ 70 ]. By highlighting how healthcare professionals and students think about and analyse their attitudes and approaches when designing ethics education, previous habits can be made visible and critically examined [ 44 ]. The visibility of attitudes and approaches promotes a process of change in one’s own thoughts and perceptions [ 43 , 45 ]. However, it is essential to consider that attitudes and approaches are complex, developed over time, and strongly influenced by the perceptions of individuals who are close to the healthcare professionals and students undergoing training in healthcare professions [ 36 , 48 ]. Accordingly, ethics education to support ethical competence learning does not always lead to a change in how ethical problems are managed in everyday clinical practice [ 71 ].

Experiencing emotional conditions

Awareness of one’s own or others’ emotions influences what is perceived as an ethical problem in everyday healthcare work. Healthcare professionals and students in clinical practice encounter a variety of ethical problems in which they are either actors or observers. Depending on the prevailing circumstances on site and at a given time, ethical problems, and their significance, as well as their relevance, can be experienced differently. When designing ethics education, real experiences, such as incidents that are ethically challenging and witnessed by healthcare professionals or students, can be used in ethical competence learning [ 58 ]. Group discussions make it possible for all participants to hear different interpretations and reflections on the same situation [ 38 , 45 ]. Furthermore, such discussions can draw attention to situations where care and treatment have been experienced as unethical, such as when the patients’ concerns are not heard, or their needs are not met [ 61 ].

By imitating a realistic situation through simulation, healthcare professionals and students are given the opportunity to learn about real-life situations, apply ethical content in the situation, and experience different emotional states [ 56 ]. Educational content that highlights emotions, such as feelings of dependence, vulnerability, fear of abandonment, and a lack of control, gives healthcare professionals and students an opportunity to change their perspectives on factors such as caregiving and care-recipients [ 55 ]. Simulation can also be a way to raise awareness of other people’s ways of feeling and experiencing specific work situations, regardless of whether they play the role of professional, patient, or family member [ 56 ].

Doing right by the patient’s best interests

Healthcare professionals and students in clinical practice are constantly faced with ethical problems related to patients, their significant others, colleagues, and the work organization. Dealing with such problems primarily involves reasoning about what is right and good to make decisions about what needs to be done in a specific situation. However, doing right based on the patient’s best interests can sometimes jeopardize the management of ethical problems since it could conflict with other patients’ interest, which may not be ethically acceptable or legally permitted.

Those aspects influencing healthcare professionals’ and students’ capabilities to do right by the patient’s best interests were discussed in 19 articles. Two sub-themes were identified: (1) managing emotions and tensions, and (2) managing different perspectives in the situation.

Managing emotions and tensions

Ethical problems can provoke strong emotions, such as anger, disapproval, and frustration [ 40 ]. These emotions, in turn, generate tensions, such as those between ethical values and legal principles in relation to how healthcare professionals and students in clinical practice perceive a particular situation [ 40 , 51 ]. Therefore, it is essential that ethics education be designed to provide time and space for reflection. By reflecting together with others, thoughts and perceptions about these emotions and tensions can be verbalised [ 43 , 72 ]. Ethics education should provide the opportunity to learn how to deal with emotions [ 40 ] and foster understanding of what is ethically ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ for the patient [ 45 ], which in turn influences the decisions made by healthcare professionals and students in clinical practice [ 51 , 70 ]. Group discussion, for example in ethics seminar, is a way to reduce unethical behaviour [ 73 ]. There is, however, a difference between learning how to manage ethical problems in everyday healthcare work and how these problems are actually managed, since one’s own inabilities or limitations may influence the outcome [ 62 ].

Managing different perspectives on the situation

In everyday healthcare work, healthcare professionals and students face several challenges in determining how to ‘do the right thing’ in situations that arise in their contact with patients and their significant others. Ethical problems can arise when two perspectives, such as an ethical and a legal perspective, collide, as would be the case when there is conflict between what is perceived to be best for the patient and the patient’s right to self-determination [ 37 ]. There may also be a feeling of inadequacy in managing ethical problems in care situations [ 38 ] since there is rarely only one way to cope with the situation [ 51 ]. Therefore, ethics education needs to be designed in such a way that the content includes both medical and ethical reasoning when the care situation is to be resolved [ 70 , 74 ].

The design of such training could consist of lectures that are combined with watching movies, playing games, and performing case analyses and group discussions [ 37 , 47 , 60 , 65 ]. Through such training, an increased understanding of ethical problems can be gained [ 54 , 72 ], for example, regarding the ways in which certain patients, events, and situations are to be viewed [ 37 , 57 , 65 ]. Ethical competence learning with a focus on ‘thinking ethics’ and problematising one’s own capabilities to judge and act can be an eye-opener for healthcare professionals and students [ 72 , 75 ]. This can strengthen the capability to identify certain situations and provide examples of instances where ethical values and norms have been violated [ 66 ].

Even if the design and content of ethics education focus on thinking about critical ethics, this does not necessarily mean that the degree of critical ethics thinking is influenced [ 47 ]. Prerequisites for ethical competence learning of how to manage different perspectives and do right by the patient’s best interests are, among other things, that there is time for discussion, and that the educational content is perceived as useful [ 37 ]. It is also crucial that such learning be based on consideration and respect for different beliefs, so that ethical problems can be managed effectively in everyday healthcare work [ 43 – 45 , 54 ].

Making ethical competence learning possible, having awareness of one’s own thoughts and perceptions, and doing right by the patient’s best interests are important aspects when seeking to increase the understanding and management of ethical problems in everyday healthcare work.

An important aspect emphasised in the present study is the need to create a psychosocial climate that allows healthcare professionals and students to feel safe. Previous knowledge reveals that feeling psychologically safe is important for engagement in educational activities, regardless of the context in which they are implemented [ 76 ]. Hence, it is important that educators use an approach that clarifies what psychological security in feedback conversations can look like [ 77 ]. To promote effective learning conditions in which healthcare professionals and students feel safe, educators need to encourage an open dialogue aimed at enhancing the implementation of the intended learning activity [ 76 , 77 ].

The results present different designs and educational strategies for making ethical competence learning possible. In general, it is essential that educators develop course content that supports healthcare professionals and students in developing ethical competence in terms of their ethical decision-making ability and the moral courage to confront ethical dilemmas [ 78 ]. However, although ethical education might increase ethical sensitivity and the ability to detect an ethical problem, it is not obvious that education influences the development of ethical behaviour [ 79 ].

The results show how interaction with others is important since it constitutes a valuable source of knowledge; it also allows for the determination of whether the individual healthcare professional or student has understood or done something in an ethically defensible manner. Relationships between people constitute the foundation of ethics, and ethics is essential to the maintenance of relationships between two or more people [ 80 ].

Another critical aspect is the value of clinical experience. According to the results, limited experience poses a potential risk of not enabling healthcare professionals and students to absorb and contextually relate to the content of ethical education. However, previous research indicates that those with less clinical experience are more perceptive of ethical issues than more experienced colleagues, possibly counteracting the potential lack of experience [ 11 ].

The results underline the significance of attending to ethical problems that individual participants in ethics education may not already be aware of. This might be related to the fact that the patients, healthcare professionals, and students each have different and unique perspectives in caring encounters. To provide care based on the preferences of a specific patient, one needs insight into the patient’s lifeworld [ 81 ]. This might pose some challenges in designing and developing course content for ethics education.

Further, based on the present results, narrative approaches and realistic simulation are considered components that could influence ethical competence learning. Such learning should be based on the patient’s perspective to transform healthcare professionals’ and students’ tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge with support from reflective practice [ 82 ]. According to this, reflection with some theoretical depth grounded in caring science can contribute to a deeper understanding beyond that which is common in the clinical practice [ 83 ]. However, being aware of ethical problems—earlier not being aware of—raises new moral concerns among healthcare professionals and students. Thus, ethical education needs to be dynamically designed to capture different aspects of ethical problems.

The result highlights the importance of doing right by the patient’s best interests. Besides clinical competence, decisions regarding care and treatment also require ethical competence [ 3 ]. To do the right and good thing, an educational design that emphasises the healthcare professionals’ and students’ personal experiences, understanding, and views is required; such a skill can be cultivated, for example, through reflection [ 84 ]. Approaches such as moral case deliberation, ethics rounds, or discussion groups can be advantageously used to support ethical reflection [ 85 ]. At the same time, there are challenges regarding how ethical problems can be handled in clinical practice. Each problem and situation is unique, complex, and uncertain, since it can never be completely predicted. Therefore, doing right by the patient’s best interests may not necessarily only be about what to do in a specific situation; it can also be about scrutinising, interpreting, and processing other healthcare professionals’ and students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes to ethical problems in clinical practice.

Doing right by the patient’s best interests also requires an educational design that provides space and time for reflection. Research indicates that the opportunity to share thoughts and obtain support from others, as well as from the organization, when ethical problems occur is considered helpful [ 86 ]. However, there are other factors that are essential for reflection. Space for reflection, for example, to create psychological safety is crucial for healthcare professionals and students to express themselves or make blunders without this leading to consequences. A hierarchical organizational climate influences sensitivity to ethical concerns, and a conformist work attitude could lead to an unwillingness to challenge routines in everyday clinical practice [ 86 ]. Time is also required to ensure that there is an opportunity for reflection. Without time, there is a risk that decision-making regarding ethical problems may become inconsistent [ 87 ].

Methodological strengths and limitations

This study followed the recommendations for conducting and reporting the results of an integrative systematic review, and the researchers have strived to make the research process as transparent as possible, which is considered to have strengthened its reliability.

In this study, a broad literature search strategy was used to find as many articles as possible to answer the study aim and research questions. However, some issues may be encountered when conducting broad literature searches. One is that such a literature search likely leads to a greater number of irrelevant articles that match the search criteria. Another weakness is that it is time consuming to review a great number of articles. Accordingly, there is a risk that relevant articles may have been accidentally deleted, thereby weakening the validity of the study. However, this risk was partly managed by involving four of the authors in the screening process against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The decision not to include “grey literature” can be considered a limitation as this may have affected the validity of the results.

Three available databases at a university in western Sweden were used. Since universities have different levels of licenses to access the contents of the databases, there is a risk that the search terms and search strings used in this study have failed to identify all articles on ethics education due to limited license agreements. Thus, there is a risk that some articles that are available in more extensive license agreements are not included in this literature review, which should be considered a limitation.

The decision not to include the perspective of those who supervise, and mediate ethics education could be seen as a weakness. However, it was a deliberate choice not to include the search term ‘educators’ based on the study aim and research questions. The requirements for educators can be different depending on whether the participants are students at a university or if they are healthcare professionals and are taught at their workplace. However, continued research on what competencies these educators should have in relation to supporting the learning and development of ethical competencies is important, and possibly points to a need for a systematic literature review that describes the educators’ competencies.

This study is limited to and focused on providing answers to questions regarding ethics education in various healthcare contexts in different countries. This is considered, on the one hand, to strengthen the validity and transferability of the results and, on the other hand, to limit the transferability of the results to contexts with similar cultural, economic, and social conditions, which are reflected in the included articles.

This integrative systematic review provides insights into ethics education for healthcare professionals, students, and educators. The results show that ethical competence learning is essential when seeking to draw attention to and deal effectively with ethical problems. Healthcare professionals and students in clinical practice need a supportive learning environment in which they can experience a permissive climate for reflection on ethical challenges, conflicts, or dilemmas that influence everyday healthcare work. The design and course content of ethics education meant to increase the understanding and management of ethical problems in clinical practice may vary. However, regardless of the design or course content, educators need supportive conditions both on campus and in clinical practice to maximise opportunities to generate a high level of learning in ethics education.

Further studies on ethics education should be carried out. Comparative research, through which different educational designs can illuminate what provides the best possible learning process for managing ethical problems, would be valuable. Intervention studies aiming to maintain and protect the autonomy of patients with impaired decision-making capabilities may also be warranted. Another interesting area for further studies is about the educators’ and their competencies in ethics education with a special focus on the requirements if the participants are students at a university or if they are healthcare personnel and are taught at their workplace. Further studies could be used to develop healthcare professionals’ and students’ readiness and capabilities to recognise and respond appropriately when they encounter ethically problematic situations. This would, in turn, give healthcare professionals and students a sense of self-confidence and faith in their everyday clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the librarians Anna Wolke, Ida Henriksson, and Lynn Rudholm at Linnaeus University for their valuable assistance with the systematic literature search process.

Authors' contributions

All the authors contributed to the study design. The review design and literature search were performed by HA and AB. Data extraction was done by HA, AB, AS, MH, and AR. The data analysis was conducted by HA, CF, AB, and AR. All authors made substantial contributions to the study and have read and approved the final version of the submitted manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Open access funding provided by University of Boras. The authors received the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was funded by the Kamprad Family Foundation for Entrepreneurship, Research & Charity (Ref. No. 20180157).

Availability of data and materials

Declarations.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The Right Has an Opportunity to Rethink Education in America

T he casual observer can be forgiven if it looks like both the left and the right are doing their best to lose the debate over the future of American education.

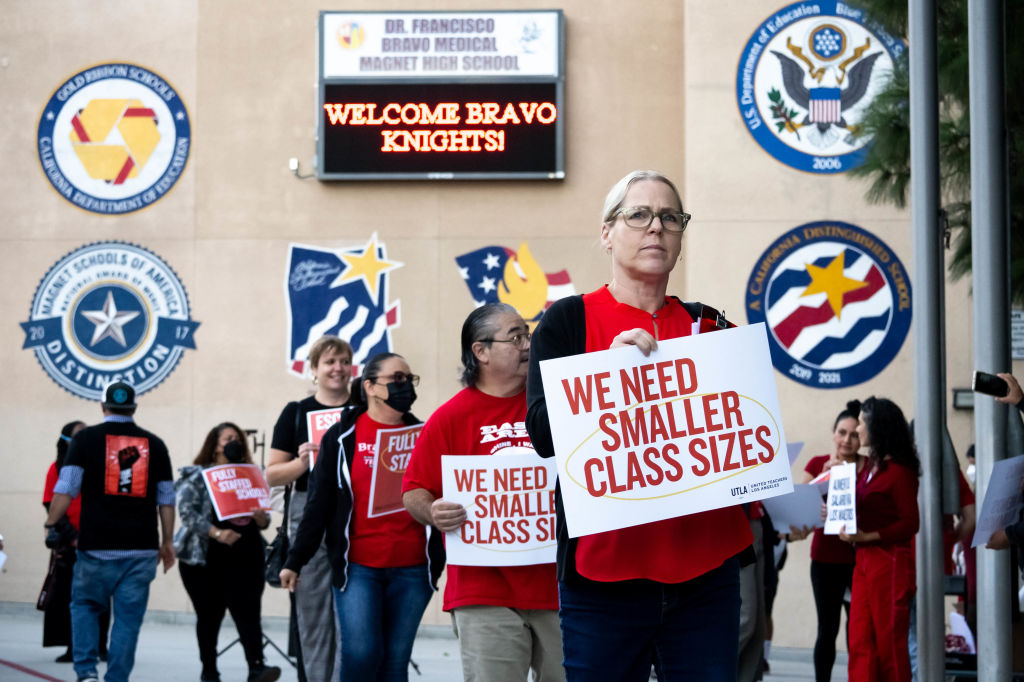

On the left, public officials and self-righteous advocates practically fall over themselves working to subsidize and supersize bloated bureaucracies, hollowed-out urban school systems, and campus craziness. They’ve mutely watched teacher strikes shutter schools and insisted that “true history” requires the U.S. to be depicted as a cesspool of racism and villainy .

Meanwhile, on the right, bleating outrage impresarios have done their best to undercut the easy-to-make case for educational choice by weaving it into angry tirades against well-liked local schools. They’ve taken Taylor Swift, a strait-laced pop star beloved by middle school and high school girls, and imagined her as part of some bizarre Biden Administration PSYOP. Heck, they’ve even decided to try to “ take down ” Martin Luther King, Jr., a Civil Rights icon honored for his legacy of justice, equality, and nonviolence.

What gives?

The left has a problem. Democrats have long benefited from alliances with teacher unions, campus radicals, and the bureaucrats who run the college cartel. This played well with a public that tended to like its teachers, schools, and colleges. But pandemic school closures , plunging trust in colleges , and open antisemitism have upended the status quo.

This has created an extraordinary opportunity for the right—free of ties with unions, public bureaucracies, and academe—to defend shared values, empower students and families, and rethink outdated arrangements. The right is uniquely positioned to lead on education because it’s not hindered by the left’s entanglements, and is thus much freer to rethink the way that early childhood, K-12, and higher education are organized and delivered.

The right also needs to demonstrate that it cares as much (or more) about the kitchen table issues that affect American families as the culture war issues that animate social media. Affordability, access, rigor, convenience, appropriateness, are the things that parents care about, and the right needs something to offer them.

The question is whether the right will choose to meet the moment at a time when too many public officials seem more interested in social media exposure than solving problems.

We’re optimists. We think the right can rise to the challenge.

It starts with a commitment to principle, shared values, and real world solutions. This is easier than it sounds. After all, the public sides with conservatives on hot-button disputes around race, gender, and American history by lopsided margins. Americans broadly agree that students should learn both the good and bad about American history, reject race-based college admissions, believe that student-athletes should play on teams that match their biological sex, and don’t think teachers should be discussing gender in K–3 classrooms.

And, while some thoughtful conservatives recoil from accusations of wading into “culture wars,” it’s vital for to talk forthrightly about shared values. Wall Street Journal-NORC polling , for instance, reports that, when asked to identify values important to them, 94 percent of Americans identified hard work, 90 percent said tolerance for others, 80 percent said community involvement, 73 percent said patriotism, 65 percent said belief in God, and 65 percent said having children. Schools should valorize hard work, teach tolerance, connect students to their community, promote patriotism, and be open minded towards faith and family.

At the same time, of course, educational outcomes matter mightily, for students and the nation . A commitment to rigor, excellence, and merit is a value that conservatives should unabashedly champion. And talk about an easy sell! More than 80 percent of Americans say standardized tests like the SAT should matter for college admissions . Meanwhile, California’s Democratic officials recently approved new math standards that would end advanced math in elementary and middle school and Oregon’s have abolished the requirement that high school graduates be literate and numerate. The right should both point out the absurdity of such policies and carry the banner for high expectations, advanced instruction, gifted programs, and the importance of earned success.

When it comes to kitchen table issues, conservatives can do much more to support parents. That means putting an end to chaotic classrooms. It means using the tax code to provide more financial assistance. It means making it easier and more appealing for employers to offer on-site daycare facilities. It means creating flexible-use spending accounts for both early childhood and K–12 students to support a wide range of educational options. It means pushing colleges to cut bloat and find ways to offer less costly credentials. This means offering meaningful career and technical options so that a college degree feels like a choice rather than a requirement, making it easier for new postsecondary options to emerge, and requiring colleges to have skin in the game when students take out loans (putting the schools on the hook if their students aren’t repaying taxpayers).

Then there’s the need to address the right’s frosty relationship with educators. It’s remarkable, if you think about it, that conservatives—who energetically support cops and have a natural antipathy for bureaucrats and red tape—have so much trouble connecting with teachers. Like police, teachers are well-liked local public servants frustrated by bureaucracy and paperwork. It should be easy to embrace discipline policies that keep teachers safe and classrooms manageable, downsize bloated bureaucracy and shift those dollars into classrooms, and tend to parental responsibilities as well as parental rights.

There’s an enormous opportunity for the right to lead on education today. The question is whether we’re ready to rise to the challenge.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

Product Overview

- Donor Database Use a CRM built for nonprofits.

- Marketing & Engagement Reach out and grow your donor network.

- Online Giving Enable donors to give from anywhere.

- Reporting & Analytics Easily generate accurate reports.

- Volunteer Management Volunteer experiences that inspire.

- Bloomerang Payments Process payments seamlessly.

- Mobile App Get things done while on the go.

- Data Management Gather and update donor insights.

- Integrations

- Professional Services & Support

- API Documentation

Learn & Connect

- Articles Read the latest from our community of fundraising professionals.

- Guides & Templates Download free guides and templates.

- Webinars & Events Watch informational webinars and attend industry events.