- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- March Madness

- AP Top 25 Poll

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

How common is transgender treatment regret, detransitioning?

FILE - South Dakota Republican Rep. Jon Hansen speaks during a news conference at the state Capitol, Tuesday, Jan. 17, 2023, in Pierre, S.D. Hansen is pushing a bill to outlaw gender-affirming health care for transgender youth. (AP Photo/Stephen Groves, File)

FILE - People gather in support of transgender youth during a rally at the Utah State Capitol Tuesday, Jan. 24, 2023, in Salt Lake City. Utah lawmakers on Friday, Jan. 27, 2023, gave final approval for a measure that would ban most transgender youth from receiving gender-affirming health care like surgery or puberty blockers. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer, File)

- Copy Link copied

Many states have enacted or contemplated limits or outright bans on transgender medical treatment, with conservative U.S. lawmakers saying they are worried about young people later regretting irreversible body-altering treatment.

But just how common is regret? And how many youth change their appearances with hormones or surgery only to later change their minds and detransition?

Here’s a look at some of the issues involved.

WHAT IS TRANSGENDER MEDICAL TREATMENT?

Guidelines call for thorough psychological assessments to confirm gender dysphoria — distress over gender identity that doesn’t match a person’s assigned sex — before starting any treatment.

That treatment typically begins with puberty-blocking medication to temporarily pause sexual development. The idea is to give youngsters time to mature enough mentally and emotionally to make informed decisions about whether to pursue permanent treatment. Puberty blockers may be used for years and can increase risks for bone density loss, but that reverses when the drugs are stopped.

Sex hormones — estrogen or testosterone — are offered next. Dutch research suggests that most gender-questioning youth on puberty blockers eventually choose to use these medications, which can produce permanent physical changes. So does transgender surgery, including breast removal or augmentation, which sometimes is offered during the mid-teen years but more typically not until age 18 or later.

Reports from doctors and individual U.S. clinics indicate that the number of youth seeking any kind of transgender medical care has increased in recent years.

HOW OFTEN DO TRANSGENDER PEOPLE REGRET TRANSITIONING?

In updated treatment guidelines issued last year, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health said evidence of later regret is scant, but that patients should be told about the possibility during psychological counseling.

Dutch research from several years ago found no evidence of regret in transgender adults who had comprehensive psychological evaluations in childhood before undergoing puberty blockers and hormone treatment.

Some studies suggest that rates of regret have declined over the years as patient selection and treatment methods have improved. In a review of 27 studies involving almost 8,000 teens and adults who had transgender surgeries, mostly in Europe, the U.S and Canada, 1% on average expressed regret. For some, regret was temporary, but a small number went on to have detransitioning or reversal surgeries, the 2021 review said.

Research suggests that comprehensive psychological counseling before starting treatment, along with family support, can reduce chances for regret and detransitioning.

WHAT IS DETRANSITIONING?

Detransitioning means stopping or reversing gender transition, which can include medical treatment or changes in appearance, or both.

Detransitioning does not always include regret. The updated transgender treatment guidelines note that some teens who detransition “do not regret initiating treatment” because they felt it helped them better understand their gender-related care needs.

Research and reports from individual doctors and clinics suggest that detransitioning is rare. The few studies that exist have too many limitations or weaknesses to draw firm conclusions, said Dr. Michael Irwig, director of transgender medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

He said it’s difficult to quantify because patients who detransition often see new doctors, not the physicians who prescribed the hormones or performed the surgeries. Some patients may simply stop taking hormones.

“My own personal experience is that it is quite uncommon,” Irwig said. “I’ve taken care of over 350 gender-diverse patients and probably fewer than five have told me that they decided to detransition or changed their minds.”

Recent increases in the number of people seeking transgender medical treatment could lead to more people detransitioning, Irwig noted in a commentary last year in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. That’s partly because of a shortage of mental health specialists, meaning gender-questioning people may not receive adequate counseling, he said.

Dr. Oscar Manrique, a plastic surgeon at the University of Rochester Medical Center, has operated on hundreds of transgender people, most of them adults. He said he’s never had a patient return seeking to detransition.

Some may not be satisfied with their new appearance, but that doesn’t mean they regret the transition, he said. Most, he said, “are very happy with the outcomes surgically and socially.”

Follow AP Medical Writer Lindsey Tanner at @LindseyTanner.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

UK Edition Change

- UK Politics

- News Videos

- Paris 2024 Olympics

- Rugby Union

- Sport Videos

- John Rentoul

- Mary Dejevsky

- Andrew Grice

- Sean O’Grady

- Photography

- Theatre & Dance

- Culture Videos

- Food & Drink

- Health & Families

- Royal Family

- Electric Vehicles

- Lifestyle Videos

- UK Hotel Reviews

- News & Advice

- Simon Calder

- Australia & New Zealand

- South America

- C. America & Caribbean

- Middle East

- Politics Explained

- News Analysis

- Today’s Edition

- Home & Garden

- Fashion & Beauty

- Travel & Outdoors

- Sports & Fitness

- Sustainable Living

- Climate Videos

- Behind The Headlines

- On The Ground

- Decomplicated

- You Ask The Questions

- Binge Watch

- Travel Smart

- Watch on your TV

- Crosswords & Puzzles

- Most Commented

- Newsletters

- Ask Me Anything

- Virtual Events

- Betting Sites

- Online Casinos

- Wine Offers

Thank you for registering

Please refresh the page or navigate to another page on the site to be automatically logged in Please refresh your browser to be logged in

Gender reversal surgery is more in-demand than ever before

But what are the consequences, article bookmarked.

Find your bookmarks in your Independent Premium section, under my profile

Stay ahead of the trend in fashion and beyond with our free weekly Lifestyle Edit newsletter

Thanks for signing up to the lifestyle edit email.

Gender reassignment surgery has been available on the NHS for more than 17 years.

It’s a treatment for those experiencing gender dysphoria, whereby a person recognises a discrepancy between their biological sex and their gender identity.

Gender identity clinics are in place throughout the UK to provide support to those feeling distressed by the condition - but what happens when a trans person undergoes surgery and later decides to revert back to their original gender?

- John Lewis gender neutral clothing labels faces public backlash

Is it possible? Is it safe? And is it available on the NHS?

These are not questions that are not easily-answered. Five phone calls and endless emails later, the details regarding what circumstances would allow for such a treatment to be carried out on the NHS remain muddled.

It's potentially why some of those seeking “reversal” surgeries are heading to a clinic in Serbia, where Professor Misoslav Djordjevic has been performing them for five years at the Belgrade Center for Genital Reconstructive Surgery.

A specialist in genital reconstruction with 20 years of experience, Prof Djordjevic began conducting the innovative procedures after a transgender patient who had undergone surgery to remove male genitalia requested a reversal.

It's by no means a common practice. He has performed just 14 surgeries to date and is currently in the process of treating two “reversal” patients, reports The Daily Telegraph , explaining that the procedure is extremely complex and can cost up to €18,000 (£15,965).

- Parents hit out at school's 'political agenda' over transgender pupil

However, his services aren't easily-accessed. Djordjevic will only treat patients who have undergone a full one-year-long psychiatric evaluation and he stresses the importance of post-surgery aftercare, revealing that he remains in contact with the majority of his patients.

It's not simply a case of people regretting their decision, explains James Morton, manager at the Scottish Trans Alliance , who told The Independent that a range of factors could catalyse the desire for a gender reversal including unusual surgical complications, being worn down by transphobic harassment, family rejection, or developing religious or political beliefs that being transgender is unacceptable.

"If a person has regret about undergoing gender reassignment, it is especially important that they receive counselling and in-depth assessment before undergoing any surgery to attempt partial reversal as their chance of regretting further surgery could be even higher," he said.

- What the legalisation of gay sex 50 years ago means to LGBT people now

"Any further NHS surgery is determined on an individualised case by case basis because the numbers are so tiny."

So far, Djordjevic has exclusively treated transgender females who have asked to recreate their male genitalia.

Known as phalloplasty, the procedure entails the construction of a penis from skin taken from the groin, abdomen or thigh. Though the surgery produces aesthetic results, many mistakenly assume that it will ultimately render one’s genitalia physically futile.

However, a 2013 study revealed that the introduction of penile stiffeners has allowed some plastic surgeons to create a fully functioning organ.

- We need more clothing sections than 'men's' and 'women's' says tailor

It is a much more risky procedure than its male to female counterpart, vaginoplasty, whereby the testicles are removed and the skin of the penis is used to artificially create a vagina.

Whilst awareness of non-binary issues has increased in recent years, gender reassignment remains a severely under researched topic, so much so that the NHS has produced an online e-learning guide to GPs who might be unfamiliar with gender dysphoria.

The severe lack of understanding surrounding the topic - and its reversal counterpart - became particularly prevalent last week, when a proposed study to explore why transsexual people may want to “detransition” was reportedly shut down by Bath Spa University so as “not to offend people.”

- Trans artist helps break down period stigma with bold post

“The fundamental reason given was that it might cause criticism of the research on social media and criticism of the research would be criticism of the university and they also added it was better not to offend people,” James Caspian, the psychotherapist behind the proposed research, told BBC Radio 4 .

He confessed to being “astonished” at the university’s decision.

As of 30 August, there were 213 patients on the list for gender reassignment surgery at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust .

At present, there are no statistics regarding gender reversal surgeries in the UK.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

New to The Independent?

Or if you would prefer:

Want an ad-free experience?

Hi {{indy.fullName}}

- My Independent Premium

- Account details

- Help centre

May 12, 2022

What the Science on Gender-Affirming Care for Transgender Kids Really Shows

Laws that ban gender-affirming treatment ignore the wealth of research demonstrating its benefits for trans people’s health

By Heather Boerner

As attacks against transgender kids increase in the U.S., Minnesotans hold a rally at the state’s capitol in Saint Paul in March 2022 to support trans kids in Minnesota and Texas and around the country.

Michael Siluk/UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Editor’s Note (3/30/23): This article from May 2022 is being republished to highlight the ways that ongoing anti-trans legislation is harmful and unscientific.

For the first 40 years of their life, Texas resident Kelly Fleming spent a portion of most years in a deep depression. As an adult, Fleming—who uses they/them pronouns and who asked to use a pseudonym to protect their safety—would shave their face in the shower with the lights off so neither they nor their wife would have to confront the reality of their body.

What Fleming was experiencing, although they did not know it at the time, was gender dysphoria : the acute and chronic distress of living in a body that does not reflect one’s gender and the desire to have bodily characteristics of that gender. While in therapy, Fleming discovered research linking access to gender-affirming hormone therapy with reduced depression in transgender people. They started a very low dose of estradiol, and the depression episodes became shorter, less frequent and less intense. Now they look at their body with joy.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

So when Fleming sees what authorities in Texas , Alabama , Florida and other states are doing to bar transgender teens and children from receiving gender-affirming medical care, it infuriates them. And they are worried for their children, ages 12 and 14, both of whom are agender—a identity on the transgender spectrum that is neither masculine nor feminine.

“I’m just so excited to see them being able to present themselves in a way that makes them happy,” Fleming says. “They are living their best life regardless of what others think, and that’s a privilege that I did not get to have as a younger person.”

Laws Based on “Completely Wrong” Information

Currently more than a dozen state legislatures or administrations are considering—or have already passed—laws banning health care for transgender young people. On April 20 the Florida Department of Health issued guidance to withhold such gender-affirming care. This includes social gender transitioning—acknowledging that a young person is trans, using their correct pronouns and name, and supporting their desire to live publicly as the gender of their experience rather than their sex assigned at birth. This comes nearly two months after Texas Governor Greg Abbott issued an order for the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services to investigate for child abuse parents who allow their transgender preteens and teenagers to receive medical care. Alabama recently passed SB 184 , which would make it a felony to provide gender-affirming medical care to transgender minors. In Alabama, a “minor” is defined as anyone 19 or younger.

If such laws go ahead, 58,200 teens in the U.S. could lose access to or never receive gender-affirming care, according to the Williams Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles. A decade of research shows such treatment reduces depression, suicidality and other devastating consequences of trans preteens and teens being forced to undergo puberty in the sex they were assigned at birth).

The bills are based on “information that’s completely wrong,” says Michelle Forcier, a pediatrician and professor of pediatrics at Brown University. Forcier literally helped write the book on how to provide evidence-based gender care to young people. She is also an assistant dean of admissions at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University. Those laws “are absolutely, absolutely incorrect” about the science of gender-affirming care for young people, she says. “[Inaccurate information] is there to create drama. It’s there to make people take a side.”

The truth is that data from more than a dozen studies of more than 30,000 transgender and gender-diverse young people consistently show that access to gender-affirming care is associated with better mental health outcomes—and that lack of access to such care is associated with higher rates of suicidality, depression and self-harming behavior. (Gender diversity refers to the extent to which a person’s gendered behaviors, appearance and identities are culturally incongruent with the sex they were assigned at birth. Gender-diverse people can identify along the transgender spectrum, but not all do.) Major medical organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) , the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , the Endocrine Society , the American Medical Association , the American Psychological Association and the American Psychiatric Association , have published policy statements and guidelines on how to provide age-appropriate gender-affirming care. All of those medical societies find such care to be evidence-based and medically necessary.

AAP and Endocrine Society guidelines call for developmentally appropriate care, and that means no puberty blockers or hormones until young people are already undergoing puberty for their sex assigned at birth. For one thing, “there are no hormonal differences among prepubertal children,” says Joshua Safer, executive director of the Mount Sinai Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery in New York City and co-author of the Endocrine Society’s guidelines. Those guidelines provide the option of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues (GnRHas), which block the release of sex hormones, once young people are already into the second of five puberty stages—marked by breast budding and pubic hair. These are offered only if a teen is not ready to make decisions about puberty. Access to gender-affirming hormones and potential access to gender-affirming surgery is available at age 16—and then, in the case of transmasculine youth, only mastectomy, also known as top surgery. The Endocrine Society does not recommend genital surgery for minors.

Before puberty, gender-affirming care is about supporting the process of gender development rather than directing children through a specific course of gender transition or maintenance of cisgender presentation, says Jason Rafferty, co-author of AAP’s policy statement on gender-affirming care and a pediatrician and psychiatrist at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Rhode Island. “The current research suggests that, rather than predicting or preventing who a child might become, it’s better to value them for who they are now—even at a young age,” Rafferty says.

A Safe Environment to Explore Gender

A 2021 systematic review of 44 peer-reviewed studies found that parent connectedness, measured by a six-question scale asking about such things as how safe young people feel confiding in their guardians or how cared for they feel in the family, is associated with greater resilience among teens and young adults who are transgender or gender-diverse. Rafferty says he sees his role with regard to prepubertal children as offering a safe environment for the child to explore their gender and for parents to ask questions. “The gender-affirming approach is not some railroad of people to hormones and surgery,” Safer says. “It is talking and watching and being conservative.”

Only once children are older, and if the incongruence between the sex assigned to them at birth and their experienced gender has persisted, does discussion of medical transition occur. First a gender therapist has to diagnose the young person with gender dysphoria .

After a gender dysphoria diagnosis—and only if earlier conversations suggest that hormones are indicated—guidelines call for discussion of fertility, puberty suppression and hormones. Puberty-suppressing medications have been used for decades for cisgender children who start puberty early, but they are not meant to be used indefinitely. The Endocrine Society guidelines recommend a maximum of two years on GnRHa therapy to allow more time for children to form their gender identity before undergoing puberty for their sex assigned at birth, the effects of which are irreversible.

“[Puberty blockers] are part of the process of ‘do no harm,’” Forcier says, referencing a popular phrase that describes the Hippocratic Oath, which many physicians recite a version of before they begin to practice.

Hormone blocker treatment may have side effects. A 2015 longitudinal observational cohort study of 34 transgender young people found that, by the time the participants were 22 years old, trans women experienced a decrease in bone mineral density. A 2020 study of puberty suppression in gender-diverse and transgender young people found that those who started puberty blockers in early puberty had lower bone mineral density before the start of treatment than the public at large. This suggests, the authors wrote, that GnRHa use may not be the cause of low bone mineral density for these young people. Instead they found that lack of exercise was a primary factor in low bone-mineral density, especially among transgender girls.

Other side effects of GnRHa therapy include weight gain, hot flashes and mood swings. But studies have found that these side effects—and puberty delay itself—are reversible , Safer says.

Gender-affirming hormone therapy often involves taking an androgen blocker (a chemical that blocks the release of testosterone and other androgenic hormones) and estrogen in transfeminine teens, and testosterone supplementation in transmasculine teens. Such hormones may be associated with some physiological changes for adult transgender people. For instance, transfeminine people taking estrogen see their so-called “good” cholesterol increase. By contrast, transmasculine people taking testosterone see their good cholesterol decrease. Some studies have hinted at effects on bone mineral density, but these are complicated and also depend on personal, family history, exercise, and many other factors in addition to hormones.”

And while some critics point to decade-old study and older studies suggesting very few young people persist in transgender identity into late adolescence and adulthood, Forcier says the data are “misleading and not accurate.” A recent review detailed methodological problems with some of these studies . New research in 17,151 people who had ever socially transitioned found that 86.9 percent persisted in their gender identity. Of the 2,242 people who reported that they reverted to living as the gender associated with the sex they were assigned at birth, just 15.9 percent said they did so because of internal factors such as questioning their experienced gender but also because of fear, mental health issues and suicide attempts. The rest reported the cause was social, economic and familial stigma and discrimination. A third reported that they ceased living openly as a trans person because doing so was “just too hard for me.”

The Harms of Denying Care

Data suggest the effects of denying that care are worse than whatever side effects result from delaying sex-assigned-at-birth puberty. And medical society guidelines conclude that the benefits of gender-affirming care outweigh the risks. Without gender-affirming hormone therapy, cisgender hormones take over, forcing body changes that can be permanent and distressing.

A 2020 study of 300 gender-incongruent young people found that mental distress—including self-harm, suicidal thoughts and depression— increased as the children were made to proceed with puberty according to their assigned sex. By the time 184 older teens (with a median age of 16) reached the stage in which transgender boys began their periods and grew breasts and transgender girls’ voice dropped and facial hair began to appear, 46 percent had been diagnosed with depression, 40 percent had self-harmed, 52 percent had considered suicide, and 17 percent had attempted it—rates significantly higher than those of gender-incongruent children who were a median of 13.9 years old or of cisgender kids their own age.

Conversely, access to gender-affirming hormones in adolescence appears to have a protective effect. In one study, researchers followed 104 teens and young adults for a year and asked them about their depression, anxiety and suicidality at the time they started receiving hormones or puberty blockers and again at the three-month, six-month and one-year mark. At the beginning of the study, which was published in JAMA Network Open in February 2022, more than half of the respondents reported moderate to severe depression, half reported moderate to severe anxiety, and 43.3 percent reported thoughts of self-harm or suicide in the past two weeks.

But when the researchers analyzed the results based on the kind of gender-affirming care the teens had received, they found that those who had access to puberty blockers or gender-affirming hormones were 60 percent less likely to experience moderate to severe depression. And those with access to the medical treatments were 73 percent less likely to contemplate self-harm or suicide.

“Delays in prescribing puberty blockers and hormones may in fact worsen mental health symptoms for trans youth,” says Diana Tordoff, an epidemiology graduate student at the University of Washington and co-author of the study.

That effect may be lifelong. A 2022 study of more than 21,000 transgender adults showed that just 41 percent of adults who wanted hormone therapy received it, and just 2.3 percent had access to it in adolescence. When researchers looked at rates of suicidal thinking over the past year in these same adults, they found that access to hormone therapy in early adolescence was associated with a 60 percent reduction in suicidality in the past year and that access in late adolescence was associated with a 50 percent reduction.

For Fleming’s kids in Texas, gender-affirming hormones are not currently part of the discussion; not all trans people desire hormones or surgery to feel affirmed in their gender. But Fleming is already looking at jobs in other states to protect their children’s access to such care, should they change their mind. “Getting your body closer to the gender [you] identify with—that is what helps the dysphoria,” Fleming says. “And not giving people the opportunity to do that, making it harder for them to do that, is what has made the suicide rate among transgender people so high. We just—trans people are just trying to survive.”

IF YOU NEED HELP If you or someone you know is struggling or having thoughts of suicide, help is available. Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 (TALK), use the online Lifeline Chat or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741.

- Search the site GO Please fill out this field.

- Newsletters

- Mental Health

- Social and Public Health

What Is Gender Affirmation Surgery?

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/KP-Headshot-IMG_1661-0d48c6ea46f14ab19a91e7b121b49f59.jpg)

A gender affirmation surgery allows individuals, such as those who identify as transgender or nonbinary, to change one or more of their sex characteristics. This type of procedure offers a person the opportunity to have features that align with their gender identity.

For example, this type of surgery may be a transgender surgery like a male-to-female or female-to-male surgery. Read on to learn more about what masculinizing, feminizing, and gender-nullification surgeries may involve, including potential risks and complications.

Why Is Gender Affirmation Surgery Performed?

A person may have gender affirmation surgery for different reasons. They may choose to have the surgery so their physical features and functional ability align more closely with their gender identity.

For example, one study found that 48,019 people underwent gender affirmation surgeries between 2016 and 2020. Most procedures were breast- and chest-related, while the remaining procedures concerned genital reconstruction or facial and cosmetic procedures.

In some cases, surgery may be medically necessary to treat dysphoria. Dysphoria refers to the distress that transgender people may experience when their gender identity doesn't match their sex assigned at birth. One study found that people with gender dysphoria who had gender affirmation surgeries experienced:

- Decreased antidepressant use

- Decreased anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation

- Decreased alcohol and drug abuse

However, these surgeries are only performed if appropriate for a person's case. The appropriateness comes about as a result of consultations with mental health professionals and healthcare providers.

Transgender vs Nonbinary

Transgender and nonbinary people can get gender affirmation surgeries. However, there are some key ways that these gender identities differ.

Transgender is a term that refers to people who have gender identities that aren't the same as their assigned sex at birth. Identifying as nonbinary means that a person doesn't identify only as a man or a woman. A nonbinary individual may consider themselves to be:

- Both a man and a woman

- Neither a man nor a woman

- An identity between or beyond a man or a woman

Hormone Therapy

Gender-affirming hormone therapy uses sex hormones and hormone blockers to help align the person's physical appearance with their gender identity. For example, some people may take masculinizing hormones.

"They start growing hair, their voice deepens, they get more muscle mass," Heidi Wittenberg, MD , medical director of the Gender Institute at Saint Francis Memorial Hospital in San Francisco and director of MoZaic Care Inc., which specializes in gender-related genital, urinary, and pelvic surgeries, told Health .

Types of hormone therapy include:

- Masculinizing hormone therapy uses testosterone. This helps to suppress the menstrual cycle, grow facial and body hair, increase muscle mass, and promote other male secondary sex characteristics.

- Feminizing hormone therapy includes estrogens and testosterone blockers. These medications promote breast growth, slow the growth of body and facial hair, increase body fat, shrink the testicles, and decrease erectile function.

- Non-binary hormone therapy is typically tailored to the individual and may include female or male sex hormones and/or hormone blockers.

It can include oral or topical medications, injections, a patch you wear on your skin, or a drug implant. The therapy is also typically recommended before gender affirmation surgery unless hormone therapy is medically contraindicated or not desired by the individual.

Masculinizing Surgeries

Masculinizing surgeries can include top surgery, bottom surgery, or both. Common trans male surgeries include:

- Chest masculinization (breast tissue removal and areola and nipple repositioning/reshaping)

- Hysterectomy (uterus removal)

- Metoidioplasty (lengthening the clitoris and possibly extending the urethra)

- Oophorectomy (ovary removal)

- Phalloplasty (surgery to create a penis)

- Scrotoplasty (surgery to create a scrotum)

Top Surgery

Chest masculinization surgery, or top surgery, often involves removing breast tissue and reshaping the areola and nipple. There are two main types of chest masculinization surgeries:

- Double-incision approach : Used to remove moderate to large amounts of breast tissue, this surgery involves two horizontal incisions below the breast to remove breast tissue and accentuate the contours of pectoral muscles. The nipples and areolas are removed and, in many cases, resized, reshaped, and replaced.

- Short scar top surgery : For people with smaller breasts and firm skin, the procedure involves a small incision along the lower half of the areola to remove breast tissue. The nipple and areola may be resized before closing the incision.

Metoidioplasty

Some trans men elect to do metoidioplasty, also called a meta, which involves lengthening the clitoris to create a small penis. Both a penis and a clitoris are made of the same type of tissue and experience similar sensations.

Before metoidioplasty, testosterone therapy may be used to enlarge the clitoris. The procedure can be completed in one surgery, which may also include:

- Constructing a glans (head) to look more like a penis

- Extending the urethra (the tube urine passes through), which allows the person to urinate while standing

- Creating a scrotum (scrotoplasty) from labia majora tissue

Phalloplasty

Other trans men opt for phalloplasty to give them a phallic structure (penis) with sensation. Phalloplasty typically requires several procedures but results in a larger penis than metoidioplasty.

The first and most challenging step is to harvest tissue from another part of the body, often the forearm or back, along with an artery and vein or two, to create the phallus, Nicholas Kim, MD, assistant professor in the division of plastic and reconstructive surgery in the department of surgery at the University of Minnesota Medical School in Minneapolis, told Health .

Those structures are reconnected under an operative microscope using very fine sutures—"thinner than our hair," said Dr. Kim. That surgery alone can take six to eight hours, he added.

In a separate operation, called urethral reconstruction, the surgeons connect the urinary system to the new structure so that urine can pass through it, said Dr. Kim. Urethral reconstruction, however, has a high rate of complications, which include fistulas or strictures.

According to Dr. Kim, some trans men prefer to skip that step, especially if standing to urinate is not a priority. People who want to have penetrative sex will also need prosthesis implant surgery.

Hysterectomy and Oophorectomy

Masculinizing surgery often includes the removal of the uterus (hysterectomy) and ovaries (oophorectomy). People may want a hysterectomy to address their dysphoria, said Dr. Wittenberg, and it may be necessary if their gender-affirming surgery involves removing the vagina.

Many also opt for an oophorectomy to remove the ovaries, almond-shaped organs on either side of the uterus that contain eggs and produce female sex hormones. In this case, oocytes (eggs) can be extracted and stored for a future surrogate pregnancy, if desired. However, this is a highly personal decision, and some trans men choose to keep their uterus to preserve fertility.

Feminizing Surgeries

Surgeries are often used to feminize facial features, enhance breast size and shape, reduce the size of an Adam’s apple , and reconstruct genitals. Feminizing surgeries can include:

- Breast augmentation

- Facial feminization surgery

- Penis removal (penectomy)

- Scrotum removal (scrotectomy)

- Testicle removal (orchiectomy)

- Tracheal shave (chondrolaryngoplasty) to reduce an Adam's apple

- Vaginoplasty

- Voice feminization

Breast Augmentation

Top surgery, also known as breast augmentation or breast mammoplasty, is often used to increase breast size for a more feminine appearance. The procedure can involve placing breast implants, tissue expanders, or fat from other parts of the body under the chest tissue.

Breast augmentation can significantly improve gender dysphoria. Studies show most people who undergo top surgery are happier, more satisfied with their chest, and would undergo the surgery again.

Most surgeons recommend 12 months of feminizing hormone therapy before breast augmentation. Since hormone therapy itself can lead to breast tissue development, transgender women may or may not decide to have surgical breast augmentation.

Facial Feminization and Adam's Apple Removal

Facial feminization surgery (FFS) is a series of plastic surgery procedures that reshape the forehead, hairline, eyebrows, nose, cheeks, and jawline. Nonsurgical treatments like cosmetic fillers, botox, fat grafting, and liposuction may also be used to create a more feminine appearance.

Some trans women opt for chondrolaryngoplasty, also known as a tracheal shave. The procedure reduces the size of the Adam's apple, an area of cartilage around the larynx (voice box) that tends to be larger in people assigned male at birth.

Vulvoplasty and Vaginoplasty

As for bottom surgery, there are various feminizing procedures from which to choose. Vulvoplasty (to create external genitalia without a vagina) or vaginoplasty (to create a vulva and vaginal canal) are two of the most common procedures.

Dr. Wittenberg noted that people might undergo six to 12 months of electrolysis or laser hair removal before surgery to remove pubic hair from the skin that will be used for the vaginal lining.

Surgeons have different techniques for creating a vaginal canal. A common one is a penile inversion, where the masculine structures are emptied and inverted into a created cavity, explained Dr. Kim. Vaginoplasty may be done in one or two stages, said Dr. Wittenberg, and the initial recovery is three months—but it will be a full year until people see results.

Surgical removal of the penis or penectomy is sometimes used in feminization treatment. This can be performed along with an orchiectomy and scrotectomy.

However, a total penectomy is not commonly used in feminizing surgeries . Instead, many people opt for penile-inversion surgery, a technique that hollows out the penis and repurposes the tissue to create a vagina during vaginoplasty.

Orchiectomy and Scrotectomy

An orchiectomy is a surgery to remove the testicles —male reproductive organs that produce sperm. Scrotectomy is surgery to remove the scrotum, that sac just below the penis that holds the testicles.

However, some people opt to retain the scrotum. Scrotum skin can be used in vulvoplasty or vaginoplasty, surgeries to construct a vulva or vagina.

Other Surgical Options

Some gender non-conforming people opt for other types of surgeries. This can include:

- Gender nullification procedures

- Penile preservation vaginoplasty

- Vaginal preservation phalloplasty

Gender Nullification

People who are agender or asexual may opt for gender nullification, sometimes called nullo. This involves the removal of all sex organs. The external genitalia is removed, leaving an opening for urine to pass and creating a smooth transition from the abdomen to the groin.

Depending on the person's sex assigned at birth, nullification surgeries can include:

- Breast tissue removal

- Nipple and areola augmentation or removal

Penile Preservation Vaginoplasty

Some gender non-conforming people assigned male at birth want a vagina but also want to preserve their penis, said Dr. Wittenberg. Often, that involves taking skin from the lining of the abdomen to create a vagina with full depth.

Vaginal Preservation Phalloplasty

Alternatively, a patient assigned female at birth can undergo phalloplasty (surgery to create a penis) and retain the vaginal opening. Known as vaginal preservation phalloplasty, it is often used as a way to resolve gender dysphoria while retaining fertility.

The recovery time for a gender affirmation surgery will depend on the type of surgery performed. For example, healing for facial surgeries may last for weeks, while transmasculine bottom surgery healing may take months.

Your recovery process may also include additional treatments or therapies. Mental health support and pelvic floor physiotherapy are a few options that may be needed or desired during recovery.

Risks and Complications

The risk and complications of gender affirmation surgeries will vary depending on which surgeries you have. Common risks across procedures could include:

- Anesthesia risks

- Hematoma, which is bad bruising

- Poor incision healing

Complications from these procedures may be:

- Acute kidney injury

- Blood transfusion

- Deep vein thrombosis, which is blood clot formation

- Pulmonary embolism, blood vessel blockage for vessels going to the lung

- Rectovaginal fistula, which is a connection between two body parts—in this case, the rectum and vagina

- Surgical site infection

- Urethral stricture or stenosis, which is when the urethra narrows

- Urinary tract infection (UTI)

- Wound disruption

What To Consider

It's important to note that an individual does not need surgery to transition. If the person has surgery, it is usually only one part of the transition process.

There's also psychotherapy . People may find it helpful to work through the negative mental health effects of dysphoria. Typically, people seeking gender affirmation surgery must be evaluated by a qualified mental health professional to obtain a referral.

Some people may find that living in their preferred gender is all that's needed to ease their dysphoria. Doing so for one full year prior is a prerequisite for many surgeries.

All in all, the entire transition process—living as your identified gender, obtaining mental health referrals, getting insurance approvals, taking hormones, going through hair removal, and having various surgeries—can take years, healthcare providers explained.

A Quick Review

Whether you're in the process of transitioning or supporting someone who is, it's important to be informed about gender affirmation surgeries. Gender affirmation procedures often involve multiple surgeries, which can be masculinizing, feminizing, or gender-nullifying in nature.

It is a highly personalized process that looks different for each person and can often take several months or years. The procedures also vary regarding risks and complications, so consultations with healthcare providers and mental health professionals are essential before having these procedures.

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Gender affirmation surgeries .

Wright JD, Chen L, Suzuki Y, Matsuo K, Hershman DL. National estimates of gender-affirming surgery in the US . JAMA Netw Open . 2023;6(8):e2330348-e2330348. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.30348

Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8 . Int J Transgend Health . 2022;23(S1):S1-S260. doi:10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644

Chou J, Kilmer LH, Campbell CA, DeGeorge BR, Stranix JY. Gender-affirming surgery improves mental health outcomes and decreases anti-depressant use in patients with gender dysphoria . Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open . 2023;11(6 Suppl):1. doi:10.1097/01.GOX.0000944280.62632.8c

Human Rights Campaign. Get the facts on gender-affirming care .

Human Rights Campaign. Transgender and non-binary people FAQ .

Unger CA. Hormone therapy for transgender patients . Transl Androl Urol . 2016;5(6):877–84. doi:10.21037/tau.2016.09.04

Richards JE, Hawley RS. Chapter 8: Sex Determination: How Genes Determine a Developmental Choice . In: Richards JE, Hawley RS, eds. The Human Genome . 3rd ed. Academic Press; 2011: 273-298.

Randolph JF Jr. Gender-affirming hormone therapy for transgender females . Clin Obstet Gynecol . 2018;61(4):705-721. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000396

Cocchetti C, Ristori J, Romani A, Maggi M, Fisher AD. Hormonal treatment strategies tailored to non-binary transgender individuals . J Clin Med . 2020;9(6):1609. doi:10.3390/jcm9061609

Van Boerum MS, Salibian AA, Bluebond-Langner R, Agarwal C. Chest and facial surgery for the transgender patient . Transl Androl Urol . 2019;8(3):219-227. doi:10.21037/tau.2019.06.18

Djordjevic ML, Stojanovic B, Bizic M. Metoidioplasty: techniques and outcomes . Transl Androl Urol . 2019;8(3):248–53. doi:10.21037/tau.2019.06.12

Bordas N, Stojanovic B, Bizic M, Szanto A, Djordjevic ML. Metoidioplasty: surgical options and outcomes in 813 cases . Front Endocrinol . 2021;12:760284. doi:10.3389/fendo.2021.760284

Al-Tamimi M, Pigot GL, van der Sluis WB, et al. The surgical techniques and outcomes of secondary phalloplasty after metoidioplasty in transgender men: an international, multi-center case series . The Journal of Sexual Medicine . 2019;16(11):1849-1859. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.07.027

Waterschoot M, Hoebeke P, Verla W, et al. Urethral complications after metoidioplasty for genital gender affirming surgery . J Sex Med . 2021;18(7):1271–9. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.06.023

Nikolavsky D, Hughes M, Zhao LC. Urologic complications after phalloplasty or metoidioplasty . Clin Plast Surg . 2018;45(3):425–35. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2018.03.013

Nota NM, den Heijer M, Gooren LJ. Evaluation and treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender incongruent adults . In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., eds. Endotext . MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

Carbonnel M, Karpel L, Cordier B, Pirtea P, Ayoubi JM. The uterus in transgender men . Fertil Steril . 2021;116(4):931–5. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.07.005

Miller TJ, Wilson SC, Massie JP, Morrison SD, Satterwhite T. Breast augmentation in male-to-female transgender patients: Technical considerations and outcomes . JPRAS Open . 2019;21:63-74. doi:10.1016/j.jpra.2019.03.003

Claes KEY, D'Arpa S, Monstrey SJ. Chest surgery for transgender and gender nonconforming individuals . Clin Plast Surg . 2018;45(3):369–80. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2018.03.010

De Boulle K, Furuyama N, Heydenrych I, et al. Considerations for the use of minimally invasive aesthetic procedures for facial remodeling in transgender individuals . Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol . 2021;14:513-525. doi:10.2147/CCID.S304032

Asokan A, Sudheendran MK. Gender affirming body contouring and physical transformation in transgender individuals . Indian J Plast Surg . 2022;55(2):179-187. doi:10.1055/s-0042-1749099

Sturm A, Chaiet SR. Chondrolaryngoplasty-thyroid cartilage reduction . Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am . 2019;27(2):267–72. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2019.01.005

Chen ML, Reyblat P, Poh MM, Chi AC. Overview of surgical techniques in gender-affirming genital surgery . Transl Androl Urol . 2019;8(3):191-208. doi:10.21037/tau.2019.06.19

Wangjiraniran B, Selvaggi G, Chokrungvaranont P, Jindarak S, Khobunsongserm S, Tiewtranon P. Male-to-female vaginoplasty: Preecha's surgical technique . J Plast Surg Hand Surg . 2015;49(3):153-9. doi:10.3109/2000656X.2014.967253

Okoye E, Saikali SW. Orchiectomy . In: StatPearls [Internet] . Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

Salgado CJ, Yu K, Lalama MJ. Vaginal and reproductive organ preservation in trans men undergoing gender-affirming phalloplasty: technical considerations . J Surg Case Rep . 2021;2021(12):rjab553. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjab553

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. What should I expect during my recovery after facial feminization surgery?

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. What should I expect during my recovery after transmasculine bottom surgery?

de Brouwer IJ, Elaut E, Becker-Hebly I, et al. Aftercare needs following gender-affirming surgeries: findings from the ENIGI multicenter European follow-up study . The Journal of Sexual Medicine . 2021;18(11):1921-1932. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.08.005

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. What are the risks of transfeminine bottom surgery?

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. What are the risks of transmasculine top surgery?

Khusid E, Sturgis MR, Dorafshar AH, et al. Association between mental health conditions and postoperative complications after gender-affirming surgery . JAMA Surg . 2022;157(12):1159-1162. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2022.3917

Related Articles

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Tests & Procedures

- Feminizing hormone therapy

Feminizing hormone therapy typically is used by transgender women and nonbinary people to produce physical changes in the body that are caused by female hormones during puberty. Those changes are called secondary sex characteristics. This hormone therapy helps better align the body with a person's gender identity. Feminizing hormone therapy also is called gender-affirming hormone therapy.

Feminizing hormone therapy involves taking medicine to block the action of the hormone testosterone. It also includes taking the hormone estrogen. Estrogen lowers the amount of testosterone the body makes. It also triggers the development of feminine secondary sex characteristics. Feminizing hormone therapy can be done alone or along with feminizing surgery.

Not everybody chooses to have feminizing hormone therapy. It can affect fertility and sexual function, and it might lead to health problems. Talk with your health care provider about the risks and benefits for you.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Available Sexual Health Solutions at Mayo Clinic Store

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Why it's done

Feminizing hormone therapy is used to change the body's hormone levels. Those hormone changes trigger physical changes that help better align the body with a person's gender identity.

In some cases, people seeking feminizing hormone therapy experience discomfort or distress because their gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth or from their sex-related physical characteristics. This condition is called gender dysphoria.

Feminizing hormone therapy can:

- Improve psychological and social well-being.

- Ease psychological and emotional distress related to gender.

- Improve satisfaction with sex.

- Improve quality of life.

Your health care provider might advise against feminizing hormone therapy if you:

- Have a hormone-sensitive cancer, such as prostate cancer.

- Have problems with blood clots, such as when a blood clot forms in a deep vein, a condition called deep vein thrombosis, or a there's a blockage in one of the pulmonary arteries of the lungs, called a pulmonary embolism.

- Have significant medical conditions that haven't been addressed.

- Have behavioral health conditions that haven't been addressed.

- Have a condition that limits your ability to give your informed consent.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

Stay Informed with LGBTQ+ health content.

Receive trusted health information and answers to your questions about sexual orientation, gender identity, transition, self-expression, and LGBTQ+ health topics. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing to our LGBTQ+ newsletter.

You will receive the first newsletter in your inbox shortly. This will include exclusive health content about the LGBTQ+ community from Mayo Clinic.

If you don't receive our email within 5 minutes, check your SPAM folder, then contact us at [email protected] .

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

Research has found that feminizing hormone therapy can be safe and effective when delivered by a health care provider with expertise in transgender care. Talk to your health care provider about questions or concerns you have regarding the changes that will happen in your body as a result of feminizing hormone therapy.

Complications can include:

- Blood clots in a deep vein or in the lungs

- Heart problems

- High levels of triglycerides, a type of fat, in the blood

- High levels of potassium in the blood

- High levels of the hormone prolactin in the blood

- Nipple discharge

- Weight gain

- Infertility

- High blood pressure

- Type 2 diabetes

Evidence suggests that people who take feminizing hormone therapy may have an increased risk of breast cancer when compared to cisgender men — men whose gender identity aligns with societal norms related to their sex assigned at birth. But the risk is not greater than that of cisgender women.

To minimize risk, the goal for people taking feminizing hormone therapy is to keep hormone levels in the range that's typical for cisgender women.

Feminizing hormone therapy might limit your fertility. If possible, it's best to make decisions about fertility before starting treatment. The risk of permanent infertility increases with long-term use of hormones. That is particularly true for those who start hormone therapy before puberty begins. Even after stopping hormone therapy, your testicles might not recover enough to ensure conception without infertility treatment.

If you want to have biological children, talk to your health care provider about freezing your sperm before you start feminizing hormone therapy. That procedure is called sperm cryopreservation.

How you prepare

Before you start feminizing hormone therapy, your health care provider assesses your health. This helps address any medical conditions that might affect your treatment. The evaluation may include:

- A review of your personal and family medical history.

- A physical exam.

- A review of your vaccinations.

- Screening tests for some conditions and diseases.

- Identification and management, if needed, of tobacco use, drug use, alcohol use disorder, HIV or other sexually transmitted infections.

- Discussion about sperm freezing and fertility.

You also might have a behavioral health evaluation by a provider with expertise in transgender health. The evaluation may assess:

- Gender identity.

- Gender dysphoria.

- Mental health concerns.

- Sexual health concerns.

- The impact of gender identity at work, at school, at home and in social settings.

- Risky behaviors, such as substance use or use of unapproved silicone injections, hormone therapy or supplements.

- Support from family, friends and caregivers.

- Your goals and expectations of treatment.

- Care planning and follow-up care.

People younger than age 18, along with a parent or guardian, should see a medical care provider and a behavioral health provider with expertise in pediatric transgender health to discuss the risks and benefits of hormone therapy and gender transitioning in that age group.

What you can expect

You should start feminizing hormone therapy only after you've had a discussion of the risks and benefits as well as treatment alternatives with a health care provider who has expertise in transgender care. Make sure you understand what will happen and get answers to any questions you may have before you begin hormone therapy.

Feminizing hormone therapy typically begins by taking the medicine spironolactone (Aldactone). It blocks male sex hormone receptors — also called androgen receptors. This lowers the amount of testosterone the body makes.

About 4 to 8 weeks after you start taking spironolactone, you begin taking estrogen. This also lowers the amount of testosterone the body makes. And it triggers physical changes in the body that are caused by female hormones during puberty.

Estrogen can be taken several ways. They include a pill and a shot. There also are several forms of estrogen that are applied to the skin, including a cream, gel, spray and patch.

It is best not to take estrogen as a pill if you have a personal or family history of blood clots in a deep vein or in the lungs, a condition called venous thrombosis.

Another choice for feminizing hormone therapy is to take gonadotropin-releasing hormone (Gn-RH) analogs. They lower the amount of testosterone your body makes and might allow you to take lower doses of estrogen without the use of spironolactone. The disadvantage is that Gn-RH analogs usually are more expensive.

After you begin feminizing hormone therapy, you'll notice the following changes in your body over time:

- Fewer erections and a decrease in ejaculation. This will begin 1 to 3 months after treatment starts. The full effect will happen within 3 to 6 months.

- Less interest in sex. This also is called decreased libido. It will begin 1 to 3 months after you start treatment. You'll see the full effect within 1 to 2 years.

- Slower scalp hair loss. This will begin 1 to 3 months after treatment begins. The full effect will happen within 1 to 2 years.

- Breast development. This begins 3 to 6 months after treatment starts. The full effect happens within 2 to 3 years.

- Softer, less oily skin. This will begin 3 to 6 months after treatment starts. That's also when the full effect will happen.

- Smaller testicles. This also is called testicular atrophy. It begins 3 to 6 months after the start of treatment. You'll see the full effect within 2 to 3 years.

- Less muscle mass. This will begin 3 to 6 months after treatment starts. You'll see the full effect within 1 to 2 years.

- More body fat. This will begin 3 to 6 months after treatment starts. The full effect will happen within 2 to 5 years.

- Less facial and body hair growth. This will begin 6 to 12 months after treatment starts. The full effect happens within three years.

Some of the physical changes caused by feminizing hormone therapy can be reversed if you stop taking it. Others, such as breast development, cannot be reversed.

While on feminizing hormone therapy, you meet regularly with your health care provider to:

- Keep track of your physical changes.

- Monitor your hormone levels. Over time, your hormone dose may need to change to ensure you are taking the lowest dose necessary to get the physical effects that you want.

- Have blood tests to check for changes in your cholesterol, blood sugar, blood count, liver enzymes and electrolytes that could be caused by hormone therapy.

- Monitor your behavioral health.

You also need routine preventive care. Depending on your situation, this may include:

- Breast cancer screening. This should be done according to breast cancer screening recommendations for cisgender women your age.

- Prostate cancer screening. This should be done according to prostate cancer screening recommendations for cisgender men your age.

- Monitoring bone health. You should have bone density assessment according to the recommendations for cisgender women your age. You may need to take calcium and vitamin D supplements for bone health.

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies of tests and procedures to help prevent, detect, treat or manage conditions.

Feminizing hormone therapy care at Mayo Clinic

- Tangpricha V, et al. Transgender women: Evaluation and management. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Oct. 10, 2022.

- Erickson-Schroth L, ed. Medical transition. In: Trans Bodies, Trans Selves: A Resource by and for Transgender Communities. 2nd ed. Kindle edition. Oxford University Press; 2022. Accessed Oct. 10, 2022.

- Coleman E, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. International Journal of Transgender Health. 2022; doi:10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644.

- AskMayoExpert. Gender-affirming hormone therapy (adult). Mayo Clinic; 2022.

- Nippoldt TB (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. Sept. 29, 2022.

- Gender dysphoria

- Doctors & Departments

- Care at Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Let’s celebrate our doctors!

Join us in celebrating and honoring Mayo Clinic physicians on March 30th for National Doctor’s Day.

Gender reassignment surgery: an overview

Affiliation.

- 1 Gender Surgery Unit, Charing Cross Hospital, Imperial College NHS Trust, 179-183 Fulham Palace Road, London W6 8QZ, UK.

- PMID: 21487386

- DOI: 10.1038/nrurol.2011.46

Gender reassignment (which includes psychotherapy, hormonal therapy and surgery) has been demonstrated as the most effective treatment for patients affected by gender dysphoria (or gender identity disorder), in which patients do not recognize their gender (sexual identity) as matching their genetic and sexual characteristics. Gender reassignment surgery is a series of complex surgical procedures (genital and nongenital) performed for the treatment of gender dysphoria. Genital procedures performed for gender dysphoria, such as vaginoplasty, clitorolabioplasty, penectomy and orchidectomy in male-to-female transsexuals, and penile and scrotal reconstruction in female-to-male transsexuals, are the core procedures in gender reassignment surgery. Nongenital procedures, such as breast enlargement, mastectomy, facial feminization surgery, voice surgery, and other masculinization and feminization procedures complete the surgical treatment available. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health currently publishes and reviews guidelines and standards of care for patients affected by gender dysphoria, such as eligibility criteria for surgery. This article presents an overview of the genital and nongenital procedures available for both male-to-female and female-to-male gender reassignment.

Publication types

- Plastic Surgery Procedures / methods*

- Plastic Surgery Procedures / psychology

- Postoperative Complications / prevention & control

- Postoperative Complications / psychology

- Sex Reassignment Surgery / methods*

- Sex Reassignment Surgery / psychology

- Transsexualism / diagnosis

- Transsexualism / psychology

- Transsexualism / surgery*

- Open access

- Published: 25 April 2022

Patient reported outcomes in genital gender-affirming surgery: the time is now

- Nnenaya Agochukwu-Mmonu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4620-8897 1 , 2 ,

- Asa Radix 3 , 4 ,

- Lee Zhao 2 ,

- Danil Makarov 1 , 2 ,

- Rachel Bluebond-Langner 5 ,

- A. Mark Fendrick 6 , 7 ,

- Elijah Castle 1 , 2 &

- Carolyn Berry 2 , 3

Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes volume 6 , Article number: 39 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

2898 Accesses

6 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Transgender and non-binary (TGNB) individuals often experience gender dysphoria. TGNB individuals with gender dysphoria may undergo genital gender-affirming surgery including vaginoplasty, phalloplasty, or metoidioplasty so that their genitourinary anatomy is congruent with their experienced gender. Given decreasing social stigma and increasing coverage from private and public payers, there has been a rapid increase in genital gender-affirming surgery in the past few years. As the incidence of genital gender-affirming surgery increases, a concurrent increase in the development and utilization of patient reported outcome measurement tools is critical. To date, there is no systematic way to assess and measure patients’ perspectives on their surgeries nor is there a validated measure to capture patient reported outcomes for TGNB individuals undergoing genital gender-affirming surgery. Without a systematic way to assess and measure patients’ perspectives on their care, there may be fragmentation of care. This fragmentation may result in challenges to ensure patients’ goals are at the forefront of shared- decision making. As we aim to increase access to surgical care for TGNB individuals, it is important to ensure this care is patient-centered and high-quality. The development of patient-reported outcomes for patients undergoing genital gender-affirming surgery is the first step in ensuring high quality patient-centered care. Herein, we discuss the critical need for development of validated patient reported outcome measures for transgender and non-binary patients undergoing genital reconstruction. We also propose a model of patient-engaged patient reported outcome measure development.

Approximately 1 in every 200 US adults, roughly 1.4 million Americans, identify as transgender [ 1 ]. Some transgender and non-binary (TGNB) individuals experience gender dysphoria, which is discomfort, distress, physical, and psychological impairment that results from an incongruence between an individual’s gender identity and their sex assigned at birth [ 2 ]. TGNB individuals who experience gender dysphoria may seek medical and/or surgical interventions so that their physical features are congruent with their gender identity. In the past decade increased recognition of gender dysphoria, decreasing social stigma towards TGNB individuals, and increasing insurance coverage have led to a three-fold increase in gender-affirming surgeries [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. Of gender-affirming surgeries, the incidence of genital gender-affirming surgery—vaginoplasty, phalloplasty and metoidioplasty—has steeply increased and is likely the most common inpatient gender-affirming surgery [ 7 ]. Although increased coverage has undoubtedly had many benefits for the TGNB community, to date, there have been few, if any, attempts to systematically assess patients’ perspectives on genital gender-affirming surgery. Without direct input from patients undergoing gender-affirming surgery, we cannot truly understand patients’ goals and preferences (e.g., sexual and aesthetic goals, quality of life) beyond amelioration of gender dysphoria, nor can we reliably assess the magnitude of benefits of gender-affirming surgery or prepare patients with realistic expectations of genital surgeries. Perhaps the most impactful result of a lack of explicit capture and incorporation of the patient perspective is the lack of shared decision-making and propagation of a paternalistic care model. This is evidenced by single-center studies, which have demonstrated evidence of decision-related regret and depending on an individuals’ goals, revision surgery [ 8 , 9 , 10 ]. There is also evidence that patients’ knowledge about outcomes after gender-affirming surgery is lacking and patients may have unrealistic expectations [ 11 ]. The current system of outcome reporting prioritizes clinical outcomes, which only captures physicians’ reports of outcomes, is subject to bias, does not include the patients’ perspective and, hence, are inadequate. The process of genital reconstruction is intensive and patients undertake significant risk to undergo life-changing genital gender-affirming surgery; there is an urgent need for patient-centered metrics. Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) are patient-centered metrics and represent a viable solution to these challenges and shortcomings.

PROMs developed by and for TGNB patients undergoing genital gender-affirming surgery are imperative to delivering high-value, high-quality, patient-centered care. There has been an increased recognition of the importance of PROMs generally, with concurrent emphasis on the patient experience as a fundamental component of quality of care. PROMs as defined by the FDA are “measurement[s] based on a report that comes directly from the patient about the status of a patient’s health condition without amendment or interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.” [ 12 ] PROMs are patient-generated and patient-centered health data, are measures of care delivery, evaluate patients’ symptoms, functional status, health related quality of life, satisfaction with care, and provide a holistic view of the patient experience [ 13 , 14 ]. While PROMs have traditionally been used as research tools, they are now recognized as meaningful clinical data elements, which may in certain instances be more accurate than those assessed by clinicians [ 15 , 16 ]. PROMs have been shown to support clinical improvements and positively impact patients in several fields [ 14 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ]. In addition, preliminary data has demonstrated that PROMs may have an overwhelmingly positive impact in gender-affirming surgery as well [ 22 ]. Moreover, the TGNB community desires high-quality, long-term outcome data [ 23 ]. PROMs are especially necessary in reconstructive surgery given the challenge in evaluating short and long-term outcomes and quality. Reconstructive surgery is a complex journey for a patient and is purely patient-driven; PROMs will ensure that this journey is patient- centered at each step including the initial consultation, decision-making process, surgery, and perhaps most importantly, outcome reporting and measurement.

While wide agreement for the need for PROMs in gender-affirming care exists [ 24 , 25 ], there are many challenges to their development and implementation [ 26 ]. Questions such as how data should be most effectively collected, visualized, shared, and used to improve quality have limited the routine use of PROMs in clinical care [ 21 ]. Surmounting these challenges begins by considering the benefit of PROMs at the patient, provider, and system levels [ 27 ]. At the patient level, PROMs can help patients undergoing genital gender-affirming surgery develop realistic expectations. In addition, PROMs provide an opportunity to understand patients’ priorities and enable them to become fully informed about benefits, risks, and available options much earlier in the process of seeking genital gender-affirming surgery. The routine collection of PROMs for patients undergoing genital gender-affirming surgery and their utilization in clinical practice can facilitate the provision of a roadmap for patients at each step on this journey. Ultimately, counseling with the use of PROMs can inform patients’ decision regarding whether to have surgery and which surgery to have (e.g., metoidioplasty vs. phalloplasty).

At the provider level, there is evidence that PROMs improve patient and physician satisfaction, increase workflow efficiency, and enable critical discussions [ 28 ]. PROMs help enhance both patient and provider satisfaction by helping physicians set appropriate expectations regarding patients’ outcomes. PROMs can also improve relationships and communication between physicians and patients as surgeons gain better understanding of patients’ priorities and desired outcomes from surgery [ 28 ]. The availability and utilization of PROMs may greatly influence the success of surgery and potentially avoid the need for revision surgery, which is beneficial to the patient and the provider. The success of surgery is highly dependent on an individual patient’s values and preferences; a physicians’ definition of success may be highly divergent from a patients’ definition. PROMs magnify the individuals’ voice and thereby emphasize and facilitate, for the provider, a patient- centered model of care. This patient-centered model of care, facilitated in part by PROMs, portends higher chances of success for the patient. It also gives the surgeon and team an opportunity to understand what is important to their patients. The use of a PROM tool in this context may be a segue to the development and use of tools to measure patient reported experience measures as well, which would further improve patients’ experience of gender-affirming surgery [ 29 ].

Finally, at the system level, one can use PROMs as a quality metric [ 26 ]. Distinct from clinical outcomes, PROMs can be used to measure structures, processes, and outcomes of health care and thereby, can improve quality of care at each step and in several ways [ 30 ]. PROM data can be used to evaluate variation in patient care—specifically, variation in the “best” outcomes from the patient’s perspectives and subsequently, areas for quality improvement. This can thereby lead to modified processes to improve outcomes and quality. PROMs focus on the effectiveness and experience of care, both of which are essential components of quality. Incorporating PROMs facilitates shared decision-making, which also improves quality of care. Additionally, PROMs have the unique ability to capture two additional major components of clinical care provision and quality—provider accountability and performance measurement. The potential of collaborative quality improvement among providers in this setting is vast. At the policy level, PROMs are fundamental for a transition from volume to value-based healthcare reform. Validated PROMs may also contribute to advocacy efforts for wider coverage and policies that serve transgender and non-binary patients. In this context, validation is important and refers to a PROM tool, which measures what it intends to measure in the target population [ 12 ]. PROMs have been and are currently used in genital gender-affirming surgery research, though they are not validated for use in transgender and non-binary populations nor are they specific for genital gender-affirming surgery [ 25 ].

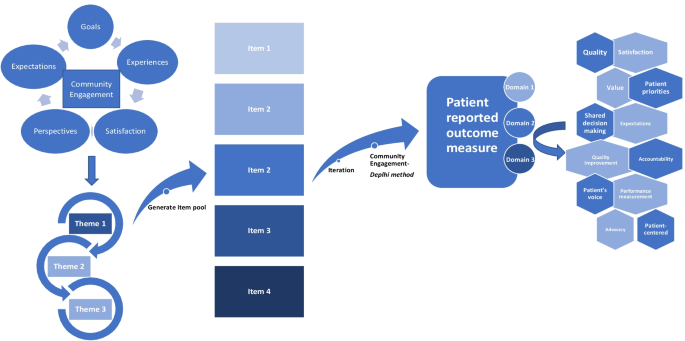

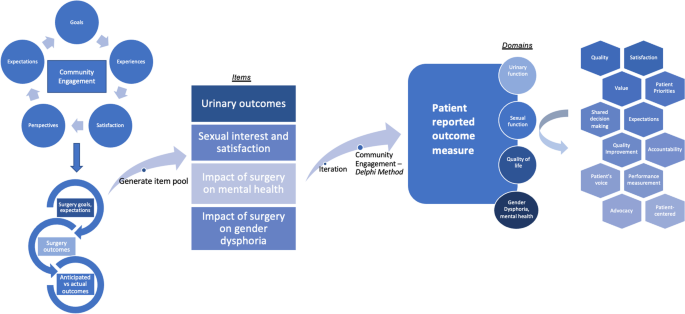

The primary role of PROMs is to capture the patients’ voice; given this, amplification of the patient’s voice at the forefront of PROM development is crucial. Figure 1 demonstrates a conceptual model for patient- engagement in PROM development; it is critical to have a conceptual framework to guide PRO measurement and assessment [ 31 ]. We plan to magnify the patients’ voices at each stage of development of PROMs for genital gender-affirming surgery. We propose early engagement with members of the transgender and non-binary communities in a Community-Based Participatory Research model. Engagement and collaboration with the TGNB community is fundamental in development of PROMs that are meaningful and relevant to the TGNB community and most importantly it will illuminate that which is often invisible—the patient perspective. Through engagement with LGBTQ community health centers, we are conducting focus group sessions for patients who will undergo or who have undergone phalloplasty, vaginoplasty, and metoidioplasty to gain a deep and detailed understanding of goals, experiences, quality of life, expectations, and aspirations. Qualitative analysis will then lead to convergent themes as depicted in Fig. 2 . Members of the transgender and non-binary community are leading or co-leading the focus group sessions. From initial discussions, dialogue, and thematic analysis, we will generate a pool of potential items for a PROM tool. This tool will then be rigorously vetted by the transgender and non-binary community members via a modified Delphi method, an iterative process whereby through data collection, analysis, and interpretation, the item pool is further modified with repeat in the cycle until there is agreement [ 32 ]. This enables and prioritizes PROMs that align with actual patient outcomes; this is divergent from the current outcome measurements, which prioritize surgical opinion. Only once agreement and homogeneity are reached amongst experts including TGNB focus group participants, TGNB community partners, qualitative researchers, and genital gender-affirming surgeons will decisions be made on items for the final tool, which would encompass domains (e.g., sexual, urinary, quality of life). This process will refine and finalize the tool which will then undergo rigorous validation testing. The final component of Figs. 1 and 2 depict the potential outcomes and areas of improvement from utilization of this PROM tool, including quality improvement, satisfaction, value, and shared decision making.

Patient-engaged conceptual model of patient reported outcome measure development

Potential themes, items, and domains resulting from community-based participatory research model of PROM tool development in genital gender-affirming surgery

PROMs for genital gender-affirming surgery are long overdue. Through intensive community engagement, we aim to develop PROMs with the transgender and non-binary community and inform the process of patient-centered care to serve transgender and non-binary patients. If surgeons who provide essential gender-affirming surgical care embrace the opportunity to be early adopters of PROMs, we can transform patient- centered care by making it a reality for transgender and non-binary patients.

Availability of data and materials