- UWF Libraries

Literature Review: Conducting & Writing

- Sample Literature Reviews

- Steps for Conducting a Lit Review

- Finding "The Literature"

- Organizing/Writing

- APA Style This link opens in a new window

- Chicago: Notes Bibliography This link opens in a new window

- MLA Style This link opens in a new window

Sample Lit Reviews from Communication Arts

Have an exemplary literature review.

- Literature Review Sample 1

- Literature Review Sample 2

- Literature Review Sample 3

Have you written a stellar literature review you care to share for teaching purposes?

Are you an instructor who has received an exemplary literature review and have permission from the student to post?

Please contact Britt McGowan at [email protected] for inclusion in this guide. All disciplines welcome and encouraged.

- << Previous: MLA Style

- Next: Get Help! >>

- Last Updated: Mar 22, 2024 9:37 AM

- URL: https://libguides.uwf.edu/litreview

Literature Reviews

- General overview of Literature Reviews

- What should a Literature Review include?

- Examples of Literature Reviews

- Research - Getting Started

Online Resources

- CWU Learning Commons: Writing Resources

- Purdue OWL: Writing a Literature Review

Literature Reviews Examples

Social Sciences examples

- Psychology study In this example, the literature review can be found on pages 1086-1089, stopping at the section labeled "Aims and Hypotheses".

- Law and Justice study In this example, the literature review can be found on pages 431-449, stopping at the section labeled "Identifying and Evaluating the Impacts of the Prisoners' Rights Movement". This article uses a historical literature review approach.

- Anthropology study The literature review in this article runs from page 218 at the heading "Between Critique and Enchantment" and ends on page 221 before the heading "The Imagination as a Dimension of Reality".

Hard Science examples

- Physics article The literature review in this paper can be found in the Introduction section, ending at the section titled "Experimental procedure".

- Health Science article The literature review in this article is located at the beginning, before the Methods section.

Arts and Humanities examples

- Composition paper In this example, the literature review has its own dedicated section titled "Literature Review" on pages 2-3.

- Political geography paper The literature review in this paper is located in the introduction section.

Standalone Literature Review examples

- Project-based learning: A review of the literature

- Mental health and gender dysphoria: A review of the literature

- Academic engagement and commercialisation: A review of the literature on university–industry relations

- << Previous: What should a Literature Review include?

- Next: Research - Getting Started >>

- Last Updated: Mar 29, 2024 11:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.lib.cwu.edu/LiteratureReviews

Legal Dissertation: Research and Writing Guide

About this guide, video on choosing a topic, tools on westlaw, lexis and bloomberg, circuit splits, research methodologies, additional methodology resources, conducting a literature review, beginning research, writing style guides, citation guides, ask a librarian.

Ask a librarian:

Reference Hours:

Monday - Friday: 9am-5pm

(812) 855-2938

Q&A Form

About This Page

Choosing a topic can be one of the most challenging aspects of writing an extensive paper. This page has resources to help you find topics and inspiration, before you get started on the in-depth research process.

Related Guides

Citation and Writing Resources

Legal Research Tutorials

Secondary Sources for Legal Research

Methods of Finding Cases

Methods of Finding Statutes

Current Awareness and Alerting Resources

Compiling State Legislative Histories

Locating International and Foreign Law Journals

This guide contains resources to help students researching and writing a legal dissertation or other upper-level writing project. Some of the resources in this guide are directed at researching and writing in general, not specifically on legal topics, but the strategies and tips can still be applied.

The Law Library maintains a number of other guides on related skills and topics that may be of interest:

The Wells Library also maintains guides. A few that may be helpful for managing research can be found here:

Choosing a Topic

This video discusses tips and strategies for choosing a dissertation topic.

Note: this video is not specific to legal dissertation topics, but it may still be of interest as an overview generally.

The Bloomberg/BNA publication United States Law Week can be a helpful resource for tracking down the major legal stories of the day. Log into Bloomberg Law, in the big search box, start typing United States Law Week and the title will appear in the drop down menu beneath the box. This publication provides coverage of top legal news stories, and in-depth "insight" features.

If you have a general idea of the area of law you wish to write about, check out the Practice Centers on Bloomberg. From the homepage, click the Browse link in the top left-hand corner. Then select Practice Centers and look for your area of law. Practice Centers are helpful because they gather cases, statutes, administrative proceedings, news, and more on the selected legal area.

Bloomberg has other news sources available as well. From the homepage, click the Browse link in the top left-hand corner. Then select News and Analysis, then select News or Analysis, and browse the available topics.

If you know what area of law you'd like to write about, you may find the Browse Topics feature in Lexis Advance helpful for narrowing down your topic.

Log into Lexis Advance, click the Browse Topics tab, and select a topic. If you don't see your topic listed, try using the provided search bar to see whether your topic is categorized as a sub-topic within this list.

Once you click on a topic, a box pops up with several options. If you click on Get Topic Document, you'll see results listed in a number of categories, including Cases, Legislation, and more. The News and Legal News categories at the right end of the list may help you identify current developments of interest for your note. Don't forget about the filtering options on the left that will allow you to search within your results, narrow your jurisdiction, and more.

Similar to Lexis Advance, Westlaw Edge has a Topics tab that may be helpful if you know what area of law you'd like to write about.

Log onto Westlaw Edge, and click on the Topics tab. This time, you won't be able to search within this list, so if you're area is not listed, you should either run a regular search from the main search bar at the top or try out some of the topics listed under this tab - once you click on a topic, you can search within its contents.

What is great about the Topics in Westlaw Edge is the Practitioner Insights page you access by clicking on a topic. This is an information portal that allows you quick access to cases, legislation, top news, and more on your selected topic.

In United States federal courts, a circuit split occurs whenever two or more circuit courts of appeals issue conflicting rulings on the same legal question. Circuit splits are ripe for legal analysis and commentary because they present a situation in which federal law is being applied in different ways in different parts of the country, even if the underlying litigants themselves are otherwise similarly situated. The Supreme Court also frequently accepts cases on appeal that involve these types of conflicted rulings from various sister circuits.

To find a circuit split on a topic of interest to you, try searching on Lexis and Westlaw using this method:

in the search box, enter the following: (circuit or court w/s split) AND [insert terms or phrases to narrow the search]

You can also browse for circuit splits on Bloomberg. On the Bloomberg homepage, in the "Law School Success" box, Circuit Splits Charts appear listed under Secondary Sources.

Other sources for circuit splits are American Law Reports (ALR) and American Jurisprudence (AmJur). These publications provide summaries of the law, point out circuit splits, and provide references for further research.

"Blawgs" or law-related blogs are often written by scholars or practitioners in the legal field. Ordinarily covering current events and developments in law, these posts can provide inspiration for note topics. To help you find blawgs on a specific topic, consider perusing the ABA's Blawg Directory or Justia's Blawg Search .

Research Methodology

Types of research methodologies.

There are different types of research methodologies. Methodology refers to the strategy employed in conducting research. The following methodologies are some of the most commonly used in legal and social science research.

Doctrinal legal research methodology, also called "black letter" methodology, focuses on the letter of the law rather than the law in action. Using this method, a researcher composes a descriptive and detailed analysis of legal rules found in primary sources (cases, statutes, or regulations). The purpose of this method is to gather, organize, and describe the law; provide commentary on the sources used; then, identify and describe the underlying theme or system and how each source of law is connected.

Doctrinal methodology is good for areas of law that are largely black letter law, such as contract or property law. Under this approach, the researcher conducts a critical, qualitative analysis of legal materials to support a hypothesis. The researcher must identify specific legal rules, then discuss the legal meaning of the rule, its underlying principles, and decision-making under the rule (whether cases interpreting the rule fit together in a coherent system or not). The researcher must also identify ambiguities and criticisms of the law, and offer solutions. Sources of data in doctrinal research include the rule itself, cases generated under the rule, legislative history where applicable, and commentaries and literature on the rule.

This approach is beneficial by providing a solid structure for crafting a thesis, organizing the paper, and enabling a thorough definition and explanation of the rule. The drawbacks of this approach are that it may be too formalistic, and may lead to oversimplifying the legal doctrine.

Comparative

Comparative legal research methodology involves critical analysis of different bodies of law to examine how the outcome of a legal issue could be different under each set of laws. Comparisons could be made between different jurisdictions, such as comparing analysis of a legal issue under American law and the laws of another country, or researchers may conduct historical comparisons.

When using a comparative approach be sure to define the reasons for choosing this approach, and identify the benefits of comparing laws from different jurisdictions or time periods, such as finding common ground or determining best practices and solutions. The comparative method can be used by a researcher to better understand their home jurisdiction by analyzing how other jurisdictions handle the same issue. This method can also be used as a critical analytical tool to distinguish particular features of a law. The drawback of this method is that it can be difficult to find material from other jurisdictions. Also, researchers should be sure that the comparisons are relevant to the thesis and not just used for description.

This type of research uses data analysis to study legal systems. A detailed guide on empirical methods can be found here . The process of empirical research involves four steps: design the project, collect and code the data, analyze the data, determine best method of presenting the results. The first step, designing the project, is when researchers define their hypothesis and concepts in concrete terms that can be observed. Next, researchers must collect and code the data by determining the possible sources of information and available collection methods, and then putting the data into a format that can be analyzed. When researchers analyze the data, they are comparing the data to their hypothesis. If the overlap between the two is significant, then their hypothesis is confirmed, but if there is little to no overlap, then their hypothesis is incorrect. Analysis involves summarizing the data and drawing inferences. There are two types of statistical inference in empirical research, descriptive and causal. Descriptive inference is close to summary, but the researcher uses the known data from the sample to draw conclusions about the whole population. Causal inference is the difference between two descriptive inferences.

Two main types of empirical legal research are qualitative and quantitative.

Quantitative, or numerical, empirical legal research involves taking information about cases and courts, translating that information into numbers, and then analyzing those numbers with statistical tools.

Qualitative, or non-numerical, empirical legal research involves extracting information from the text of court documents, then interpreting and organizing the text into categories, and using that information to identify patterns.

Drafting The Methodology Section

This is the part of your paper that describes the research methodology, or methodologies if you used more than one. This section will contain a detailed description of how the research was conducted and why it was conducted in that way. First, draft an outline of what you must include in this section and gather the information needed.

Generally, a methodology section will contain the following:

- Statement of research objectives

- Reasons for the research methodology used

- Description and rationale of the data collection tools, sampling techniques, and data sources used, including a description of how the data collection tools were administered

- Discussion of the limitations

- Discussion of the data analysis tools used

Be sure that you have clearly defined the reasoning behind the chosen methodology and sources.

- Legal Reasoning, Research, and Writing for International Graduate Students Nadia E. Nedzel Aspen (2004) A guide to American legal research and the federal system, written for international students. Includes information on the research process, and tips for writing. Located in the Law Library, 3rd Floor: KF 240 .N43 2004.

- Methodologies of Legal Research: Which Kind of Method for What Kind of Discipline? Mark van Hoecke Oxford (2013) This book examines different methods of legal research including doctrinal, comparative, and interdisciplinary. Located at Lilly Law Library, Indianapolis, 2nd Floor: K 235 .M476 2013. IU students may request item via IUCAT.

- An Introduction to Empirical Legal Research Lee Epstein and Andrew D. Martin Oxford University Press (2014) This book includes information on designing research, collecting and coding data, analyzing data, and drafting the final paper. Located at Lilly Law Library, Indianapolis, 2nd Floor: K 85 .E678 2014. IU students may request item via IUCAT.

- Emplirical Legal Studies Blog The ELS blog was created by several law professors, and focuses on using empirical methods in legal research, theory, and scholarship. Search or browse the blog to find entries on methodology, data sources, software, and other tips and techniques.

Literature Review

The literature review provides an examination of existing pieces of research, and serves as a foundation for further research. It allows the researcher to critically evaluate existing scholarship and research practices, and puts the new thesis in context. When conducting a literature review, one should consider the following: who are the leading scholars in the subject area; what has been published on the subject; what factors or subtopics have these scholars identified as important for further examination; what research methods have others used; what were the pros and cons of using those methods; what other theories have been explored.

The literature review should include a description of coverage. The researcher should describe what material was selected and why, and how those selections are relevant to the thesis. Discuss what has been written on the topic and where the thesis fits in the context of existing scholarship. The researcher should evaluate the sources and methodologies used by other researchers, and describe how the thesis different.

The following video gives an overview of conducting a literature review.

Note: this video is not specific to legal literature, however it may be helpful as a general overview.

Not sure where to start? Here are a few suggestions for digging into sources once you have selected a topic.

Research Guides

Research guides are discovery tools, or gateways of information. They pull together lists of sources on a topic. Some guides even offer brief overviews and additional research steps specifically for that topic. Many law libraries offer guides on a variety of subjects. You can locate guides by visiting library websites, such as this Library's site , the Law Library of Congress , or other schools like Georgetown . Some organizations also compile research guides, such as the American Society of International Law . Utilizing a research guide on your topic to generate an introductory source list can save you valuable time.

Secondary Sources

It is often a good idea to begin research with secondary sources. These resources summarize, explain, and analyze the law. They also provide references to primary sources and other secondary sources. This saves you time and effort, and can help you quickly identify major themes under your topic and help you place your thesis in context.

Encyclopedias provide broad coverage of all areas of the law, but do not go in-depth on narrow topics, or discuss differences by jurisdiction, or include all of the pertinent cases. American Jurisprudence ( AmJur ) and Corpus Juris Secundum ( CJS ) have nationwide coverage, while the Indiana Law Encyclopedia focuses on Indiana state law. A number of other states also have their own state-specific encyclopedias.

American Law Reports ( ALR ) are annotations that synopsize various cases on narrow legal topics. Each annotation covers a different topic, and provides a leading or typical case on the topic, plus cases from different jurisdictions that follow different rules, or cases where different facts applying the same rule led to different outcomes. The annotations also refer to other secondary sources.

Legal periodicals include several different types of publications such as law reviews from academic institutions or organizations, bar journals, and commercial journals/newspapers/newsletters. Legal periodicals feature articles that describe the current state of the law and often explore underlying policies. They also critique laws, court decisions, and policies, and often advocate for changes. Articles also discuss emerging issues and notify the profession of new developments. Law reviews can be useful for in-depth coverage on narrow topics, and references to primary and other secondary sources. However, content can become outdated and researchers must be mindful of biases in articles.

Treatises/Hornbooks/Practice Guides are a type of secondary source that provides comprehensive coverage of a legal subject. It could be broad, such as a treatise covering all of contract law, or very narrow such as a treatise focused only on search and seizure cases. These sources are good when you have some general background on the topic, but you need more in-depth coverage of the legal rules and policies. Treatises are generally well organized, and provide you with finding aids (index, table of contents, etc.) and extensive footnotes or endnotes that will lead you to primary sources like cases, statutes, and regulations. They may also include appendices with supporting material like forms. However, treatises may not be updated as frequently as other sources and may not cover your specific issue or jurisdiction.

Citation and Writing Style

- Legal Writing in Plain English Bryan A. Garner University of Chicago Press, 2001. Call # KF 250 .G373 2001 Location: Law Library, 3rd Floor Provides lawyers, judges, paralegals, law students, and legal scholars with sound advice and practical tools for improving their written work. The leading guide to clear writing in the field, this book offers valuable insights into the writing process: how to organize ideas, create and refine prose, and improve editing skills. This guide uses real-life writing samples that Garner has gathered through decades of teaching experience. Includes sets of basic, intermediate, and advanced exercises in each section.

- The Elements of Legal Style Bryan A. Garner Oxford University Press, 2002. Call # KF 250 .G37 2002 Location: Law Library, 1st Floor, Reference This book explains the full range of what legal writers need to know: mechanics, word choice, structure, and rhetoric, as well as all the special conventions that legal writers should follow in using headings, defined terms, quotations, and many other devices. Garner also provides examples from highly regarded legal writers, including Oliver Wendell Holmes, Clarence Darrow, Frank Easterbrook, and Antonin Scalia.

- Grammarly Blog Blog featuring helpful information about quirks of the English language, for example when to use "affect" or "effect" and other tips. Use the search feature to locate an article relevant to your grammar query.

- Plain English for Lawyers Richard C. Wydick Carolina Academic Press, 2005. Call # KF 250 .W9 2005 Location: Law Library, 3rd Floor Award-winning book that contains guidance to improve the writing of lawyers and law students and to promote the modern trend toward a clear, plain style of legal writing. Includes exercises at the end of each chapter.

- The Chicago Manual of Style University of Chicago Press, 2010. Call # Z 253 .U69 2010 Location: Law Library, 2nd Floor While not addressing legal writing specifically, The Chicago Manual of Style is one of the most widely used and respected style guides in the United States. It focuses on American English and deals with aspects of editorial practice, including grammar and usage, as well as document preparation and formatting.

- The Chicago Manual of Style (Online) Bryan A. Garner and William S. Strong The University of Chicago Press, 2017. Online edition: use the link above to view record in IUCAT, then click the Access link (for IU students only).

- The Bluebook Compiled by the editors of the Columbia Law Review, the Harvard Law Review, the University of Pennsylvania Law Review, and the Yale Law Journal. Harvard Law Review Association, 2015. Call # KF245 .B58 2015 Location: Law Library, 1st Floor, Circulation Desk The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation is a style guide that prescribes the most widely used legal citation system in the United States. The Bluebook is taught and used at a majority of U.S. law schools, law reviews and journals, and used in a majority of U.S. federal courts.

- User's Guide to the Bluebook Alan L. Dworsky William S. Hein & Co., Inc., 2015. Call # KF 245 .D853 2015 Location: Law Library, Circulation Desk "This User's Guide is written for practitioners (law students, law clerks, lawyers, legal secretaries and paralegals), and is designed to make the task of mastering citation form as easy and painless as possible. To help alleviate the obstacles faced when using proper citation form, this text is set up as a how-to manual with a step-by-step approach to learning the basic skills of citation and includes the numbers of the relevant Bluebook rules under most chapter subheadings for easy reference when more information is needed"--Provided by the publisher.

- Legal Citation in a Nutshell Larry L. Teply West Academic Publishing, 2016. Call # KF 245 .T47 2016 Location: Law Library, 1st Floor, Circulation Desk This book is designed to ease the task of learning legal citation. It initially focuses on conventions that underlie all accepted forms and systems of legal citation. Building on that understanding and an explanation of the “process” of using citations in legal writing, the book then discusses and illustrates the basic rules.

- Introduction to Basic Legal Citation (Online) Peter W. Martin Cornell Legal Information Institute, 2017. Free online resource. Includes a thorough review of the relevant rules of appellate practice of federal and state courts. It takes account of the latest edition of The Bluebook, published in 2015, and provides a correlation table between this free online citation guide and the Bluebook.

- Last Updated: Oct 24, 2019 11:00 AM

- URL: https://law.indiana.libguides.com/dissertationguide

Writing in Criminal Justice: Writing a Literature Review

- SSC 215: Home

- How to search library databases

- How to find books

- How to find articles

- Should I Trust Internet Sources?

- What Is A Peer-Reviewed Article?

- Writing a Literature Review

- Citing Sources

- Finding Books

- Finding Articles

- Selected Online Resources for SSC215

- Experimental (Empirical) Studies

- Library Research Guides

Development of a Literature Review

Keep some steps in mind when beginning your work on a literature review:

- What is my thesis? What is the central idea I am trying to prove to my reader?

- What materials should I look at? Remember a literature review is a focused look at a limited amount of material. You do not have to examine every article ever written on your topic.

- Do the materials I have chosen to write on really help to focus the reader to understand the topic I am writing about

Writing a Literature Review: Step by Step

Literature Reviews: An Overview

Tips for Writing a Literature Review

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review is an overview of literature published on a topic, issue, or theory. It can cover a wide variety of materials including but not limited to scholarly articles, books, dissertations, reports, conference proceedings, etc. The purpose of a literature review is to describe, summarize, and evaluate the works being examined for the review.

How you construct a literature review and the specific outline of it can vary depending on what your professor has laid out for you in your assignment. The review can be just a summary of sources on the subject you are writing about or it could be an examination of the material on your chosen topic. It can also be an analysis of previous research in an in-depth manner or just trace the development of a field of study over time. A good literature review should ultimately be a guide for its audience, giving them a solid idea about what extent and limits of the research has been done so far.

Structure of a Literature Review

When writing a literature review, consider first what it is you want to write about. Your topic summarized in one sentence is your thesis . Next you should think about how you want to organize your material. What is the most important thing you want to get across in your presentation of resources?

The most basic organization of a literature review is to put it together like a general academic paper with an Introduction , Body , and Conclusion – a beginning where you lay out to the reader what you are doing, a middle where you discuss the literature in question, and an ending where you sum up what you have been trying to prove. Another way to organize your paper is by theme or method or chronology .

- A paper organized by theme deals with sources that focus on a specific topic or issue. For example a review by theme may deal with police with one section on one police department and a second on a different police department. But all the sources ultimately deal with the same topic, in this case the police.

- A review organized by method looks at the methods the original researcher used in writing the literature you are reviewing. A review by method may group literature such as case studies in one section and interviews in another.

- And a chronological organization looks at the literature by when it was written. A chronological review would look at material in the form of a timeline such as debates on a subject that happened in one year followed by a debate on the same subject at a later date.

A third way to organize your paper is by author or philosophy .

- A review organized by author usually focuses on prominent researchers in the field you are examining. For instance if you were writing about physics, you could group your articles by prominent physicists such as articles by Isaac Newton and his findings and materials by Albert Einstein and his findings.

- A review organized by philosophy looks at the argument being made in the materials under examination. For instance if one group of articles is about capitalism and another group is about communism, you may want to group them by what the article is trying to prove than by who wrote it or when it was written.

Keep This in Mind

When you begin to work on your literature review, keep in mind the following ideas:

- What question and/or problem are you trying to answer? What is the thesis you are trying to prove?

- Are you being specific about your topic? Is it too broad? And if it is can you narrow it down?

- What does the literature say about your topic? Is there agreement or disagreement on the subject?

- << Previous: What Is A Peer-Reviewed Article?

- Next: Citing Sources >>

- Last Updated: Sep 27, 2023 2:25 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/SSC215

- A-Z Databases

- Training Calendar

- Research Portal

Law: Introduction to Research

- Finding a Research Topic

- Getting Started

- Generate Research Ideas

- Brainstorming

- Scanning Material

- Suitability Analysis

- The difference between a topic and a research question

Literature Review

- Referencing

When thinking about any risks associated with your research you may realise that it is difficult to predict your research needs and the accompanying risks as you were not sure what information would be required; this is why a literature review is necessary. A thorough literature review will help identify gaps in existing knowledge where research is needed; filling those gaps is one of the prime functions of research. The literature review will indicate what is known about your chosen area of research and show where further contributions from further research can be made.

Undertaking a literature review is probably one of the most difficult stages of the research process but it can be both exciting and fulfilling. This section aims to put the literature review into context and to explain what it does and how to do it.

The literature on a particular legal topic is of fundamental importance to the international community of researchers and scholars working within particular academic disciplines. Academic publishing supports research by enabling researchers to tell the world what they have discovered and allows others researching in the same area to peer review their work; in this way, a combined body of knowledge is established.

During your research, you will use the literature to:

- develop your knowledge of your chosen topic and the research process in general terms

- ensure that you have an understanding of the current state of academic knowledge within your chosen topic

- identify the gaps in knowledge that your research will address

- ensure that your research question will not become too broad or narrow.

The Purpose of Literature Review

Understanding existing research is at the core of your study. A good literature review is important because it enables you to understand the existing work in your chosen topic as well as explaining concepts, approaches and ideas relevant to that topic.

The literature review is also essential as it will enable you to identify an appropriate research method. Your research method, and needs, can only be established in the light of a review of existing knowledge.

Your literature review is regarded as secondary research. The research process is an ongoing one, so your literature review is never really finished or entirely up to date as reading and understanding the existing literature is a constant part of being a researcher; professionally it is an obligation.

Different Types of Research

- Different types of research

- Different sources

- Understand research in your chosen area

- Explaining relevant concepts and ideas

- Contextualizing your results

- What to read?

- Peer review

- Searching the literature

- Critically evaluating documents

Your research will draw upon both primary and secondary research. The difference between primary and secondary research is that primary research is new research on a topic that adds to the existing body of knowledge. Secondary research is research into what others have written or said on the topic.

You will also draw upon primary and secondary sources to undertake your research. Primary sources are evidence recorded at the time, such as a photograph, an artifact, a diary, or the text of a statute or court ruling. Primary legal sources are the products of those bodies with the authority to make, interpret and apply the law. Secondary sources are what others have written or said about the primary source, their interpretation, support, or critique of the primary source. Similarly, secondary legal sources are what academics, lawyers, politicians, journalists, and others have said or written about a primary legal source.

Part of the aim of your studies is to make a contribution to the existing body of academic knowledge. Without a literature review there would be a risk that what you are producing is not actually newly researched knowledge; instead it may only be a replication of what is already known. The only way to ensure that your research is new is to find out what others have already done. However, this is not to say that you should never attempt to research some things that have been done before if you feel that you can provide valuable new insights.

You also need to use the literature review to build a body of useful ideas to help you conceptualise your research question and understand the current thinking on the topic. By studying the literature you will become familiar with research methods appropriate to your chosen topic and this will show you how to apply them. Careful consideration should be given to the research methods deployed by existing researchers in the topic, but this should not stifle innovative approaches. Your literature study should also demonstrate the context of your own work, and how it relates, and builds, on the work of others; ‘to make proper acknowledgment of the work of previous authors and to delineate [your] own contributions to the field’ (Sharp et al., 2002, p. 28).

When you have completed your primary research, you will still have the task of demonstrating how your research contributes to the topic in which you have been working. Comparing your results to similar work within the topic will demonstrate how you have moved the discipline forward.

Comparing your results with the gaps that you identified in the early stages of your literature review will allow you to evaluate how well you have addressed them.

A successful literature review will have references from a number of different types of sources; it is not simply a book review. What is much more important than the number of references is that you have a selection of literature that is appropriate for your research; what is appropriate will depend on the type of research you are undertaking. For example, if your topic is in an area of recent legal debate, you will probably find most of the relevant material in journal articles or conference papers. If you are studying policy issues in law-making, you would expect to cite more government reports. In either case, you will need some core references that are recent and relevant. A research project could also contain a number of older citations to provide a historical context or describe established methods. Perhaps a recent newspaper, journal or magazine article could illustrate the contemporary relevance or importance of your research.

You will have to use your own judgment (and the advice of your tutor) to ascertain what the suitable range of literature and references is for your review. This will differ for each topic of research, but you will be able to get a feel for what is appropriate by looking at relevant publications; most publications fall into the following broad categories:

Online legal databases

Online legal research services such as Westlaw , LexisNexis , JSTOR , EBSCOhost , or HeinOnline are a good source of journal articles and as a repository of legislation, case law, law reports, newspaper and magazine articles, public records, and treatises.

Journal articles

These provide more recent discussions than textbooks. Peer-reviewed journals are the gold standard for academic quality. Having at least some journal articles in your literature review is almost always required. Note that the lead time on journal articles is often up to two years, so they may not be sufficiently up to date for fast-moving areas. Look for special issues of journals, as these usually focus on a particular topic and you may find that they are more relevant to your area of research.

Many law schools host journals that contain articles by academics and students; these may also be of interest. Other sources could include online newspapers such as The Conversation which are sourced from academia and designed to highlight current academic research or respond to current events.

Conference literature

Academic conferences are meetings in which groups of academics working in a particular area meet to discuss their work. Delegates usually write one or more papers that are then collected into a volume or special edition of a journal. Conference proceedings can be quite good in providing a snapshot of a topic, as they tend to be quite focused. Looking at the authors of the papers can also give you an idea of who the key names in that area are. The quality varies widely, both in terms of the material published and how it is presented. Most conferences include some professional researchers, some of whom can be contacted, and lots of students. Conference papers are often refereed but usually not to the same level as journal articles.

Having conference papers in your literature review does lend academic credibility, especially in rapidly developing areas, and conference papers generally contain the preliminary work that eventually forms journal articles.

Textbooks are good for identifying established, well-understood concepts and techniques, but are unlikely to have enough up-to-date research to be the main source of literature. Most disciplines, however, have a collection of canonical reference works that you should use to ensure you are implementing standard terms or techniques correctly. Textbooks can also be useful as a starting point for your literature search as you can investigate journal articles or conference papers that have been cited. Footnotes are a rich source of preliminary leads.

Law magazines

These can be useful, particularly for projects related to the role of lawyers. Be aware of the possibility of law firm bias (for example in labour law towards employers, employee rights, or trade unions) or articles that are little more than advertisements. Examples of professional journals include the SA ePublications (Sabinet), De Rebus - SA Attorneys' Journal , etc . Most jurisdictions have some form of a professional journal.

Government and other official reports

There is a wide range of publications, including ‘white papers', official reports, census, and other government-produced statistical data that are potentially useful to the researcher. Be aware of the possibility of political or economic bias or the reflection of a situation that has since changed.

Internal company or organisation reports/Institutional repository

These may be useful in a few situations but should be used sparingly, particularly if they are not readily available to the wider community of researchers. They will also not have been through a process of academic review. Such unpublished or semi-published reports are collectively called ‘grey literature.

Manuals and handbooks

These are of limited relevance, but may be useful to establish current techniques, approaches, and procedures.

Specialist supplements from quality newspapers can provide useful up-to-date information, as can the online versions of the same papers. Some newspapers provide a searchable archive that can provide a more general interest context for your work.

The worldwide web

This is widely used by lawyers today. According to the 2011 American Bar Association Report, 84.4% of attorneys turn to online sources as their first step in legal research (Lenhart, 2012, p. 27). It is an extremely useful source of references, particularly whilst carrying out an initial investigation. Although sites such as Wikipedia can be very helpful for providing a quick overview of particular topics and highlighting other areas of research that may be connected to your own, they should not usually be included in your review as they are of variable quality and are open to very rapid change. Treat the information you find on the internet with appropriate care. Be very careful about the source of information and look carefully at who operates the website.

Personal communications

Personal communications such as (unpublished) letters and conversations are not references. If you use such comments (and of course, you should respect the confidence of anyone you have discussed your work with), you should draw attention to the fact that you are quoting someone and mark it as ‘personal communication’ in the body of the text. Responses you might obtain from, for example, interviews and questionnaires as part of your research should be reported as data obtained through primary research.

It is crucial that most of your literature should come from peer-reviewed materials, such as journal articles. The point of peer reviewing is to increase quality by ensuring that the ideas presented seem well-founded to other experts in the topic. Conference papers are generally peer-reviewed, although the review process is usually less stringent, and so the standing of conference papers is not the same as for journals. Books, magazines, newspapers, and websites (including blogs, wikis, corporate sites, etc.) are not subject to peer review, and you should treat them with appropriate caution. Also, treat each publication on its merits; it is more helpful to use a good conference paper than a poor journal paper. Similarly, it is acceptable to refer to a well-written blog by a knowledgeable and well-known author provided that you supply appropriate context. In all these cases, the important thing is that you interpret the work correctly.

You will have undertaken legal research and developed your research skills as you prepared for earlier assignments. A literature review builds on this. You may, however, be wondering where to start. One technique is to use an iteration of five stages to help you with your early research.

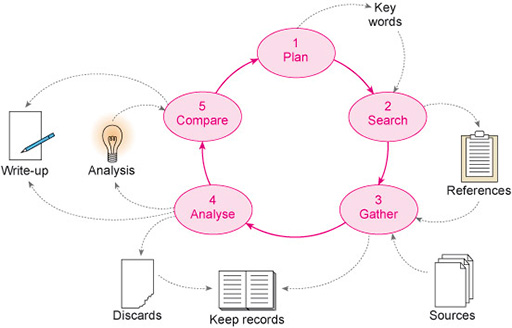

The five stages are: planning, searching, gathering, analysing and comparing.

Following these stages will provide you with a systematic approach to gathering and analysing literature in your chosen topic of study; this will ensure that you take a critical approach to the literature.

To undertake an effective review of the literature on your chosen topic you will need to plan your review carefully. This includes setting aside enough time in which to undertake your review. In planning there are several aspects you need to think about:

- What sources of information are most relevant to your chosen research question?

- What gaps in knowledge have you identified in your chosen topic and used as a basis for your research question?

- What search terms will you use and how will you refine these?

- How will you record your sources?

- How will you interrogate those sources?

- How will you continue to review the literature as you progress with your research in order to keep as up-to-date as possible?

- Are you able to easily access all the sources you need?

- What arrangements may you need to make to access any hard copy materials?

- Will you join one of the legal alert services to keep you abreast of changes in your chosen topic (such as new court judgments)?

- What notes of progress will you record in your research diary?

Spending time thinking about all aspects of the literature review, planning your time, and setting yourself targets will help to keep your research on track and will enable you to record your progress and any adjustments you make, along with the reasons for those adjustments.

This section is designed to provide you with some reminders in relation to searching, choosing search terms and some ideas about where to start in undertaking a literature review.

Where to start

The best places to start are likely to be a legal database (or law library) and Google Scholar. Many students and academics now use Google Scholar as one of their ‘go to’ tools for scholarly research. It can be helpful to gain an overview of a topic or to gain a sense of direction, but it is not a substitute for your own research of primary and secondary sources.

Having gained an overview from your initial search through browsing general collections of documents, you will then need to undertake a more detailed search to find specific documents. Identifying relevant scholarly articles and following links in footnotes and bibliographies can be helpful as you continue your search for relevant information.

One of the decisions you will have to make is when to stop working on your literature review and your research, and when to start writing up your dissertation. This will be determined by the material you gather and the time constraints you are working on.

Selecting resources

One starting point may be to locate a small number of key journal papers or articles; for a draft outline proposal for your research, you might have around four to six of these, accumulating more as you develop the research subsequently. Aim for quality, not quantity. Look for relevant and recent publications. Most of your references will typically not be more than four years old, although this does depend on your field of study. You will need quite a few more in due course to cover other aspects of your research such as methods and evaluation, but at this stage, you need only a few recent items.

While reading these documents, aim to identify the key issues that are essential to your research question, ideally around four to six.

Compare and contrast the literature, looking for commonalities, agreements, and disagreements and for problem identification and possible answers. Then write up your analysis of the comparison and any conclusions you might reach. The required outcome will be that you can make an informed decision about how to proceed with your primary research, based on the work carried out by other researchers.

Note that ultimately there are no infallible means of assessing the value of a given reference. Its source may be a useful indication, but you have to use your judgment about its value for your research.

Reviewing your sources

Skim read each document to decide whether a book or paper is worth reading in more depth. To do this you need to make use of the various signposts that are available from the:

- notes on a book’s cover can help situate the content

- abstract (for a paper), or the preface (for a book)

- contents page

- introduction

- conclusions

- references section (sometimes called the ‘bibliography’)

In your record, make a brief note (one or two sentences) of the main points.

Next, skim through the opening page of each chapter, or the first paragraph of each section. This should give you enough information to assess whether you need to read the book or paper in more depth, again make a suitable note against that record.

Reading in more detail: SQ3R

If you have decided to look in more detail at a source document that you have to skim read, you can use the well-known ‘SQ3R’ approach (Skimming, Questioning, Reading, Recalling, and Reviewing).

1. Skimming – skim reading the chapter or part of the paper that relates to your topic, or otherwise interests you.

2. Questioning – develop a few questions that you consider the text might answer for you. You can often use journal, chapter, or section titles to help you formulate relevant questions. For example, when studying a journal article with the title, ‘Me and my body: the relevance of the distinction for the difference between withdrawing life support and euthanasia’, you might ask, ‘How is the distinction between withdrawing life support and euthanasia drawn?’

3. Reading – read through the chapter, section, or paper with your questions in mind. Do not make notes at this stage.

4. Recalling – make notes on what you have read. You should normally develop your own summary or answers to your questions. There will also be short passages that you may want to note fully, perhaps to use as a quotation for when you write up your literature review. Be sure to note carefully the page(s) on which the quotation appears.

5. Reviewing – check through the process, perhaps flicking through the section or article again. It is also worth emphasising that if you maintain your reference list as you go along, not only will you save yourself a lot of work in later stages of the research, but you will also have all the necessary details to hand for writing up with fewer mistakes.

(adapted from Blaxter et al., 1996, p. 114)

There is no doubt that this approach takes considerably more effort than sitting back and studying a text passively. The benefit from the extra work involved in the development of a critical approach, which you must adopt for your research.

Following citations in a paper

When you have found (and read) your first couple of papers, you can then use them to seed your search for other useful literature. In this case, we will use this example:

When we looked at the references list in Suppon, J. F. (2010) ‘Life after death: the need to address the legal status of posthumously conceived children', Family Court Review , vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 228–45, a couple of items, going only by the titles, looked promising:

- Doucettperry, Major M. (2008) ‘To Be Continued: A Look at Posthumous Reproduction As It Relates to Today’s Military’, The Army Lawyer , no. 420, pp. 1–22.

- Karlin, J. H. (2006) ‘“Daddy, Can you Spare a Dime?”: Intestate Heir Rights of Posthumously Conceived Children’, Temple Law Review , vol. 79, no. 4, pp. 1317–54.

These are simply the papers that we felt looked most appropriate from the references. There is no formula for determining the best paper; you simply need to read a few and try to develop a feel for which seem the most appropriate for your own research project. You should only be citing papers that contribute to your research in a significant way, or that you have included material from; not everything that you read (and discarded) along the way.

Recording your references

We strongly suggest that you establish a recording system at the outset when you begin your research and keep maintaining records in an organised and complete manner as you progress. You need to choose a consistent method of recording your references; this is a personal choice and can be paper-based or electronic. Do not be tempted to have more than one method or repository as this can lead to confusion and unnecessary extra work. There are software tools available that can help you to both organise your references and incorporate them into your written work. Always keep a backup copy of your records.

The following is a suggestion as to how you might record any document that you think you may use.

Open a new record, and record the basic details:

- author(s), including initials

- date of publication

- title of work or article.

Additionally, for books:

- place of publication

- page numbers of relevant material.

Additionally, for journal papers:

- journal name

- volume and issue number

- page range of the whole article.

‘How many references are needed to make a good literature review?’ There is no straightforward answer to this. In general, an appropriate number of references would be in the range of 15 to 25, with around 20 being typical. However, this is not hard and fast and will depend on the topic and research question chosen.

The crucial thing is to aim for quality and relevance ; there is no credit to be gained from amassing a lengthy list of material, even if it all appears to be relevant. Part of your task is to select a range of references that is appropriate for the length and scope of your research project. It is easier, and more conducive to good research, to handle a smaller number of references specifically chosen to support your argument. Remember also that in general, a student whose research project contained a smaller number of references would generally be expected to demonstrate a deeper and more critical understanding of those references.

A colleague once commented on a student’s work in the following vein: ‘I don’t really need you to tell me what the author thinks since I can read her thoughts myself, but I do want to know what you think about what the author thinks’. Literature reviews are not a description of what has been written by other people in a particular field, they should be a discussion of what you think of what they have written, and how it helps clarify your own thinking.

This is why critical judgement is so important for your literature review. You must exercise critical judgement when determining which sources to read in-depth, and when evaluating the argument they put forward. Finally, critical judgement is important in communicating how those arguments might frame your research. It should not be a narrative of what you have read and the stories those sources tell. It should be sparing in its description of others’ arguments, and expansive in how those arguments have shaped your own thinking.

You need to exercise critical judgement as to which resources are the most useful and worthy of discussion. Having done this, you also need to ensure that your review is analytical rather than descriptive. A critical review extracts elements from the resource that directly relate to the chosen research interest; it debates them, or compares and contrasts them with how other resources have analysed them. A critical examination of the literature should allow you to develop your understanding of your research question. It should guide you to what knowledge you will need to answer your research question, and begin to develop some subsidiary questions. This will break the content down into more manageable and achievable segments of knowledge that you require.

Some elements of a good critical literature review are:

- relating different writings to each other, indicating their differences and contradictions, and highlighting what they lack

- understanding the values and theories that inform, and colour, reading and writing

- viewing research writing as an environment of contested views and positions

- placing the material in the context of your own research.

An excellent way to critically analyse a document is to use the PROMPT system. The PROMPT system indicates what factors you should consider when evaluating a document. PROMPT stands for:

- Presentation – is the publication easy to read?

- Relevance – how will the publication help address your research aim?

- Objectivity – what is the balance between evidence and opinion? Does the evidence seem balanced? How was the research funded?

- Method – was the research in the publication carried out appropriately?

- Provenance – who is the author and how was the document published?

- Timeliness – is the publication still relevant, or has it been superseded?

By thinking about each of these factors when you read a publication in-depth, you will be able to provide a deeper, more critical analysis of each publication. A final tip for critical reading is to note down your overall impressions and any questions you still have at the end. Keeping a list of such open questions can help you identify the gaps in the literature by noticing which questions were raised, but not answered, by the publication; this, in turn, will guide your research.

In the planning stage, you thought about the gaps in existing knowledge you had identified, and which you then used as a basis to develop your research question. Through the work, you undertook in the earlier stages of your literature review you have a clear understanding of the existing work within the topic. At this point, a comparison of the results of your literature review, with the gaps you had previously identified, will enable you to reflect, and consider, whether you now have enough knowledge to address those gaps. You can then evaluate whether you need to further refine your literature review.

- << Previous: The difference between a topic and a research question

- Next: Referencing >>

- Last Updated: Sep 10, 2023 9:54 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uwc.ac.za/c.php?g=1159497

UWC LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICES

leiden lawmethods portal

Systematic literature review.

Last update: December 10, 2020

‘Literature review’ can refer to a portion of a research article in which the author(s) describe(s) or summarizes a body of literature which is relevant to their article. ‘Literature review’ can also refer to a methodological approach in which a selection of existing literature is collected and analyzed in order to answer a specific question. One approach to doing this type of literature review is called a ‘systematic literature review’ (SLR).

When conducting an SLR, the researcher creates a set of rules or guidelines prior to beginning the review. These rules determine the characteristics of the literature to be included and the steps to be followed during the research process. Creating these rules helps the researcher by narrowing down the focus of their project and the scope of the literature to be included, and they aid in making the research methodology transparent and replicable.

There are many different ways that an SLR can be used in socio-legal research. For example, an SLR can be used to show the impact of a certain law or policy (Loong e.a. 2019), uncover patterns across literature (e.g. perpetrator characteristics) (Alleyne & Parfitt 2017), outline crime prevention strategies that are currently in place (Gorden & Buchanan 2013), describe to what extent a problem is understood or researched (Krieger 2013), point out the gaps in the current research (Urinboyev e.a. 2016), or identify potential areas for future research. Various types of documents may be included in an SLR such as court transcripts, academic literature, news articles, NGO reports or government documents.

The first step for starting your SLR is creating a research journal in which you will write down your SLR rules and keep track of your daily activities. This will help you keep a timeline of your project, keep track of your decision making process, and maintain the transparency and replicability of your research. The next step is determining your research question. When you have your research question, you can create the inclusion and exclusion criteria or the characteristics that literature must or must not have to be included in your SLR. The key question is “what kind of information is needed to answer the research question?” It is necessary to explain why the criteria were selected. After this, you can begin searching for and collecting literature which meets your inclusion criteria. Different databases and sources of literature (e.g. academic journals or newspapers) will yield different search results, so it may be helpful to do trial searches to see which sources provide the most relevant literature for your project. Once you have collected all of your literature, you can begin reading and analyzing the literature.

There are various research tools that can aid you in conducting your SLR such as qualitative data analysis software (e.g. ATLAS.ti) or reference manager software (e.g. Mendeley). Determine which programs to use based on your personal preference and your research project.

Fink, A. (2014). Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

Hagen-Zanker, J. & Mallet, R. (2013). How to do a Rigorous, Evidence Focused Literature Review in International Development: A Guidance Note. Working paper Overseas Direct Investment.

Oliver, S., & Sutcliffe, K. (2012). Describing and analysing studies. Gough, D. A. & Oliver, S. In An Introduction to Systematic Reviews. London, UK. SAGE.

Pittaway, L. (2008). Systematic Literature Reviews. Thorpe, R. & Holt, R. In T he Sage Dictionary of Qualitative Management Research . London, UK. SAGE.

Siddaway, A. (2014). What Is a Systematic Literature Review and How Do I Do One?

Snel, M. & de Moraes, J. (2018). Doing a Systematic Literature Review in Legal Scholarship. The Hague, NL. Eleven International Publishing.

Interactive Learning Module 1: Introduction to Conducting Systematic Reviews

Alleyne, E. & Parfitt, C. (2017). Adult-Perpetrated Animal Abuse: A Systematic Literature Review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. Vol. 20. No. 3. Pp. 344-357.

Example of a systematic literature review.

Brown, R. T. (2010). Systematic Review of the Impact of Adult Drug-Treatment Courts. Translational Research . Vol. 155. No 6. Pp. 263-274.

Gorden, C., & Buchanan, J. (2013). A Systematic Literature Review of Doorstep Crime: Are the Crime-Prevention Strategies More Harmful than the Crime? The Howard Journal . Vol. 52. No. 5. Pp. 498-515.

Krieger, M. A. (2016). Unpacking “Sexting”: A Systematic Review of Nonconensual Sexting in Legal, Educational, and Psychological Literatures. Trauma, Violence & Abuse . Vol. 18. No. 5. Pp. 593-601.

Loong, D., Bonato, S., Barnsley, J., & Dewa, C. S. (2019). The Effectiveness of Mental Health Courts in Reducing Recidivism and Police Contact: A Systematic Review. Community Mental Health Journal. Vol. 55. No. 7 Pp. 1073-1098.

Urinboyev, R., Wickenberg, P., & Leo, U. (2016). Child Rights, Classroom, and Social Management: A Systematic Literature Review. The International Journal of Children’s Rights. Vol. 24. No. 3. Pp. 522-547.

University Library

- Research Guides

Criminology & Criminal Justice

- Literature Reviews

- Getting Started

- News, Newspapers, and Current Events

- Books and Media

- Journals, Databases, and Collections

- Data and Statistics

- Careers and Career Resources for Criminology and Social Justice Majors

- Annotated Bibliographies

- APA 6th Edition

What is a Literature Review?

The scholarly conversation.

A literature review provides an overview of previous research on a topic that critically evaluates, classifies, and compares what has already been published on a particular topic. It allows the author to synthesize and place into context the research and scholarly literature relevant to the topic. It helps map the different approaches to a given question and reveals patterns. It forms the foundation for the author’s subsequent research and justifies the significance of the new investigation.

A literature review can be a short introductory section of a research article or a report or policy paper that focuses on recent research. Or, in the case of dissertations, theses, and review articles, it can be an extensive review of all relevant research.

- The format is usually a bibliographic essay; sources are briefly cited within the body of the essay, with full bibliographic citations at the end.

- The introduction should define the topic and set the context for the literature review. It will include the author's perspective or point of view on the topic, how they have defined the scope of the topic (including what's not included), and how the review will be organized. It can point out overall trends, conflicts in methodology or conclusions, and gaps in the research.

- In the body of the review, the author should organize the research into major topics and subtopics. These groupings may be by subject, (e.g., globalization of clothing manufacturing), type of research (e.g., case studies), methodology (e.g., qualitative), genre, chronology, or other common characteristics. Within these groups, the author can then discuss the merits of each article and analyze and compare the importance of each article to similar ones.

- The conclusion will summarize the main findings, make clear how this review of the literature supports (or not) the research to follow, and may point the direction for further research.

- The list of references will include full citations for all of the items mentioned in the literature review.

Key Questions for a Literature Review

A literature review should try to answer questions such as

- Who are the key researchers on this topic?

- What has been the focus of the research efforts so far and what is the current status?

- How have certain studies built on prior studies? Where are the connections? Are there new interpretations of the research?

- Have there been any controversies or debate about the research? Is there consensus? Are there any contradictions?

- Which areas have been identified as needing further research? Have any pathways been suggested?

- How will your topic uniquely contribute to this body of knowledge?

- Which methodologies have researchers used and which appear to be the most productive?

- What sources of information or data were identified that might be useful to you?

- How does your particular topic fit into the larger context of what has already been done?

- How has the research that has already been done help frame your current investigation ?

Examples of Literature Reviews

Example of a literature review at the beginning of an article: Forbes, C. C., Blanchard, C. M., Mummery, W. K., & Courneya, K. S. (2015, March). Prevalence and correlates of strength exercise among breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors . Oncology Nursing Forum, 42(2), 118+. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com.sonoma.idm.oclc.org/ps/i.do?p=HRCA&sw=w&u=sonomacsu&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CA422059606&asid=27e45873fddc413ac1bebbc129f7649c Example of a comprehensive review of the literature: Wilson, J. L. (2016). An exploration of bullying behaviours in nursing: a review of the literature. British Journal Of Nursing , 25 (6), 303-306. For additional examples, see:

Galvan, J., Galvan, M., & ProQuest. (2017). Writing literature reviews: A guide for students of the social and behavioral sciences (Seventh ed.). [Electronic book]

Pan, M., & Lopez, M. (2008). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (3rd ed.). Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Pub. [ Q180.55.E9 P36 2008]

Useful Links

- Write a Literature Review (UCSC)

- Literature Reviews (Purdue)

- Literature Reviews: overview (UNC)

- Review of Literature (UW-Madison)

Evidence Matrix for Literature Reviews

The Evidence Matrix can help you organize your research before writing your lit review. Use it to identify patterns and commonalities in the articles you have found--similar methodologies ? common theoretical frameworks ? It helps you make sure that all your major concepts covered. It also helps you see how your research fits into the context of the overall topic.

- Evidence Matrix Special thanks to Dr. Cindy Stearns, SSU Sociology Dept, for permission to use this Matrix as an example.

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliographies

- Next: ASA style >>

- Last Updated: Jan 17, 2024 12:31 PM

- URL: https://libguides.sonoma.edu/CCJS

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

Published on 22 February 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 7 June 2022.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research.

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarise sources – it analyses, synthesises, and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why write a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1: search for relevant literature, step 2: evaluate and select sources, step 3: identify themes, debates and gaps, step 4: outline your literature review’s structure, step 5: write your literature review, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a dissertation or thesis, you will have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position yourself in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your dissertation addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

You might also have to write a literature review as a stand-alone assignment. In this case, the purpose is to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of scholarly debates around a topic.

The content will look slightly different in each case, but the process of conducting a literature review follows the same steps. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research objectives and questions .

If you are writing a literature review as a stand-alone assignment, you will have to choose a focus and develop a central question to direct your search. Unlike a dissertation research question, this question has to be answerable without collecting original data. You should be able to answer it based only on a review of existing publications.

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research topic. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list if you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can use boolean operators to help narrow down your search:

Read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

To identify the most important publications on your topic, take note of recurring citations. If the same authors, books or articles keep appearing in your reading, make sure to seek them out.

You probably won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on the topic – you’ll have to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your questions.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models and methods? Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- How does the publication contribute to your understanding of the topic? What are its key insights and arguments?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible, and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can find out how many times an article has been cited on Google Scholar – a high citation count means the article has been influential in the field, and should certainly be included in your literature review.

The scope of your review will depend on your topic and discipline: in the sciences you usually only review recent literature, but in the humanities you might take a long historical perspective (for example, to trace how a concept has changed in meaning over time).

Remember that you can use our template to summarise and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using!

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It’s important to keep track of your sources with references to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography, where you compile full reference information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

You can use our free APA Reference Generator for quick, correct, consistent citations.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

To begin organising your literature review’s argument and structure, you need to understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly-visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat – this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organising the body of a literature review. You should have a rough idea of your strategy before you start writing.