Search form

- Find Stories

- For Journalists

Emerging issues that could trouble teens

Stanford Medicine’s Vicki Harrison explains the forces impacting youth mental health today, and why it’s so important to involve teens in solutions.

Image credit: Getty Images

One of the most alarming developments across the United States in recent years has been the growing mental health crisis among children and adolescents.

The already dire situation is evolving 2024 already presenting a new set of challenges that Vicki Harrison, the program director at the Stanford Center for Youth Mental Health & Wellbeing , is closely monitoring and responding to.

Stanford Report sat down with Harrison to find out what concerns her the most about the upcoming year. Harrison also talked about some of the promising ways she and her colleagues are responding to the national crisis and the importance of bringing the youth perspective into that response.

Challenging current events

From the 2024 general election to evolving, international conflicts, today’s dialed-in youth have a lot to process. As teens turn to digital and social media sources to learn about current events and figure out where they stand on particular issues, the sheer volume of news online can feel overwhelming, stressful, and confusing.

One way Harrison is helping teens navigate the information they consume online is through Good for Media , a youth-led initiative that grew out of the Stanford Center for Youth Mental Health & Wellbeing to bring teens and young adults together to discuss using social media in a safe and healthy way. In addition to numerous youth-developed tools and videos, the team has a guide with tips to deal with the volume of news online and how to process the emotions that come with it.

Harrison points out that the tone of political discourse today – particularly discussions about reining in the rights a person has based on aspects of their identity, such as their religion, race, national origin, or gender – affects adolescents at a crucial time in their development, a period when they are exploring who they are and what they believe in.

“If their identity is being othered, criticized, or punished in some way, what messages is that sending to young people and how do they feel good about themselves?” Harrison said. “We can’t divorce these political and cultural debates from the mental health of young people.”

Harrison believes that any calls for solving the mental health crisis must acknowledge the critical importance of inclusion, dignity, and respect in supporting the mental health of young people.

Talking about mental health

Adolescence is a crucial time to develop coping skills to respond to stressful situations that arise – a skill not all teens and youth learn.

“It hasn’t always been normalized to talk about mental health and how to address feeling sad or worried about things,” Harrison said. “It’s not something that all of us have been taught to really understand and how to cope with. A lot of young people aren’t comfortable seeking professional services.”

The Stanford Center for Youth Mental Health & Wellbeing is helping young people get that extra bit of support to deal with problems before they get worse.

This year, they are rolling out stand-alone “one-stop-shop” health centers that offer youth 12-25 years old access to a range of clinical and counseling services with both trained professionals and peers. Called allcove , there are three locations open so far – Palo Alto, Redondo Beach, and San Mateo. More are set to open across the state in 2024.

“If we can normalize young people having an access point – and feeling comfortable accessing it – we can put them on a healthier track and get them any help they may need,” Harrison said.

Another emerging issue Harrison is monitoring is the growing role of social media influencers who talk openly about their struggles with mental health and well-being.

While this is helping bring awareness to mental health – which Harrison wants to see more of – she is also concerned about how it could lead some teens to mistake a normal, stressful life experience for a mental disorder and incorrectly self-diagnose themselves or to overgeneralize or misunderstand symptoms of mental health conditions. Says Harrison, “We want to see mental health destigmatized, but not oversimplified or minimized.”

“We can’t divorce these political and cultural debates from the mental health of young people.” —Vicki Harrison Program Director at the Stanford Center for Youth Mental Health & Wellbeing

Eyes on new technologies

Advances in technology – particularly generative AI – offer new approaches to improving teen well-being, such as therapeutic chatbots or detecting symptoms through keywords or patterns in speech.

“Digital solutions are a promising part of the continuum of care, but there’s the risk of rolling out things without the research backing them,” Harrison said.

Social media companies have come under scrutiny in recent years for inadequately safeguarding young adult mental health. Harrison hopes those mishaps serve as a cautionary tale for those applying AI tools more broadly.

There’s an opportunity, she says, to involve adolescents directly in making AI applications safe and effective. She and her team hope to engage young people with policy and industry and involve them in the design process, rather than as an afterthought.

“Can we listen to their ideas for how to make it better and how to make it work for them?” Harrison asks. “Giving them that agency is going to give us great ideas and make a better experience for them and for everyone using it.”

Harrison said she and her team are hoping to engage young people with policy and industry to elevate their ideas into the design process, rather than have it be an afterthought.

“There’s a lot of really motivated young people who see potential to do things differently and want to improve the world they inhabit,” Harrison said. “That’s why I always want to find opportunities to pass them the microphone and listen.”

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

The concerns and challenges of being a U.S. teen: What the data show

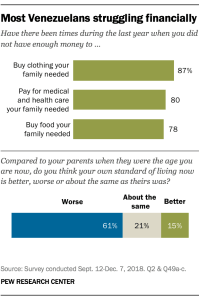

American teens have a lot on their minds. Substantial shares point to anxiety and depression, bullying, and drug and alcohol use (and abuse) as major problems among people their age, according to a new Pew Research Center survey of youth ages 13 to 17.

How common are these and other experiences among U.S. teens? We reviewed the most recent available data from government and academic researchers to find out:

Anxiety and depression

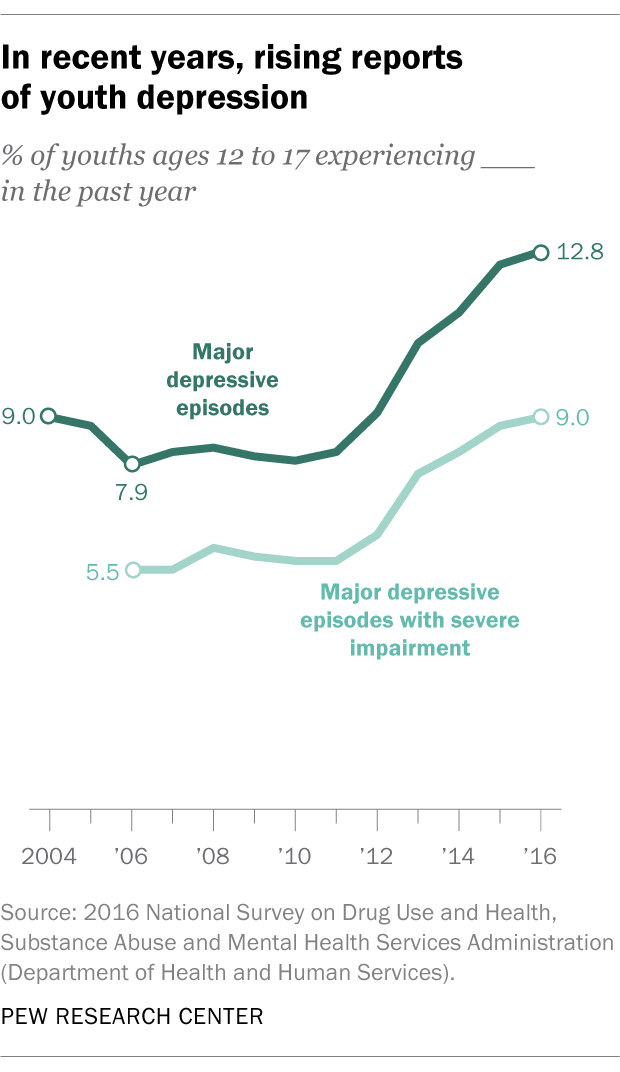

Serious mental stress is a fact of life for many American teens. In the new survey, seven-in-ten teens say anxiety and depression are major problems among their peers – a concern that’s shared by mental health researchers and clinicians .

Data on the prevalence of anxiety disorders is hard to come by among teens specifically. But 7% of youths ages 3 to 17 had such a condition in 2016-17, according to the National Survey of Children’s Health. Serious depression, meanwhile, has been on the rise among teens for the past several years, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health , an ongoing project of the federal Department of Health and Human Services. In 2016, 12.8% of youths ages 12 to 17 had experienced a major depressive episode in the past year, up from 8% as recently as 2010. For 9% of youths in 2016, their depression caused severe impairment. Fewer than half of youths with major depression said they’d been treated for it in the past year.

Alcohol and drugs

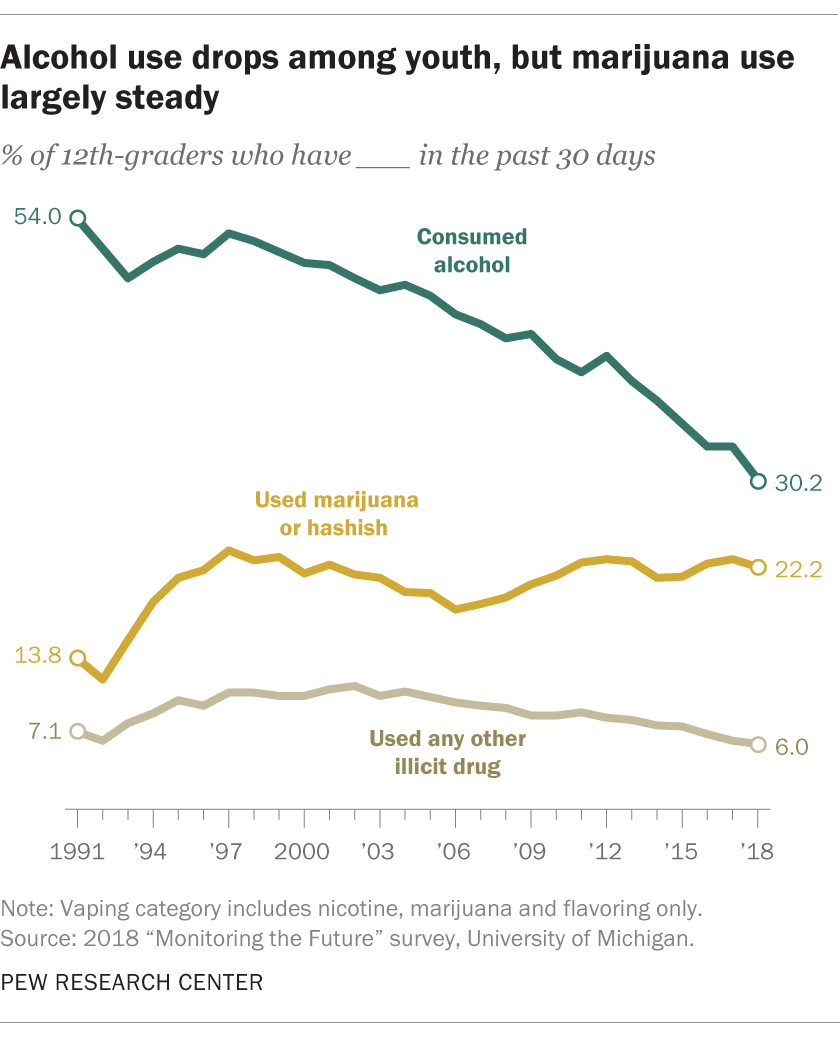

Anxiety and depression aren’t the only concerns for U.S. teens. Smaller though still substantial shares of teens in the Pew Research Center survey say drug addiction (51%) and alcohol consumption (45%) are major problems among their peers.

Fewer teens these days are drinking alcohol, according to the University of Michigan’s long-running Monitoring the Future survey, which tracks attitudes, values and behaviors of American youths, including their use of various legal and illicit substances. Last year, 30.2% of 12th-graders and 18.6% of 10th-graders had consumed alcohol in the past 30 days. Two decades earlier, those figures were 52% and 38.8%, respectively. (In the Center’s new survey, 16% of teens said they felt “a lot” or “some” pressure to drink alcohol.)

But the Michigan survey also found that, despite some ups and downs, use of marijuana (or its derivative, hashish) among 12th-graders is nearly as high as it was two decades ago. Last year, 22.2% reported using marijuana in the past 30 days, versus 22.8% in 1998. Past-month marijuana use among 10th-graders has declined a bit over that same period, from 18.7% to 16.7%, but is up from 14% in 2016.

Marijuana was by far the most commonly used drug among teens last year, as it has been for decades. While more than 10% of 12th-graders reported using some illicit drug other than marijuana in the late 1990s and early 2000s, that figure had fallen to 6% by last year.

The Michigan researchers noted that vaping, of both nicotine and marijuana, has jumped in popularity in the past few years. In 2018, 20.9% of 12th-graders and 16.1% of 10th-graders reported vaping nicotine in the past 30 days, about double the 2017 levels. By comparison, only 7.6% of 12th-graders and 4.2% of 10th-graders had smoked a cigarette in that time. And 7.5% of 12-graders and 7% of 10th-graders said they’d vaped marijuana within the past month, up from 4.9% and 4.3%, respectively, in 2017.

Bullying and cyberbullying

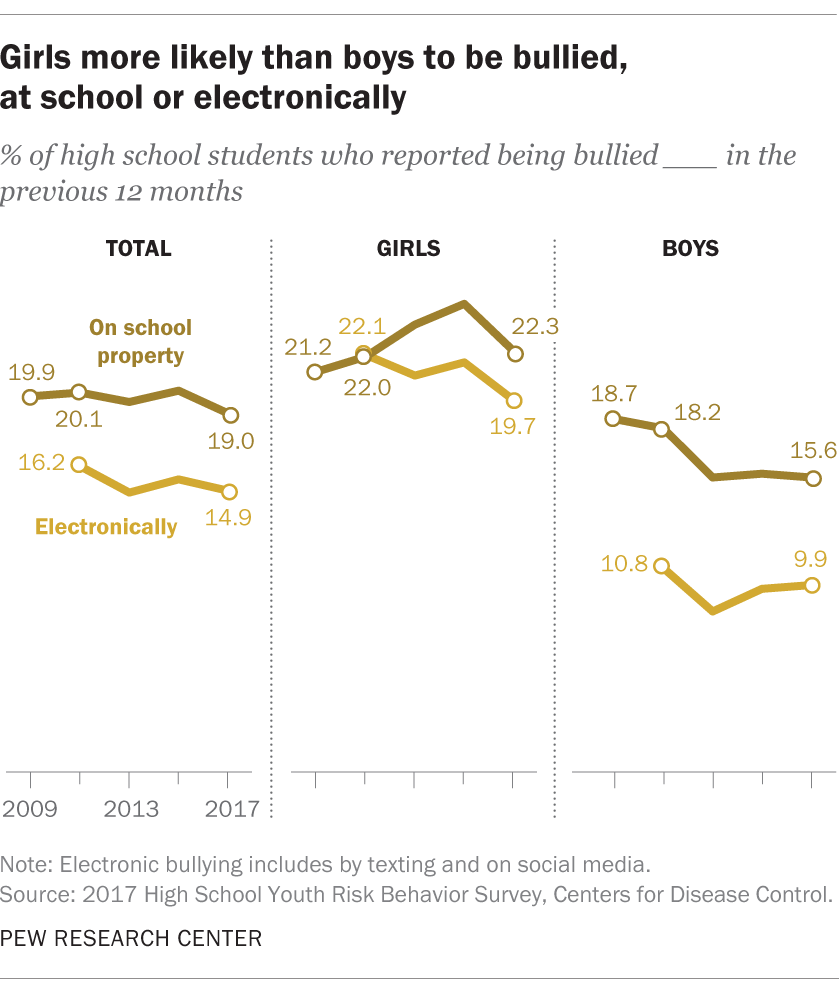

Issues of personal safety also are on U.S. teens’ minds. The Center’s survey found that 55% of teens said bullying was a major problem among their peers, while a third called gangs a major problem.

Bullying rates have held steady in recent years, according to a survey of youth risk behaviors by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About a fifth of high school students (19% in 2017) reported being bullied on school property in the past 12 months, and 14.9% said they’d experienced cyberbullying (via texts, social media or other digital means) in the previous year. In both cases, girls, younger students, and students who identified as gay, lesbian or bisexual were more likely to say they’d been bullied.

As for gangs, the share of students ages 12 to 18 who said gangs were present at their school fell from 20.1% in 2001 to 10.7% in 2015, according to a report on school safety from the federal departments of Education and Justice. Black and Hispanic students, as well as students in urban schools, were most likely to report the presence of gangs at school, but even for those groups the shares reporting this fell sharply between 2001 and 2015, the most recent year for which data are available.

Four-in-ten teens say poverty is a major problem among their peers, according to the Center’s new report. In 2017, about 2.2 million 15- to 17-year-olds (17.6%) were living in households with incomes below the poverty level – up from 16.3% in 2009, but down from 18.9% in 2014, based on our analysis of Census data. Black teens were more than twice as likely as white teens to live in households below the poverty level (30.4% versus 14%); however, the share of white teens in below-poverty-level households had risen from 2009 (when it was 12.1%), while the share of black teens in below-poverty-level households was almost unchanged.

Teen pregnancy

Far fewer U.S. teens are having to juggle adolescence and parenthood, as teen births continue their long-term decline . Among 15- to 19-year-olds, the overall birthrate has fallen by two-thirds since 1991 – from 61.8 live births per 1,000 women to 20.3 in 2016 , according to the CDC. All racial and ethnic groups have witnessed teen-birthrate declines of varying degrees: Among non-Hispanic blacks, for example, the rate fell from 118.2 live births per 1,000 in 1991 to 29.3 in 2016 .

- Age & Generations

- Drug Policy

- Health Policy

- Medicine & Health

- Teens & Youth

Drew DeSilver is a senior writer at Pew Research Center

How Teens and Parents Approach Screen Time

Who are you the art and science of measuring identity, u.s. centenarian population is projected to quadruple over the next 30 years, older workers are growing in number and earning higher wages, teens, social media and technology 2023, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

Subscribe or renew today

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

Social media harms teens’ mental health, mounting evidence shows. what now.

Understanding what is going on in teens’ minds is necessary for targeted policy suggestions

Most teens use social media, often for hours on end. Some social scientists are confident that such use is harming their mental health. Now they want to pinpoint what explains the link.

Carol Yepes/Getty Images

Share this:

By Sujata Gupta

February 20, 2024 at 7:30 am

In January, Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook’s parent company Meta, appeared at a congressional hearing to answer questions about how social media potentially harms children. Zuckerberg opened by saying: “The existing body of scientific work has not shown a causal link between using social media and young people having worse mental health.”

But many social scientists would disagree with that statement. In recent years, studies have started to show a causal link between teen social media use and reduced well-being or mood disorders, chiefly depression and anxiety.

Ironically, one of the most cited studies into this link focused on Facebook.

Researchers delved into whether the platform’s introduction across college campuses in the mid 2000s increased symptoms associated with depression and anxiety. The answer was a clear yes , says MIT economist Alexey Makarin, a coauthor of the study, which appeared in the November 2022 American Economic Review . “There is still a lot to be explored,” Makarin says, but “[to say] there is no causal evidence that social media causes mental health issues, to that I definitely object.”

The concern, and the studies, come from statistics showing that social media use in teens ages 13 to 17 is now almost ubiquitous. Two-thirds of teens report using TikTok, and some 60 percent of teens report using Instagram or Snapchat, a 2022 survey found. (Only 30 percent said they used Facebook.) Another survey showed that girls, on average, allot roughly 3.4 hours per day to TikTok, Instagram and Facebook, compared with roughly 2.1 hours among boys. At the same time, more teens are showing signs of depression than ever, especially girls ( SN: 6/30/23 ).

As more studies show a strong link between these phenomena, some researchers are starting to shift their attention to possible mechanisms. Why does social media use seem to trigger mental health problems? Why are those effects unevenly distributed among different groups, such as girls or young adults? And can the positives of social media be teased out from the negatives to provide more targeted guidance to teens, their caregivers and policymakers?

“You can’t design good public policy if you don’t know why things are happening,” says Scott Cunningham, an economist at Baylor University in Waco, Texas.

Increasing rigor

Concerns over the effects of social media use in children have been circulating for years, resulting in a massive body of scientific literature. But those mostly correlational studies could not show if teen social media use was harming mental health or if teens with mental health problems were using more social media.

Moreover, the findings from such studies were often inconclusive, or the effects on mental health so small as to be inconsequential. In one study that received considerable media attention, psychologists Amy Orben and Andrew Przybylski combined data from three surveys to see if they could find a link between technology use, including social media, and reduced well-being. The duo gauged the well-being of over 355,000 teenagers by focusing on questions around depression, suicidal thinking and self-esteem.

Digital technology use was associated with a slight decrease in adolescent well-being , Orben, now of the University of Cambridge, and Przybylski, of the University of Oxford, reported in 2019 in Nature Human Behaviour . But the duo downplayed that finding, noting that researchers have observed similar drops in adolescent well-being associated with drinking milk, going to the movies or eating potatoes.

Holes have begun to appear in that narrative thanks to newer, more rigorous studies.

In one longitudinal study, researchers — including Orben and Przybylski — used survey data on social media use and well-being from over 17,400 teens and young adults to look at how individuals’ responses to a question gauging life satisfaction changed between 2011 and 2018. And they dug into how the responses varied by gender, age and time spent on social media.

Social media use was associated with a drop in well-being among teens during certain developmental periods, chiefly puberty and young adulthood, the team reported in 2022 in Nature Communications . That translated to lower well-being scores around ages 11 to 13 for girls and ages 14 to 15 for boys. Both groups also reported a drop in well-being around age 19. Moreover, among the older teens, the team found evidence for the Goldilocks Hypothesis: the idea that both too much and too little time spent on social media can harm mental health.

“There’s hardly any effect if you look over everybody. But if you look at specific age groups, at particularly what [Orben] calls ‘windows of sensitivity’ … you see these clear effects,” says L.J. Shrum, a consumer psychologist at HEC Paris who was not involved with this research. His review of studies related to teen social media use and mental health is forthcoming in the Journal of the Association for Consumer Research.

Cause and effect

That longitudinal study hints at causation, researchers say. But one of the clearest ways to pin down cause and effect is through natural or quasi-experiments. For these in-the-wild experiments, researchers must identify situations where the rollout of a societal “treatment” is staggered across space and time. They can then compare outcomes among members of the group who received the treatment to those still in the queue — the control group.

That was the approach Makarin and his team used in their study of Facebook. The researchers homed in on the staggered rollout of Facebook across 775 college campuses from 2004 to 2006. They combined that rollout data with student responses to the National College Health Assessment, a widely used survey of college students’ mental and physical health.

The team then sought to understand if those survey questions captured diagnosable mental health problems. Specifically, they had roughly 500 undergraduate students respond to questions both in the National College Health Assessment and in validated screening tools for depression and anxiety. They found that mental health scores on the assessment predicted scores on the screenings. That suggested that a drop in well-being on the college survey was a good proxy for a corresponding increase in diagnosable mental health disorders.

Compared with campuses that had not yet gained access to Facebook, college campuses with Facebook experienced a 2 percentage point increase in the number of students who met the diagnostic criteria for anxiety or depression, the team found.

When it comes to showing a causal link between social media use in teens and worse mental health, “that study really is the crown jewel right now,” says Cunningham, who was not involved in that research.

A need for nuance

The social media landscape today is vastly different than the landscape of 20 years ago. Facebook is now optimized for maximum addiction, Shrum says, and other newer platforms, such as Snapchat, Instagram and TikTok, have since copied and built on those features. Paired with the ubiquity of social media in general, the negative effects on mental health may well be larger now.

Moreover, social media research tends to focus on young adults — an easier cohort to study than minors. That needs to change, Cunningham says. “Most of us are worried about our high school kids and younger.”

And so, researchers must pivot accordingly. Crucially, simple comparisons of social media users and nonusers no longer make sense. As Orben and Przybylski’s 2022 work suggested, a teen not on social media might well feel worse than one who briefly logs on.

Researchers must also dig into why, and under what circumstances, social media use can harm mental health, Cunningham says. Explanations for this link abound. For instance, social media is thought to crowd out other activities or increase people’s likelihood of comparing themselves unfavorably with others. But big data studies, with their reliance on existing surveys and statistical analyses, cannot address those deeper questions. “These kinds of papers, there’s nothing you can really ask … to find these plausible mechanisms,” Cunningham says.

One ongoing effort to understand social media use from this more nuanced vantage point is the SMART Schools project out of the University of Birmingham in England. Pedagogical expert Victoria Goodyear and her team are comparing mental and physical health outcomes among children who attend schools that have restricted cell phone use to those attending schools without such a policy. The researchers described the protocol of that study of 30 schools and over 1,000 students in the July BMJ Open.

Goodyear and colleagues are also combining that natural experiment with qualitative research. They met with 36 five-person focus groups each consisting of all students, all parents or all educators at six of those schools. The team hopes to learn how students use their phones during the day, how usage practices make students feel, and what the various parties think of restrictions on cell phone use during the school day.

Talking to teens and those in their orbit is the best way to get at the mechanisms by which social media influences well-being — for better or worse, Goodyear says. Moving beyond big data to this more personal approach, however, takes considerable time and effort. “Social media has increased in pace and momentum very, very quickly,” she says. “And research takes a long time to catch up with that process.”

Until that catch-up occurs, though, researchers cannot dole out much advice. “What guidance could we provide to young people, parents and schools to help maintain the positives of social media use?” Goodyear asks. “There’s not concrete evidence yet.”

More Stories from Science News on Science & Society

Separating science fact from fiction in Netflix’s ‘3 Body Problem’

Language models may miss signs of depression in Black people’s Facebook posts

Aimee Grant investigates the needs of autistic people

In ‘Get the Picture,’ science helps explore the meaning of art

What Science News saw during the solar eclipse

During the awe of totality, scientists studied our planet’s reactions

Your last-minute guide to the 2024 total solar eclipse

Protein whisperer Oluwatoyin Asojo fights neglected diseases

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 07 October 2021

Young people’s mental health is finally getting the attention it needs

You have full access to this article via your institution.

A kite-flying festival in a refugee camp near Syria’s border with Turkey. The event was organized in July 2020 to support the health and well-being of children fleeing violence in Syria. Credit: Muhammed Said/Anadolu Agency/Getty

Worldwide, at least 13% of people between the ages of 10 and 19 live with a diagnosed mental-health disorder, according to the latest State of the World’s Children report , published this week by the United Nations children’s charity UNICEF. It’s the first time in the organization’s history that this flagship report has tackled the challenges in and opportunities for preventing and treating mental-health problems among young people. It reveals that adolescent mental health is highly complex, understudied — and underfunded. These findings are echoed in a parallel collection of review articles published this week in a number of Springer Nature journals.

Anxiety and depression constitute more than 40% of mental-health disorders among young people (those aged 10–19). UNICEF also reports that, worldwide, suicide is the fourth most-common cause of death (after road injuries, tuberculosis and interpersonal violence) among adolescents (aged 15–19). In eastern Europe and central Asia, suicide is the leading cause of death for young people in that age group — and it’s the second-highest cause in western Europe and North America.

Collection: Promoting youth mental health

Sadly, psychological distress among young people seems to be rising. One study found that rates of depression among a nationally representative sample of US adolescents (aged 12 to 17) increased from 8.5% of young adults to 13.2% between 2005 and 2017 1 . There’s also initial evidence that the coronavirus pandemic is exacerbating this trend in some countries. For example, in a nationwide study 2 from Iceland, adolescents (aged 13–18) reported significantly more symptoms of mental ill health during the pandemic than did their peers before it. And girls were more likely to experience these symptoms than were boys.

Although most mental-health disorders arise during adolescence, UNICEF says that only one-third of investment in mental-health research is targeted towards young people. Moreover, the research itself suffers from fragmentation — scientists involved tend to work inside some key disciplines, such as psychiatry, paediatrics, psychology and epidemiology, and the links between research and health-care services are often poor. This means that effective forms of prevention and treatment are limited, and lack a solid understanding of what works, in which context and why.

This week’s collection of review articles dives deep into the state of knowledge of interventions — those that work and those that don’t — for preventing and treating anxiety and depression in young people aged 14–24. In some of the projects, young people with lived experience of anxiety and depression were co-investigators, involved in both the design and implementation of the reviews, as well as in interpretation of the findings.

Quest for new therapies

Worldwide, the most common treatment for anxiety and depression is a class of drug called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which increase serotonin levels in the brain and are intended to enhance emotion and mood. But their modest efficacy and substantial side effects 3 have spurred the study of alternative physiological mechanisms that could be involved in youth depression and anxiety, so that new therapeutics can be developed.

Mental health: build predictive models to steer policy

For example, researchers have been investigating potential links between depression and inflammatory disorders — such as asthma, cardiovascular disease and inflammatory bowel disease. This is because, in many cases, adults with depression also experience such disorders. Moreover, there’s evidence that, in mice, changes to the gut microbiota during development reduce behaviours similar to those linked to anxiety and depression in people 4 . That suggests that targeting the gut microbiome during adolescence could be a promising avenue for reducing anxiety in young people. Kathrin Cohen Kadosh at the University of Surrey in Guildford, UK, and colleagues reviewed existing reports of interventions in which diets were changed to target the gut microbiome. These were found to have had minimal effect on youth anxiety 5 . However, the authors urge caution before such a conclusion can be confirmed, citing methodological limitations (including small sample sizes) among the studies they reviewed. They say the next crop of studies will need to involve larger-scale clinical trials.

By contrast, researchers have found that improving young people’s cognitive and interpersonal skills can be more effective in preventing and treating anxiety and depression under certain circumstances — although the reason for this is not known. For instance, a concept known as ‘decentring’ or ‘psychological distancing’ (that is, encouraging a person to adopt an objective perspective on negative thoughts and feelings) can help both to prevent and to alleviate depression and anxiety, report Marc Bennett at the University of Cambridge, UK, and colleagues 6 , although the underlying neurobiological mechanisms are unclear.

In addition, Alexander Daros at the Campbell Family Mental Health Institute in Toronto, Canada, and colleagues report a meta-analysis of 90 randomized controlled trials. They found that helping young people to improve their emotion-regulation skills, which are needed to control emotional responses to difficult situations, enables them to cope better with anxiety and depression 7 . However, it is still unclear whether better regulation of emotions is the cause or the effect of these improvements.

Co-production is essential

It’s uncommon — but increasingly seen as essential — that researchers working on treatments and interventions are directly involving young people who’ve experienced mental ill health. These young people need to be involved in all aspects of the research process, from conceptualizing to and designing a study, to conducting it and interpreting the results. Such an approach will lead to more-useful science, and will lessen the risk of developing irrelevant or inappropriate interventions.

Science careers and mental health

Two such young people are co-authors in a review from Karolin Krause at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, Canada, and colleagues. The review explored whether training in problem solving helps to alleviate depressive symptoms 8 . The two youth partners, in turn, convened a panel of 12 other youth advisers, and together they provided input on shaping how the review of the evidence was carried out and on interpreting and contextualizing the findings. The study concluded that, although problem-solving training could help with personal challenges when combined with other treatments, it doesn’t on its own measurably reduce depressive symptoms.

The overarching message that emerges from these reviews is that there is no ‘silver bullet’ for preventing and treating anxiety and depression in young people — rather, prevention and treatment will need to rely on a combination of interventions that take into account individual needs and circumstances. Higher-quality evidence is also needed, such as large-scale trials using established protocols.

Along with the UNICEF report, the studies underscore the transformational part that funders must urgently play, and why researchers, clinicians and communities must work together on more studies that genuinely involve young people as co-investigators. Together, we can all do better to create a brighter, healthier future for a generation of young people facing more challenges than ever before.

Nature 598 , 235-236 (2021)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-02690-5

Twenge, J. M., Cooper, A. B., Joiner, T. E., Duffy, M. E. & Binau, S. G. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 128 , 185–199 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Thorisdottir, I. E. et al. Lancet Psychiatr. 8 , 663–672 (2021).

Article Google Scholar

Murphy, S. E. et al. Lancet Psychiatr. 8 , 824–835 (2021).

Murray, E. et al. Brain Behav. Immun. 81 , 198–212 (2019).

Cohen Kadosh, K. et al. Transl. Psychiatr. 11 , 352 (2021).

Bennett, M. P. et al. Transl Psychiatr. 11 , 288 (2021).

Daros, A. R. et al. Nature Hum. Behav . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01191-9 (2021).

Krause, K. R. et al. BMC Psychiatr. 21 , 397 (2021).

Download references

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

- Psychiatric disorders

- Public health

Targeting RNA opens therapeutic avenues for Timothy syndrome

News & Views 24 APR 24

The rise of eco-anxiety: scientists wake up to the mental-health toll of climate change

News Feature 10 APR 24

Use fines from EU social-media act to fund research on adolescent mental health

Correspondence 09 APR 24

WHO redefines airborne transmission: what does that mean for future pandemics?

News 24 APR 24

More work is needed to take on the rural wastewater challenge

Correspondence 23 APR 24

Monkeypox virus: dangerous strain gains ability to spread through sex, new data suggest

News 23 APR 24

NIH pay raise for postdocs and PhD students could have US ripple effect

News 25 APR 24

India’s 50-year-old Chipko movement is a model for environmental activism

The Middle East’s largest hypersaline lake risks turning into an environmental disaster zone

Postdoctoral Fellowships: Early Diagnosis and Precision Oncology of Gastrointestinal Cancers

We currently have multiple postdoctoral fellowship positions within the multidisciplinary research team headed by Dr. Ajay Goel, professor and foun...

Monrovia, California

Beckman Research Institute, City of Hope, Goel Lab

Postdoctoral Associate- Computational Spatial Biology

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Staff Scientist - Genetics and Genomics

Technician - senior technician in cell and molecular biology.

APPLICATION CLOSING DATE: 24.05.2024 Human Technopole (HT) is a distinguished life science research institute founded and supported by the Italian ...

Human Technopole

Postdoctoral Fellow

The Dubal Laboratory of Neuroscience and Aging at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) seeks postdoctoral fellows to investigate the ...

San Francisco, California

University of California, San Francsico

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

A Mental Health Crisis Among the Young

More from our inbox:, ‘i have an emergency alert for democrats’, ‘an endlessly increasing pentagon budget’, move away from coal.

To the Editor:

Re “ Alarm Sounded on Youth Mental Health ” (news article, Dec. 8):

There is a serious mental health crisis for the youth of America, according to Dr. Vivek Murthy, surgeon general of the United States. There is a mountain of evidence supporting this.

Pediatric hospitals are overrun with mental health cases. There is a lot of hand-wringing but little more. A thorough analysis of our cultural flaws is seriously lacking.

These children and adolescents are bombarded with a toxic mix of vicious social media and harmful violent video games, television shows and films. In addition, this is the only advanced nation in the world where going to school has turned into a form of Russian roulette.

The discordant state of politics guarantees that nothing will change for these unfortunate youth. Our culture, which emphasizes winning at sports, egotism and accumulation of wealth, creates a weakened society unable to comprehend and deal with its most serious problems. The Covid pandemic is exhibit A.

The mental health crisis of American youth is a function of a culture that promotes ignorance, self-indulgence and self-aggrandizement with little sense of decency, mutual respect or self-reflection. How do you repair a defective culture? I am not sure, but it needs to start with a serious examination of its substantial flaws.

Arnold R. Eiser Philadelphia The writer, a doctor, is a senior adjunct fellow at the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics and an adjunct fellow at the Center for Public Health Initiatives at the University of Pennsylvania.

Re “ Schools in Bind as Bitter Feuds Cripple Board ” (front page, Dec. 2):

As schools across the country confront “an array of urgent challenges,” we’re failing to address the most systemic, the most alarming and the most dangerous crisis of all: a youth mental health emergency. The lack of a significant national response is stunning.

Not only do we need to shift our collective focus, but we also need to shift the culture of our schools if we are to meaningfully address this mental health crisis that is exhausting and overstretching entire school communities.

That means putting an end to toxic school stressors that have long caused anxiety and depression in young people, and starting to create environments that are humane for students, teachers and families. Instead of being driven by a narrow vision of achievement and success, our schools must prioritize the experiences that support health — like connection, agency and meaningful learning.

If we finally bring humanity to our schools, maybe then not only will our kids be healthier, but also we as a society can start to heal together.

Vicki Abeles Lafayette, Calif. The writer is the author of “Beyond Measure: Rescuing an Overscheduled, Overtested, Underestimated Generation,” and director of the documentaries “Race to Nowhere” and “Beyond Measure.”

Re “ Democrats’ Dangerous Appetite for Eating Their Own ,” by Frank Bruni (newsletter, nytimes.com, Dec. 9):

I have an Emergency Alert for Democrats. Our nation’s democratic form of government is in the cross hairs. The political moment is grave. It is not clear if our remarkable democracy will survive the vicious and organized assault from the right, nor is it clear if the Dems have the clarity and stamina to save it.

Remember that you are politicians, elected to meet the political moment, equipped and focused on what is now the greatest threat to our country since the Civil War. Critical issues of climate change, equality and health care must be addressed.

But if we lose the country as we have known it, how will it be possible to fight for those things? It is a terrifying prospect.

Susan Teicher Urbana, Ill.

“ Houses Passes Defense Bill in Rare Display of Unity to Salvage Shared Priority ” (news article, Dec. 8) didn’t do justice to the sheer size of the Pentagon budget. After months of intense debate over the president’s Build Back Better, at $1.8 trillion over 10 years, a Pentagon budget with annual spending ($768 billion) four times as much as those domestic investments is astounding.

The U.S. military budget is larger than that of the next 11 countries combined, and more than twice that of China, a constantly cited justification for more spending. After 20 years, the end of the war in Afghanistan resulted not in a budget decrease, but more increases. And Congress cut Build Back Better in half, but added to the president’s defense budget request.

The majority of Americans don’t support an endlessly increasing Pentagon budget. But double standards in Congress combined with low media coverage tip the scales toward that outcome, time and again.

Lindsay Koshgarian Northampton, Mass. The writer is program director for the National Priorities Project at the Institute for Policy Studies.

Re “ A Sticking Point in Climate Plan ” (Business, Dec. 13):

The proper function of Republicans (and of Senator Joe Manchin, a Democrat) is to jump right in on clean energy plans from the get-go, ensuring not just benefits and transition pay, but also a robust retraining program for displaced workers — a program conceived and monitored in cooperation with those workers and their advocates.

In the current polarized era of dysfunction, coal miners’ political advocates have abdicated this vital responsibility. By denying, obfuscating, obstructing and slow-walking the necessary decarbonization of the economy, they have fostered a double disaster.

Coal miners will be shortchanged by poorly thought out Democratic policies, while climate catastrophe will proceed apace.

Jeff Freeman Rahway, N.J.

Being a teen comes with exciting milestones that double as challenges – like becoming independent, navigating high school and forming new relationships. For all the highs that come with getting a driver’s license or acing that difficult test, there are lows that come with growing up in a rapidly changing world being shaped by the COVID-19 pandemic, social media and distance learning.

Teens’ brains are growing and developing, and the ways they process their experiences and spend their time are crucial to their development. Each great experience and every embarrassing moment can impact their mental health.

Sometimes a mood is about more than just being lonely or angry or frustrated.

Mental health challenges are different than situational sadness or fatigue. They’re more severe and longer-lasting, and they can have a large impact on daily life. Some common mental health challenges are anxiety, depression, eating disorders, substance use, and experiencing trauma. They can affect a teen’s usual way of thinking, feeling or acting, and interfere with daily life.

Adding to the urgency: Mental health challenges among teens are not uncommon. Up to 75% of mental health challenges emerge during adolescence, and according to the Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) curriculum, one in five teens has had a serious mental health disorder at some point in their life.

Not every mental health challenge will be diagnosed as a mental disorder, but every challenge should be taken seriously.

A mental health challenge left unchecked can become a more serious problem that also impacts physical health — think of how substance use, and changes in sleep patterns and eating habits affect the body as well as the mind. Signs of fatigue, withdrawing socially or changes in mood may point to an emerging mental health challenge like a depressive or substance use disorder.

As teens mature, they begin spending more time with their friends, gain a sense of identity and purpose, and become more independent. All of these experiences are crucial for their development, and a mental health challenge can disrupt or complicate that development. Depending on the severity of the mental health challenge, the effects can last long into adulthood if left unaddressed.

How do we address teens’ mental health?

Teens need tools to talk about what’s going on with them, and they need tools for when their friends reach out to them. Research shows that teens are more likely to talk to their friends than an adult about troubles they’re facing.

That’s why it’s important to talk to teens about the challenges they may deal with as they grow up and navigate young adulthood. They need to know it’s OK to sometimes feel sad, angry, alone, and frustrated. But persistent problems may be pointing to something else, and it is crucial to be able to recognize early warning signs so teens can get appropriate help in a timely manner. teen Mental Health First Aid teaches high school students in grades 10-12 how to identify, understand and respond to signs of a mental health problem or crisis among their friends — and how to bring in a trusted adult when it’s appropriate and necessary. With proper care and treatment, many teens with mental health or substance use challenges can recover. The first step is getting help.

Learn more about teen Mental Health First Aid by watching this video and checking out our blog . Your school or youth-serving organization can also apply to bring this training to your community.

teen Mental Health First Aid is run by the National Council for Mental Wellbeing and supported by Lady Gaga’s Born This Way Foundation.

Resource Guide:

- Mental Health First Aid USA. (2020). teen Mental Health First Aid USA: A manual for young people in 10 th -12 th grade helping their friends. Washington, DC: National Council for Mental Wellbeing.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2020). The Teen Brain: 7 Things to Know. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/the-teen-brain-7-things-to-know/index.shtml.

Get the latest MHFA blogs, news and updates delivered directly to your inbox so you never miss a post.

Share and help spread the word.

Related stories.

No related posts.

Adolescent Health and Well-Being: Issues, Challenges, and Current Status in India

- First Online: 08 March 2022

Cite this chapter

- Nandita Babu 3 &

- Mehreen Fatima 3

1324 Accesses

Adolescence is the developmental stage between childhood and adulthood marked by considerable growth in physical, cognitive, and socio-emotional domains. It is considered as a preparatory phase for adulthood, and therefore, well-being during adolescence would predict well-being during adulthood and age ahead. During this stage of life, children have specific needs that vary based upon gender, socio-economic status, and overall cultural belief system of the community. In order to understand the process of development during adolescence, it is extremely important to study the systems like family, school neighborhood, and community in which the adolescents live. Few researches in India have studied these processes to understand the adolescent’s need at large. With about 373 million persons between the ages of 10 and 24 years, India has the largest number of young people of any country in the world and that makes it a more viable area for research, intervention, and policy implementation. To meet the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s, and Adolescents’ health, the Government of India have prioritized adolescent health in various programs and policies. However, in spite of all the attempts by researchers, practitioners, and policymakers, there is still a major gap which needs to be filled up to reach the 2030 SDG goals. Therefore, the need of the hour is to follow a multidisciplinary approach toward research, policy formulation, and intervention for psychosocial and physical health of adolescents. This chapter is an attempt to discuss the major issues of adolescent development in the socio-cultural context of India, identify the research gaps, and analyze the policies and programs for positive developmental outcomes for the young people in India.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Adolescence Education Programme. Ministry of Human Resource Development. Available from: https://www.india.gov.in/adolescence-education-programme . Adolescence Education Programme | National Portal of India

Agarwal, V., & Dhanasekaran, S. (2012). Harmful effects of media on children and adolescents. Journal of Indian Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 8 (2), 38–45.

Article Google Scholar

Ahmad, A., Khalique, N., Khan, Z., & Amir, A. (2020). Prevalence of psychosocial problems among school going male adolescents. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 32 (3), 219–221.

Balika Samriddhi Yojana. Ministry of women and child development, Government of India . Available from: https://www.india.gov.in/balika-samriddhi-yojana-ministry-women-and-child-development

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design . Harvard University Press.

Google Scholar

Chandrasekaran, V., Kamath, V. G., Ashok, L., Kamath, A., Hegde, A. P., & Devaramane, V. (2017). Role of micro- and mesosystems in shaping an adolescent. Journal of Nepal Paediatric Society, 37 (2), 178–183.

Chaurasia, K., & Ali, M. I. (2019). A comparative study of mental health of juvenile delinquent and normal adolescents. The International Journal of Indian Psychology, 7 (4), 829–834.

Dhawan, A., Pattanayak, R. D., Chopra, A., Tikoo, V. K., & Kumar, R. (2017). Pattern and profile of children using substances in India: Insights and recommendations. The National Medical Journal of India, 30 (4), 224–229.

Duncan, P. (2009, November 1). Use a strengths-based approach to adolescent preventive care. AAP News, 30 (11). Retrieved from: https://www.aappublications.org/content/30/11/13

Gaiha, S. M., Taylor Salisbury, T., Koschorke, M., Raman, U., & Petticrew, M. (2020). Stigma associated with mental health problems among young people in India: A systematic review of magnitude, manifestations and recommendations. BMC Psychiatry, 20 , 538.

Goel, R., & Malik, A. (2017). Risk taking and peer pressure in adolescents: A correlational study. Indian Journal of Health and Well-Being, 8 (12), 1528–1532.

Hameed & Mehrotra. (2017). Positive youth development programs for mental health promotion in Indian youth: An underutilized pathway. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health, 4 (10), 3488–3495.

Havighurst, R. J. (1952). Developmental tasks and education . David McKay.

Hossain, M. M., & Purohit, N. (2019). Improving child and adolescent mental health in India: Status, services, policies, and way forward. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 61 (4), 415–419.

Implementation guide on RCH II: Adolescent reproductive and sexual health strategy.

Integrated Child Protection Scheme. Ministry of Women and Child Development. Available from: https://wcd.nic.in/integrated-child-protection-scheme-ICPS

Kamaraj, D., Sivaprakasam, E., Ravichandran, L., & Pasupathy, U. (2016). Perception of health related quality of life in healthy Indian adolescents. International Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics, 3 (3), 692–699.

Kanwar, P. (2020). Pubertal development and problem behaviours in Indian adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25 (1), 753–764. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2020.1739089

Keyho, K., Gujar, N. M., & Ali, A. (2019). Prevalence of mental health status in adolescent school children of Kohima District, Nagaland. Annals of Indian Psychiatry, 3 ( 1 ), 39–42.

Kharod, N., & Kumar, D. (2015). Mental health status of school going adolescents in rural areas of Gujarat. Indian Journal of Youth and Adolescent Health, 2 (3), 17–21.

Khubchandani, J., Clark, J., & Kumar, R. (2014). Beyond controversies: Sexuality education for adolescents in India. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 3 (3), 175–179.

Kishori Shakti Yojana. Ministry of women and child development, Government of India . Available from: https://wcd.nic.in/kishori-shakti-yojana

Kumar, B. P., Eregowda, A.,Giliyaru, S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on the mental health of adolescents in India and their perceived causes of stress and anxiety. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health, 7 (12), 5048–5053.

Kumar, M. M., Priya, P. K.,Panigrahi, S. K., Raj, U., Pathak, V. K. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on adolescent health in India. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 9(11), 5484–5489.

Lavanya, T. P., & Manjula, M. (2017). Emotion Regulation and psychological problems among Indian college youth. Indian Journal of Social Psychiatry, 33 (4), 312–318.

Manning, M. L. (2002). Havighurst’s developmental tasks, young adolescents, and diversity. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 76 (2), 75–78.

Mehrotra, S. (2013). Feeling good and doing well? Testing efficacy of a mental health promotive intervention program for Indian Youth. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 5 (3), 28–42.

Minhas, S., Kunwar, R., & Sekhon, H. (2019). A review of adolescent reproductive and sexual health programs implemented in Sonitpur District, Assam. Medical Journal of Dr. D. Y. Patil Vidyapeeth, 12(5), 408–414.

National Rural Health Mission. Available from: http://origin.searo.who.int/entity/child_adolescent/topics/adolescent_health/rch_asrh_india.pdf .

National AIDS Prevention and Control Policy. National Health Portal of India. Available from: https://www.nhp.gov.in/national-aids-prevention-and-control-policy_pg . National AIDS Prevention and Control Policy | National Health Portal Of India (nhp.gov.in).

Nair, S., Ganjiwale, J., Kharod, N., Varma, J., & Nimbalkar, S. M. (2017). Epidemiological survey of mental health in adolescent school children of Gujarat, India. BMJ Paediatrics Open; 1:e000139. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2017-000139 .

National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005–06: India: Volume I. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International. Mumbai: IIPS. September 2007. Available from: http://www.rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-3%20Data/VOL-1/India_volume_I_corrected_17oct08.pdf .

National Mental Health Policy of India. Ministry of health and family welfare, Government of India . Available from: https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/National_Health_Mental_Policy.pdf .

National Plan of Action for Children. Ministry of Women and Child Development. Available from: https://wcd.nic.in/sites/default/files/National%20Plan%20of%20Action%202016.pdf . National Plan of Action 2016_cover (wcd.nic.in).

National Population Policy. Ministry of health and family welfare . Available from: https://www.nhp.gov.in/national-population-policy-2000_pg

National Youth Policy. Ministry of youth affairs and sports, Government of India . Available from: https://yas.nic.in/sites/default/files/National-Youth-Policy-Document.pdf

Nebhinani, N., & Jain, S. (2019). Adolescent mental health: Issues, challenges, and solutions. Annals of Indian Psychiatry, 3 (1), 4–7. Gale OneFile: Health and Medicine.

Palaniswamy, U., & Ponnuswami, I. (2013). Social changes and peer group influence among the adolescents pursuing under graduation. International Research Journal of Social Sciences, 2 (1), 1–5.

Patra, S., Patro, B. K. (2020). COVID-19 and adolescent mental health in India. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7 (12), 1015.

Positive Youth Development. Youth.gov. Retrieved from: https://youth.gov/youth-topics/positive-youth-development

Priyadarshini, R., Jasmine, S., Valarmathi, S., Kalpana, S., & Parameswari, S. (2013). Impact of media on the physical health of urban school children of age group 11–17 years in Chennai—A cross sectional study. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 9 (5), 30–35.

Rajiv Gandhi Scheme for Empowerment of Adolescent Girls: Sabla. Ministry of women and child development, Government of India . Available from: https://www.india.gov.in/rajiv-gandhi-scheme-empowerment-adolescent-girls-sabla

Rashtriya Kishor SwasthyaKaryakram. Ministry of health and family welfare . Available from: https://www.nhp.gov.in/rashtriya-kishor-swasthya-karyakram-rksk_pg

Roy, K., Shinde, S., Sarkar, B. K., Malik, K., Parikh, R., & Patel, V. (2019). India’s response to adolescent mental health: A policy review and stakeholder analysis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 54 , 405–414.

Sagar, R., Dandona, R., Gururaj, G., et al. (2020). The burden of mental disorders across the states of India: The Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2017. Lancet Psychiatry, 7 , 148–161.

Santhya, K. G., & Jejeebhoy, S. J. (2012). The sexual and reproductive health and rights of young people in India: A review of the situation. New Delhi: Population Council.

Saraswathi, T. S., & Oke, M. (2013). Ecology of adolescence in India. Psychological Studies, 58 , 353–364.

School Health Programme (SHP). Ministry of health and family welfare . Available from: https://nhm.gov.in/New_Updates_2018/NHM_Components/RMNCHA/AH/guidelines/Operational_guidelines_on_School_Health_Programme_under_Ayushman_Bharat.pdf

Seenivasan, P., & Kumar, C. P. (2014). A comparison of mental health of urban Indian adolescents among working and non-working mothers. Annals of Community Health, 2 (2), 39–43.

Sehgal, S. (2017). Identity development and familial relations: Particularly with respect to adolescence in India. The Delhi University Journal of the Humanities and the Social Sciences, 4 , 145–154.

Sinha Roy, A. K., Sau, M., Madhwani, K. P., Das, P., & Singh, J. K. (2018). A study on psychosocial problems among adolescents in urban slums in Kolkata, West Bengal. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health, 5 (11), 4932–4936.

Sitholey, P., Agarwal, V., & Vrat, S. (2013). Indian mental concepts on children and adolescents. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 55 (2), 277–282.

Sondhi, R. (2017). Parenting adolescents in India: A cultural perspective, child and adolescent mental health, Martin H. Maurer, IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/66451 . Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/books/child-and-adolescent-mental-health/parenting-adolescents-in-india-a-cultural-perspective

Steinberg, L. (2008). A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk taking. Developmental Review, 28 (1), 78–106.

Tanwar, K. C., & Priyanka. (2016). Impact of media violence on children’s aggressive behaviour . Indian Journal of Research, 5(6) , 241–245.

The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act (2015). Ministry of law and justice, Government of India . Available from: http://cara.nic.in/PDF/JJ%20act%202015.pdf

Underwood, L. A., & Washington, A. (2016). Mental illness and juvenile offenders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13 (2), 228.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). (2011). The state of the world’s children: Adolescence an age of opportunity. UNICEF.

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). (2013). UNFPA strategy on adolescents and youth . UNFPA.

Wasil, A. R., Park, S. J., Gillespie, S., Shingleton, R., Shinde, S., Natu, S., Weisz, J. R., Hollon, S. D., & DeRubeis, R. J. (2020). Harnessing single-session interventions to improve adolescent mental health and well-being in India: Development, adaptation, and pilot testing of online single-session interventions in Indian secondary schools. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 50 :101980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101980 .

WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP). World Health Organization (2008). Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/mhgap/en/

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Delhi University, New Delhi, India

Nandita Babu & Mehreen Fatima

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Sriperumbudur, Tamil Nadu, India

Sibnath Deb

Florida, FL, USA

Brian A. Gerrard

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Babu, N., Fatima, M. (2022). Adolescent Health and Well-Being: Issues, Challenges, and Current Status in India. In: Deb, S., Gerrard, B.A. (eds) Handbook of Health and Well-Being. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-8263-6_7

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-8263-6_7

Published : 08 March 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-16-8262-9

Online ISBN : 978-981-16-8263-6

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

- Currently reading: What problems are young people facing? We asked, you answered

- A new deal for the young: saving the environment

- A new deal for the young: funding higher education fairly

- A new deal for the young: building better jobs

- A new deal for the young: ensuring fair pensions

- A new deal for the young: how to fix the housing crisis

- ‘We are drowning in insecurity’: young people and life after the pandemic

What problems are young people facing? We asked, you answered

- What problems are young people facing? We asked, you answered on x (opens in a new window)

- What problems are young people facing? We asked, you answered on facebook (opens in a new window)

- What problems are young people facing? We asked, you answered on linkedin (opens in a new window)

- What problems are young people facing? We asked, you answered on whatsapp (opens in a new window)

Lucy Warwick-Ching

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A series of FT View editorials and daily online debates will make the case for a new deal for the young. Beginning on Monday 26 April, they will address housing, pensions, jobs, education, the climate and tax over the course of the week. Click to register for the events and see all the other articles

Growing inequality between generations has been exacerbated by the pandemic and has left many people in their teens, twenties and thirties feeling like they have got a raw deal.

The Financial Times wanted to bring those young people into a discussion about shifts in asset prices, pensions, education and the world of work so we launched a global survey. We asked people aged between 16 and 35 to tell us what life has been like for them in the pandemic, and which problems need fixing most urgently.

The survey was only open for one week but we had a record number of responses, with 1,700 people replying to the callout and spending an average of 30 minutes each on their responses.

While the majority of respondents were from the UK and US, others who shared their views were from Europe, Brazil, Egypt, and Asia-Pacific. Many of the respondents, though not all, were graduates who worked in sectors such as law, banking, media, education, science and technology. Many did not want to share their full names or personal details for fear of professional and personal repercussions.

People spoke of the difficulties — and benefits — of being young in today’s difficult economic times compared with their parents’ generation, and about issues relating to housing, education, jobs, pensions and the environment.

The responses formed the starting point for an in-depth analysis of the problems faced by young people today by Sarah O’Connor, our employment columnist. It is the first article in an FT series on what policies would make the economy work better for today’s youth.

Here we highlight some of the many hundreds of comments we received from readers:

Cramped housing

I absolutely cannot relate to mid career professionals being glad to be at home in their leafy three bedroom houses with gardens, when I have to have mid afternoon calls with the sound of my flatmates frying fish for lunch in the background. — A 20-year-old female reader living in London

The burden of student loans

Student loans feel like a unique problem for our generation. I can’t think of a similarity in the past when youth had such large financial burdens that can’t be discharged in most cases. Not that cancellation is necessarily the right choice. I knew what I signed up for, but what was the alternative, work in a coffee shop while the rest of my generation bettered themselves?

Mortgages and car payments just aren’t comparable to the $100k in loans I’ve been forced to deal with since I was 22. The rest seems similar. We have climate change and equality, my parents generations had communist totalitarian governments, nuclear war and . . . equality. — Matt, who works in Chicago, US

Mismatched ideas

The older generation has never understood that while our pay has increased it has been wiped out by extortionate rise in property prices. The older generation also thinks young people only enjoy spending money on experiences rather than saving money, which is not true. — A 30-year-old engineer living in the UK

Living with uncertainty

Older generations don’t feel the uncertainty we younger generation live with. Now it is more common for us to have more temporary jobs, for example, the gig economy. This uncertainty makes planning for future harder and makes taking risks impossible. — Ahmed, a lecturer living in Egypt

Scrap stamp duty on housing

The government needs to sort out house prices and stop inflating them. It should also scrap stamp duty and introduce annual property taxes instead. — A 25-year-old investment banker living in London

Emotionally better off than my parents

I know I’ll be better off than my parents. My mom came from an Italian immigrant family with seven siblings. I’m one of the first people to graduate from college with a four-year degree and one of the only people employed. Neither of my parents really ‘did’ therapy through their adult lives despite needing it, whereas I’ve had a therapist since my second year in college.

I think a common misperception about being better off is the focus on wealth — being better off also means being more emotionally and mentally healthy, which I know I am already better off than many of my family members. — Alicia, a financial analyst living in America

London feels increasingly full of anxious, burnt out 20- and 30-something-year-olds who spend half their income on a cramped flat with a damp problem and spend their weekends in the foetal position on their landlord’s Ikea sofa, endlessly scrolling through the latest app.

We have so much more than our parents did at our age, but also so much less. — A 25-year-old woman from the UK

Artificially high property prices

Current policies like Help to Buy are making things worse for young people in Britain. The prices of new builds are artificially inflated as builders know HTB can only be used on new builds! £450,000 for a one bed flat in London? Jog on. It’s insane. — Chris, in his late twenties living in London

Gen X doesn’t understand Gen Y

Generation X, doesn’t understand Generation Y, who doesn’t understand Generation Z — Andreas, a young doctor from Bulgaria

Regulate financial markets

I also have a feeling that regulating the financial markets would create more stability which would reduce the constant fear of a market meltdown — Kasper from Finland

Who is accountable?

Sustainability (renewable energy, mindful meat consumption, plastic usage awareness, social responsibility, ESG) are utmost key, and older generations seem to miss this. It feels they have put us in a stage where there is no going back, and there is no accountability whatsoever. — Renato, a risk manager from Brazil

Soaring rents

Many items that are considered a luxury to older generations, holidays, clothes, going out to eat, for example, are cheaper these days, but buying a house or renting is so much more expensive compared to when my parents were young. A lot of young people can afford the former not the latter, but for many older generations it seems the opposite was true, which creates contrasting views from each side about who has it worse. — Sophie, in her mid-twenties, from London

Young vs old

A number of older people I know are relatively sympathetic to a lot of the issues we face. There is a young versus old narrative pushed by certain sections of the media which, at least for many older people with families, has rung hollow with me. Generally they do recognise that we live in a more competitive world than they grew up in, for university places, jobs, housing etc. If anything I feel older generations probably understand younger people better than we understand them — Alex, a student solicitor in London

Cannot afford to buy a house

There is no acceptance that working from home is not feasible for younger people where you’re in significantly smaller accommodation. My company released an internal communication informing us how to be more efficient working in shared accommodation or working from your bedroom at the same time as starting consultation on closing all offices and homeworking permanently. — Lewis, who is working and studying in Bristol, UK

I have a mildly dystopian view

I feel older generations don’t understand the value of money, and it feels strange because my parents have lived a frugal life and I am doing well enough for myself, yet, given the economy, I feel compelled to save, while they don’t understand why I think thrice before every purchase.

On the issue of non-renewable resources, I feel that my parents have a particularly different mindset compared to mine; I have a mild compulsion to turn off any running tap or switch if it’s not being used. They have this comfort and faith that there will be enough for the coming generations, while I have a mildly dystopian view of the future Water/Resource Wars — Pia, a woman in her twenties in India

Steep housing costs

At my age on an apprentice’s salary my dad owned his own house and was buying and flipping more houses. I’ve got a masters degree, earning about 40 per cent more than the national average and I’m still struggling to find anywhere. They just don’t seem to understand, my dad refused to believe me until I showed him the tiny studio flats selling in my area for almost £300k — A data scientist in his late twenties, working in the UK

My generation is worn out

In many ways I think I am better off than my parents were. I’ve been able to travel and live in different countries. I had more choices than women before me. Where I live, I can love whomever I want to love. I do not have a physical job that wears down my body. But I guess each generation faces different challenges.

My generation is perhaps more likely to be mentally worn out. Housing is less affordable and returns are relatively less certain and I don’t have a pension or a pensions saving account that is protected from double taxation. — Deborah from the Netherlands

Change the voting system

It is probably an unrealistic policy change, but I would like to see some kind of weighting system applied to future voting (be it elections or referendums). The older you are, the fewer years you have left to live and the less you will have to suffer from poor long-term choices.

Brexit is a good example of this. Foolish and impressionable members of the older generation selfishly voted to leave the EU — a decision which will cause long-term damage for my generation well after they are deceased. Older people’s votes should have counted for less in the referendum. — David, working in fintech in London

Introduce a ‘meat licence’

I would introduce a “meat license” which every adult in the UK would require before they purchase/consume meat. To get this license, once a year they would have to go to an abattoir and slaughter a cow or pig. Once they have done this, they are allowed to consume as much meat as they want during the year.

This would encourage others to switch to alternatives that are available or at least reduce meat waste which is a tragically growing issue in the rich world. — Dan, working in London, UK

Replace student fees

Instead of tuition fee loans and maintenance loans I would give all young people a lump sum at regular intervals for their first several years post 18. They could use this towards going to uni, getting training, buying a house, etc. It would help diversify the paths people take post 18 whilst redistributing wealth. — A man in his mid-twenties living in Sheffield, UK

*Comments have been edited for length, style and clarity

Feel free to join the conversation by sharing your thoughts and experiences in the comment section below.

Have you recently graduated? Tell us about the jobs market

The FT wants to hear from graduates and other young people about their experiences of getting their careers off the ground in these uncertain times. Tell us about your experiences via a short survey .

Promoted Content

Explore the series.

Follow the topics in this article

- Lucy Warwick-Ching Add to myFT

- Millennials Add to myFT

- Coronavirus Add to myFT

International Edition

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Parenting & Family Articles & More

How teens today are different from past generations, a psychologist mines big data on teens and finds many ways this generation—the “igens"—is different from boomers, gen xers, and millennials..

Every generation of teens is shaped by the social, political, and economic events of the day. Today’s teenagers are no different—and they’re the first generation whose lives are saturated by mobile technology and social media.

In her new book, psychologist Jean Twenge uses large-scale surveys to draw a detailed portrait of ten qualities that make today’s teens unique and the cultural forces shaping them. Her findings are by turn alarming, informative, surprising, and insightful, making the book— iGen:Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood—and What That Means for the Rest of Us —an important read for anyone interested in teens’ lives.

Who are the iGens?

Twenge names the generation born between 1995 and 2012 “iGens” for their ubiquitous use of the iPhone, their valuing of individualism, their economic context of income inequality, their inclusiveness, and more.

She identifies their unique qualities by analyzing four nationally representative surveys of 11 million teens since the 1960s. Those surveys, which have asked the same questions (and some new ones) of teens year after year, allow comparisons among Boomers, Gen Xers, Millennials, and iGens at exactly the same ages. In addition to identifying cross-generational trends in these surveys, Twenge tests her inferences against her own follow-up surveys, interviews with teens, and findings from smaller experimental studies. Here are just a few of her conclusions.

iGens have poorer emotional health thanks to new media. Twenge finds that new media is making teens more lonely, anxious, and depressed, and is undermining their social skills and even their sleep.

iGens “grew up with cell phones, had an Instagram page before they started high school, and do not remember a time before the Internet,” writes Twenge. They spend five to six hours a day texting, chatting, gaming, web surfing, streaming and sharing videos, and hanging out online. While other observers have equivocated about the impact, Twenge is clear: More than two hours a day raises the risk for serious mental health problems.

She draws these conclusions by showing how the national rise in teen mental health problems mirrors the market penetration of iPhones—both take an upswing around 2012. This is correlational data, but competing explanations like rising academic pressure or the Great Recession don’t seem to explain teens’ mental health issues. And experimental studies suggest that when teens give up Facebook for a period or spend time in nature without their phones, for example, they become happier.

The mental health consequences are especially acute for younger teens, she writes. This makes sense developmentally, since the onset of puberty triggers a cascade of changes in the brain that make teens more emotional and more sensitive to their social world.

Social media use, Twenge explains, means teens are spending less time with their friends in person. At the same time, online content creates unrealistic expectations (about happiness, body image, and more) and more opportunities for feeling left out—which scientists now know has similar effects as physical pain . Girls may be especially vulnerable, since they use social media more, report feeling left out more often than boys, and report twice the rate of cyberbullying as boys do.

Social media is creating an “epidemic of anguish,” Twenge says.

iGens grow up more slowly. iGens also appear more reluctant to grow up. They are more likely than previous generations to hang out with their parents, postpone sex, and decline driver’s licenses.

More on Teens