- Create a Timeline

History Of Philippine Art Timeline

This timeline presents the history of philippine art, including precolonial, spanish colonial, american colonial, and contemporary periods. discover the important artists, styles, and movements that have shaped the philippine art scene. more less, spanish colonial period, juan luna's "spoliarium" unveiled.

Juan Luna's "Spoliarium," unveiled in 1884, is one of the most iconic artworks in Philippine art history. This massive painting depicts the aftermath of gladiatorial combat during the Roman Empire, symbolizing the oppression and suffering endured by the Filipino people under Spanish colonial rule.

Image source: Juan Luna

Botong Francisco's "The Progress of Medicine in the Philippines"

Carlos "Botong" Francisco, a prominent Filipino muralist, completed "The Progress of Medicine in the Philippines" in 1953. This mural, located at the Philippine General Hospital, depicts the evolution of medical practices and the contributions of Filipino healers throughout history.

Image source: Botong Francisco

American Colonial Period

The thirteen moderns exhibition.

The Thirteen Moderns Exhibition, held in 1938, marked a significant turning point in Philippine art history. This exhibition showcased the works of thirteen Filipino artists who embraced modernist principles, challenging traditional artistic norms and paving the way for contemporary art in the Philippines.

Image source: Victorio Edades

Fernando Amorsolo's "The Burning of Manila"

Fernando Amorsolo, one of the Philippines' most renowned artists, painted "The Burning of Manila" in 1945. This powerful artwork depicts the destruction of Manila during World War II, capturing the devastation and resilience of the Filipino people.

Image source: Fernando Amorsolo

H.R. Ocampo's "Genesis"

H.R. Ocampo, a prominent modernist painter, created "Genesis" in 1950. This vibrant and abstract artwork reflects Ocampo's exploration of form, color, and movement, showcasing his significant contributions to Philippine modern art.

Contemporary Art

Art association of the philippines founded.

The Art Association of the Philippines was founded in 1948, becoming a vital organization in promoting and supporting contemporary Philippine art. It has played a significant role in fostering artistic development, organizing exhibitions, and providing platforms for artists to showcase their works.

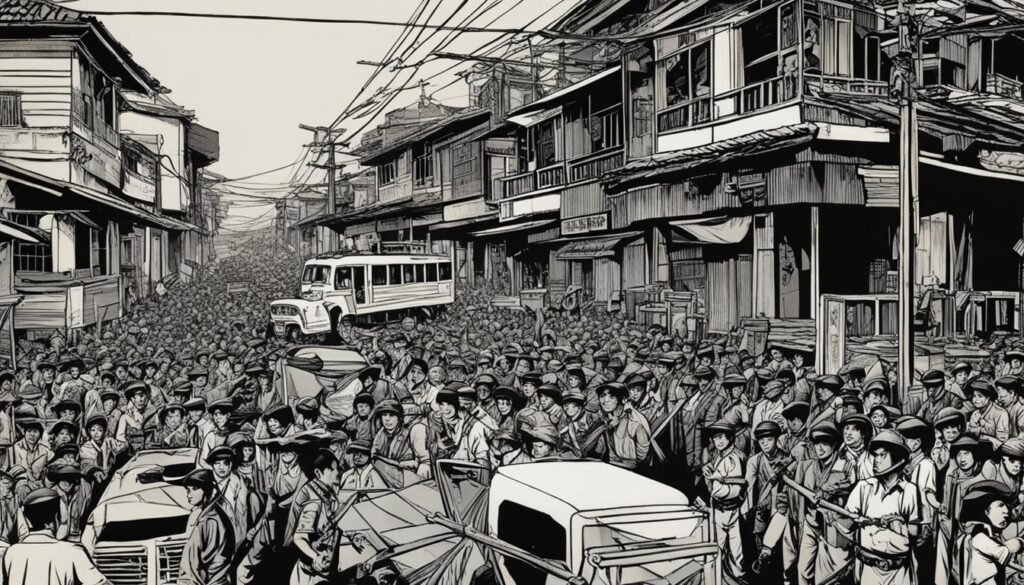

Vicente Manansala's "Jeepneys"

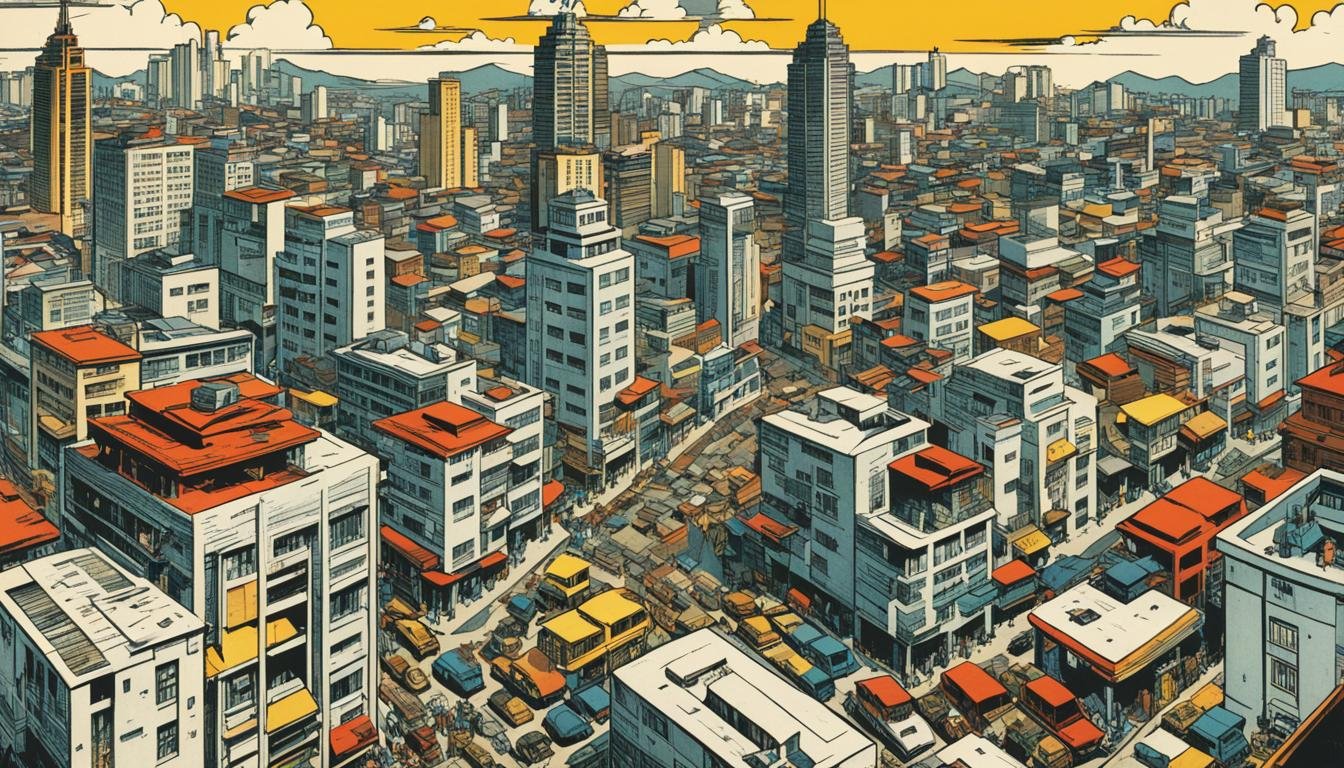

Vicente Manansala, a pioneer of Philippine modernism, painted "Jeepneys" in 1950. This iconic artwork captures the vibrant and colorful jeepneys, a popular mode of transportation in the Philippines, showcasing Manansala's unique style and portrayal of everyday Filipino life.

Image source: Vicente Manansala

BenCab's "Sabel" Series

Benedicto Cabrera, known as BenCab, began his iconic "Sabel" series in 1965. These paintings depict a stylized representation of a marginalized woman, symbolizing the struggles and resilience of the Filipino people. BenCab's "Sabel" series has become an important symbol of Philippine contemporary art.

Image source: Benedicto Cabrera

Imelda Marcos and the Cultural Center of the Philippines

Imelda Marcos, the former First Lady of the Philippines, played a significant role in the establishment of the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) in 1969. The CCP became a hub for various artistic disciplines, hosting performances, exhibitions, and fostering the development of Philippine arts and culture.

Image source: Imelda Marcos

Social Realism Movement Emerges

1970 - 1979

The 1970s saw the emergence of the Social Realism movement in Philippine art, characterized by artworks that reflect social issues, political commentary, and the struggles of the Filipino people. Artists like Nunelucio Alvarado, Antipas Delotavo, and Pablo Baen Santos played significant roles in this movement.

Image source: Social realism

National Artist Awards Established

The National Artist Awards were established in 1972 to recognize individuals who have made significant contributions to the development and enrichment of Philippine arts and culture. This prestigious award honors artists across various disciplines, including visual arts, literature, music, and more.

Image source: National Artist of the Philippines

Kidlat Tahimik's "Perfumed Nightmare"

Kidlat Tahimik's "Perfumed Nightmare," released in 1977, is a critically acclaimed independent film that explores themes of colonialism, identity, and the Filipino experience. This groundbreaking film marked a significant milestone in Philippine cinema and garnered international recognition.

Image source: Kidlat Tahimik

Art Fair Philippines Inaugural Edition

The inaugural edition of Art Fair Philippines took place in 2013, becoming a prominent platform for showcasing contemporary Philippine art. This annual event brings together local and international artists, galleries, collectors, and art enthusiasts, contributing to the growth and appreciation of Philippine art.

Image source: Zean Cabangis

Pre-colonial Art

Angono petroglyphs discovered.

The Angono Petroglyphs, discovered in 1965 in Rizal, Philippines, are ancient rock engravings that date back thousands of years. These prehistoric carvings depict various animals, human figures, and symbols, providing valuable insights into the artistic expressions of the early inhabitants of the Philippines.

Image source: Angono Petroglyphs

- Precolonial art in the Philippines includes pottery, goldsmithing, and weaving.

- The Spanish colonial period introduced Christianity and European art influences.

- Juan Luna and Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo, Filipino artists, gained international recognition in the late 19th century.

- The American colonial period brought modernism and the establishment of art schools in the Philippines.

- Contemporary Philippine art is characterized by experimentation and a reflection of social, political, and cultural issues.

This History Of Philippine Art timeline was generated with the help of AI using information found on the internet.

We strive to make these timelines as accurate as possible, but occasionally inaccurates slip in. If you notice anything amiss, let us know at [email protected] and we'll correct it for future visitors.

Create a timeline like this one for free

Preceden lets you create stunning timelines using AI or manually.

Customize your timeline with one of our low-cost paid plans

Export your timeline, add your own events, edit or remove AI-generated events, and much more

No credit card required.

Cancel anytime.

Common Questions

Can i cancel anytime.

Yes. You can cancel your subscription from your account page at anytime which will ensure you are not charged again. If you cancel you can still access your subscription for the full time period you paid for.

Will you send an annual renewal reminder?

Yes, we will email you a reminder prior to the annual renewal and will also email you a receipt.

Do you offer refunds?

Yes. You can email us within 15 days of any payment and we will issue you a full refund.

What if I have more questions?

Check out our pricing docs or send us an email anytime: [email protected] .

Download PDF

More options, download image.

- Subscribe Now

A one-stop resource on Philippine arts and culture is finally online

Already have Rappler+? Sign in to listen to groundbreaking journalism.

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

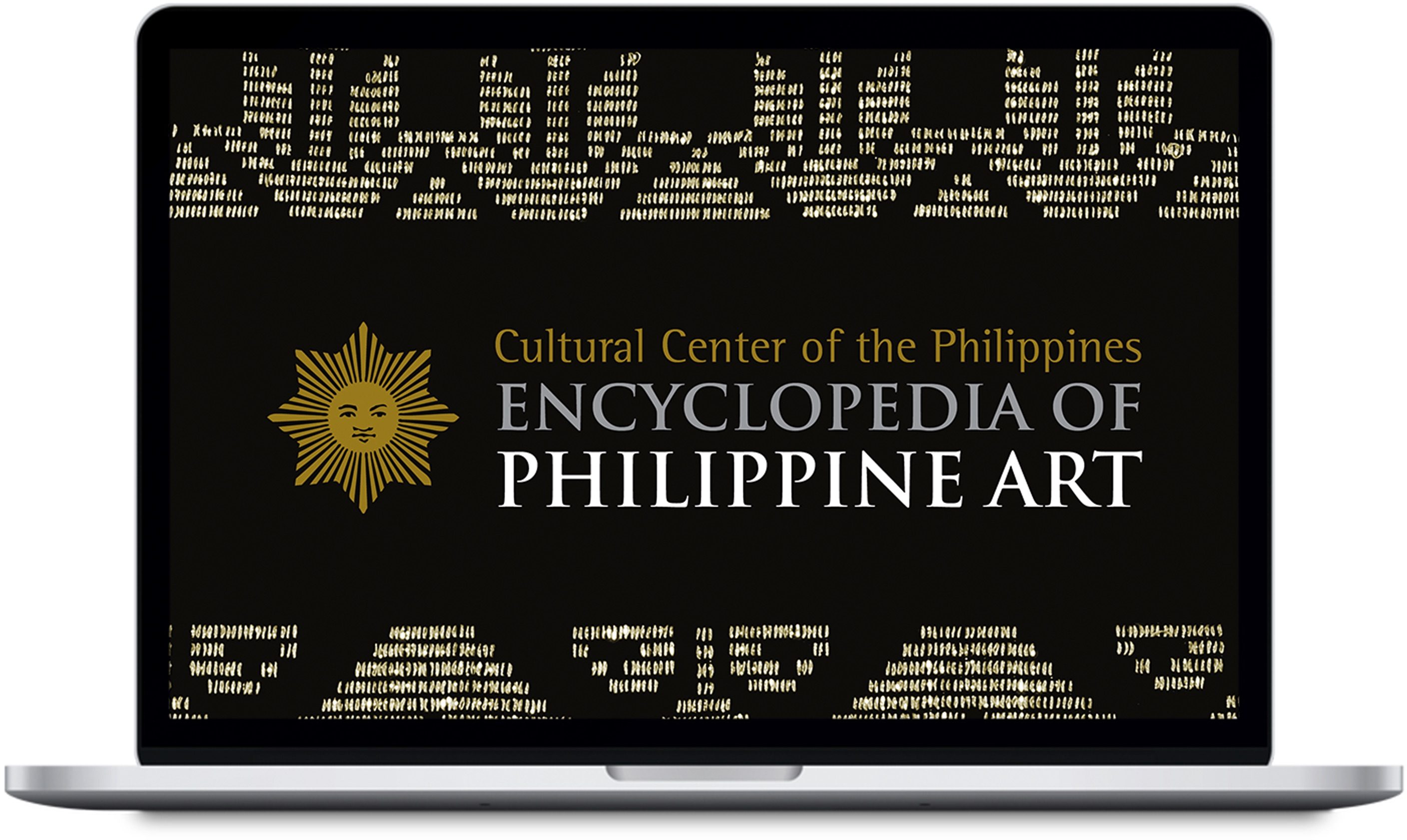

GOING DIGITAL. The Cultural Center of the Philippines launches the Digital Encyclopedia of Philippine Art

Photo courtesy of the Cultural Center of the Philippines

In 1994, the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) released the Encyclopedia of Philippine Art (EPA), a 12-volume set containing comprehensive information on Philippine architecture, visual art, film, music, and theatre, among many others

It was a promising project – giving people from all walks of life a one-stop resource for Philippine arts and culture. Nearly 3 decades later, the encyclopedia is finally available in digital form (known as the EPAD), making it more accessible to the public.

This updated version will come in three forms: a subscription-based website , an upcoming on-ground digital installation, and an offline version in flash drives.

How the encyclopedia started

The EPA project started out in the late 1980s as a brainchild of then-CCP artistic director Nicanor Tiongson, and was an answer to the growing need to collate our knowledge on Philippine arts and culture. Scholarly information on the subject was scattered across coffee table books, journals, and other special materials.

“There was a need for a resource on Phiippine arts and culture because it was virtually nonexistent,” says Chris Millado, the Vice President and Artistic Director of the CCP. “We wanted to enrich the curriculum and disseminate information.”

A large group of scholars and editors were consulted for the project, and over 300 writers contributed to the published body of work. Research encompassed various fields, including indigenous peoples, architecture, broadcast, visual art, film, music, dance and literature.

The first edition of the encyclopedia came out in 1994, and became a staple in libraries and resource centers.

“It helped promote the different histories that might have shaped our consciousness,” adds Chris. “The first edition was even found in universities abroad that offered Philippine Studies programs.”

The EPA includes entries on 54 ethnolinguistic groups in the country, from the Aetas to the Yakan. Other sections showcase information on Philipine architecture, visual art, film, music, dance, and literature.

“There’s this feeling when you read an entry and it’s about your hometown,” said Chris. “When you look at it, it develops a sense of pride for the places we hail from.”

Going digital

Work on the second edition of the encyclopedia started in 2013, nearly two decades after the first version was published. It was during this time that talks of a digital edition surfaced.

“We were already thinking of coming up with a digital edition even before the second edition came out,” said Chris. “Print encyclopedias are quite expensive and it was the time people were looking into digital formats.”

However, the suggestions to abandon the print format was met with resistance from the project’s team of researchers.

“Our researchers told us that we should go print first before going digital, because there is still a value in having a print edition,” said Chris. “After a back and forth between the editors, we agreed that a digital version will come first.”

The second edition was released in print in 2018, containing information updated up to 2015.

“The digital edition, in terms of content, will have at least a thousand new entries,” added Chris. “Digital makes it easier for us to edit and keep on updating. There are also no printing costs.”

The EPAD website contains 5,000 articles and 5,000 photos across nine sections. Videos from the vast archive of the CCP are also included in the EPAS. such as excerpts from plays and performances.

Besides articles on specific works, art forms, and traditions, the EPAD also has entries on Philippine personalities. Users can read up on historical figures like Jose Rizal and Juan Luna, or contemporary artists like Regine Velasquez and Sarah Geronimo.

A more portable learning resource

With the print edition being composed of twelve thick volumes, it is not exactly portable.

“You would have to get a large wheelbarrow just to move these around,” Chris joked. “In the digital version, you can access it on your mobile or tablet if you have wifi.”

The full set of the print version was available on the CCP website for Php 51,000. By contrast, the digital version is a subscription-based service with three tiers depending on the duration. A 1-month subscription is priced at Php75, while 6-month and 12-month subscriptions are available for P350 and P675, respectively.

Besides being more affordable and accessible, the encyclopedia also boasts features such as content bookmarking, auto-citation tools, and hyperlinking. Users may copy and paste portions of entries for research purposes, but a citation and copyright notice will be generated automatically. The site uses the 16th edition of The Chicago Manual of Style for citations.

“We value the intellectual property rights of the ones who own the images and wrote the essays,” said Chris. “But these features also make it easier to do citations, as opposed to writing them down.”

The bookmarking feature allows users to save content for later reading, and an “explore” tab allows for faster skimming and scanning. Users also have their own profile page, and a teams function is also available. Entries can also be easily shared by users through email, Facebook, and Twitter.

The interface is sleek and organized, and entries are easily searchable. The website also has a navigation guide, showing how the website categorizes its contents. Writers are also properly credited at the bottom of each entry.

The language used is very straightforward, and translations of localized terms are placed neatly in parentheses. Entries also have clear headings and subheadings, and key terms are typed in boldface. This makes the EPAD very easy to use, especially for students.

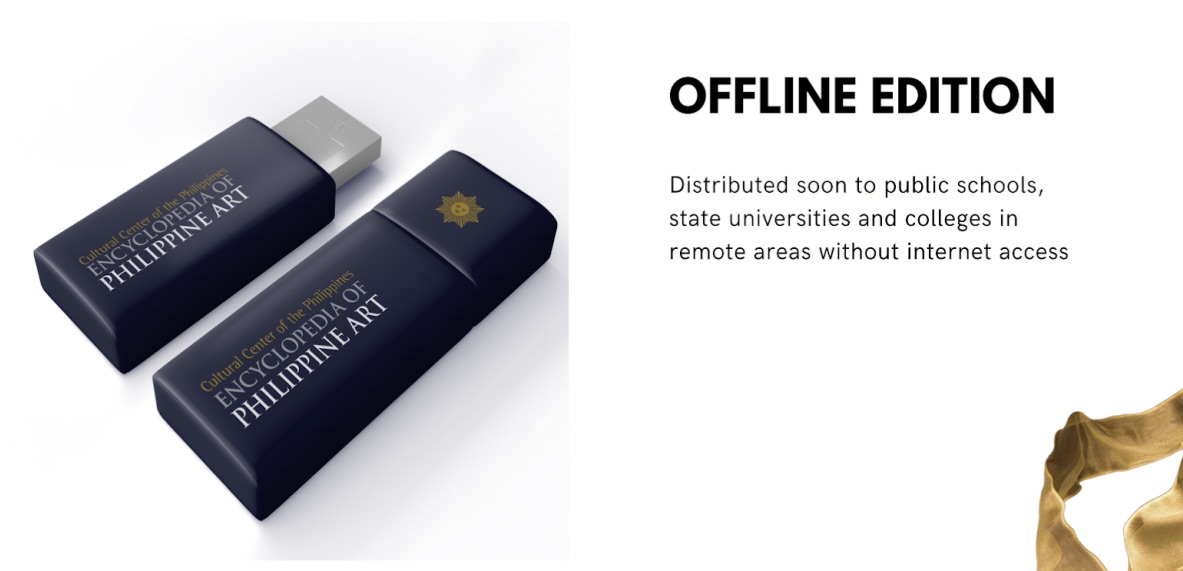

The EPAD project also has plans for an on-ground installation featuring a historical timeline, shown on eight 43-inch screens. A 12-volume PDF set placed in flash drives will also be available for offline access, aimed at those living in far flung areas.

The encyclopedia and the future of learning

While the EPAD has already launched, it will be updated with new entries twice a year. New features will also be rolled out periodically, as well as software and security updates.

“Even as we speak, we find out we need to keep updating,” said Chris. “There’s also the technical side of things, like security. We don’t want anyone hacking into it and changing entries.”

In spite of these, the release of the encyclopedia was not affected by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The shift of institutions to distance learning has made the project even more lucrative.

“The quarantine period made even more essential the use of online communication platforms for classroom learning,” said Chris. “Because of that, the digital version of the encyclopedia became even more relevant and necessary.”

Chris believes that the pandemic has changed the way learning is done, with online learning being used even after the pandemic is resolved.

“Even during the great pandemic lockdown, we continued with the work as scheduled,” he said. “Even after COVID, online platforms might remain as one of the primary ways for communication.”

“We’re offering something that might be in line with that,” he added.

The artistic director hopes that those who are enthusiastic about Philippine arts and culture will use the digital encyclopedia in their quest for knowledge.

“If you’re an institution or an individual, this digital version practically opens up a lot of portals for a deeper, broader, and wider understanding of our heritage.” – Rappler.com

Check out the EPAD here

Add a comment

Please abide by Rappler's commenting guidelines .

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.

How does this make you feel?

Related Topics

Recommended stories, {{ item.sitename }}, {{ item.title }}, filipino culture, meet tor sagud, the komikero champion of cordillera culture .

Palo, Leyte’s historic town, showcases rich gastronomy, culture

Wow Paraw Festival showcases Ilonggo boat-making skills, passion for the seas

[The Slingshot] No, no, no, National Museum! The Boljoon artifacts do not belong to you!

![timeline of philippine arts essay [The Slingshot] No, no, no, National Museum! The Boljoon artifacts do not belong to you!](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/tl-boljoon-artifacts-nat-museum-02242024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=270px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

[OPINION] Symbols of Pinoy greatness: The Philippines’ tallest statues

![timeline of philippine arts essay [OPINION] Symbols of Pinoy greatness: The Philippines’ tallest statues](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/the-victor-february-21-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=494px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

Checking your Rappler+ subscription...

Upgrade to Rappler+ for exclusive content and unlimited access.

Why is it important to subscribe? Learn more

You are subscribed to Rappler+

To print the story please do so via the link in the story toolbar.

PHILIPPINE ART HISTORY

this is a timeline where we will travel back in time to know more about our country's history in art.

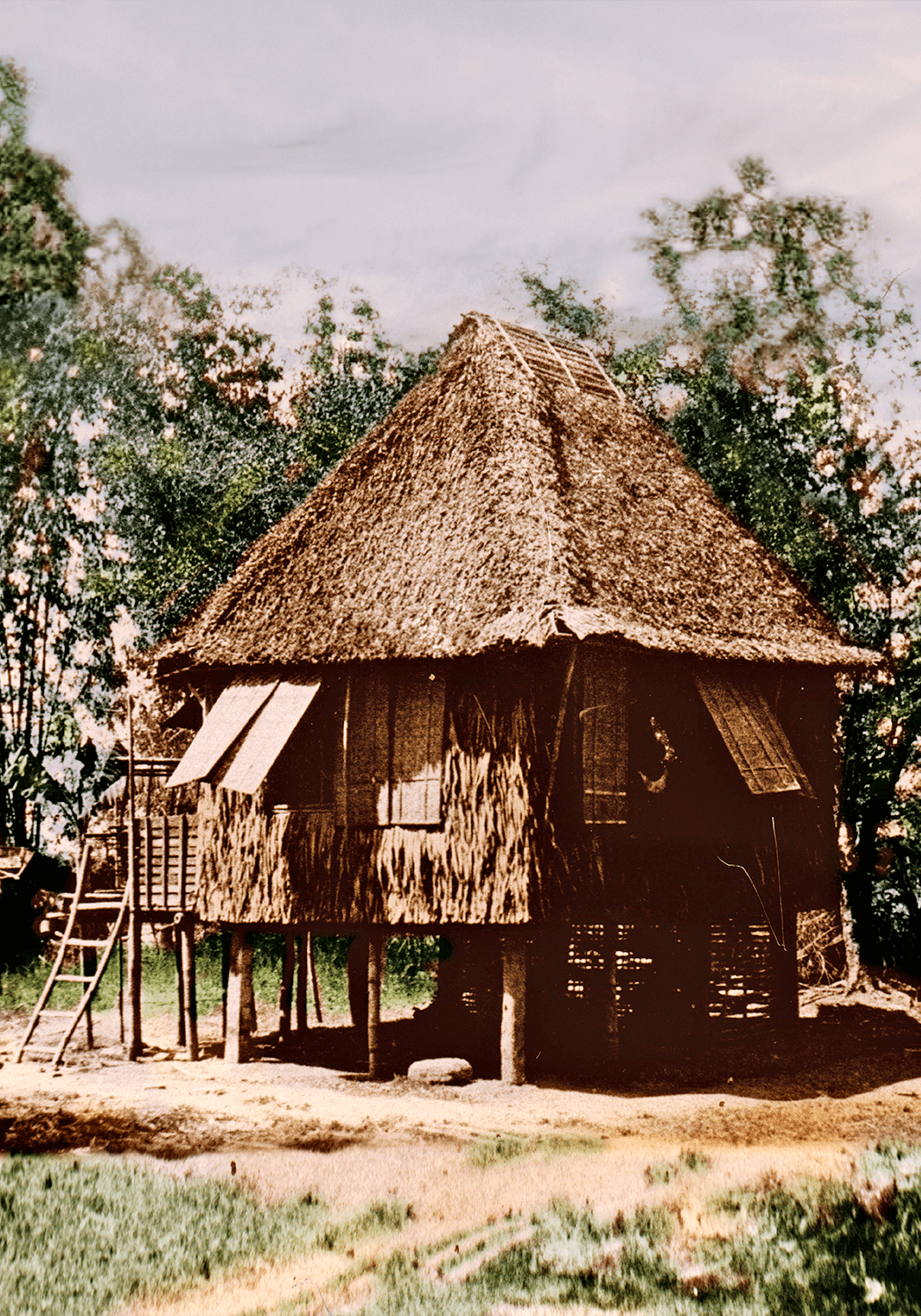

PRE COLONIAL PERIOD (Pre Conquest)

PRE-COLONIAL PERIOD

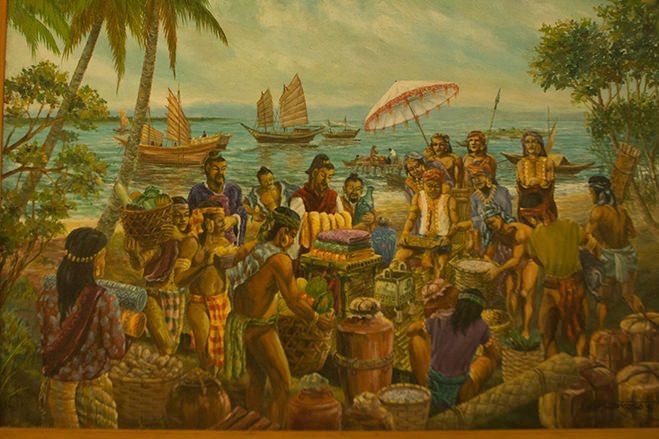

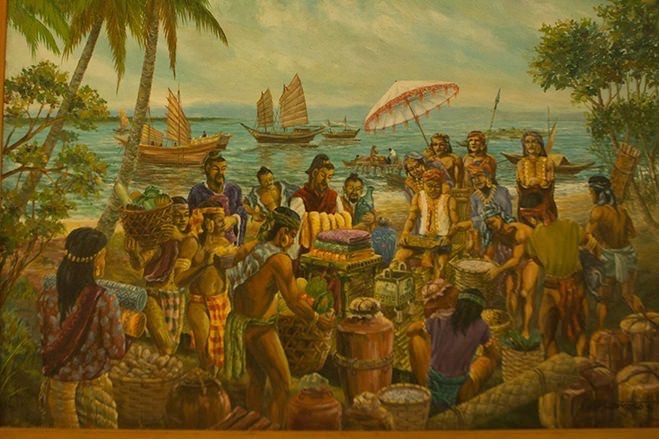

During pre-colonial time there was already indigenous spiritual tradition practiced by the people in the Philippines. Their practice were beliefs and cultural mores that the world is inhabited by spirits and supernatural entities.

Historians have found out that the "Barong Tagalog" already existed in this era. The earliest Baro or Baro ng Tagalog was worn by the natives of Ma-I (the Philippines name before).

Some worship specific dieties like Bathala (supreme God for tagalog), Idialao as God of farming, Lalaon as God of harvest, Balangay as God of rainbow. Others also worship the moon, star, mountains, plants and trees.

ISLAMIC COLONIAL PERIOD

In the 13th century, traders and missionaries have introduced the religon of Islam in the Philippines.

Is characterized by design of flowers, plant forms and geometric designs. It is used in calligraphy, architecture painting and other forms of fine art.

Mosques here in the Philippines have common architectural feature that is similar with Southeast Asian neighbors. Today's mosques are now structurally patterned after the design of its Middle Eastern counterparts.

During Pre-Colonial time there was already indigenous spiritual tradition practiced by the people in the Philippines.

Their practice was a collection of beliefs and cultural mores anchored by the idea that the world is inhabited by the spirits and supernatural entities.

Some worship specific dieties like Bathala, Idialao as God of farming, Lalaon as God of harvest, Balangay as God or rainbow. Others also worship moon, star, mountains, plants and trees.

Historians have found out that the "barong tagalog" already existed. The earliest baro o baro ng tagalog was worn by the natives of Ma-I (Philippines name before).

In the 13th century, traders and missionary have introduced the religion of Islam in the Philippines.

Islamic art is charcterized by the design of flower, plant forms and geometric design. It is used in calligraphy, architecuture painting, and other forms of fine art.

Mosques in the Philippines have common architectural features that is similar with its Southeast Asian Neighbors. Today's mosques are now structural patterned after the design of its Middle Eastern Counterpart.

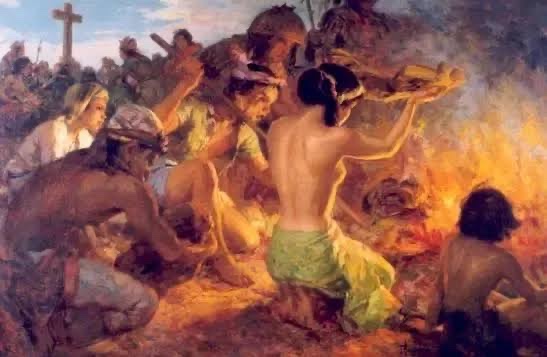

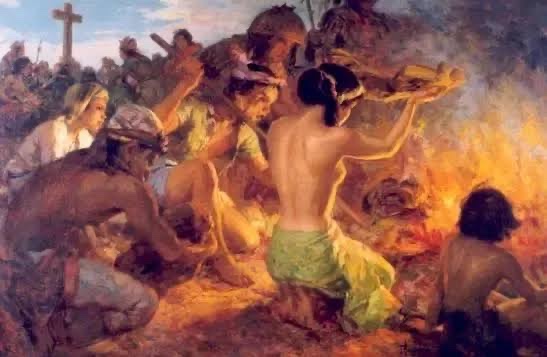

SPANISH COLONIAL PERIOD

First book to be printed in the Philippines, was a prayer book written in spanish with an accompanying Tagalog translation.

Spaniards ruled the country, brought the Christian religion and was responsible for a lot of colonial and religious buildings throughout the country.

Spaniards is the reason of mass baptism, it is the initial practice of baptizing large numbers of Filipino at one time.

AMERICAN OCCUPATION

Public schools were built and Thomasite teachers taught the American way of life.

Filipinos became dependent and sought out American Imported goods.

established civil government in the Philippines, is to train Filipinos in self government.

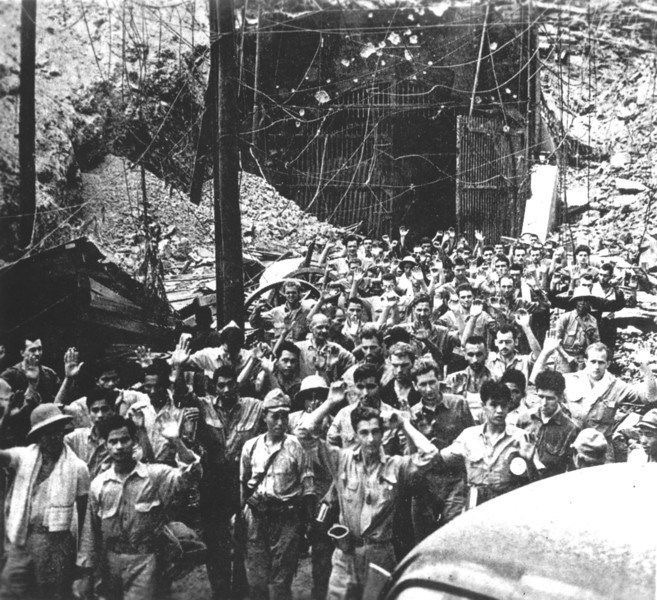

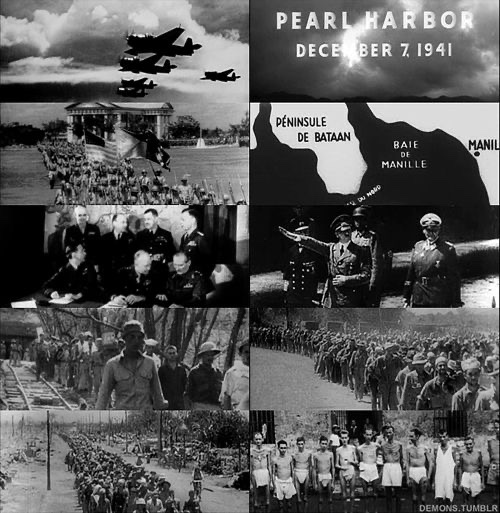

JAPANESE OCCUPATION

Japan attacks the Philippines. Manila was declared an open city.

10,000 prisoners of war were forced to march camps at Capas Tarlac.

Americans lost 60,628 men. Japanese lost 300,000 men. Filipinos lost 1 million men and women.

70's to Contemporary

an art by Ernest Concepcion-a filipino contemporary artist

Contemporary Philippine art is the art produced in the present period of time.

The art of the Philippines had been influenced by almost all spheres of the globe. It had the taste of Renaissance, Baroque and Modern Periods through the colonizers who arrived in the country.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

A Position Paper On The Future of Philippine Art

For us to conclude with what will happen to the future of Philippine art, we must first look back to its past, and critic its present.

Related Papers

Robyn Sloggett

access to global ideas and materials. Sixty-two oil paintings were examined and, unlike the works in the fi rst case study, were mainly secular in their subject matter. The majority of works are by artists connected to the University of the Philippines School of Fine Arts (UPSFA), then the art academy in the Philippines.3 According to Luciano Santiago, the early twentieth-century works in the JB Vargas Collection ‘reads like the who’s who in the history of art in the Philippines’4, and one could consider it to represent oil painting practice in the Philippines during this time frame. The key objective is to review the material evidence in view of the artistic discourses that informed each practice, whether they were Western, indigenous or Chinese in origin, or something other than these. The supply of materials and production processes in the Philippines is also another area of investigation that allows us to assess the material options available to artists and why certain products ...

Jereme Montoya

DAN RAFAEL SEBASTIAN

The research paper contains information related to Contemporary Philippine Arts from the Regions. It was a research work for the said subject.

Arnel Perez

Emerlyn Lincallo

Philippine Women's University

Barnuevo Marlon

In the Philippines, every professional and practicing Artist has his or her share of stories of encounters with people who seem to have little or no respect for their work and profession. This paper discusses the possible link between history and poverty, and the seemingly prevalent attitude of the Filipino masses towards artists, their work, and their industry. Special attention is given to discussing the possible relationship of Abraham Maslow's "Hierarchy of Needs", and the level of art appreciation of what is considered in this paper "the masses."

Kritika Kultura

Jovino Miroy

Interlaced Journeys: Diaspora and the Contemporary in Southeast Asian Art

Eva Bentcheva

This chapter examines different uses of the terms "artistic mobility" and "diaspora" through Philippine art history and recent curatorial practices. Interlaced Journeys: Diaspora and the Contemporary in Southeast Asian Art, Patrick D. Flores and Loredana Pazzini-Paracciani (eds.), Hong Kong: Osage Publications, 2020

Cha Gutierrez

The Spanish colonization of the Philippines from 1565 to 1898 brought about profound changes in the life and art of the Filipinos. Although some indigenous art forms survived, new forms and influences from Europe and America gradually became the dominant culture. When Spanish missionaries embarked on their campaign to Christianize the Filipinos, they harnessed the visual arts to great effect. Using the colorful pageantry of the Roman Catholic Church, the new evangelists so enchanted the natives that they had little difficulty winning them over and instructing them in the new faith. Religion was thereafter to provide such great impetus for the visual arts that in virtually every art form the sacred aspect became far more developed than the secular, thus continuing the intimate relationship between art and religion long established in ancient Filipino belief systems. However, while the colonizers were Spanish, a significant portion of artistic influences was not. The Chinese arrived in greater numbers from southeastern China to offer goods for the galleon trade and to sell services in the city of Manila. But there were periods when the Chinese would be expelled by the Spaniards from the colony in the mutual love-hate relationship between the two races. Filipinos benefited from this situation by mastering the Chinese skills so useful to the colonizers and practicing them when the Chinese were absent. With the galleon also came the Mexicans, whose cultural influence on the Filipinos, and vice versa, has until now received scant attention from scholars. Together, Portuguese, Italian, and even Bohemian priests evangelized with other missionaries. In the 19th century, English, French, American, German, and other nationalities also settled in Manila, further enriching the cultural milieu. Rituals and processions were the first visual aids. From the technologies used in crafting ritual paraphernalia developed the various visual art forms which characterized the Spanish colonial period: sculpture, painting, printmaking, furniture, fine metalwork, metal casting, textile arts, and fiesta decor. Sculpture Of all the arts, sculpture was the most familiar to the Filipinos. The carving of anito, images of the native religion, was replaced by the carving of santos, images of Christ and the saints. Technically, the transition may not have been too difficult, as the Filipinos were already familiar with the ways of wood, but adjustments had to be made on proportion and style. In time, santos took on the iconography of their Western prototypes.

RELATED PAPERS

International Journal of Energy Research

Saeed Tajik

Bianca Marrone

Baltic Forestry

Damjan Pantić

Antonia Maria Galera Rodriguez

Constructive Mathematical Analysis

Marco Baronti

Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy

Augusto Savi

Journal of High Energy Physics

Jonathan Shock

SHIRLEY ZURITA

Journal of Clinical Images & Reports

gosaye zewde

Neeme Tõnisson

Emilio CUETO

International Journal of Engineering

Rizal Firmansyah

Asian Journal of Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology

MALAY BHATTACHARYA

Environmental and Earth Sciences Research Journal

tugce ongen

Maria Esther Rambalde Santana

Satish Kumar

Stilistica E Metrica Italiana

Maria Sofia Lannutti

Psicologia & Sociedade

Roberta Romagnoli

Cardiologia Croatica

MARINA KLASAN

Sociological Practice

Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association

Rami Eleiba

Nicola Femminella sulla rivoluzione culturale di Menotti Lerro

Menotti Lerro

Tabuleiro De Letras

jean fisette

EdA Esempi di Architettura, International Journal of Architecture and Engineering Vol. 11 (no° 2), Jan. 26th: pp. 208-227.

Rana P.B. SINGH

Tạp chí Nghiên cứu Tài chính - Marketing

Sơn Trần Bảo

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

NEWS/COLUMN

Philippine Art: Contexts of the Contemporary

Patrick D Flores and Carlos Quijon, Jr.

Ginoe, Kabit Sabit All images courtesy of the artists and writers

The history of contemporary Philippine art traverses a vibrant terrain of artistic practices that delicately and urgently mediate the modernity of art history, institutions, exhibition-making, and the expansive activity of curatorial work. It performs this range of gestures to speak to and intervene in the ever-changing political milieu and the vast ecology, as well as ethnicity, of the archipelago. The Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP), which opened in September 1969, is an important institution in this history. The CCP was founded during the term of President Ferdinand Marcos, with the First Lady Imelda Marcos securing the funds for its construction and serving as its first chairperson. Its mandate was to promote national cultural expression and to “cultivate and enhance public interest in, and appreciation of, distinctive Philippine arts in various fields.” Other institutions of culture during this time were the Design Center of the Philippines (DCP), founded in 1973, the Museum of Philippine Art (MOPA), and the Metropolitan Museum of Manila (MET), the latter two instituted in 1976. The artist Arturo Luz concurrently directed these institutions, with his eponymous gallery practically managing the MOPA. The CCP was a venue for modern and international art and helped cultivate ideas of contemporary conceptualist and performance art. The practice of Raymundo Albano, curator of various spaces within the Center from 1970/1 until his death in 1985, is important in the development of curatorial discourse and practice in the Philippines. During his term, he conceptualized the idea of Developmental Art, which for him was a “powerful curatorial stance” inspired by “government projects for fast implementation.” Albano’s provocations inspired a rethinking of the nature of the art work: its form, cultural lineage, relationship with the audience, and ability to absorb the desire for distinction and identity. His initiative Art of the Regions, which presented the works of Junyee, Genera Banzon, and Santiago Bose is exemplary. Apart from these initiations, Albano also inaugurated the CCP Annual, a presentation of representative works of the year; and oversaw the publications Philippine Art Supplement, a bi-monthly art journal that ran from 1980 to 1982, and the three-issue magazine Marks, with Johnny Manahan. In 1981, Junyee organized the project Los Baños Siteworks. It was an exhibition held in a three-hectare “halfway ground between the mountain and the city.” For this platform, the region is imagined as a site and a sensibility away from the conventions of the typical gallery exhibition: “By utilizing nature’s raw materials as medium, the relationship between the art object and its surroundings are fused further into one cohesive whole.” The trope of region was a way of shifting the ecology of contemporary art exhibition, now “no longer confined within the boundary of gallery walls.” As Junyee describes the works in the exhibition: “Like extensions of nature, the works sprouted from the ground, floated in the air, surrounded an area, dangled from branches in random arrangement around the exhibition site.” Outside the Center, “social realism” developed in response to an increasingly authoritarian political milieu under the auspices of the developmentalist regime of Marcos. The term was explicated by critic Alice Guillermo who describes it as “not as a particular style but a commonly shared sociopolitical orientation which espouses the cause of society’s exploited and oppressed classes and their aspiration for change.” According to her, social realism was “rooted as it is in a commitment to social ideals within a dynamic conception of history, social realism in the visual arts grew out of the politicized Filipino consciousness.” The latter was forged by the Philippine revolution against Spain in 1896 and the continuing struggles against all oppressive systems. Guillermo argues that social realism in the Philippines “stresses the choice of contemporary subject matter drawn from the conditions and events of one’s time,” and “is essentially based on a keen awareness of conflict.” Whereas realism may be construed as a merely stylistic term, social realism is a “shared point of view which seeks to expose or lay bare the true conditions of Philippine society.” The work of the collective Kaisahan (Solidarity, 1975-6) whose members included painters Papo de Asis, Pablo Baen Santos, Orlando Castillo, Jose Cuaresma, Neil Doloricon, Edgar Talusan Fernandez, Charles Funk, Renato Habulan, Albert Jimenez, Al Manrique, Jose Tence Ruiz, and later joined by Vin Toledo, became emblematic of this tendency.

The quicksilver practice of the wunderkind David Medalla flourished during this milieu, albeit in an idiosyncratic vein. He was a homo ludens, provocateur, poet, and a prominent figure in modern and contemporary art in the Philippines and elsewhere who worked on kinetic, installative, participatory art, and other actions that do not neatly fall into accepted categories. During the opening of the CCP in 1969, he led a blitzkrieg demonstration that protested against what he saw as the Center’s philistinism. Caught by a cop securing the grand opening, Medalla was escorted outside, and when asked if he had the necessary permit to protest, he handed over his invitation, from the First Lady Imelda Marcos no less, and invoked his right to unfurl his art work—a cartolina on which was hand-painted: “A BAS LA MYSTIFICATION! DOWN WITH THE PHILISTINES!” The government of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos was deposed in 1986 by way of the EDSA People Power uprising. With the uprising came a renewed democratic impetus that skewed the priorities of institutions ensconced by the Marcoses. From being a venue for international travelling exhibitions, the MET focused on Filipino art. The CCP started to exhibit works of social realist artists, which could not be hosted in the 1970s. The DCP was absorbed by the Department of Trade and Industry. The administration of the MOPA was debated upon by organizations in a series of meetings revolving around the anxiety of what it takes for a post-Marcos institution to be democratic. In the end, it was discovered that the site of MOPA was not owned by the Philippine national government and that the institution itself did not have funds to continue its operations; ultimately, it was shuttered. The democratic impulse, alongside its myriad mystification from a resurgent pre-Marcos oligarchy, informed artistic practices and shaped ecologies of participation during this period. Artist collectives were formed as part of the renewed sense of democratized practice. Kababaihan sa Sining at Bagong Sibol na Kamalayan (Women in the Arts in an Emerging Consciousness, KASIBULAN) was founded in 1987 by visual artists Ida Bugayong, Julie Lluch Dalena, Imelda Cajipe Endaya, Brenda Fajardo, and Anna Fer. It was inspired by a consultation conference on Women Development organized by the National Commission on the Role of Filipino Women (NCRFW). At the heart of the organization was the goal to surface a “collective consciousness of Filipino women from which new image and identity can emerge and transformation can begin by giving a sense of power and empowerment” by creating “network[s] with women artists regionally, nationally, and internationally.” This collective consciousness presents itself in “her visual language, her sensibility, and artistic excellence” and in “symbolism, imagery, values, and beliefs of women’s personal and collective transformation” and in an interest in “crafts that are the traditional domain of women—tribal, indigenous, or folk, as an alternative effort to the inescapable influence of Western modernism.” Besides such aspiration, the group also endeavored to “assist women’s groups in resolving women issues that have long hindered the socio-economic and cultural growth of Filipino women.” The membership was “open to all women in the arts—visual, literary, and performing artists including art historians, educators, and critics who demonstrate a willingness to work for the sisterhood’s goals.” From monthly fora, to exhibitions, to publications, the KASIBULAN fostered a community of women artists, conscious of the issues of gender and the potentials of feminist struggle if the consciousness veered towards it. In the 1990s, discourses around regionality gained exceptional traction, especially with the help of CCP’s Outreach and Exchange Program and the establishment of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) in 1992. The NCCA was the “the overall policy making, coordinating, and grants giving agency for the preservation, development and promotion of Philippine arts and culture.” The mandate of the CCP’s Outreach and Exchange Program and NCCA ensured support for initiatives and projects outside Manila such as the Baguio Arts Festival (BAF), inaugurated in 1989, the Visayas Islands Visual Arts Exhibition and Conference (VIVA ExCon) founded in 1990, and the national travelling exhibition Sungdu-an (Confluence) that ran from 1996 to 2009. All three platforms convened artists from the regions and helped consolidate regional public spheres through exhibitions and meetings. The BAF, initiated by the Baguio Arts Guild, was instrumental in giving space for the arts and culture of the Cordillera region, north of Manila. The VIVA ExCon, helmed by members of the artistic collective Black Artists of Asia based in Negros Occidental, allowed for the cultivation of an inter-island connection among the provinces in the Visayas. Sungdu-an became an important step in the consideration of national art across archipelagic contexts through a curatorium based in the regions. Both VIVA ExCon and the Sungdu-an explored the potential of travelling as a method for artistic and curatorial practice in the Philippines and challenged notions of the “national” along axes of regions and the archipelagic condition. Today, the energy of artists, through their own volitions and the support of the market and the state, can be felt across the islands in the country, no longer confined to the center that is Manila, and freed from gospel of the prophets of international art. The belabored question of being Filipino has been displaced across the more productive notion of locality, one that is worldly and yet rooted. In many ways, the binary has been unmasked as a false choice and that the Philippine experience cannot sustain the premise. Alongside these more national considerations of region, international imaginaries of regionalisms also proliferated in the 1990s through exhibitionary and museological efforts. Important in this regard are the initiatives of the Asia Pacific Triennale (APT) organized by the Queensland Art Gallery in Brisbane that begun in 1993; the founding of the Singapore Art Museum (SAM) in 1996; and the pioneering collection and exhibitionary undertakings of the Fukuoka Art Museum (FAM) in Japan starting in 1979 and which became the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum (FAAM) in 1999. These three institutional initiatives offered a dynamic understanding of region-formation and regionality, prospecting the varied coordinates of the Asia-Pacific in APT, Southeast Asia in SAM, and Asia in FAM/FAAM.

Jocson, Princess Parade

The Fukuoka Art Museum pioneered in the exhibitionary efforts to present art from Asia. It inaugurated the Asian Art Show in 1979, one of the first exhibition platforms to present Asian art on a transregional scale. After the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum was established, the Asian Art Show transformed into the Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale which held its first edition in 1999. FAM also initiated the exhibition series Asian Art Today Fukuoka Annual featuring single-artist presentations, which included in its roster Roberto Feleo (Philippines, 1988), He Duo Ling (China, 1988), Tan Chinkuan (Malaysia, 1990), Tang Daw Wu (Singapore, 1991), Rasheed Araeen (Pakistan, 1993), Durva Mistry (India, 1994), Mokoh (Indonesia, 1995), Kim Young-Jin (South Korea, 1995), and Han Thi Pham (Vietnam, 1997). It also played an important role in the exhibition of art from Southeast Asia with exhibitions such as Tradition, Source of Inspiration (co-presented with the ASEAN Culture Center, 1990), New Art from Southeast Asia (1992), and Birth of Modern Art in Southeast Asia (1997). For its part, the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT) was the brainchild of the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art and was established in 1993. APT presented an exhibition, a film program, projects for children’s art, and a public program that gathered artists all over Asia for talks and workshops. Exceptional in APT’s trajectory was its focus on contemporary art from Asia, the Pacific, and Australia. Their programming was sustained by acquisition and commissioning of new works. It cultivated research and publication and actively offered residencies and training programs for artists and museum professionals in the Asia-Pacific region through the Australian Centre of Asia Pacific Art (ACAPA). Finally, the SAM came to the scene in 1996, guided by the acquisition, annotation, and exhibition of contemporary art from Southeast Asia. It helped condense a regional imagination of art in Southeast Asia and was influential in its historicization and discursive formation. Moreover, it forged the status of Singapore as an important location for regional contemporary art. While institutional projects thrived in the 1990s, the late 1990s and the early 2000s saw the proliferation of independent and artist-run spaces, presaging the horizontal, peer-to-peer scenarios in the years to come. These spaces threw sharp light on forms of gathering and participating in the artistic landscape poised to be different from, if not critical of, the scale and the economy of institutional programs. Earlier examples include Shop 6, founded by a group of artists led by artist and inaugural CCP curator Roberto Chabet in the 1970s, as well as The Pinaglabanan Art Galleries run by the artist Agnes Arellano and her partner British writer Michael Addams in the 1980s. These spaces were usually privately funded or existed with the support of private foundations. Some remarkable examples were Third Space, which was an exhibition and performance space founded by artist and filmmaker Yason Banal in Quezon City in 1998; Surrounded by Water in Angono, Rizal, put together by artist Wire Tuazon in the same year and which later became a collective of artists including Jonathan Ching, Mariano Ching, Lena Cobangbang, Louie Cordero, Cristina Dy, Eduardo Enriquez, Geraldine Javier, Keiye Miranda, Mike Muñoz, and Yasmin Sison; and big sky mind, conceived by artists Ringo Bunoan, Katya Guererro, and Riza Manalo in Manila in 1999. One of the longest-running alternative art spaces, Green Papaya Art Projects, emerged in 2000. Built up by artist Norberto Roldan (who was also one of the founding members of the collective Black Artists in Asia) and dancer and choreographer Donna Miranda, Green Papaya was “an independent initiative that supports and organizes actions and propositions that explore tactical approaches to the production, dissemination, research, and presentation of contemporary art in various and cross-disciplinary fields. It continues to provide a platform for intellectual exchange, sharing of information and resources, and artistic and practical collaborations among local and international artists and art communities.”

These histories shape the trajectory of contemporary Philippine art in the 2010s and onwards. With the development of exhibitionary discourses within institutions and beyond it through independent art spaces, the figure and agency of the curator signified the intelligence that became necessary in navigating the complex networks and economies these historical developments referenced. The curatorial agency was borne out of the self-reflexivity cultivated in ideas of contemporary artistic production and history within or against the discourses of the institutional, the independent, and the commercial. Crucial in this development was the Curatorial Development Workshops (CDW), a platform for curatorial education and training that was initiated by the Japan Foundation, Manila and the University of the Philippine Jorge B. Vargas Museum and Filipiniana Research Center in 2009. The CDW provided “a platform for interaction among young curators, their peers, and established practitioners in the field.” From an open call, a selection of emergent curators would be invited to present exhibition proposals in a workshop setting, with professional curators sharing about their practices and projects. The first iterations of the workshops gave one of the participants a chance to work as an intern curator in a Japanese institution under the JENESYS (Japan-East Asia Network of Exchange for Students and Youth) program and was given the space and guidance to realize their proposed exhibitions at the Vargas Museum. In 2017, the exhibition Almost There was held at the Vargas Museum alongside smaller scale exhibitions organized by chosen workshop participants across different venues in Southeast Asia. The 2010s also saw novel imaginations and platforms of exhibition-making and the making public of art. In 2013, the Art Fair Philippines was launched. It was a large-scale platform for exhibiting and selling modern and contemporary visual art in the Philippines and Southeast Asia. It also helped expand the audience for local visual art and, in its more recent iterations, helped push questions of accessibility and the publics of art. The career of artist Ronald Ventura is symptomatic of how artistic agency relates to the market, without necessarily being overwhelmed by its demands. Ventura’s works continue to mobilize more traditional techniques alongside a sensibility keen on spectacle and seriality. Ventura once held the record of the highest selling artist in Southeast Asia when his large canvas painting Grayground sold for more than 8 million HKD at the 2011 Sotheby’s auction. In May 2021, his work Party Animal sold at the Christie’s 20th and 21st Century Art Evening Sale for 19 million HKD, 16 times its estimate. This said, artists have set up their own spaces, with residency and mentorship programs, attuned to the vicinities and constituencies around them. And the primary and secondary markets have been hectic, evidenced in numerous fairs, auction houses, and galleries. In all this, the quality of Philippine contemporary art may be described as consistent across persuasions, whether it be realist painting or conceptualist installation, postcolonial intermedia or printmaking, or research-based projects linked to photography, moving image, sound, action, or archive. The year 2015 saw the participation of the Philippines at the Venice Art Biennale after more than 50 years. In 2015, Patrick D. Flores curated the exhibition Tie A String Around the World. The pavilion presented the works of National Artists Manuel Conde and Carlos Francisco and artists Jose Tence Ruiz and Manny Montelibano, probing technologies of conquest and worldmaking and their resonances in the contemporary contestations of territory in the South China Sea. The succeeding year also saw the participation of the Philippines in the Venice Architecture Biennale with the exhibition Muhon: Traces of an Adolescent City which looked at the architectural and urban history of Manila throughout the years curated by Leandro Locsin, Jr., Sudarshan Khadka, and JP dela Cruz.

Alongside these developments were equally compelling tendencies of practice that mediated contemporary contexts of production and reception of art and the potent possibilities in the areas of collaboration, intervention, and participation in artistic environments in the most expansive sense. The practice of Nathalie Dagmang has ventured into these considerations. As a student of anthropology and visual artist, she is interested in the interfacing of contemporary conditions of human experience, from ecological disaster-prone communities to the experiences of migrant workers, with the artistic process harnessed as a way to prompt conversations around social engagement. For her work Dito sa May Ilog ng Tumana (2016) she looks at the urban community of Baranggay Tumana that is situated along the Marikina river. In her ethnographic project, she investigates how the relationship between the site and the community becomes mutually transformative: the residential settlements continuously change the topography of the river, and the river becomes inextricable with how daily life is imagined both as quotidian landscape and as a site in constant risk of inundation due to tropical typhoons. Dagmang also took part in “Curating Development,” a program based in the United Kingdom and funded by the Asian Human Rights Commission. Working with curators and anthropologists, she initiated workshops and community-based art activities with the Filipino migrant workers based in the United Kingdom and Hong Kong and conceived exhibitions that looked at the contributions of migrant labor to the Philippine imagination. The cogent relations between activism and performance are fleshed out in the practice of Boyet de Mesa, who also convenes the annual Solidarity In Performance Art Festival (SIPAF), an artist-organized project that promotes cultural exchange, solidarity, and peace through performance festivals that started in 2015. Artist Eisa Jocson’s practice discerns this same interventive potential in performance in her works that look at feminized and queer migrant labor, such as in the work Princess Studies (2017-) and The Filipino Superwoman Band (2019), with Franchesca Casauay, Bunny Cadag, Cath Go, and Teresa Barrozo. This performative agency likewise inspires the practice of artist and architect Isola Tong whose works interrogate urban space and development and notions of wildlife within the framework of transgender politics and ecosystems. Finally, it is through performance that the romanticization of the diasporic experience is refused without disavowing its intimacies and prospects: the practice of Noel de Leon who is based in London and co-directs Batubalani Art Projects takes interest in how objects survive and index traces of historical conflicts and circulations of both people and things. Meanwhile, the practice of Lilibeth Cuenca Rasmussen who is based in Copenhagen devises performances that propose simultaneously ludic and critical ways of struggling with the tenacious demands of “identity” and “culture” and their situatedness and displacements. This keenness on the options in participation and more horizontal logics of practice finds exceptional articulation in Load na Dito, a mobile research and artistic project founded in 2016 by artist Mark Salvatus and curator Mayumi Hirano. It foregrounds the critical and creative possibilities that inhere in collective and interactive action of making, presenting, and curating art. In 2019, Load na Dito proposed Kabit at Sabit , a multi-modal and multi-site exhibition that involved practitioners from all over the archipelago. From the Filipino words for connect or install and inspired by the Pahiyas Festival in Lucban, Quezon, the hometown of Salvatus, the curatorial project invited practitioners to create artistic projects that investigated installation as a technology of display. Each practitioner was asked to choose a façade in which they attached or installed objects, transforming the site into an exhibitionary space where art meets its public—both incidental and intentional. In these tendencies and trajectories of practice and institutional history, Philippine contemporary art demonstrates an acute discernment of persistent and current concerns, one that shapes the lively intellects of engaged artists and continually expands the effects of their intuitions.

Abuga-a, Kabit Sabit

Quinto, Kabit Sabit

About the Writers

Patrick D Flores is Professor of Art Studies at the Department of Art Studies at the University of the Philippines and Curator of the Vargas Museum in Manila. He is the Director of the Philippine Contemporary Art Network. He was one of the curators of Under Construction: New Dimensions of Asian Art in 2001-2003 and the Gwangju Biennale (Position Papers) in 2008. He was a Visiting Fellow at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. in 1999. Among his publications are Painting History: Revisions in Philippine Colonial Art (1999); Past Peripheral: Curation in Southeast Asia (2008); Art After War: 1948-1969 (2015); and Raymundo Albano: Texts (2017). He was a Guest Scholar of the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles in 2014. He was the Artistic Director of Singapore Biennale 2019 and is the Curator of the Taiwan Pavilion for Venice Biennale in 2022.

Patrick D Flores

Carlos Quijon, Jr. is a critic and curator based in Manila. He is a fellow of the research platform Modern Art Histories in and across Africa, South and Southeast Asia (MAHASSA), convened by the Getty Foundation’s Connecting Art Histories project. He writes exhibition reviews for Artforum and Frieze. His essays are part of the books Writing Presently (Philippine Contemporary Art Network, 2019) and From a History of Exhibitions Towards a Future of Exhibition-Making (Sternberg Press, 2019). He has published in MoMA’s post (US), Queer Southeast Asia, ArtReview Asia (Singapore), Art Monthly (UK), Asia Art Archive's Ideas (HK), and Trans Asia Photography Review (US), among others. He curated Courses of Action in Hong Kong in 2019, co-curated Minor Infelicities in Seoul in 2020, and In Our Best Interests: Afro-Southeast Asia Affinities during a Cold War in Singapore in 2021.

Carlos Quijon, Jr.

Searching for the Self-Re-Identities: Brief Introduction of Taiwanese Contemporary Arts, and Its Connection with Southeast Asia

Thai Contemporary Art -Past and Present-

Overview: History of Contemporary Art in Lao PDR

Overview: History of Contemporary Art in Myanmar

Overview: History of Contemporary Art in Cambodia

Overview: History of Contemporary Art in Thailand

Filipinas Kong Mahal

- Post-War Era and Third Republic (1946-1972)

The Philippine Literature and Arts in the Post-War Era (1946-1972)

by Historian · 21 January 2024

The post-war era from 1946 to 1972 in the Philippines was a transformative period for Philippine literature and arts . It witnessed the emergence of different genres, themes, and styles in Philippine literature and the arts scene. This period showcased the evolution of Philippine cultural expression and the influence of historical events on artistic works.

Key Takeaways:

- The post-war era in the Philippines (1946-1972) marked a significant transformation for Philippine literature and arts .

- The period saw the emergence of different genres , themes , and styles in Philippine literature and the arts scene.

- Philippine cultural expression evolved during this time, influenced by historical events.

- The post-war period left a lasting impact on Philippine literature and arts, shaping the cultural landscape and the national identity.

Evolution of Philippine Art Forms and Styles

In the post-war era , Philippine art witnessed the development of various art forms and styles , influenced by the socio-cultural context of different historical periods . The evolution of Philippine art can be categorized into distinct periods that shaped the artistic landscape of the country.

Pre-Colonial Art Period

The Pre-Colonial Art Period encompassed the art forms and styles that existed before the arrival of European colonizers. During this period, indigenous communities in the Philippines showcased their artistic talent through various mediums such as sculpture, pottery, weaving, and tattooing. Artworks during this period often reflected the spirituality, social structure, and everyday life of these communities.

Spanish Colonial Art Period

With the arrival of the Spanish colonizers, Philippine art experienced significant changes. Spanish influence introduced new art forms such as painting, sculpture, and architecture. Religious themes dominated the artworks of this period, reflecting the fusion of Spanish Catholicism and local indigenous beliefs. Baroque and Rococo styles had a profound impact on Philippine art, evident in the intricate details and lavish ornamentation of religious sculptures and colonial churches.

American Colonial Art Period

The American Colonial Art Period brought modernity and Western influences to Philippine art. Academic art styles , including Realism and Impressionism, gained popularity among Filipino artists who studied abroad. This period witnessed a shift towards more secular and nationalist themes , reflecting the aspirations and struggles of the Filipino people under American rule. Artists like Fernando Amorsolo became prominent figures during this period, known for their depictions of rural scenes and landscapes.

Post-War Colonial Art Period

The Post-War Colonial Art Period was marked by the aftermath of World War II and the restoration of independence in the Philippines. Artists sought to find a distinct Filipino identity in their art, often combining traditional elements with modernist and abstract styles. This period witnessed the emergence of social realism as artists depicted the struggles, poverty, and inequality faced by Filipino society.

Contemporary Art Period

The Contemporary Art Period showcases the diversity, experimentation, and global influences in Philippine art today. Filipino artists explore various mediums, styles, and techniques, reflecting the dynamic and rapidly changing nature of contemporary society. Contemporary Philippine art encompasses various art forms, including painting, sculpture, installation, performance art, digital art, and mixed media.

“Each period in Philippine art history has contributed to the rich tapestry of cultural expression in the country. The evolution of art forms and styles reflects the continuous exploration of identity, traditions, and the ever-changing socio-political landscape of the Philippines.” –Art Historian

To gain a deeper understanding of Philippine art, it is essential to appreciate the diverse art forms and styles that have emerged throughout history. The following table provides a summary of the key periods and their corresponding art forms and styles:

Aesthetics and Its Significance in Philippine Art

Aesthetics , a branch of philosophy that examines the principles of beauty and artistic taste, plays a crucial role in understanding and appreciating the nature of Philippine art. The concept of aesthetics helps define what makes an artwork distinctly Filipino and explores the connections between Philippine contemporary art and its origins in the world.

Philippine art, with its rich cultural heritage and diverse influences, embodies the aesthetic sensibilities of the Filipino people. From the intricate wood carvings of indigenous tribes to the vibrant paintings of modern Filipino artists, aesthetics permeates every aspect of the artistic expression in the country. It is through aesthetics that we can delve into the deeper meanings and narratives embedded within these art forms.

“Art enables us to find ourselves and lose ourselves at the same time.” – Thomas Merton

Art appreciation is closely tied to aesthetics, allowing individuals to engage with and interpret artworks on a personal level. By examining the various elements of an artwork – its composition, color palette, symbolism, and emotional impact – we can better understand the intentions and messages conveyed by the artist.

Through the lens of aesthetics, we can embark on a journey of discovering the beauty and complexity of Philippine art. Whether it’s the harmonious blend of indigenous and foreign influences, the exploration of social issues, or the celebration of Filipino identity, aesthetics guides us in unraveling the artistic tapestry of the Philippines.

Key Elements of Aesthetics in Philippine Art

The beauty and significance of Philippine art lie in its ability to captivate, challenge, and inspire. By embracing aesthetics and delving into art appreciation , we deepen our understanding of the unique cultural heritage and artistic expressions of the Filipino people.

Development of Philippine Art from Pre-Colonial to Contemporary Periods

The development of Philippine art spans across different historical periods , each contributing to the rich and diverse artistic heritage of the country. These periods include the Age of Horticulture/Neolithic Period, Metal Age, and Iron Age, which marked significant shifts in artistic expression and cultural development.

During the Age of Horticulture/Neolithic Period, which lasted from around 2000 BCE to 1000 BCE, the early inhabitants of the Philippine archipelago began to settle in communities and engage in agricultural practices. This period witnessed the emergence of pottery-making and the creation of intricate ceramic vessels adorned with various designs and motifs. The art of this period often incorporated elements of nature, reflecting the people’s deep connection to the environment.

Transitioning to the Metal Age, which occurred from around 1000 BCE to 1521 CE, the introduction of metalworking techniques revolutionized artistic practices in the Philippines. The mastery of metalworking skills allowed artisans to create intricate jewelry, weapons, and ceremonial objects. This period also saw the rise of goldwork, with intricate gold jewelry and ornaments showcasing the exceptional craftsmanship of early Filipino artisans.

Art of the Pre-Colonial Period

“The art of the pre-colonial period in the Philippines is a testament to the rich cultural heritage and artistic prowess of the early Filipino people.” – National Museum of the Philippines

The pre-colonial period, spanning from around the 10th century to the arrival of Spanish colonizers in the 16th century, witnessed the peak of indigenous artistic expression in the Philippines. Art during this time encompassed a wide range of mediums, including sculpture, pottery, textiles, and architectural design.

Religious symbols played a significant role in pre-colonial Philippine art, with sculptures and carvings depicting deities, ancestors, and mythical creatures. These works of art served both aesthetic and spiritual purposes, embodying the beliefs and rituals of the indigenous communities. Furthermore, everyday activities and natural elements were often depicted in art, reflecting the close connection between the people and their environment.

Pre-colonial Philippine art also showcased decorative art patterns influenced by both local and foreign sources. Intricate geometric designs, intricate weaves, and vibrant colors adorned various textiles, pottery vessels, and architectural elements. These patterns not only added beauty to the objects but also conveyed meanings and stories specific to each community.

In summary, the development of Philippine art from pre-colonial to contemporary periods reflects the profound cultural heritage and artistic creativity of the Filipino people. Each historical period contributed to the evolution and diversification of art forms, from the Age of Horticulture to the Metal Age, and finally, the exceptional art of the pre-colonial period. These artistic traditions continue to inspire and influence contemporary Philippine art, fueling the vibrant and dynamic artistic landscape of the country.

Okir Motif and Its Cultural Heritage

The Okir motif is a distinctive artistic design that holds significant cultural heritage for the Maranao people of Lanao, Philippines. Originating from the early 6th century, before the Islamization of the region, the Okir motif is a testament to the rich artistic traditions and craftsmanship of the Maranao community.

The Okir motif is characterized by its elegant curvilinear lines, intricate wood carvings, and the integration of Arabic geometric figures. These distinctive features come together to create a visually captivating and culturally significant art form. The motifs include elements such as Matilak (circle), Poyok (bud), Dapal (leaf), Pako (fern), and Todi (fern leaf with a spiral), each symbolizing different aspects of nature and spirituality.

Maranao art , with its Okir motif, represents the creative expression and artistic legacy of the Maranao people. It serves as a visual representation of their cultural identity, reflecting their deep connection to nature, religion, and traditional beliefs. The intricate wood carvings and elaborate designs showcase the meticulous craftsmanship passed down through generations, preserving their unique cultural heritage.

The Okir motif is not just a stunning artistic creation; it is a testament to the resilience and creativity of the Maranao people. It serves as a bridge between the past and the present, reminding us of the enduring beauty and cultural richness that should be celebrated and preserved. — Dr. Maria Escano, Cultural Historian

Significance in Philippine Art

The Okir motif holds a special place in Philippine art due to its historical and cultural significance. It represents a fusion of indigenous artistic traditions with external influences, creating a unique art form that is distinctly Filipino. The intricate carvings and attention to detail in Okir motifs exemplify the skill and artistry of Filipino craftsmen.

Furthermore, the Okir motif serves as a visual link to the pre-Islamic cultural heritage of the Maranao people. It showcases the artistic traditions and craftsmanship that have been passed down through generations, reflecting the enduring cultural identity of the Maranao community.

Preserving Cultural Heritage

Preserving and promoting the Okir motif is crucial for the continued celebration of Maranao art and cultural heritage. Efforts are being made to document, conserve, and pass on the knowledge and skills associated with the Okir motif to future generations.

Organizations such as the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) and local cultural agencies work hand in hand with Maranao artists and craftsmen to ensure the preservation and promotion of the Okir motif. Exhibitions, workshops, and cultural exchanges are organized to raise awareness about the significance of this art form and to encourage its continued practice.

The Cultural Legacy of the Okir Motif

The Okir motif stands as a testament to the rich cultural heritage of the Maranao people and their contribution to Philippine art. It represents a harmonious blend of indigenous artistic traditions and external influences, showcasing the creativity and craftsmanship of the Maranao community.

This intricate art form serves as a reminder of the importance of preserving cultural heritage and celebrating the diversity of Philippine art. By understanding and appreciating the Okir motif, we gain a deeper appreciation for the artistic traditions and cultural identities that make the Philippines a vibrant and culturally diverse nation.

Influence of Spanish Colonialism on Philippine Art

The Spanish colonial period had a profound impact on Philippine art, introducing formal painting, sculpture, and architecture to the archipelago. Spanish art styles from various periods such as Byzantine, Gothic, Baroque, and Rococo heavily influenced the development of Philippine art aesthetics . This fusion of Spanish and local influences resulted in unique art forms and styles that showcased the rich cultural heritage of the Philippines.

During the Spanish colonial era, religious themes dominated Philippine art, as the Church played a central role in society. Artists often depicted biblical scenes, saints, and Christian iconography in their works. These religious themes intertwined with indigenous beliefs and customs, creating a distinct artistic expression that reflected the fusion of Spanish and Philippine cultures.

“The Spanish colonial period not only introduced new art forms to the Philippines but also provided a platform for the convergence of different cultural influences. The resulting artworks exemplify the complexity and richness of Philippine art aesthetics .”

Spanish architectural styles, such as the Baroque and Rococo, influenced the construction of churches, cathedrals, and colonial buildings in the Philippines. Intricate details, ornamental designs, and grandeur characterized these architectural marvels, revealing the Spanish colonial imprint on the landscape.

Spanish Colonial Art in the Philippines

Spanish colonialism left a lasting impact on Philippine art, shaping its aesthetics and introducing new artistic techniques. The influence of Spanish art styles can still be observed in contemporary Filipino artworks, showcasing the enduring legacy of the Spanish colonial period.

Literary Landscape in the Post-War Period

The post-war period in the Philippines showcased a vibrant literary landscape, characterized by the exploration of various themes and genres . Writers in this era delved into the effects of the war and the challenges faced during the post-war period, creating literary works that reflected social issues and personal struggles.

Notable writers emerged during this time, contributing to the rich tapestry of Philippine literature. Some of the prominent figures include:

- NVM Gonzales, known for his short stories that captured the nuances of Filipino society.

- Nick Joaquin, an iconic Filipino writer whose works spanned various genres , including fiction, plays, and essays.

- F. Sionil Jose, a prolific author whose novels explored themes of social inequality and political unrest.

These writers , along with many others, played a crucial role in shaping the literary landscape of the post-war era. Their works not only provided insights into the social and political circumstances of the time but also showcased the talent and creativity of Filipino writers.

“Literature is essential in capturing the essence and spirit of a nation. It serves as a mirror that reflects the triumphs, struggles, and aspirations of a people.” – NVM Gonzales

Prominent Literary Movements

During the post-war period, several literary movements emerged, each with its unique characteristics and contributions. These movements helped define and shape Philippine literature, further enriching its diversity and depth. Some of the notable literary movements include:

These literary movements provided platforms for writers to explore diverse themes and push the boundaries of traditional storytelling, contributing to the dynamic landscape of post-war Philippine literature .

The post-war period in Philippine literature was a time of exploration, creativity, and resilience. Writers engaged with their socio-political reality, producing literary works that continue to resonate with readers today. Through their words, these writers have left an indelible mark on the literary heritage of the Philippines.

Literary Movements and Themes in Post-War Philippine Literature

Post-war Philippine literature witnessed the emergence of various literary movements and themes that reflected the societal changes and challenges of the time. These movements and themes played a crucial role in shaping the direction and content of Philippine literature in the post-war era.

Realism was an important literary movement in post-war Philippine literature . It focused on depicting ordinary life and social issues, providing a realistic portrayal of the Philippine society and its struggles. Realist writers sought to bridge the gap between literature and everyday experiences, presenting stories that resonated with readers on a personal level. By highlighting the harsh realities and social conditions, realism aimed to bring about social awareness and change.

Social Realism

Social realism emerged as a response to the exploitation and injustices prevalent in post-war Philippine society. Writers under this movement aimed to expose the social issues, including poverty, inequality, and corruption, through their works. They sought to emphasize the plight of the marginalized and bring attention to the systemic problems that hindered progress and development. Social realism in Philippine literature became a platform for social critique and a call for social transformation.

The modernist literary movement in post-war Philippine literature marked a departure from traditional forms and explored new avenues of expression. Modernist writers experimented with language, narrative structures, and unconventional storytelling techniques. They challenged established norms and pushed the boundaries of literary conventions. Modernism in Philippine literature sought to capture the changing times and the evolving Filipino identity in a period of rapid modernization.

The themes in post-war Philippine literature were diverse and reflected the multiple facets of the Philippine experience during that time. Many works addressed the quest for national identity and explored the complexities of being Filipino in the aftermath of war and colonialism. Other prevalent themes included social inequality, political unrest, cultural identity, and the search for personal liberation. These themes allowed writers to engage with the pressing issues of the society and provide insights into the Filipino psyche.

“Literary movements and themes in post-war Philippine literature provided a lens through which writers could reflect the realities of society and explore the complexities of the Filipino experience. By capturing the spirit of the times and addressing pressing issues, these movements and themes continue to resonate with readers and offer valuable insights into the post-war era.”

In the next section, we will explore notable works and writers in post-war Philippine literature, highlighting their contributions to the literary landscape and their enduring impact on Filipino culture.

Notable Works and Writers in Post-War Philippine Literature

The post-war period in the Philippines witnessed the emergence of numerous notable works and talented writers in Philippine literature. These literary contributions played a crucial role in shaping the cultural landscape of the country and continue to be celebrated today. Some of the significant works from this period include:

- “Without Seeing the Dawn” by Stevan Javellana: This novel follows the story of a young Ilocano farm boy named Carding and his journey during the Japanese occupation in World War II. It explores themes of resilience, sacrifice, and the complexities of colonialism.

- “The Hand of the Enemy” by Kerima Polotan: This collection of short stories delves into the everyday lives of ordinary Filipinos as they navigate the challenges and realities of post-war society. It highlights the struggles faced by individuals in the aftermath of the war and offers profound insights into the human condition.

- “The Woman Who Had Two Navels” by Nick Joaquin: Regarded as a masterpiece of Philippine literature, this novel delves into themes of identity, history, and post-colonialism. It tells the story of a Filipino woman who believes she possesses two navels, symbolizing the dualities within Philippine society.

Notable writers during the post-war period included Francisco Sionil Jose, NVM Gonzales, and F. Hidalgo. These literary giants contributed immensely to the literary landscape, captivating readers with their profound insights, vivid storytelling, and poignant exploration of the Filipino experience.

Impact of Martial Law on Philippine Literature

The imposition of martial law in 1972 had a profound and lasting impact on Philippine literature. The government’s censorship and repression during this period severely curtailed the freedom of expression, suppressing critical voices and stifling artistic creativity. Writers and artists found themselves facing restrictions and threats, leading to a climate of fear and self-censorship.

However, the spirit of resistance prevailed, and Filipino writers persisted in their pursuit of creative expression. Many authors turned to underground publications to continue sharing their stories and perspectives, defying the authoritarian regime. These underground publications became a catalyst for dissent and served as a platform for voices that were silenced in mainstream media.

“During those dark years of martial law , we had to find ways to subvert the system and make our voices heard. Literature became a means of resistance, a tool for capturing the truth buried beneath the surface.” – NVM Gonzales, acclaimed Filipino writer

The works produced during this period were a reflection of the struggle and aspirations of the Filipino people for freedom and democracy. They portrayed the harsh realities of life under martial law , the human rights violations, and the call for justice. Through creative storytelling and powerful imagery, writers shed light on the suppressed truths and gave voice to the marginalized.

Notable Works During Martial Law

These works, despite the risks involved, became symbols of resistance and resilience against the oppressive regime. They not only captured the dark years of martial law but also inspired generations to fight for justice and uphold democratic values.

Although martial law brought immense challenges to Philippine literature, it also sparked a sense of unity among writers, artists, and activists. It fostered a collective spirit of defiance and a determination to preserve the power of storytelling. Despite the suppression , the written word continued to serve as a weapon against injustice and an instrument for social change.

The post-war era from 1946 to 1972 in the Philippines was a transformative period for Philippine literature and arts. It was a time of evolution, as new genres and styles emerged, and various themes were explored in literature. Despite challenges such as censorship and political repression, Filipino artists and writers persevered, expressing their creativity and engaging in societal discourse.

The impact of the post-war period on Philippine literature and arts cannot be overstated. It shaped the cultural landscape of the country, influencing the national identity and fostering a sense of artistic expression. The evolution of Philippine art forms during this time reflected the socio-cultural influences of the era.

Overall, the post-war era was a turning point for Philippine literature and arts. It showcased the resilience and creativity of Filipino artists and writers, leaving a lasting impact on the cultural heritage of the Philippines. The works produced during this period continue to be celebrated and studied, preserving the rich artistic legacy of the post-war era.