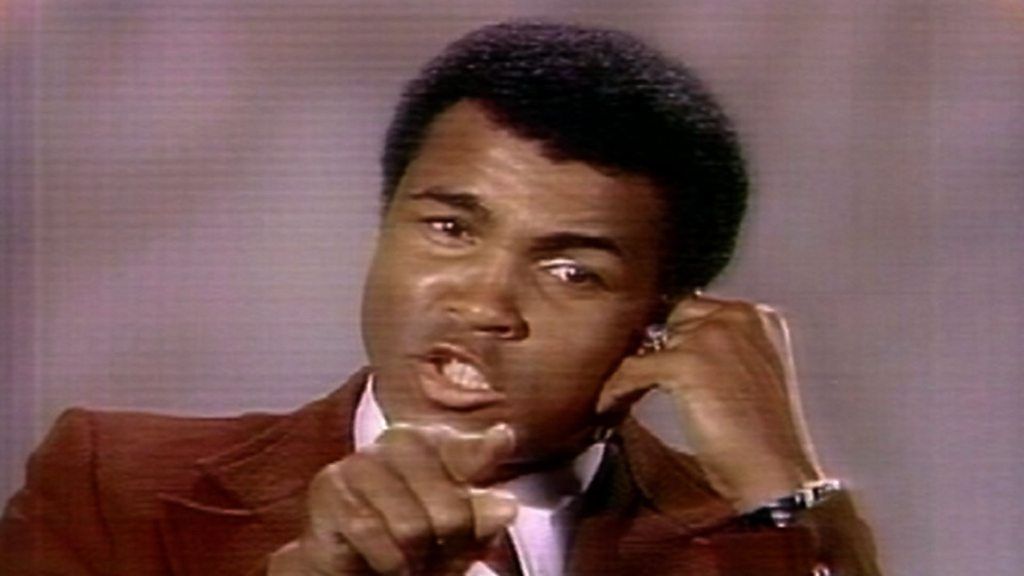

Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali was a three-time heavyweight boxing champion with an impressive 56-win record. He was also known for his public stance against the Vietnam War.

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back.

Quick Facts

Olympic gold, relationship with malcolm x and conversion to islam, vietnam war protest and supreme court case, muhammad ali’s boxing record, wives, children, and family boxing legacy, parkinson’s diagnosis, philanthropy, muhammad ali center, declining health and death, funeral and memorial service, movies about muhammad ali, who was muhammad ali.

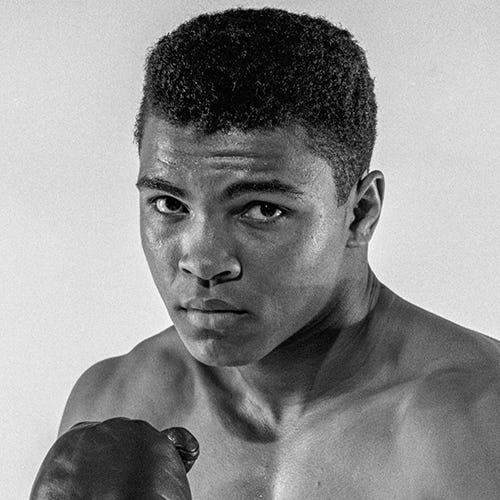

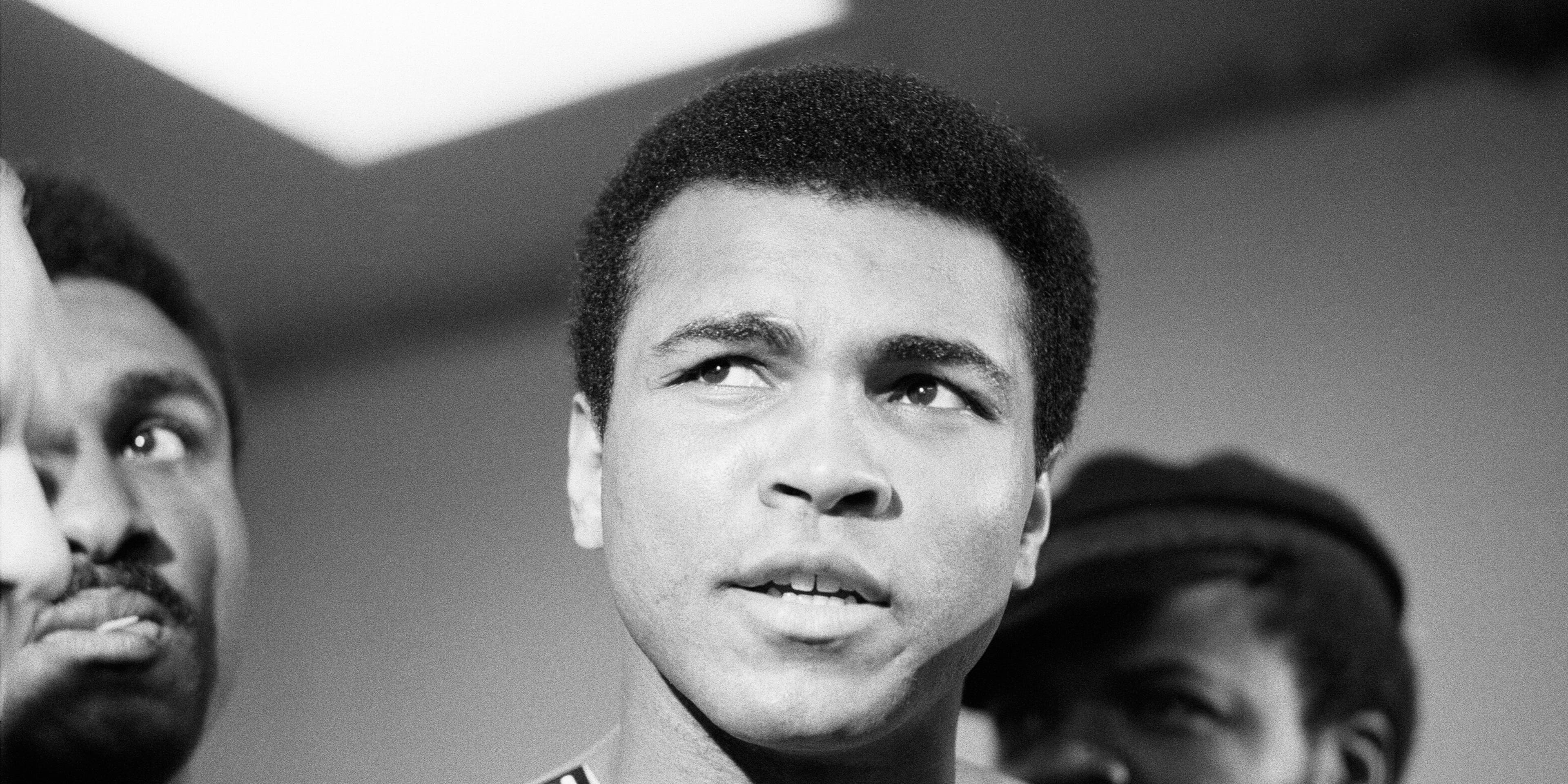

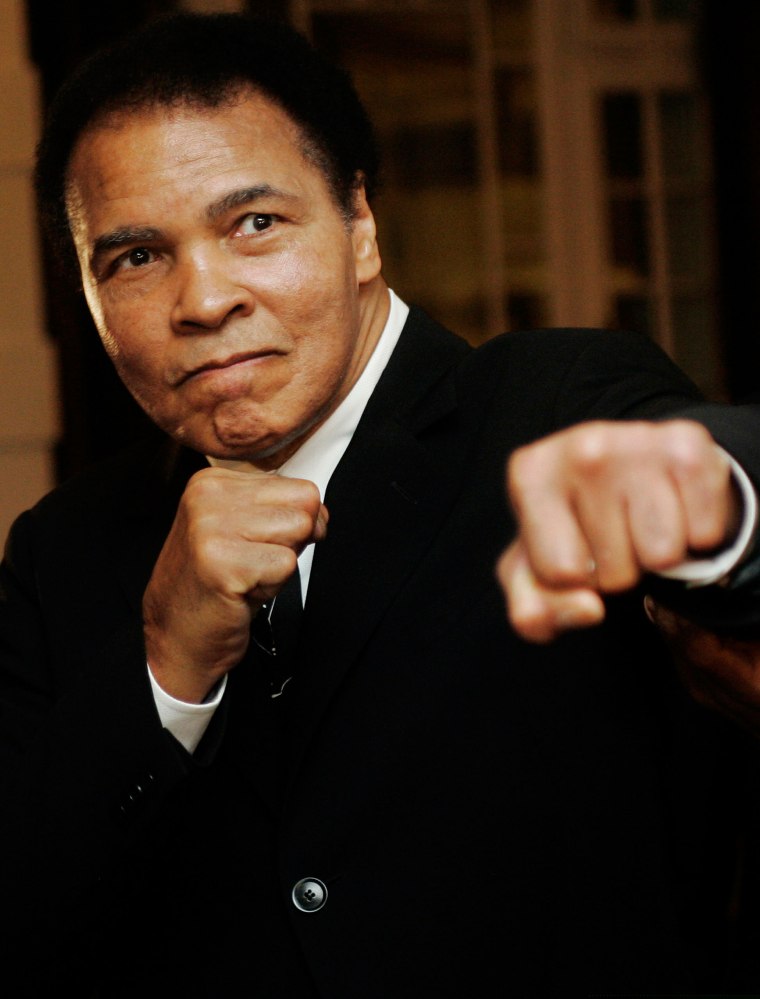

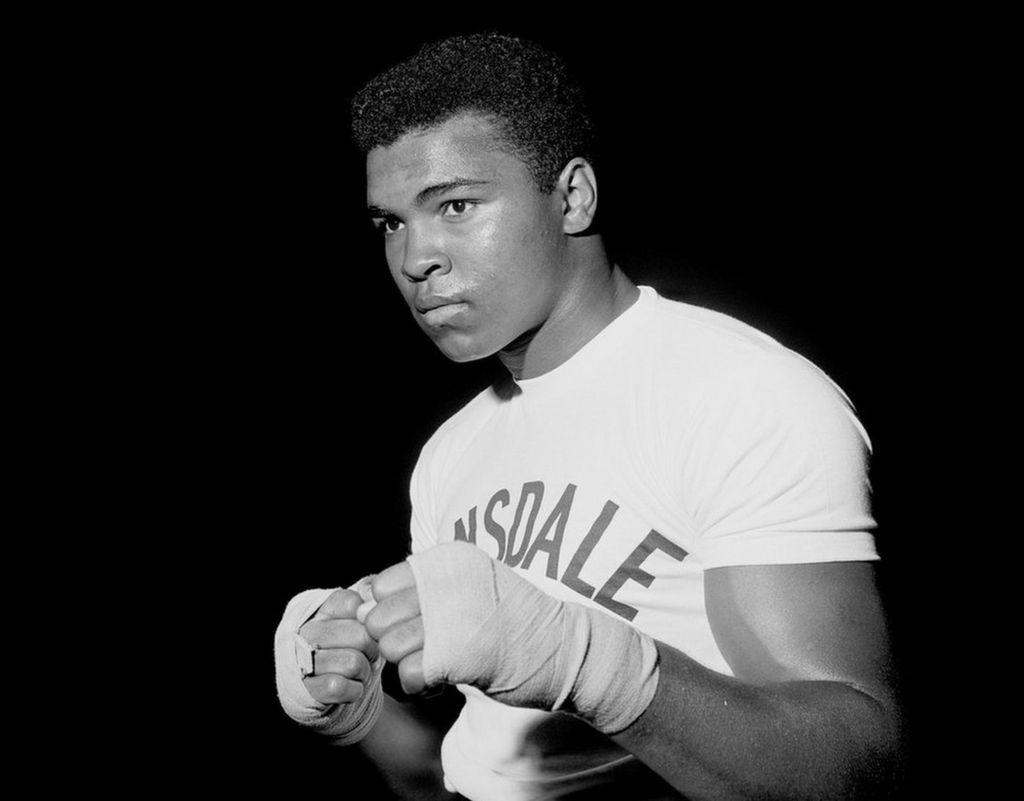

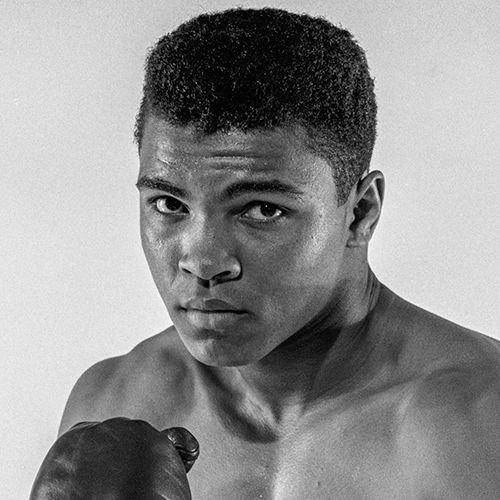

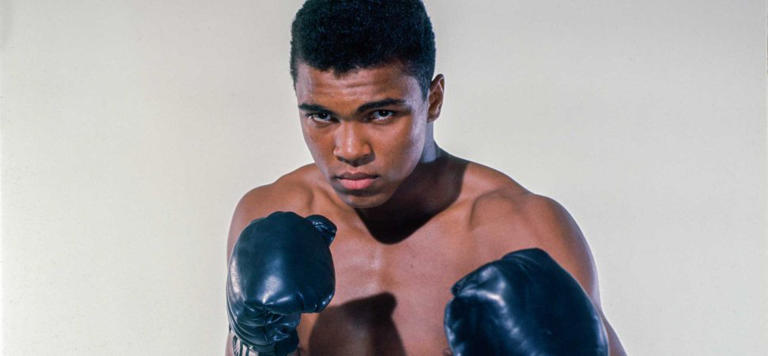

Muhammad Ali was a boxer, philanthropist, and social activist who is universally regarded as one of the greatest athletes of the 20th century. Ali became an Olympic gold medalist in 1960 and the world heavyweight boxing champion in 1964. Following his suspension for refusing military service in the Vietnam War, Ali reclaimed the heavyweight title two more times during the 1970s, winning famed bouts against Joe Frazier and George Foreman along the way. Ali retired from boxing in 1981 and devoted much of his time after to philanthropy. He earned the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2005.

FULL NAME: Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. BORN: January 17, 1942 DIED: June 3, 2016 BIRTHPLACE: Louisville, Kentucky SPOUSES: Sonji Roi (1964-1965), Belinda Boyd (1967-1977), Veronica Porché (1977-1986), and Yolanda Williams (1986-2016) CHILDREN: Maryum, Jamillah, Rasheda, Muhammad Jr., Miya, Khaliah, Hana, Laila Ali , and Asaad ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Capricorn

Muhammad Ali was born on January 17, 1942, in Louisville, Kentucky. His birth name was Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.

At an early age, young Clay showed that he wasn’t afraid of any bout—inside or outside of the ring. Growing up in the segregated South, he experienced racial prejudice and discrimination firsthand.

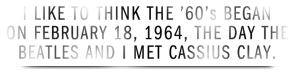

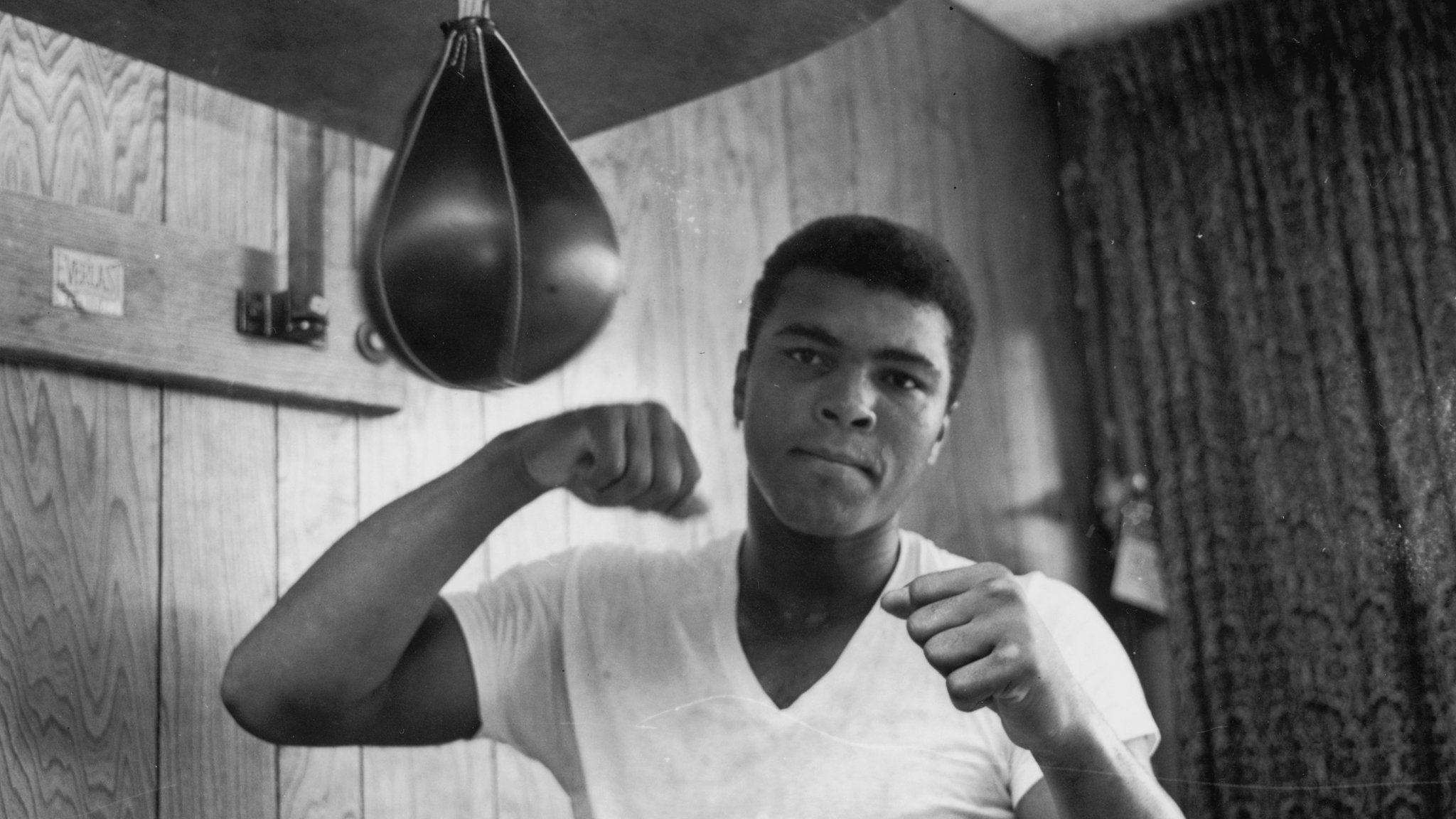

At the age of 12, Clay discovered his talent for boxing through an odd twist of fate. After his bike was stolen, Clay told police officer Joe Martin that he wanted to beat up the thief. “Well, you better learn how to fight before you start challenging people,” Martin reportedly told him at the time. In addition to being a police officer, Martin also trained young boxers at a local gym.

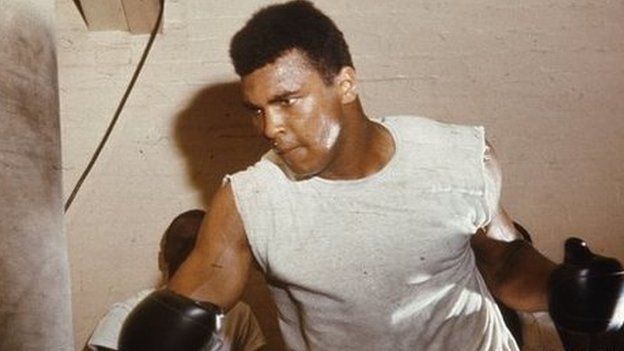

Clay started working with Martin to learn how to spar and soon began his boxing career. In his first amateur bout in 1954, he won the fight by split decision. Clay went on to win the 1956 Golden Gloves tournament for novices in the light heavyweight class. Three years later, he won the National Golden Gloves Tournament of Champions, as well as the Amateur Athletic Union’s national title for the light heavyweight division.

Clay attended mostly Black public schools, including Central High School in Louisville from 1956 to 1960. Clay often daydreamed in class and shadowboxed in the halls—he was training for the 1960 Olympics at the time—and his grades were so bad that some of his teachers wanted to hold him back from graduation. However, the school’s principal Atwood Wilson could see Clay’s potential and opposed this, sarcastically asking the staff, “Do you think I’m going to be the principal of a school that Cassius Clay didn’t finish?”

In 1960, Clay won a spot on the U.S. Olympic boxing team and traveled to Rome to compete. At 6 feet, 3 inches tall, Clay was an imposing figure in the ring, but he also became known for his lightning speed and fancy footwork. After winning his first three bouts, Clay defeated Zbigniew Pietrzkowski of Poland to win the light heavyweight Olympic gold medal.

After his Olympic victory, Clay was heralded as an American hero. He soon turned professional with the backing of the Louisville Sponsoring Group and continued overwhelming all opponents in the ring.

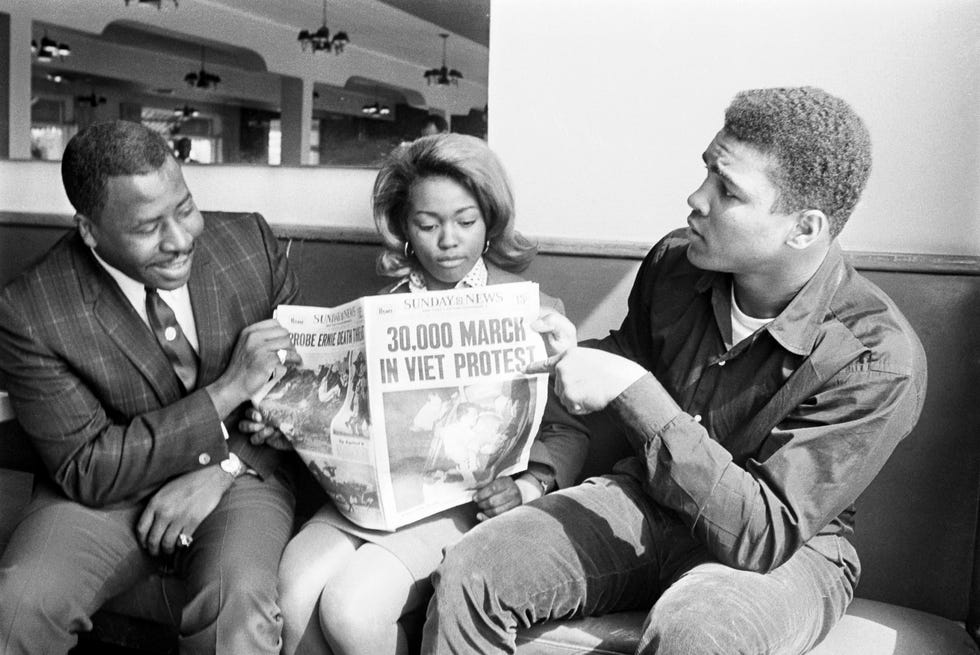

Clay met charismatic Nation of Islam minister Malcolm X at a rally in Detroit in June 1962. Floored by Malcolm X’s fearlessness as an orator, the two developed a friendship and Clay became more involved in the Black Muslim group. Malcolm X even assigned an associate to help manage Clay’s day-to-day affairs.

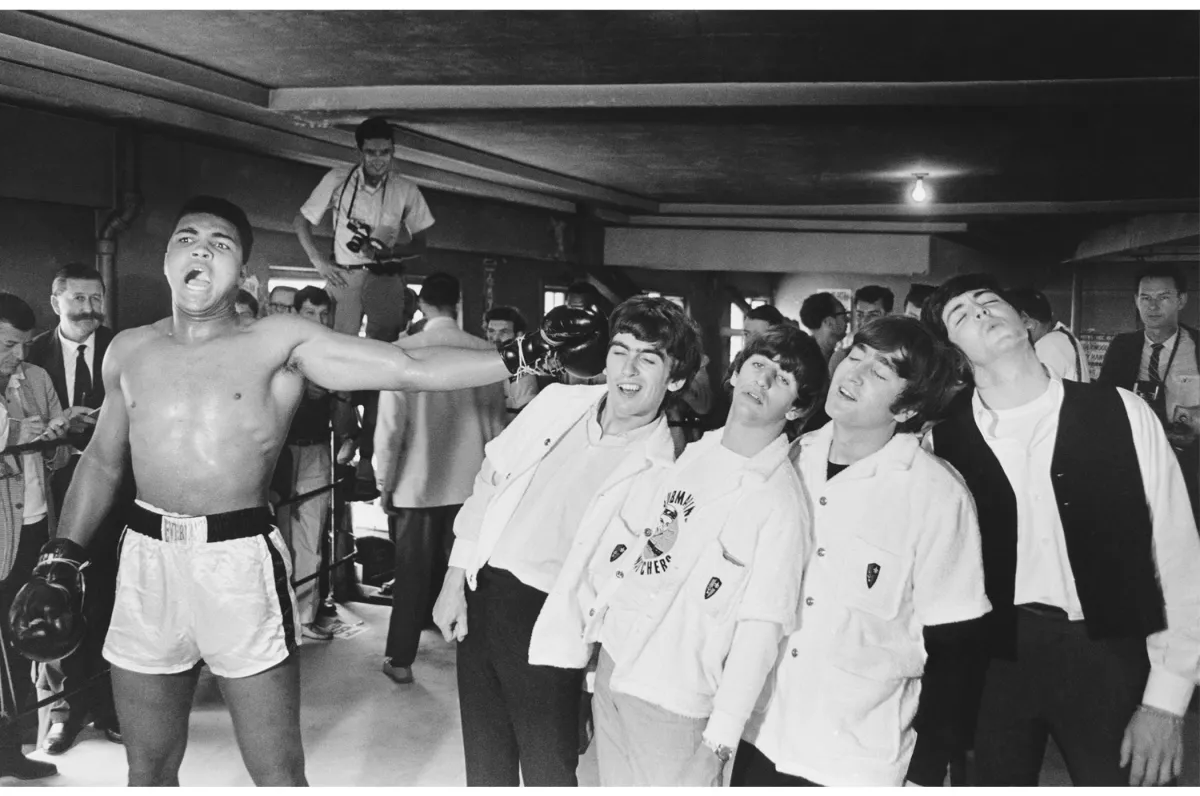

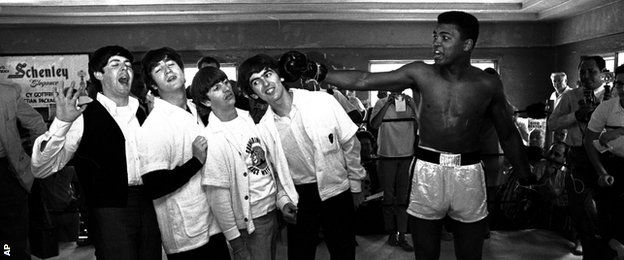

In 1964, Malcolm X brought his family to visit Clay while he trained in Florida for his February 25 title fight against Sonny Liston . Clay’s victory over Liston earned him his first world heavyweight boxing championship. Following the win, the two held an evening of reflection in a hotel room with Jim Brown and Sam Cooke that became the inspiration for the One Night in Miami stage play and 2020 drama film.

The next morning, on February 26, Clay announced his affiliation with the Nation of Islam. At first, he called himself Cassius X before settling on the name Muhammad Ali. Surprisingly, his allegiances were with supreme leader Elijah Muhammad and not the exiled Malcolm X. Ali and Malcolm’s friendship quickly fractured, and the two went their separate ways by that spring.

Ali showed little remorse upon Malcolm X’s murder on February 21, 1965, but admitted in his 2005 memoir Soul of a Butterfly : “Turning my back on Malcolm was one of the mistakes that I regret most in my life.”

The boxer eventually converted to orthodox Islam during the 1970s.

Ali started a different kind of fight with his outspoken views against the Vietnam War. Drafted into the military in April 1967, he refused to serve on the grounds that he was a practicing Muslim minister with religious beliefs that prevented him from fighting. He was arrested for committing a felony and almost immediately stripped of his world title and boxing license.

The U.S. Justice Department pursued a legal case against Ali and denied his claim for conscientious objector status. He was found guilty of violating Selective Service laws and sentenced to five years in prison in June 1967 but remained free while appealing his conviction.

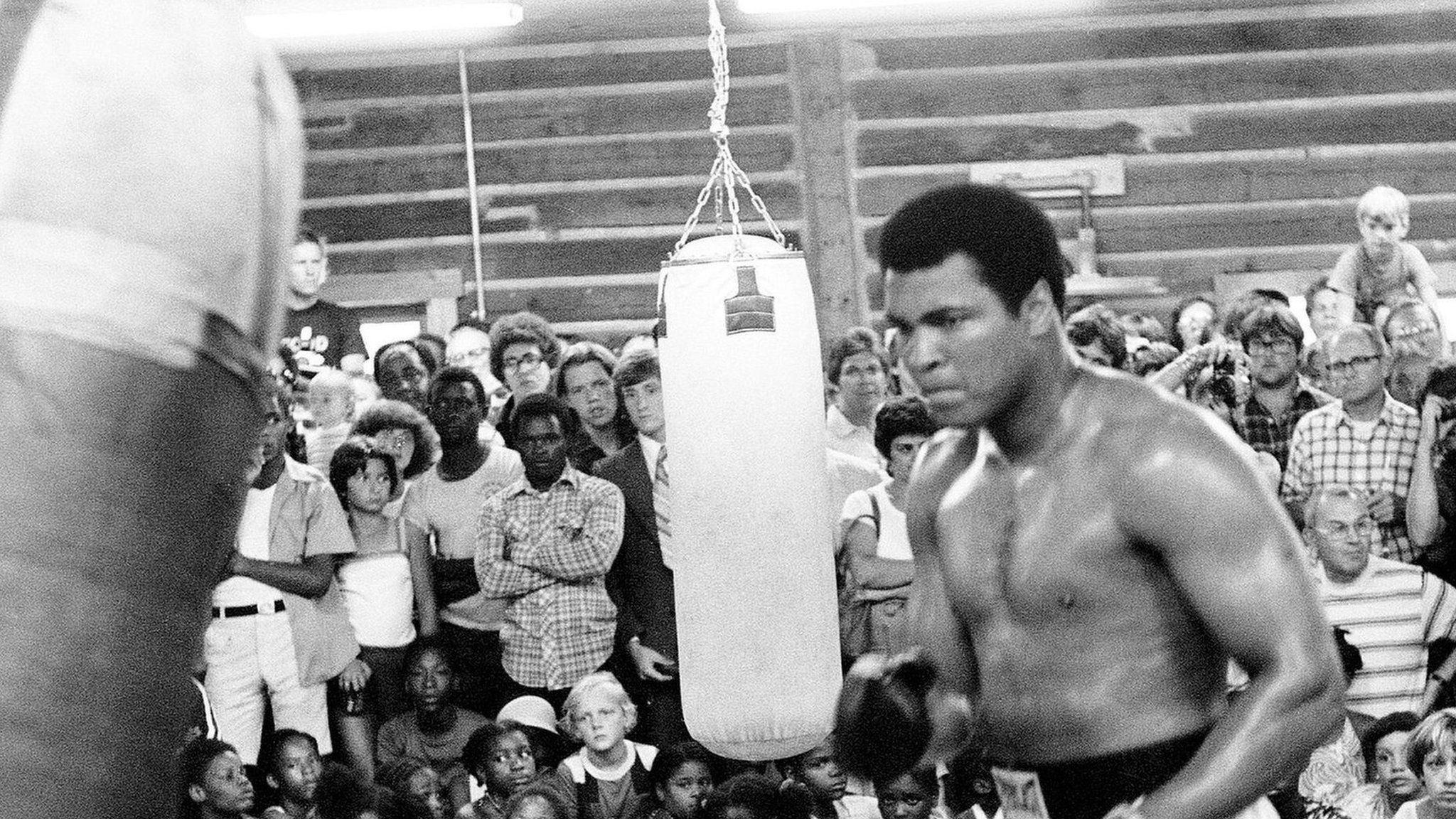

Unable to compete professionally in the meantime, Ali missed more than three prime years of his athletic career. Following his suspension, Ali found refuge on Chicago’s South Side, where he lived from the mid-1960s through the late 1970s. He continued training, formed amateur boxing leagues, and fought whomever he could in local gyms.

Finally granted a license to fight in 1970 in Georgia, which did not have a statewide athletic commission, Ali returned to the ring at Atlanta’s City Auditorium on October 26 with a win over Jerry Quarry. A few months later, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned his conviction in June 1971, allowing Ali to fight on a regular basis.

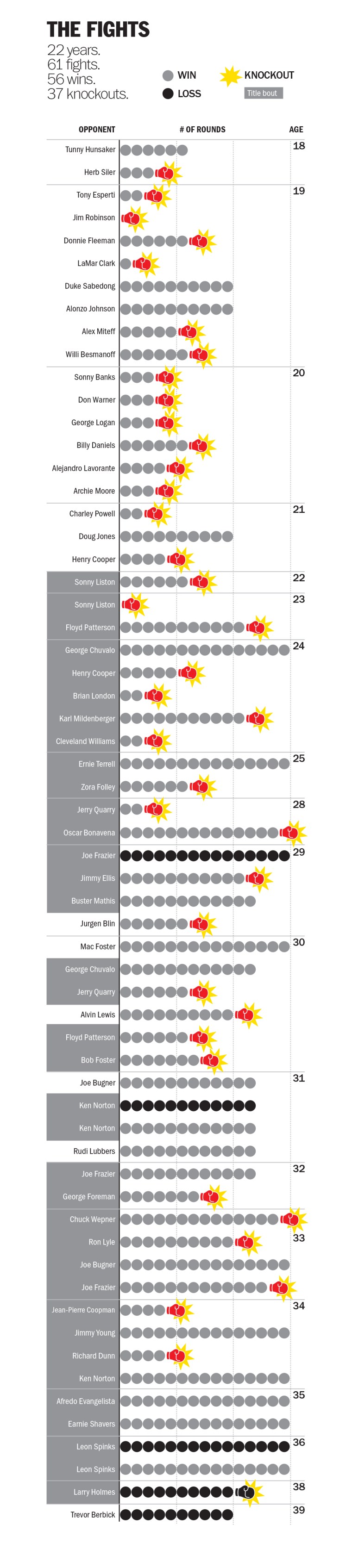

Ali had a career record of 56 wins, five losses, and 37 knockouts before his retirement in 1981 at the age of 39.

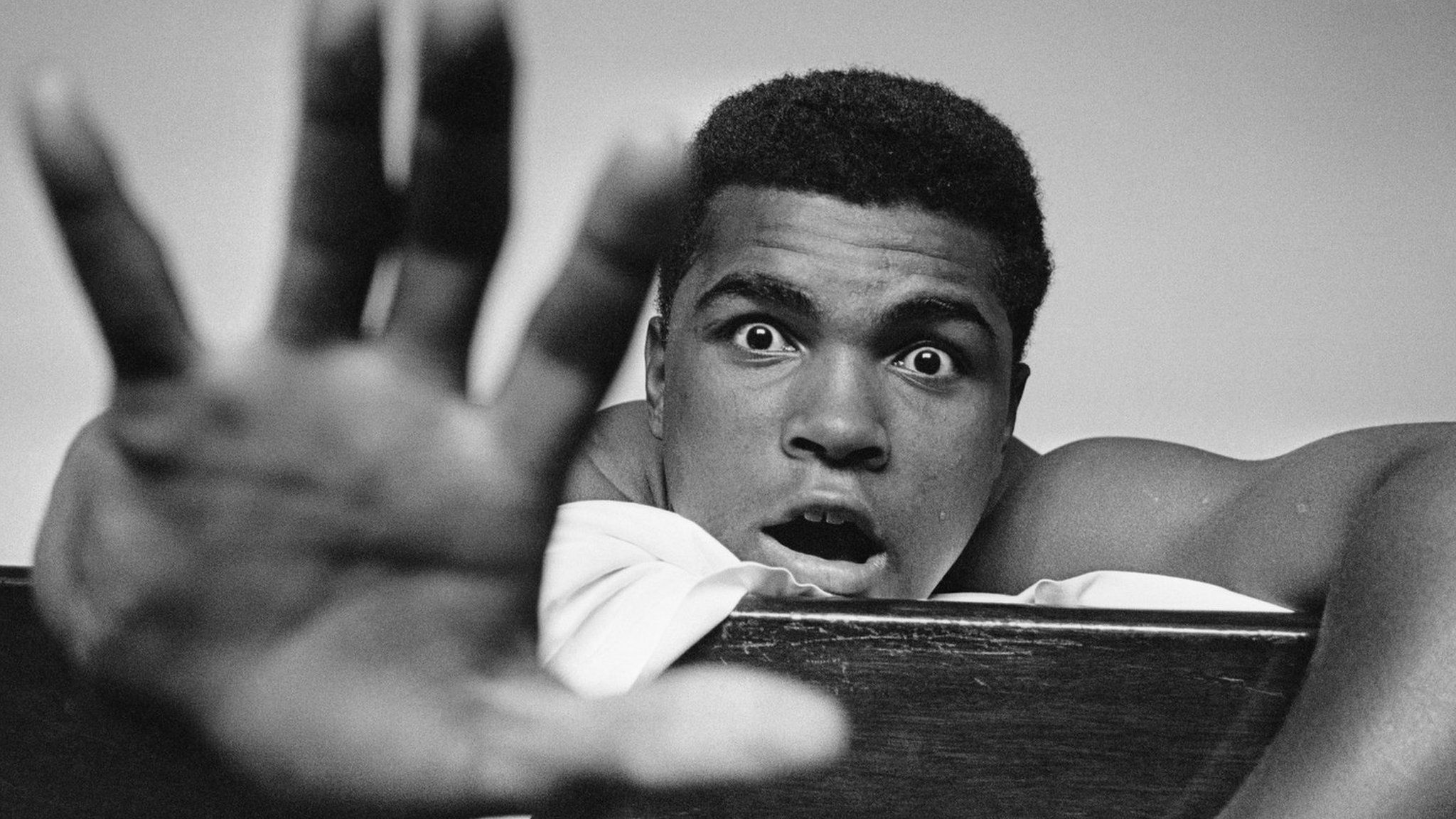

Often referring to himself as “The Greatest,” Ali was not afraid to sing his own praises. He was known for boasting about his skills before a fight and for his colorful descriptions and phrases. In one of his more famously quoted descriptions, Ali told reporters that he could “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” in the boxing ring.

A few of his more well-known bouts include the following:

Sonny Liston

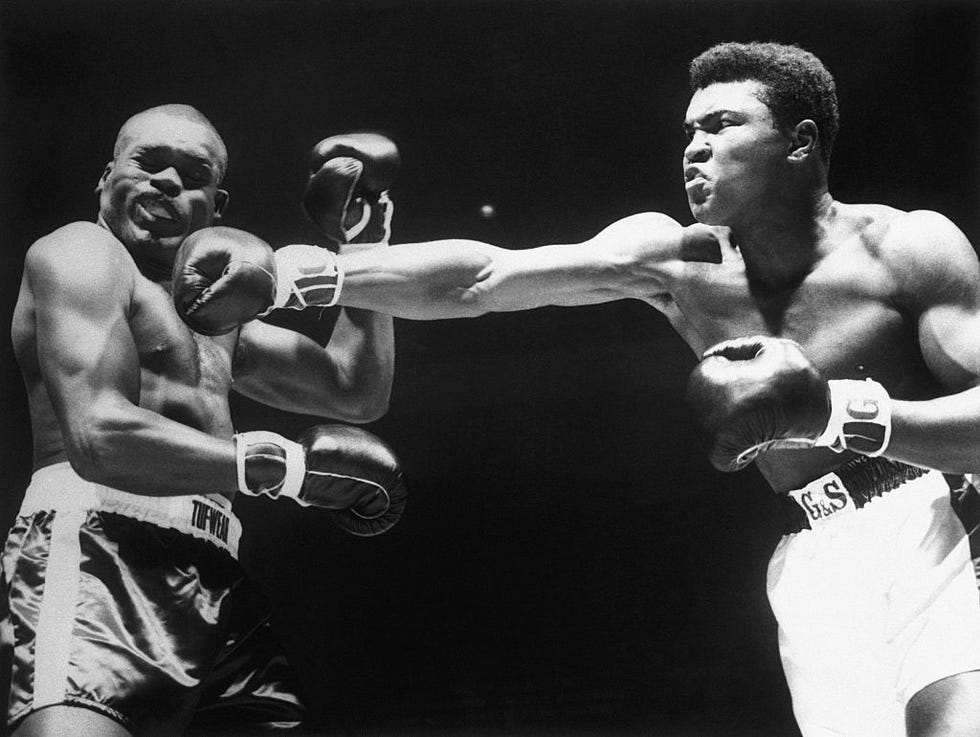

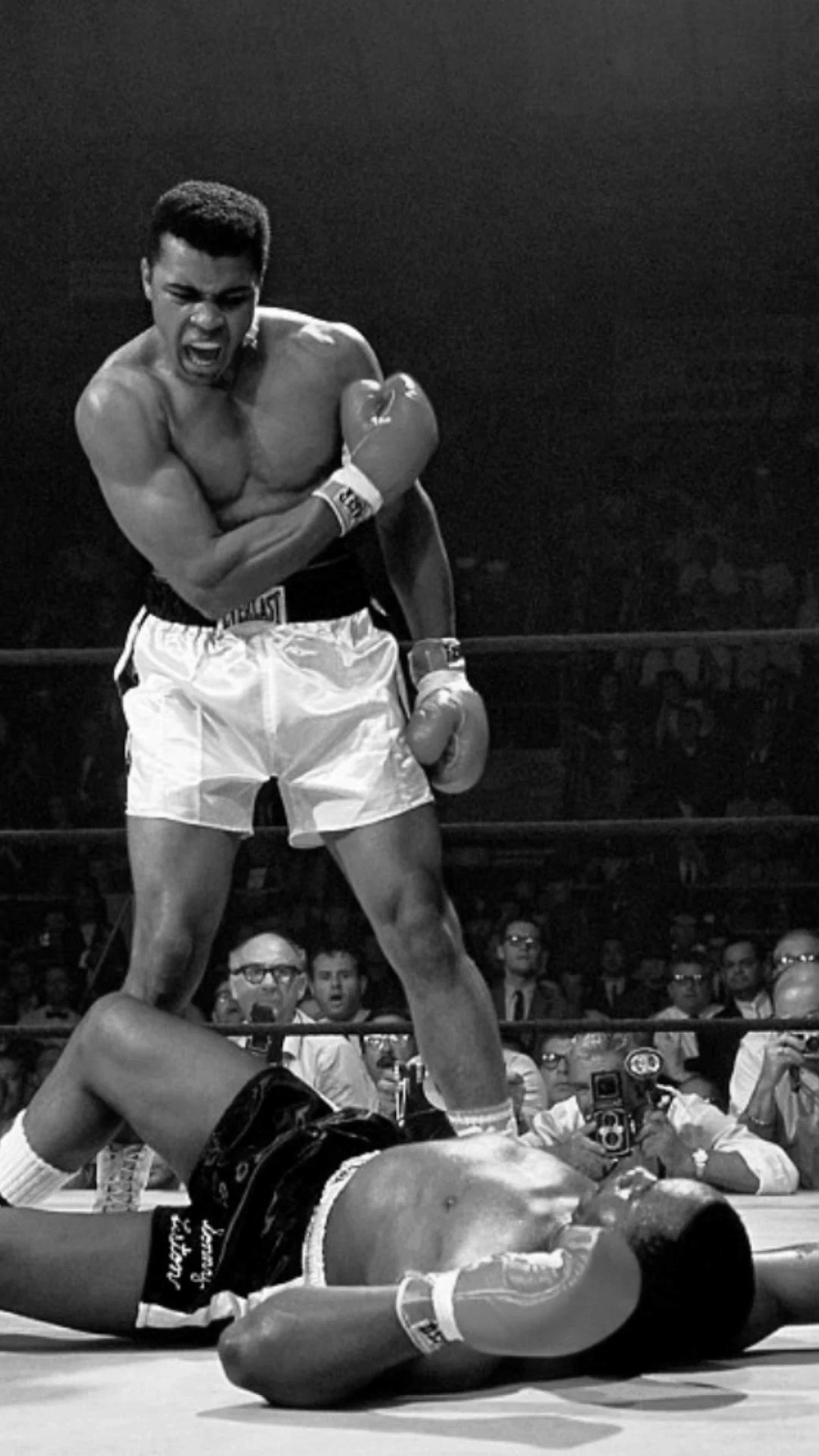

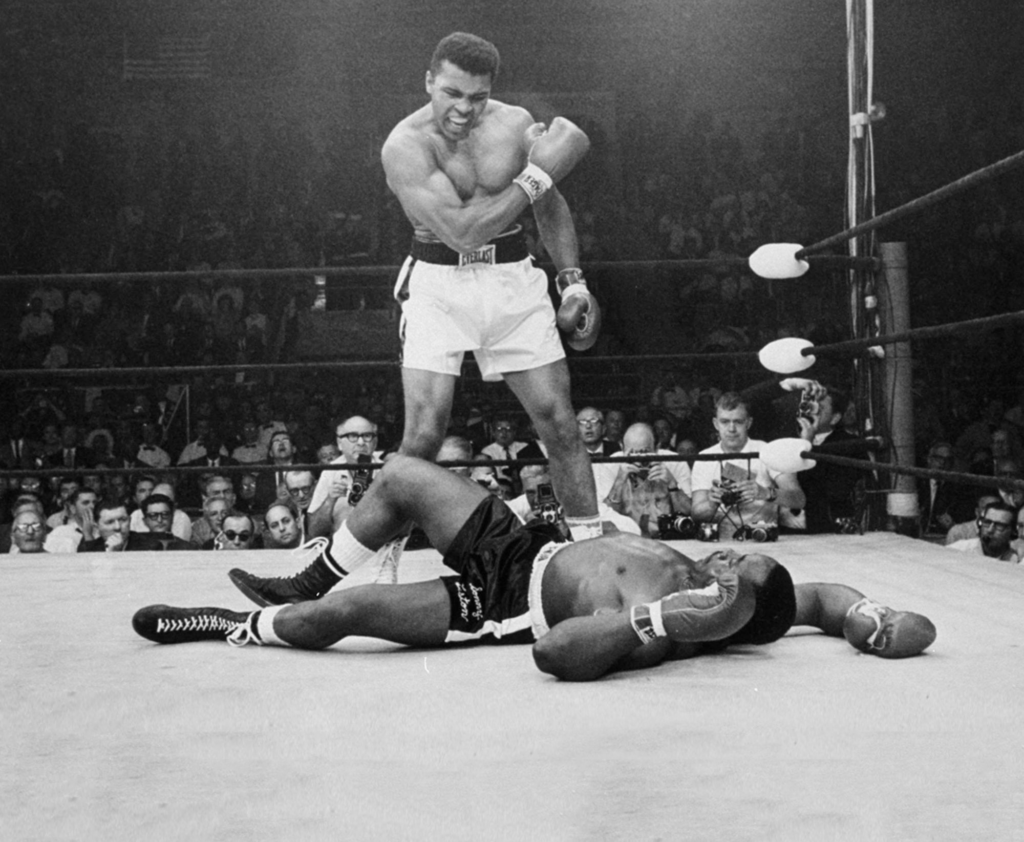

After winning gold at the 1960 Olympics, Ali took out British heavyweight champion Henry Cooper in 1963. He then knocked out Sonny Liston on February 25, 1964, to become the heavyweight champion of the world.

Joe Frazier

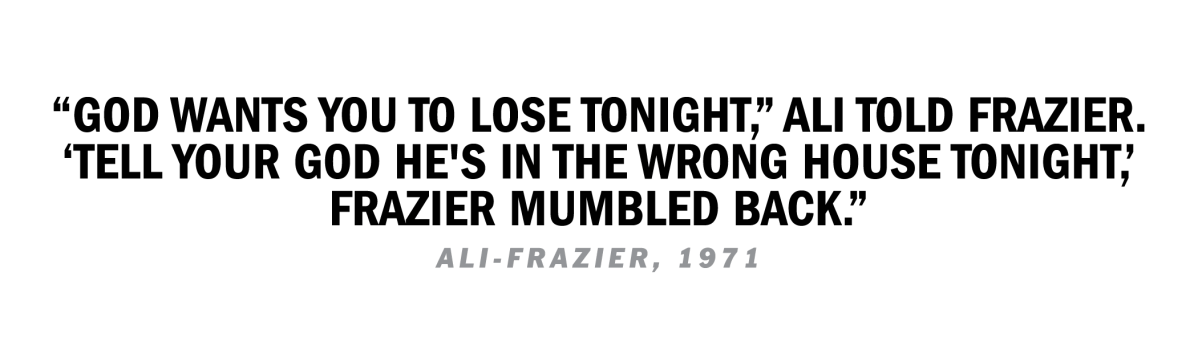

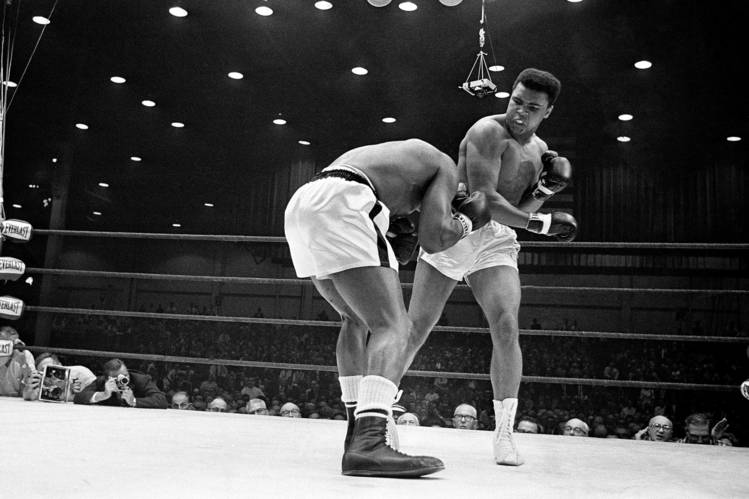

On March 8, 1971, Ali took on Joe Frazier in what has been called the “Fight of the Century.” Frazier and Ali went toe-to-toe for 14 rounds before Frazier dropped Ali with a vicious left hook in the 15th. Ali recovered quickly, but the judges awarded the decision to Frazier, handing Ali his first professional loss after 31 wins.

After suffering a loss to Ken Norton, Ali beat Frazier in a rematch on January 28, 1974.

In 1975, Ali and Frazier locked horns again for their grudge match on October 1 in Quezon City, Philippines. Dubbed the “Thrilla in Manila,” the bout nearly went the distance, with both men delivering and absorbing tremendous punishment. However, Frazier’s trainer threw in the towel after the 14th round, giving the hard-fought victory to Ali.

George Foreman

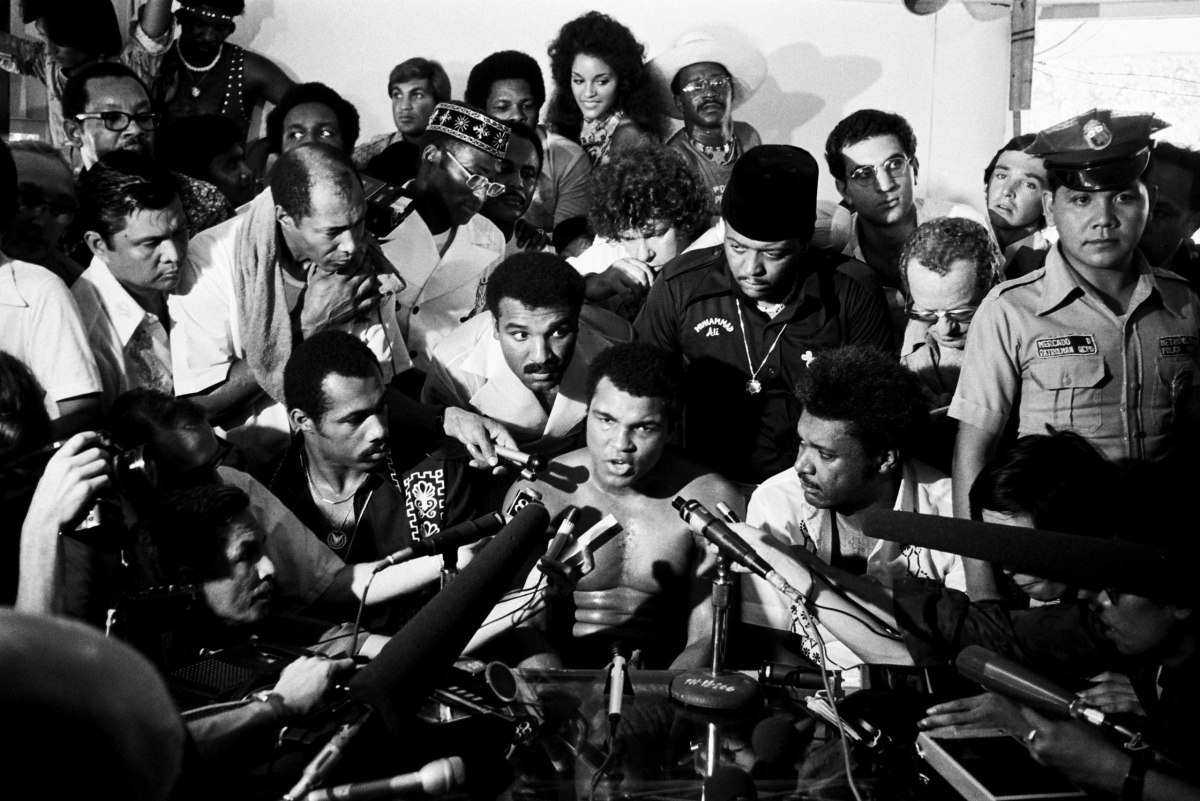

Another legendary Ali fight took place on October 30, 1974, against undefeated heavyweight champion George Foreman . Billed as the “Rumble in the Jungle,” the bout was organized by promoter Don King and held in Kinshasa, Zaire.

For once, Ali was seen as the underdog to the younger, massive Foreman, but he silenced his critics with a masterful performance. He baited Foreman into throwing wild punches with his “rope-a-dope” technique, before stunning his opponent with an eighth-round knockout to reclaim the heavyweight title.

Leon Spinks

After losing his title to Leon Spinks on February 15, 1978, Ali defeated him months later in a rematch on September 15. Ali became the first boxer to win the heavyweight championship three times.

Larry Holmes

Following a brief retirement, Ali returned to the ring to face Larry Holmes on October 2, 1980, but was overmatched against the younger champion.

Following one final loss in 1981, to Trevor Berbick, the boxing great retired from the sport at age 39.

Ali was married four times and had nine children, including two children—daughters Miya and Khaliah—he fathered outside of marriage.

Ali married his first wife, Sonji Roi, in 1964. They divorced a little more than one year later when she refused to adopt the Nation of Islam dress and customs.

Ali married his second wife, 17-year-old Belinda Boyd, in 1967. Boyd and Ali had four children together: Maryum, born in 1969; Jamillah and Rasheda, both born in 1970; and Muhammad Ali Jr., born in 1972. Boyd and Ali’s divorce was finalized in 1977.

At the same time Ali was married to Boyd, he traveled openly with Veronica Porché, who became his third wife in 1977. The pair had two daughters together, Hana and Laila Ali . The latter followed in Ali’s footsteps by becoming a champion boxer. Porché and Ali divorced in 1986.

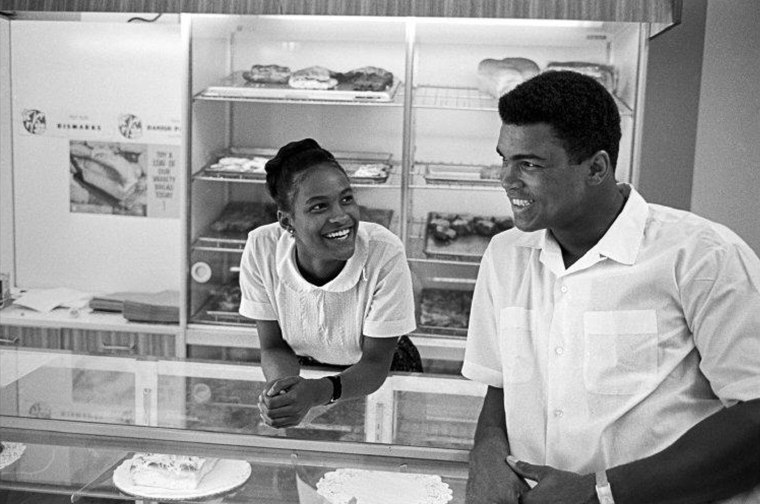

Ali married his fourth and final wife Yolanda, who went by Lonnie, in 1986. The pair had known each other since Lonnie was just 6 and Ali was 21; their mothers were best friends and raised their families on the same street. Ali and Lonnie had one son together, Asaad, and remained married until Ali’s death.

Grandchildren

Rasheda’s son Nico Walsh Ali became a boxer like his grandfather and aunt. In 2021, he signed a deal with legendary Top Rank promoter Bob Arum, who promoted 27 of Muhammad Ali’s bouts. He won his first eight professional fights, according to database BoxRec.

Nico’s brother, Biaggio Ali Walsh, was a star football running back, helping lead national powerhouse Bishop Gorman High School in Las Vegas to the top of the USA Today rankings from 2014 through 2016. He played collegiately at the University of California, Berkeley and the University of Nevada, Las Vegas before becoming an amateur mixed martial artist.

The brothers have drawn the attention of social media celebrity Jake Paul, a novice boxer who has said he’d like to fight both and “erase” them.

One of Ali’s other grandsons, Jacob Ali-Wertheimer, competed in NCAA track and field at Harvard University and graduated in 2021.

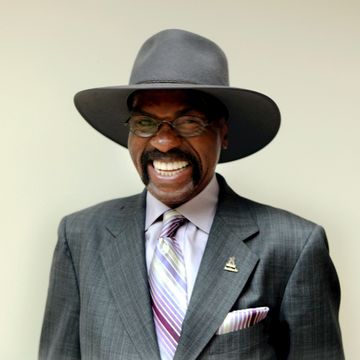

In 1984, Ali announced that he had Parkinson’s disease, a degenerative neurological condition. Despite the progression of Parkinson’s and the onset of spinal stenosis, he remained active in public life.

Ali raised funds for the Muhammad Ali Parkinson Center in Phoenix, Arizona. And he was on hand to celebrate the inauguration of the first Black president in January 2009, when Barack Obama was sworn into office.

In his retirement, Ali devoted much of his time to philanthropy. Over the years, Ali supported the Special Olympics and the Make-A-Wish Foundation, among other organizations. In 1996, he lit the Olympic cauldron at the Summer Olympic Games in Atlanta, an emotional moment in sports history.

Ali traveled to numerous countries, including Mexico and Morocco, to help out those in need. In 1998, he was chosen to be a United Nations Messenger of Peace because of his work in developing nations.

In 2005, Ali received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President George W. Bush .

Ali also received the President’s Award from the NAACP in 2009 for his public service efforts. Other recipients of the award have included include Ella Fitzgerald , Venus and Serena Williams , Kerry Washington , Spike Lee , John Legend , Rihanna , and LeBron James .

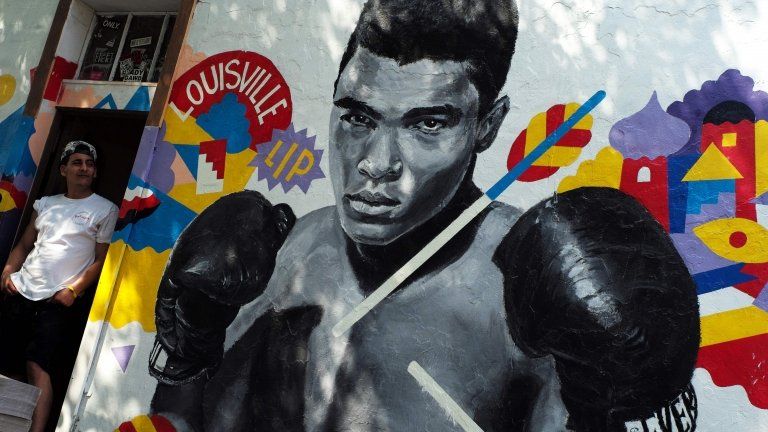

Ali opened the Muhammad Ali Center , a multicultural center with a museum dedicated to his life and legacy, in his hometown of Louisville in 2005.

“I am an ordinary man who worked hard to develop the talent I was given,” he said. “Many fans wanted to build a museum to acknowledge my achievements. I wanted more than a building to house my memorabilia. I wanted a place that would inspire people to be the best that they could be at whatever they chose to do, and to encourage them to be respectful of one another.”

Ali lived the final decade of his live in the Phoenix suburb of Paradise Valley, Arizona.

A few years before his death, Ali underwent surgery for spinal stenosis, a condition causing the narrowing of the spine, which limited his mobility and ability to communicate. In early 2015, he battled pneumonia and was hospitalized for a severe urinary tract infection.

Ali died on June 3, 2016, in Scottsdale, Arizona, after being hospitalized for what was reportedly a respiratory issue. He was 74 years old.

Years before his passing, Ali had planned his own memorial services, saying he wanted to be “inclusive of everyone, where we give as many people an opportunity that want to pay their respects to me,” according to a family spokesman.

The three-day event, which took place in Ali’s hometown of Louisville, included an “I Am Ali” public arts festival, entertainment and educational offerings sponsored by the city, an Islamic prayer program, and a memorial service.

Prior to the memorial service, a funeral procession traveled 20 miles through Louisville, past Ali’s childhood home, his high school, the first boxing gym where he trained, and along Ali Boulevard as tens of thousands of fans tossed flowers on his hearse and cheered his name.

The champ’s memorial service was held at the KFC Yum Center arena with close to 20,000 people in attendance. Speakers included religious leaders from various faiths: Attallah Shabazz, Malcolm X’s eldest daughter; broadcaster Bryant Gumbel; former President Bill Clinton ; comedian Billy Crystal; Ali’s daughters Maryum and Rasheda; and his widow, Lonnie.

“Muhammad indicated that when the end came for him, he wanted us to use his life and his death as a teaching moment for young people, for his country, and for the world,” Lonnie said. “In effect, he wanted us to remind people who are suffering that he had seen the face of injustice—that he grew up during segregation and that during his early life he was not free to be who he wanted to be. But he never became embittered enough to quit or to engage in violence.”

Clinton spoke about how Ali found self-empowerment: “I think he decided, before he could possibly have worked it all out, and before fate and time could work their will on him, he decided he would not ever be disempowered. He decided that not his race, nor his place, the expectations of others—positive, negative, or otherwise—would strip from him the power to write his own story.”

Crystal, who was a struggling comedian when he became friends with Ali, said of the boxing legend: “Ultimately, he became a silent messenger for peace, who taught us that life is best when you build bridges between people, not walls.”

Pallbearers included Will Smith , who once portrayed Ali on film, and former heavyweight champions Mike Tyson and Lennox Lewis. Ali is buried at the Cave Hill National Cemetery in Louisville.

Ali’s stature as a legend continues to grow even after his death. He is celebrated not only for his remarkable athletic skills but for his willingness to speak his mind and his courage to challenge the status quo.

Ali played himself in the 1977 film The Greatest , which explored parts of his life such as his rise to boxing fame, conversion to Islam, and refusal to serve in Vietnam.

The 1996 documentary When We Were Kings explores Ali’s training process for his 1974 fight against George Foreman and the African political climate at the time. Directed by Leon Gast, the film won an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

Actor Will Smith played Ali in the biopic film Ali, released in 2001. For the performance, Smith received an Academy Award nomination for Best Actor.

Ali’s relationship with Malcolm X is explored in the fictionalized 2020 drama One Night in Miami and the 2021 documentary Blood Brothers: Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali .

- The man who views the world at 50 the same as he did at 20 has wasted 30 years of his life.

- It isn’t the mountains ahead to climb that wear you out; it’s the pebble in your shoe.

- I’m gonna float like a butterfly, sting like a bee. The hands can’t hit what the eyes can’t see.

- I am an ordinary man who worked hard to develop the talent I was given.

- I’m the champion of the world. I’m the greatest thing that ever lived. I’m so great I don’t have a mark on my face. I shook up the world! I shook up the world!

- If Clay says a mosquito can pull a plow, don’t ask how—Hitch him up!

- You get the impression while watching him fight that he plays cat and mouse, then turns out the light.

- The real enemy of my people is here. I will not disgrace my religion, my people, or myself by becoming a tool to enslave those who are fighting for their own justice, freedom, and equality.

- Religions all have different names, but they all contain the same truths. I think the people of our religion should be tolerant and understand people believe different things.

- It’s just a job. Grass grows, birds fly, waves pound the sand. I beat people up.

- I set out on a journey of love, seeking truth, peace, and understanding. l am still learning.

- Truly great people in history never wanted to be great for themselves.

- At night when I go to bed, I ask myself, “If I don’t wake up tomorrow, would I be proud of how I lived today?”

- This is the story about a man with iron fists and a beautiful tan.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Tyler Piccotti first joined the Biography.com staff as an Associate News Editor in February 2023, and before that worked almost eight years as a newspaper reporter and copy editor. He is a graduate of Syracuse University. When he's not writing and researching his next story, you can find him at the nearest amusement park, catching the latest movie, or cheering on his favorite sports teams.

Famous Athletes

The Final Four Is Personal for Caitlin Clark

Sha’Carri Richardson

Aaron Rodgers

Florence Joyner

Lionel Messi

10 Things You Might Not Know About Travis Kelce

Every Black Quarterback to Play in the Super Bowl

Patrick Mahomes

What Is Soccer Star Cristiano Ronaldo’s Net Worth?

Jackie Joyner-Kersee

Rubin Carter

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Muhammad Ali

By: History.com Editors

Updated: February 27, 2024 | Original: December 16, 2009

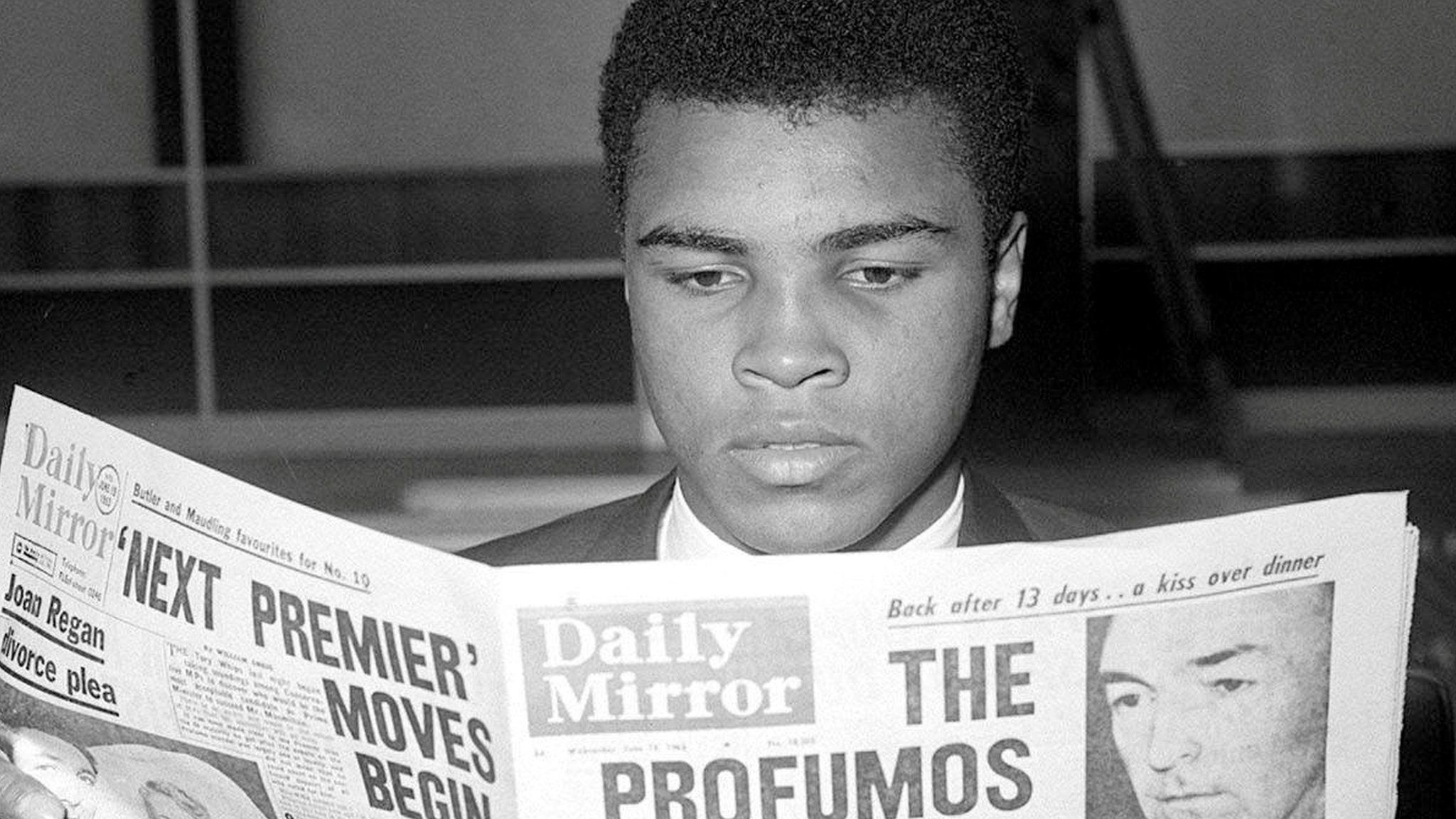

Muhammad Ali (1942-2016) was an American former heavyweight champion boxer and one of the greatest sporting figures of the 20th century. An Olympic gold medalist and the first fighter to capture the heavyweight title three times, Ali won 56 times in his 21-year professional career. Ali’s outspokenness on issues of race, religion and politics made him a controversial figure during his career, and the heavyweight’s quips and taunts were as quick as his fists.

Born Cassius Clay Jr., Ali changed his name in 1964 after joining the Nation of Islam. Citing his religious beliefs, he refused military induction and was stripped of his heavyweight championship and banned from boxing for three years during the prime of his career. Parkinson’s syndrome severely impaired Ali’s motor skills and speech, but he remained active as a humanitarian and goodwill ambassador.

Muhammad Ali’s Early Years and Amateur Career

Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr., the elder son of Cassius Marcellus Clay Sr. (1912-1990) and Odessa Grady Clay (1917-1994), was born on January 17, 1942, in Louisville, Kentucky . It was a red-and-white Schwinn that steered the future heavyweight champion to the sport of boxing. When his beloved bicycle was stolen, a tearful 12-year-old Clay reported the theft to Louisville police officer Joe Martin (1916-1996) and vowed to pummel the culprit. Martin, who was also a boxing trainer, suggested that the upset youngster first learn how to fight, and he took Clay under his wing. Six weeks later, Clay won his first bout in a split decision.

Did you know? Muhammad Ali has appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated 38 times, second only to basketball great Michael Jordan.

By age 18 Clay had captured two national Golden Gloves titles, two Amateur Athletic Union national titles and 100 victories against eight losses. After graduating high school, he traveled to Rome and won the light heavyweight gold medal in the 1960 Summer Olympics.

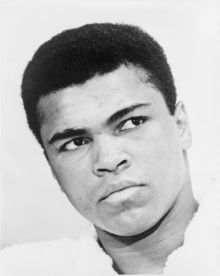

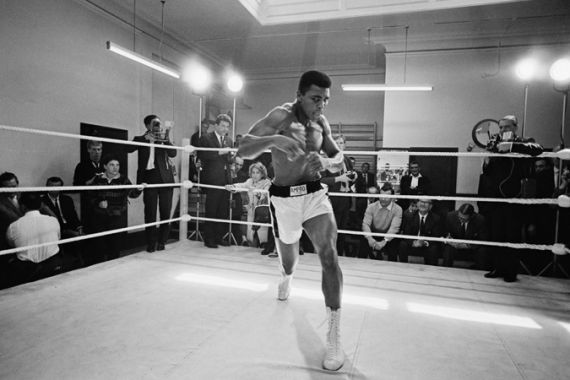

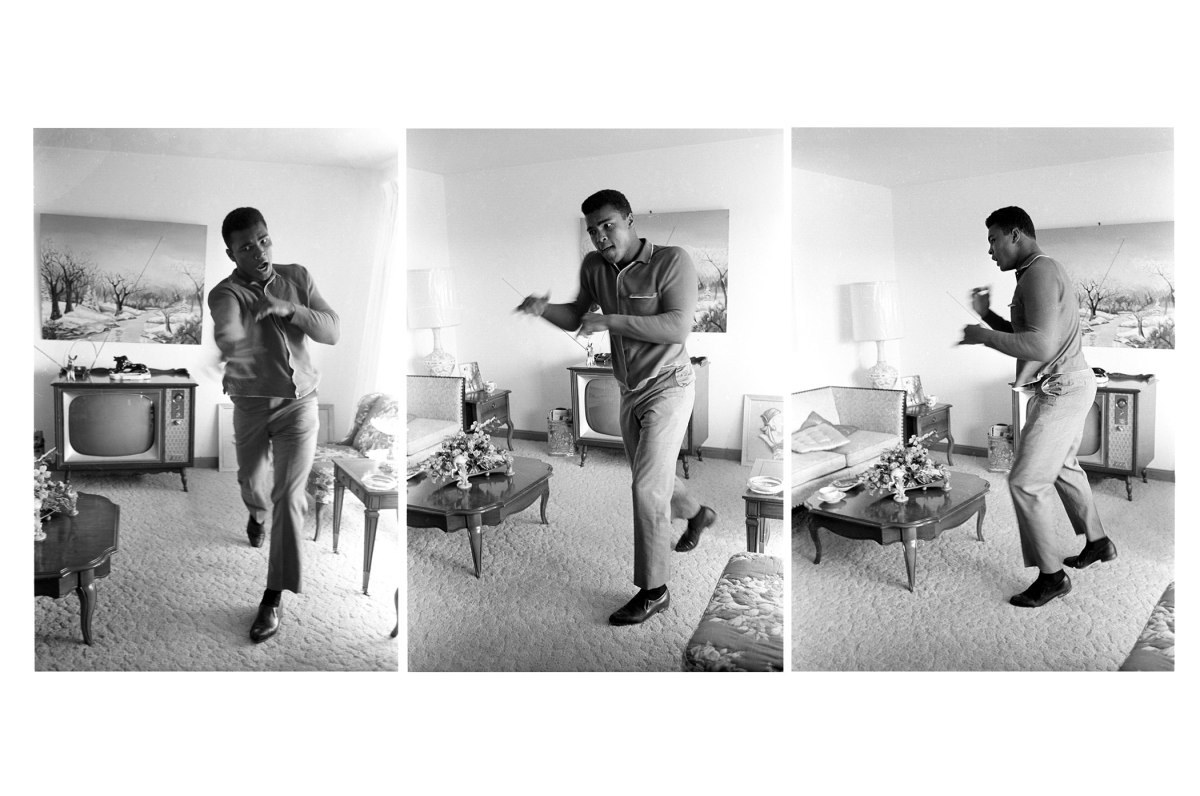

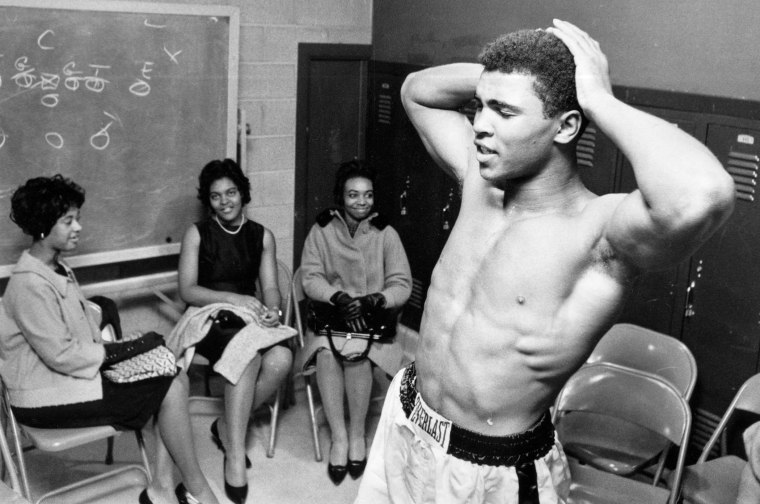

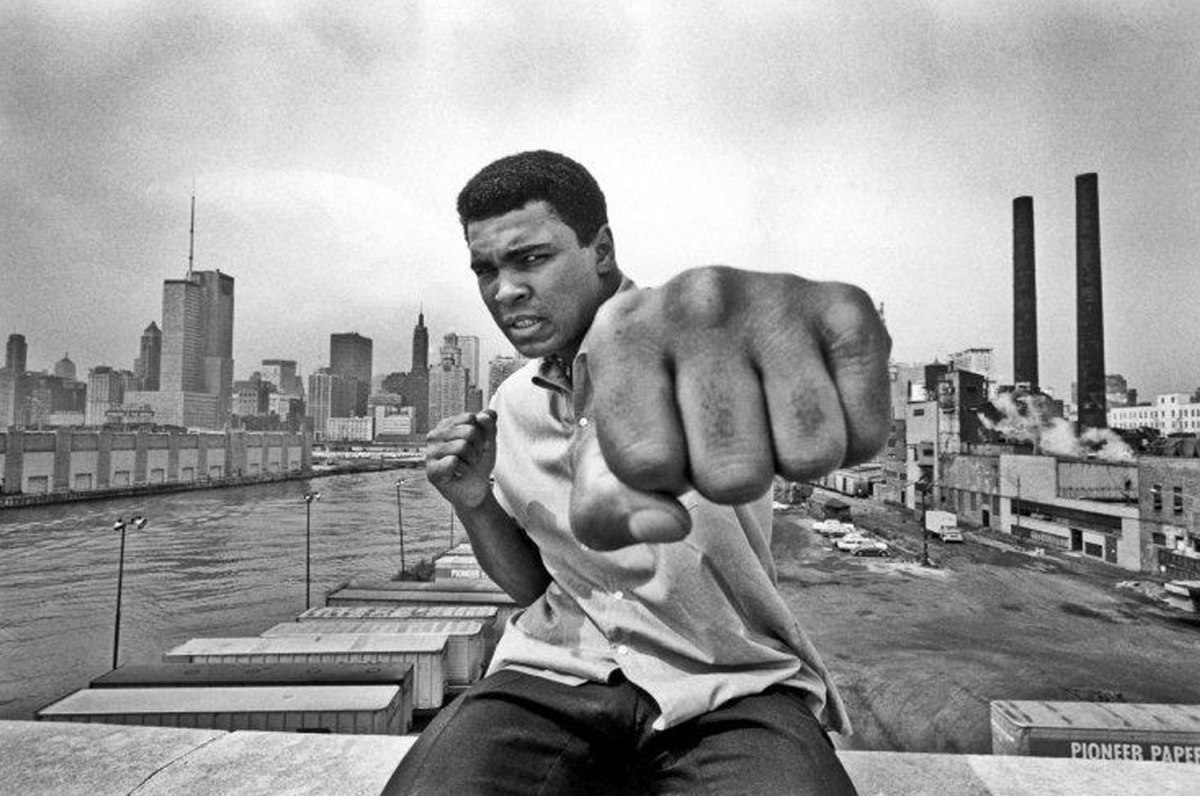

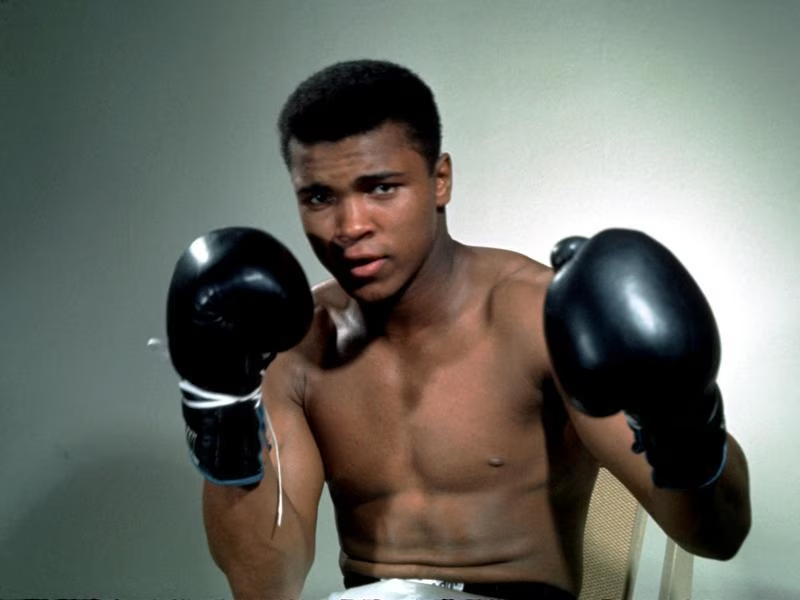

Clay won his professional boxing debut on October 29, 1960, in a six-round decision. From the start of his pro career, the 6-foot-3-inch heavyweight overwhelmed his opponents with a combination of quick, powerful jabs and foot speed, and his constant braggadocio and self-promotion earned him the nickname “Louisville Lip.”

Muhammad Ali: Heavyweight Champion of the World

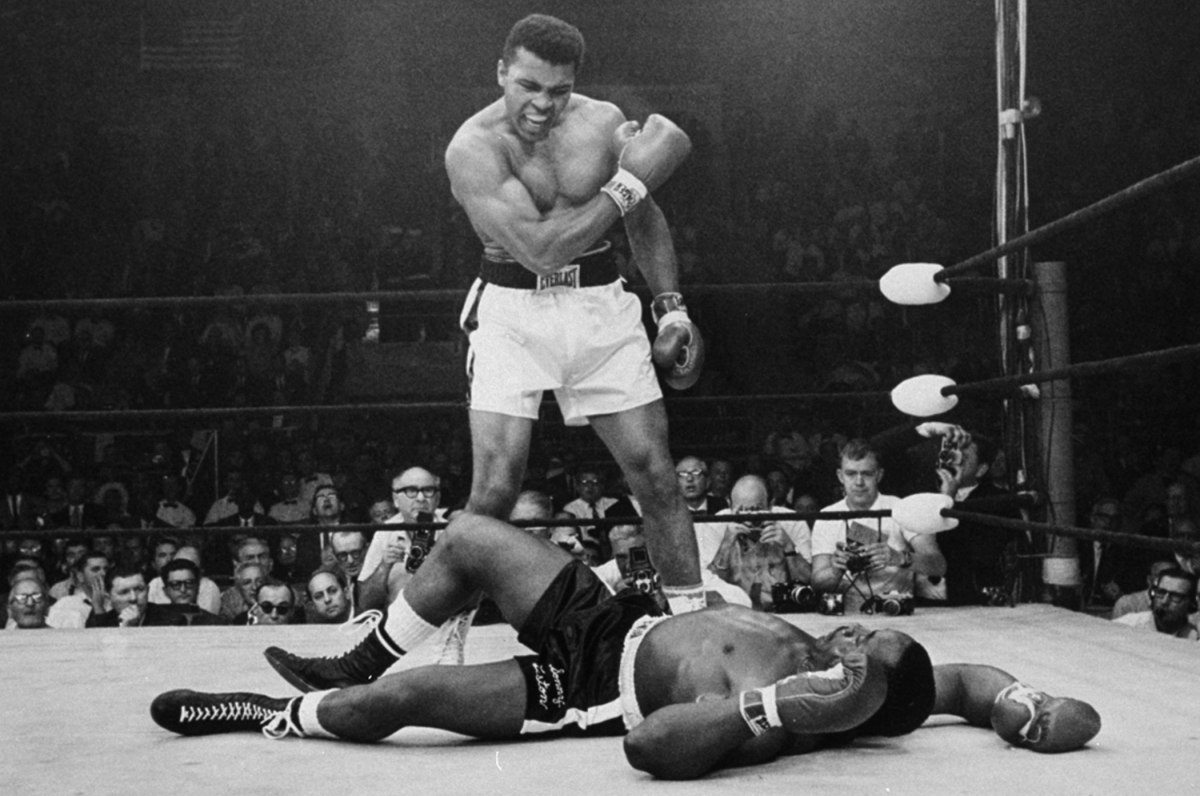

After winning his first 19 fights, including 15 knockouts, Clay received his first title shot on February 25, 1964, against reigning heavyweight champion Sonny Liston (1932-1970). Although he arrived in Miami Beach, Florida, a 7-1 underdog, the 22-year-old Clay relentlessly taunted Liston before the fight, promising to “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” and predicting a knockout. When Liston failed to answer the bell at the start of the seventh round, Clay was indeed crowned heavyweight champion of the world. In the ring after the fight, the new champ roared, “I am the greatest!”

At a press conference the next morning, Clay, who had been seen around Miami with controversial Nation of Islam member Malcolm X (1925-1965), confirmed the rumors of his conversion to Islam. On March 6, 1964, Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad (1897-1975) bestowed on Clay the name of Muhammad Ali.

Ali solidified his hold on the heavyweight championship by knocking out Liston in the first round of their rematch on May 25, 1965, and he defended his title eight more times. Then, with the Vietnam War raging, Ali showed up for his scheduled induction into the U.S. Armed Forces on April 28, 1967. Citing his religious beliefs, he refused to serve. Ali was arrested, and the New York State Athletic Commission immediately suspended his boxing license and revoked his heavyweight belt.

Convicted of draft evasion, Ali was sentenced to the maximum of five years in prison and a $10,000 fine, but he remained free while the conviction was appealed. Many saw Ali as a draft dodger, and his popularity plummeted. Banned from boxing for three years, Ali spoke out against the Vietnam War on college campuses. As public attitudes turned against the war, support for Ali grew. In 1970 the New York State Supreme Court ordered his boxing license reinstated, and the following year the U.S. Supreme Court overturned his conviction in a unanimous decision.

Muhammad Ali’s Return to the Ring

After 43 months in exile, Ali returned to the ring on October 26, 1970, and knocked out Jerry Quarry (1945-1999) in the third round. On March 8, 1971, Ali got his chance to regain his heavyweight crown against reigning champ Joe Frazier (1944-2011) in what was billed as the “Fight of the Century.” The undefeated Frazier floored Ali with a hard left hook in the final round. Ali got up but lost in a unanimous decision, experiencing his first defeat as a pro.

Ali won his next 10 bouts before being defeated by Ken Norton (1943-). He won the rematch six months later in a split decision and gained further revenge in a unanimous decision over Frazier in a non-title rematch. The victory gave the 32-year-old Ali a title shot against 25-year-old champion George Foreman (1949-). The October 30, 1974, fight in Kinshasa, Zaire, was dubbed the “Rumble in the Jungle.” Ali, the decided underdog, employed his “rope-a-dope” strategy, leaning on the ring ropes and absorbing a barrage of blows from Foreman while waiting for his opponent to tire. The strategy worked, and Ali won in an eighth-round knockout to regain the title stripped from him seven years prior.

Ali successfully defended his title in 10 fights, including the memorable “Thrilla in Manila” on October 1, 1975, in which his bitter rival Frazier, his eyes swollen shut, was unable to answer the bell for the final round. Ali also defeated Norton in their third meeting in a unanimous 15-round decision.

On February 15, 1978, an aging Ali lost his title to Leon Spinks (1953-) in a 15-round split decision. Seven months later, Ali defeated Spinks in a unanimous 15-round decision to reclaim the heavyweight crown and become the first fighter to win the world heavyweight boxing title three times.

After announcing his retirement in 1979, Ali launched a brief, unsuccessful comeback. However, he was overwhelmed in a technical knockout loss to Larry Holmes (1949-) in 1980, and he dropped a unanimous 10-round decision to Trevor Berbick (1954-2006) on December 11, 1981. After the fight, the 39-year-old Ali retired for good with a career record of 56 wins, five losses and 37 knockouts.

Muhammad Ali’s Later Years and Legacy

In 1984 Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson’s syndrome, possibly connected to the severe head trauma suffered during his boxing career. The former champion’s motor skills slowly declined, and his movement and speech were limited. In spite of the Parkinson’s, Ali remained in the public spotlight, traveling the world to make humanitarian, goodwill and charitable appearances. He met with Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein (1937-2006) in 1990 to negotiate the release of American hostages, and in 2002 he traveled to Afghanistan as a United Nations Messenger of Peace.

Ali had the honor of lighting the cauldron during the opening ceremonies of the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta. In 1999 Ali was voted the BBC’s “Sporting Personality of the Century,” and Sports Illustrated named him “Sportsman of the Century.” Ali was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in a 2005 White House ceremony, and in the same year the $60 million Muhammad Ali Center, a nonprofit museum and cultural center focusing on peace and social responsibility, opened in Louisville.

Ring Magazine named Ali “Fighter of the Year” five times, more than any other boxer, and he was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990. Ali has been married four times and has seven daughters and two sons. He married his fourth wife, Yolanda, in 1986. Ali died at the age of 74 on June 3, 2016.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Biography Online

Muhammad Ali Biography

“I’m not the greatest; I’m the double greatest. Not only do I knock ’em out, I pick the round. “

– Muhammad Ali

Ali was born in Louisville, Kentucky in 1942. He was named after his father, Cassius Marcellus Clay, Sr., (who was named after the 19th-century abolitionist and politician Cassius Clay). Ali would later change his name after joining the Nation of Islam. He subsequently converted to Sunni Islam in 1975.

Early boxing career

Standing at 6’3″ (1.91 m), Ali had a highly unorthodox style for a heavyweight boxer. Rather than the normal boxing style of carrying the hands high to defend the face, he instead relied on his quick feet and ability to avoid a punch. In Louisville, October 29, 1960, Cassius Clay won his first professional fight. He won a six-round decision over Tunney Hunsaker, who was the police chief of Fayetteville, West Virginia. From 1960 to 1963, the young fighter amassed a record of 19-0, with 15 knockouts. He defeated such boxers as Tony Esperti, Jim Robinson, Donnie Fleeman, Alonzo Johnson, George Logan, Willi Besmanoff, Lamar Clark (who had won his previous 40 bouts by knockout), Doug Jones, and Henry Cooper. Among Clay’s victories were versus Sonny Banks (who knocked him down during the bout), Alejandro Lavorante, and the aged Archie Moore (a boxing legend who had fought over 200 previous fights, and who had been Clay’s trainer prior to Angelo Dundee).

Despite these close calls against Doug Jones and Henry Cooper, he became the top contender for Sonny Liston’s title. In spite of Clay’s impressive record, he was not expected to beat the champion. The fight was to be held on February 25, 1964, in Miami, Florida. During the weigh-in before the fight, Ali frequently taunted Liston. Ali dubbed him “the big ugly bear”, and declared that he would “float like a butterfly and sting like a bee,” Ali was ready to dance around the ring, as he said, “Your hands can’t hit what your eyes can’t see.”

This was a typical buildup for Ali, who increasingly enjoyed playing to the crowd and creating a buzz before a fight. It was good news for fight promoters, who saw increased interest in any fight involving the bashful Ali.

Vietnam War

In 1964, Ali failed the Armed Forces qualifying test because his writing and spelling skills were inadequate. However, in early 1966, the tests were revised and Ali was reclassified 1A. He refused to serve in the United States Army during the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector, because “War is against the teachings of the Holy Koran. I’m not trying to dodge the draft. We are not supposed to take part in no wars unless declared by Allah or The Messenger. We don’t take part in Christian wars or wars of any unbelievers.” Ali also famously said,

Ali also famously said,

“I ain’t got no quarrel with those Vietcong” and “no Vietcong ever called me nigger.”

Ali refused to respond to his name being read out as Cassius Clay, stating, as instructed by his mentors from the Nation of Islam, that Clay was the name given to his slave ancestors by the white man.

“Cassius Clay is a slave name. I didn’t choose it and I don’t want it. I am Muhammad Ali, a free name – it means beloved of God – and I insist people use it when people speak to me and of me.”

By refusing to respond to this name, Ali’s personal life was filled with controversy. Ali was essentially banned from fighting in the United States and forced to accept bouts abroad for most of 1966.

From his rematch with Liston in May 1965, to his final defence against Zora Folley in March 1967, he defended his title nine times. Few other heavyweight champions in history have fought so much in such a short period.

Ali was scheduled to fight WBA champion Ernie Terrell in a unification bout in Toronto on March 29, 1966, but Terrell backed out and Ali won a 15-round decision against substitute opponent George Chuvalo. He then went to England and defeated Henry Cooper and Brian London by stoppage on cuts. Ali’s next defence was against German southpaw Karl Mildenberger, the first German to fight for the title since Max Schmeling. In one of the tougher fights of his life, Ali stopped his opponent in round 12.

Ali returned to the United States in November 1966 to fight Cleveland “Big Cat” Williams in the Houston Astrodome. A year and a half before the fight, Williams had been shot in the stomach at point-blank range by a Texas policeman. As a result, Williams went into the fight missing one kidney, 10 feet of his small intestine, and with a shrivelled left leg from nerve damage from the bullet. Ali beat Williams in three rounds.

On February 6, 1967, Ali returned to a Houston boxing ring to fight Terrell in what became one of the uglier fights in boxing. Terrell had angered Ali by calling him Clay, and the champion vowed to punish him for this insult. During the fight, Ali kept shouting at his opponent, “ What’s my name, Uncle Tom … What’s my name. ” Terrell suffered 15 rounds of brutal punishment, losing 13 of 15 rounds on two judges’ scorecards, but Ali did not knock him out. Analysts, including several who spoke to ESPN on the sports channel’s “Ali Rap” special, speculated that the fight only continued because Ali chose not to end it, choosing instead to further punish Terrell. After the fight, Tex Maule wrote, “It was a wonderful demonstration of boxing skill and a barbarous display of cruelty.”

Ali’s actions in refusing military service and aligning himself with the Nation of Islam made him a lightning rod for controversy, turning the outspoken but popular former champion into one of that era’s most recognisable and controversial figures. Appearing at rallies with Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad and declaring his allegiance to him at a time when mainstream America viewed them with suspicion — if not outright hostility — made Ali a target of outrage, and suspicion as well. Ali seemed at times to even provoke such reactions, with viewpoints that wavered from support for civil rights to outright support of separatism.

Near the end of 1967, Ali was stripped of his title by the professional boxing commission and would not be allowed to fight professionally for more than three years. He was also convicted for refusing induction into the army and sentenced to five years in prison. Over the course of those years in exile, Ali fought to appeal his conviction. He stayed in the public spotlight and supported himself by giving speeches primarily at rallies on college campuses that opposed the Vietnam War.

“Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs?”

– Muhammad Ali – explaining why he refused to fight in Vietnam

In 1970, Ali was allowed to fight again, and in late 1971 the Supreme Court reversed his conviction.

Muhammad Ali’s comeback

In 1970, Ali was finally able to get a boxing license. With the help of a State Senator, he was granted a license to box in Georgia because it was the only state in America without a boxing commission. In October 1970, he returned to stop Jerry Quarry on a cut after three rounds. Shortly after the Quarry fight, the New York State Supreme Court ruled that Ali was unjustly denied a boxing license. Once again able to fight in New York, he fought Oscar Bonavena at Madison Square Garden in December 1970. After a tough 14 rounds, Ali stopped Bonavena in the 15th, paving the way for a title fight against Joe Frazier.

The Fight of the Century

Ali and Frazier fought each other on March 8, 1971, at Madison Square Garden. The fight, known as ‘”The Fight of the Century”, was one of the most eagerly anticipated bouts of all time and remains one of the most famous. It featured two skilled, undefeated fighters, both of whom had reasonable claims to the heavyweight crown. The fight lived up to the hype, and Frazier punctuated his victory by flooring Ali with a hard left hook in the 15th and final round and won on points. Frank Sinatra — unable to acquire a ringside seat — took photos of the match for Life Magazine. Legendary boxing announcer Don Dunphy and actor and boxing aficionado Burt Lancaster called the action for the broadcast, which reached millions of people.

Frazier eventually won the fight and retained the title with a unanimous decision, dealing Ali his first professional loss. Despite an impressive performance, Ali may have still been suffering from the effects of “ring rust” due to his long layoff.

In 1973, after a string of victories over the top Heavyweight opposition in a campaign to force a rematch with Frazier, Ali split two bouts with Ken Norton (in the bout that Ali lost to Norton, Ali suffered a broken jaw).

Rumble in the Jungle

In 1974, Ali gained a match with champion George Foreman. The fight took place in Zaire (the Congo) – Ali wanted the fight to be there to help give an economic boost to this part of Africa. The pre-match hype was as great as ever.

“Floats like a butterfly, sting like a bee, his hands can’t hit what his eyes can’t see.”

– Muhammad Ali – before the 1974 fight against George Foreman

Against the odds, Ali won the rematch in the eighth round. Ali had adopted a strategy of wearing Foreman down though absorbing punches on the ropes – a strategy later termed – rope a dope.

This gave Ali another chance at the world title against Frazer

“It will be a killer, and a chiller, and a thriller, when I get the gorilla in Manila.”

– Ali before Frazer fight.

The fight lasted 14 rounds, with Ali finally proving victorious in the testing African heat.

Muhammad Ali in retirement

Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in the early 1980s, following which his motor functions began a slow decline. Although Ali’s doctors disagreed during the 1980s and 1990s about whether his symptoms were caused by boxing and whether or not his condition was degenerative, he was ultimately diagnosed with Pugilistic Parkinson’s syndrome. By late 2005 it was reported that Ali’s condition was notably worsening. According to the documentary ‘When We Were Kings’ when Ali was asked about whether he has any regrets about boxing due to his disability, he responded that if he didn’t box he would still be a painter in Louisville, Kentucky.

Speaking of his own Parkinson’s disease, Ali remarks how it has helped him to look at life in a different perspective.

“Maybe my Parkinson’s is God’s way of reminding me what is important. It slowed me down and caused me to listen rather than talk. Actually, people pay more attention to me now because I don’t talk as much.” “I always liked to chase the girls. Parkinson’s stops all that. Now I might have a chance to go to heaven.”

Muhammad Ali, BBC

Despite the disability, he remained a beloved and active public figure. Recently he was voted into Forbes Celebrity 100 coming in at number 13 behind Donald Trump. In 1985, he served as a guest referee at the inaugural WrestleMania event. In 1987 he was selected by the California Bicentennial Foundation for the U.S. Constitution to personify the vitality of the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights in various high profile activities. Ali rode on a float at the 1988 Tournament of Roses Parade, launching the U.S. Constitution’s 200th birthday commemoration. He also published an oral history, Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times with Thomas Hauser, in 1991. Ali received a Spirit of America Award calling him the most recognised American in the world. In 1996, he had the honour of lighting the flame at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, Georgia.

In 1999, Ali received a special one-off award from the BBC at its annual BBC Sports Personality of the Year Award ceremony, which was the BBC Sports Personality of the Century Award. His daughter Laila Ali also became a boxer in 1999, despite her father’s earlier comments against female boxing in 1978: “Women are not made to be hit in the breast, and face like that… the body’s not made to be punched right here [patting his chest]. Get hit in the breast… hard… and all that.”

On September 13, 1999, Ali was named “Kentucky Athlete of the Century” by the Kentucky Athletic Hall of Fame in ceremonies at the Galt House East.

In 2001, a biographical film, entitled Ali, was made, with Will Smith starring as Ali. The film received mixed reviews, with the positives generally attributed to the acting, as Smith and supporting actor Jon Voight earned Academy Award nominations. Prior to making the Ali movie, Will Smith had continually rejected the role of Ali until Muhammad Ali personally requested that he accept the role. According to Smith, the first thing Ali said about the subject to Smith was: “You ain’t pretty enough to play me”.

He received the Presidential Medal of Freedom at a White House ceremony on November 9, 2005, and the prestigious “Otto Hahn peace medal in Gold” of the United Nations Association of Germany (DGVN) in Berlin for his work with the US civil rights movement and the United Nations (December 17, 2005).

On November 19, 2005 (Ali’s 19th wedding anniversary), the $60 million non-profit Muhammad Ali Center opened in downtown Louisville, Kentucky. In addition to displaying his boxing memorabilia, the centre focuses on core themes of peace, social responsibility, respect, and personal growth.

According to the Muhammad Ali Center website in 2012,

“Since he retired from boxing, Ali has devoted himself to humanitarian endeavours around the globe. He is a devout Sunni Muslim, and travels the world over, lending his name and presence to hunger and poverty relief, supporting education efforts of all kinds, promoting adoption and encouraging people to respect and better understand one another. It is estimated that he has helped to provide more than 22 million meals to feed the hungry. Ali travels, on average, more than 200 days per year.”

Muhammad Ali died on 3 June 2016, from a respiratory illness, a condition that was complicated by Parkinson’s disease.

“Will they ever have another fighter who writes poems, predicts rounds, beats everybody, makes people laugh, makes people cry and is as tall and extra pretty as me?”

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Biography of Muhammad Ali ”, Oxford, UK – www.biographyonline.net . Last updated 3rd February 2018

Related pages

- Muhammad Ali Facts

- Muhammad Ali Quotes

Muhammad Ali and the Rise of an American Hero

Muhammad Ali and the Rise of an American Hero at Amazon

Muhammad Ali – The Whole Story

Muhammad Ali – The Whole Story at Amazon

External pages Pages

- www.ali.com – Official website

- www.maprc.com Muhammad Ali Parkinson Center (MAPC)

Muhammad Ali The Greatest Video

Muhammad Ali

American boxer and activist (1942–2016) / from wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, dear wikiwand ai, let's keep it short by simply answering these key questions:.

Can you list the top facts and stats about Muhammad Ali?

Summarize this article for a 10 year old

Muhammad Ali ( / ɑː ˈ l iː / ; [2] born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. ; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and activist. Nicknamed " the Greatest ", he is regarded as one of the most significant sports figures of the 20th century and is often regarded as the greatest heavyweight boxer of all time. He held the Ring magazine heavyweight title from 1964 to 1970. He was the undisputed champion from 1974 to 1978 and the WBA and Ring heavyweight champion from 1978 to 1979. In 1999, he was named Sportsman of the Century by Sports Illustrated and the Sports Personality of the Century by the BBC .

Born and raised in Louisville, Kentucky , he began training as an amateur boxer at age 12. At 18, he won a gold medal in the light heavyweight division at the 1960 Summer Olympics and turned professional later that year. He converted to Islam after 1961. He won the world heavyweight championship, defeating Sonny Liston in a major upset on February 25, 1964, at age 22. During that year, he denounced his birth name as a " slave name " and formally changed his name to Muhammad Ali. In 1966, Ali refused to be drafted into the military, owing to his religious beliefs and ethical opposition to the Vietnam War , and was found guilty of draft evasion and stripped of his boxing titles. He stayed out of prison while appealing the decision to the Supreme Court , where his conviction was overturned in 1971. He did not fight for nearly four years and lost a period of peak performance as an athlete. Ali's actions as a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War made him an icon for the larger counterculture of the 1960s generation, and he was a very high-profile figure of racial pride for African Americans during the civil rights movement and throughout his career. As a Muslim, Ali was initially affiliated with Elijah Muhammad 's Nation of Islam (NOI). He later disavowed the NOI, adhering to Sunni Islam .

He fought in several historic boxing matches, including his highly publicized fights with Sonny Liston, Joe Frazier (including the Fight of the Century , the biggest boxing event up until then), the Thrilla in Manila , and his fight with George Foreman in The Rumble in the Jungle . Ali thrived in the spotlight at a time when many boxers let their managers do the talking, and he became renowned for his provocative and outlandish persona. He was famous for trash-talking , often free-styled with rhyme schemes and spoken word poetry , and has been recognized as a pioneer in hip hop . He often predicted in which round he would knock out his opponent. As a boxer, Ali was known for his unorthodox movement, fancy footwork, head movement, and rope-a-dope technique, among others.

Outside boxing, Ali attained success as a spoken word artist, releasing two studio albums: I Am the Greatest! (1963) and The Adventures of Ali and His Gang vs. Mr. Tooth Decay (1976). Both albums received Grammy Award nominations. He also featured as an actor and writer, releasing two autobiographies. Ali retired from boxing in 1981 and focused on religion, philanthropy, and activism. In 1984, he made public his diagnosis of Parkinson's syndrome , which some reports attributed to boxing-related injuries, though he and his specialist physicians disputed this. He remained an active public figure globally, but in his later years made fewer public appearances as his condition worsened, and he was cared for by his family.

Culture History

Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (1942–2016), born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr., was an iconic American professional boxer and one of the most celebrated sports figures of the 20th century. Known for his unparalleled skills in the ring, charismatic personality, and outspoken stance on social and political issues, Ali became a three-time world heavyweight champion. Beyond his boxing achievements, he was a symbol of resilience, courage, and activism, leaving an indelible mark on both the sporting world and the broader cultural landscape.

Growing up in a racially segregated Louisville, Ali experienced the harsh realities of racial discrimination from an early age. His father, Cassius Clay Sr., was a sign painter, and his mother, Odessa Grady Clay, worked as a domestic helper. Despite the challenges of a segregated society, young Cassius showed promise as an athlete. He began boxing at the age of 12, under the guidance of police officer and boxing coach Joe Martin, who recognized his natural talent and fiery determination.

In 1960, at the age of 18, Cassius Clay won a gold medal in the light heavyweight division at the Rome Olympics. This victory marked the beginning of his rapid ascent in the boxing world. Following the Olympics, Clay turned professional and was guided by trainer Angelo Dundee. Known for his lightning-fast footwork, quick jabs, and unorthodox boxing style, he soon gained a reputation for being a force to be reckoned with in the ring.

In 1964, Cassius Clay faced the reigning heavyweight champion, Sonny Liston, in a highly anticipated bout. Clay, however, was not content with merely challenging Liston for the title; he proclaimed himself “The Greatest” and confidently predicted that he would win. True to his bold predictions, Clay defeated Liston in a stunning upset, becoming the youngest boxer to take the heavyweight title.

Shortly after this victory, Cassius Clay publicly announced his conversion to Islam and embraced the teachings of the Nation of Islam, a controversial move during a time of heightened racial tension in the United States . He changed his name to Muhammad Ali, explaining that Cassius Clay was his “slave name.” Ali’s affiliation with the Nation of Islam and his refusal to be drafted into the U.S. military during the Vietnam War sparked intense controversy and condemnation. He cited religious reasons for his refusal, famously stating, “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong.”

The boxing authorities reacted swiftly, stripping Ali of his heavyweight title and suspending him from professional boxing. This period of exile from the sport, lasting nearly three years, took a toll on Ali’s career. Yet, it also became a defining chapter in his life, as he remained steadfast in his convictions and fought for his beliefs.

In 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Ali’s conviction in a unanimous decision, recognizing his conscientious objection to the Vietnam War based on religious grounds. This legal victory paved the way for Ali’s return to the boxing ring. The iconic “Rumble in the Jungle” bout against George Foreman in 1974, held in Kinshasa, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), became a symbol of Ali’s resilience and strategic brilliance. Foreman was considered unbeatable, but Ali employed a tactic he termed the “rope-a-dope,” allowing Foreman to exhaust himself before launching a counterattack that led to Ali regaining the heavyweight title.

Ali’s career was marked by several epic battles, including the “Thrilla in Manila” against Joe Frazier in 1975, widely regarded as one of the greatest boxing matches in history. Ali’s ability to absorb punishment, his strategic prowess, and his charismatic personality outside the ring endeared him to fans worldwide.

Beyond his achievements in boxing, Ali’s impact extended to the realm of civil rights and social justice. He used his platform to advocate for racial equality, religious freedom, and the rights of oppressed people. Ali’s charisma, wit, and outspoken nature made him a cultural icon and a symbol of resistance during a time of significant social change.

Ali’s later years were marked by the visible toll that boxing had taken on his health. He was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 1984, a condition attributed to the repeated head trauma sustained during his boxing career. Despite the physical challenges, Ali remained active in philanthropy and humanitarian efforts. He traveled extensively, promoting peace, understanding, and humanitarian causes.

In 1996, Ali had the honor of lighting the Olympic cauldron at the Summer Games in Atlanta, a poignant moment that symbolized his enduring impact on both sports and society. His struggle with Parkinson’s disease did not diminish his spirit, and he continued to inspire countless individuals around the world.

Muhammad Ali passed away on June 3, 2016, at the age of 74. His legacy transcends the world of boxing, leaving an indelible mark on the broader cultural and social landscape. Ali’s life serves as a testament to the power of conviction, resilience, and the pursuit of justice in the face of adversity. His famous words, “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee,” continue to resonate as a mantra of strength and determination for generations to come.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Site Navigation

Muhammad ali (1942–2016).

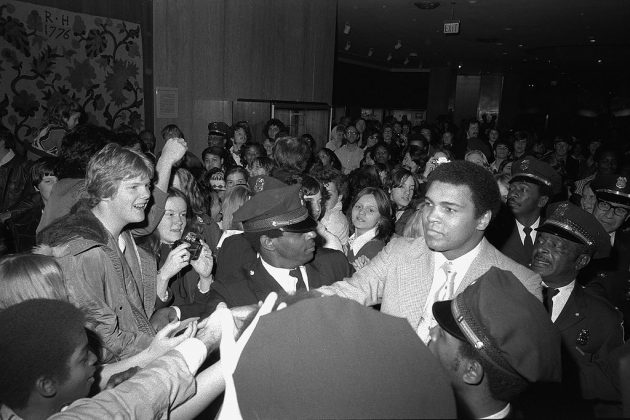

Visit of Muhammad Ali to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of History and Technology, now the National Museum of American History, March 17, 1976. During his visit he donated a pair of gloves and a robe to the museum for the “Nations of Nations” exhibition. Featured in TORCH, April 1976/Smithsonian Institution Archives. Click photo for article. (Photo by Richard K. Hofmeister)

“He who is not courageous enough to take risks will accomplish nothing in life.”–Muhammad Ali

Risk taker, sports figure and fearless social icon, Muhammad Ali, who died on June 4, is ever alive in the hearts of those who know him as the greatest boxer of the 20th century. His quotes and observations, like the one above, are legion. A quote by Shakespeare “To thine own self be true,” fits him well. The path he choose not only immortalized him to sports fans but endeared him to the general public. It was a path that led through the Smithsonian.

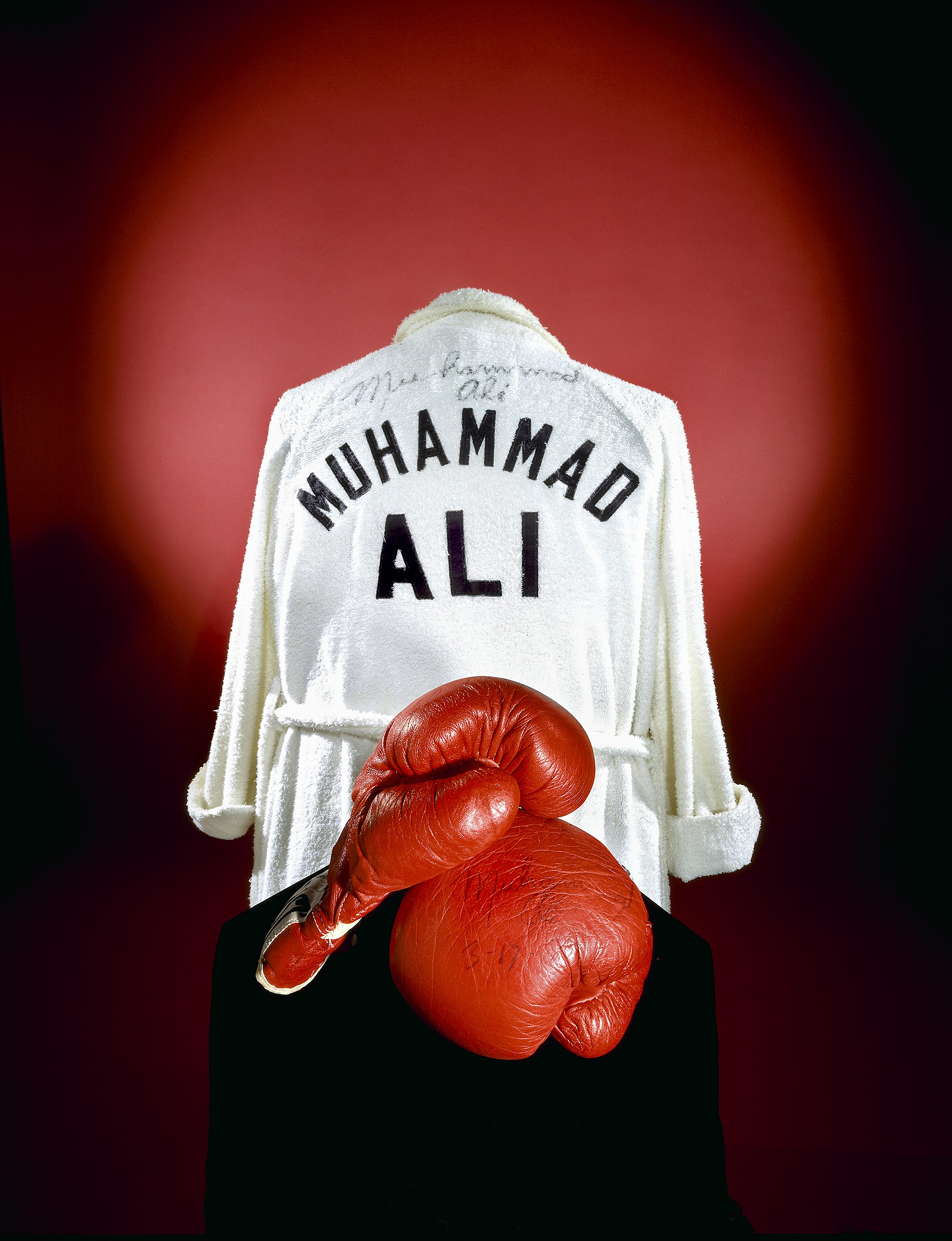

In 1976, the Smithsonian acquired Ali’s boxing gloves and robe for an exhibition on the American Bicentennial, “A Nation of Nations.” At the donation ceremony, before a crowd of reporters and cheering spectators, Ali predicted that his Everlast gloves would become “the most famous thing in this building.”

The Smithsonian’s Ali objects artifacts and portraits are a testament to Ali’s life. Muhammad Ali rose from humble beginnings to become one of the most famous men in the world. Ali’s complexity matched the spirit of the tumultuous 1960s. He was at once a boxing titan, a civil rights warrior, an anti-war protester, and a charismatic celebrity.

Over the years the National Portrait Gallery, the National Postal Museum, the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Museum of African American History and Culture have collected images and memorabilia of the boxer.

On the Portrait Gallery’s third-floor mezzanine is a 1981 painting of Ali from the museum’s permanent collection, “Cat’s Cradle,” by Henry C. Casselli, Jr.

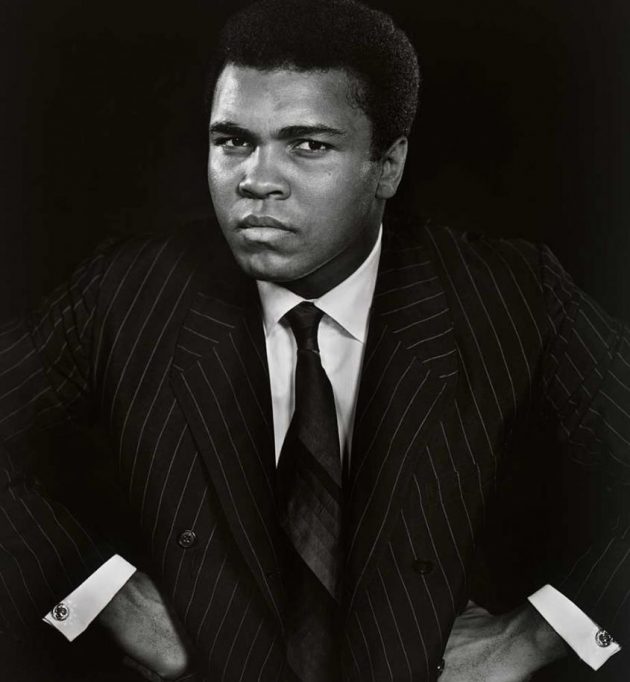

As a tribute to the man on the day of his passing, the Portrait Gallery installed a likeness that makes a statement about Ali the man. The boxer’s image, taken by photographer Yousuf Karsh in 1970, can be found near the north entrance on the first floor.

The charismatic Ali appeared on television, in commercials, and in a film about his life, and he used his worldwide fame for humanitarian efforts as well. Much more than an outstanding boxer, the media star became a symbol of courage, independence, and determination.

A few of many Muhammad Ali-related images and items at the Smithsonian include:

- Art & Design

- History & Culture

- Science & Nature

- Open Access

- Mobile Apps

The life of Muhammad Ali 1942-2016

As a boxer, Ali will be remembered as a three-time world heavyweight champion who won 56 bouts over a 21-year career.

New York – Of all the tributes being paid to Muhammad Ali, few can match the praise that the former boxer heaped upon himself.

Muhammad Ali was born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr on January 17, 1942, in Louisville Kentucky

Aged 22, he took on heavyweight champion Sonny Liston in Miami. He won and proclaimed to the world: “I am the world’s greatest!”

Ali was the first man to win heavyweight titles three times

Ali attended his first Nation of Islam meeting in 1959 and converted to Sunni Islam in 1975

In 1967, he famously refused to fight in Vietnam, citing religious reasons

Married four times, he had seven daughters and two sons

He was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 1984, at the age of 43

Ali died late on June 3, 2016, in a hospital in Arizona after being admitted with respiratory problems

Ali’s funeral will take place in Louisville

Ali is survived by his wife, the former Lonnie Williams, who knew him when she was a child, along with his nine children

Ali, in his own words, was the “prettiest, the most superior, most scientific, most skilfullest fighter in the ring”.

Keep reading

‘mma brought me closer to god’: biaggio ali walsh, muhammad ali’s grandson, dutch boxing hero who fought ali still riding punches in bulgaria, the black game changers of us sport, float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.

Elvis Presley was the 20th century’s king of Rock ‘n’ Roll, and Ali was the Elvis of Boxing, he once said.

Most of the time, Ali dispensed with comparisons or complex superlatives. He was, simply, “the Greatest”.

If anybody took this self-congratulation for arrogance, Ali had an answer ready. “It’s hard to be humble when you’re as great as I am,” he said.

He died on Friday aged 74, after a decades-long struggle with Parkinson’s disease – a slowly worsening brain disorder that never wholly subdued one of the sporting world’s biggest personalities.

As a boxer, he will be remembered as a three-time world heavyweight champion who won 56 bouts over a 21-year career.

READ MORE: Muhammad Ali quotes on boxing and racism

Ali also made headlines outside the ring with critiques of racism in the US, his conversion to Islam and a refusal to fight in the Vietnam War.

He was born in the American South of 1942 and the segregation era, taking his original name, Cassius Clay, from his father, a sign and mural painter. His mother, Odessa Clay, was a housemaid.

In 1954, it was Ali’s quick tongue that got him into boxing.

The skinny 12-year-old sought out local police officer Joe Martin to report his red bicycle as stolen in his home town of Louisville, Kentucky.

Ali said he would whip the thief who had pinched his Christmas gift. Martin – who also ran a boxing gym – said Ali had better learn how to fight to come good on his threat.

Six years later, he won a gold medal in the 175-pound division at the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome and launched his professional career.

Nation of Islam phase

A title fight against Sonny Liston won him fame in 1964. Ali was an underdog who became world heavyweight champion by pounding his rival to defeat in six rounds – a big upset in sports history.

Two days later, he shocked the US again by embracing the Nation of Islam – a religious group that seeks to improve life for blacks in the US, but has been criticised for black supremacist ideas.

He also dropped what he called his “slave name” and became Muhammad Ali.

Ali’s links with activist Malcolm X and his spiritual mentor, Elijah Muhammad, worried conservatives, but he was an inspiration for many.

“As a child, the first action figure my parents got me was of Muhammad Ali. For my generation, he was perhaps the largest and most influential pop culture icons for African-Americans and Muslims,” Dawud Walid, from the Council on American-Islamic Relations, an advocacy group, told Al Jazeera.

![biography of boxer muhammad ali Ali fighting heavyweight champion Joe Frazier in 1971 [Getty]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/2011118172440402734_8.jpeg)

“In the civil rights era, he stood against the discrimination we’ve all faced in the US. He crystallised that mindset of resistance and a feeling among many Muslims not to submit to stereotypes; that being Muslim is just as American as being Christian or Jewish.”

Ali risked his career – and his reputation – to oppose the Vietnam War. Citing religious beliefs, he refused to serve in the US srmy and was subsequently arrested for committing a felony. “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong,” he said.

The conflict was broadly popular in the US at that time, and Ali was stripped of his titles, had his boxing licence suspended and was found guilty of an offence at a 1967 trial. The US Supreme Court reversed the conviction four years later.

“He was ahead of the curve in calling the Vietnam War wrong and he doesn’t get enough credit for that,” Michael McPherson, director of the anti-war group, Veterans for Peace, told Al Jazeera.

“He was an African-American Muslim who criticised US foreign policy. It’s hard to do that today; but back then, black people had to prove their allegiance, patriotism and belief in America. I wish we had more people who speak out when something is wrong.”

Back in the ring in 1970, Ali continued to “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” against the likes of George Foreman and Joe Frazier.

He lost the Fight of the Century to Frazier at Madison Square Garden after 15 rounds in 1971, but beat him back four years later in the capital of the Philippines – the so-called Thrilla in Manila.

Rope-a-dope trick

Fans have questioned Ali’s style: he held his hands low and backed away from punches, rather than dodging and weaving.

His “rope-a-dope” trick of leaning back on the ropes to avoid blows helped him win a knockout victory against Foreman in a 1974 title fight – the Rumble in the Jungle – in Kinshasa, Zaire, now called the Democratic Republic of Congo.

As well as being able to take a punch, Ali fought with speed, courage and good footwork. He ranks among the greatest boxers of all time, alongside Sugar Ray Robinson, Joe Louis, Henry Armstrong and others.

He fought his final professional fight and married his fourth wife, Lonnie Williams, in the 1980s. Having left the hard-line Nation of Islam, Ali embraced the mainstream Sunni faith and remained politically active despite the onset of Parkinson’s.

Ralph Ali, Frazier & Foreman we were 1 guy. A part of me slipped away, "The greatest piece" https://t.co/xVKOc9qtub — George Foreman (@GeorgeForeman) June 4, 2016

He met Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein in 1990 and brokered the release of Americans who had been held hostage after the invasion of Kuwait. In 2011, he called on Iran to release the captive US hikers Shane Bauer and Josh Fattal.

One of Ali’s most celebrated moments came in 1996, when he lit the cauldron at the opening ceremony to the Atlanta Olympics. His willingness to appear despite a visibly twitching arm touched many in the crowd.

It was a “moment of infinite sadness, yet supreme majesty”, wrote Ken Rosenthal in The Baltimore Sun. Parkinson’s disease was “proving a more difficult opponent than Joe Frazier” for the champion.

The father-of-nine’s less-frequent television appearances showed how even the cleverest and strongest men are worn down by a brain illness.

“Parkinson’s sufferers say they can still think the things they thought before they had the disease – it just takes them a lot longer,” Peter Schmidt, who heads research programmes at the National Parkinson Foundation, told Al Jazeera.

“You can imagine how hard it was for Ali, who joked around so much and for whom timing was so important. That’s why he remained such an inspiration – even though he was so seriously affected, he was always joking and continued to have such an infectious personality.”

While the sporting world has had many champions, few can match Ali for charisma and swagger.

In his own words: “I won’t miss fighting, fighting will miss me.”

Follow James Reinl on Twitter: @jamesreinl

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Muhammad Ali, 1942-2016

Muhammad Ali Dies at 74: Titan of Boxing and the 20th Century

Muhammad ali: ‘what’s my name’, the three-time world champion boxer muhammad ali has died. current and former new york times reporters and columnists talk about their memories of him and how he became an international icon..

Ali: Well, as I understand, I’m Cassius Marcellus Clay, the sixth and my great-great grandfather was a Kentucky slave when he was named after some great Kentuckian, but Cassius Marcellus Clay is a great name in Kentucky. And uh, really, where, he was from, where it was all originated, I couldn’t tell ya, but since I reached a little fame in boxing, most people want to know where I’m-a from and uh, where did I get that name. But really, I haven’t really checked on that. So, I see that I’m gonna have to go look in the books Reporter: You have to look it up Ali: See what’s it all about now I’m getting the little interviews On screen interview with reporter He was born Cassius Clay Became MUHAMMAD ALI And IS WIDELY HAILED AS ONE OF THE GREATEST And most influential ATHLETES OF THE 20TH CENTURY. The THREE TIME HEAVYWEIGHT CHAMPION Possessed unrivaled speed and agility inside the ring And an unmatched wit and charisma outside of it. He would come to be celebrated all over the world - A symbol of tolerance and understanding But was militant and confrontational in his youth. HIS FIRST TITLE BOUT CAME IN 1964. FEW THOUGHT HE HAD MUCH OF A CHANCE Ali dancing in the ring / Ali shooting his mouth off outside of it Ali: I predict that tonight someone will die at ringside of shock! Lipsyte: In 1964, the champion was Sonny Liston. And he was absolutely unbeatable. Cassius Clay was a 7-1 underdog - which is enormous, prohibitive odds. The New York Times sent me down there with these instructions: As soon as I got to Miami, rent a car, drive back and forth between the arena where the fight was gonna’ be held and the nearest hospital so I would waste no time following Cassius Clay into intensive care. Shot of Liston fight (KO) / BUT CLAY DOMINATED THE FIGHT: HE ELUDED LISTON’S FISTS, AND BY THE SIXTH ROUND WAS HITTING THE CHAMPION VIRTUALLY AT WILL. Shots from fight (ANNOUNCERS) WHEN LISTON DIDN’T ANSWER THE BELL FOR THE SEVENTH ROUND, CLAY BECAME THE HEAVYWEIGHT CHAMPION OF THE WORLD. (ANNOUNCER) IT WAS CLEAR FROM THE VERY BEGINNING THAT CLAY WAS GOING TO BE A DIFFERENT KIND OF CHAMPION:- BRASH, OUTSPOKEN SOON AFTER HIS VICTORY, HE JOINED THE NATION OF ISLAM AND CHANGED HIS NAME TO MUHAMMAD ALI. BUT MANY PUBLICATIONS, INCLUDING THE NEW YORK TIMES CONTINUED TO CALL HIM CASSIUS. Shots from fight Lipsyte: I said to him, ‘Listen, sorry about this, but this is out of my control.’ And he patted me on the head and said, ‘Don’t worry, you’re just a little brother of the white power structure.’ Shots of “Cassius Clay” in NYT articles SOME ASKED IF HE MIGHT OFFICIALLY CHANGE IT AS A REPORTER DID IN THIS PRESS CONFERENCE CAPTURED BY KTVU NEWS CAMERAS. Reporter: You’ve thought about changing it legally to Muhammad? Ali: Legally? Le- How’s that, who would I have to Reporters: In court, the court. (laughter) Ali: Who would I have to face? Reporter: The judge. Ali: The judge is what color? Reporter: I don’t know. Ali: He’s white. Reporters: Probably. There are negro judges. Ali: So in other words, I’d have to ask a white man, ‘May I call myself Muhammad Ali, boss?’ On screen Lipsyte: He’s very sensitive about my rightful name. And in several very cruel fights, one with Floyd Patterson, one with Ernie Terrell, he tortured them. Didn’t knock them out when he could have, because he wanted to inflict more punishment, because they insisted on calling him Cassius Clay. On screen / shots from the two fights mentioned Ali: If Floyd dreamed he beat me, he’d apologize. He’d rather run through hell in a gasoline sport coat. On screen Lipsyte: He tortured Floyd. It was like a little boy picking the wings off a butterfly. And he would just, uh, he would just kind of punch Floyd, step back Shots from fight After Patterson, Ali defeated George Chuvalo in March 1966. And then Henry Cooper in a six round TKO in May. He knocked out Brian London in only three rounds in August, beat Carl Millenberger in 12 rounds in September, and defeated Cleveland Williams in three round technical knockout in November, in what many experts consider to be the most dominant performance in Ali’s career. Four months later, In a pre-fight with Howard Cosell and ABC sports Ali almost came to blows with Ernie Terrell. Shots from fights (Ali and Terrell argue) Lipsyte: Ernie Terrell, somehow got boxed into, you know, standing up for the establishment; and that was, you know, another terrible and ugly fight. This was the, mean and cruel streak. Shots from fight Rhoden: Terrell would not call him by his name, you wanna call him Cassius. And so what, he just punished him. (bell) He was like, ‘What’s my name? Howard Cosell: He said he’d humiliate him, I hardly think it’s necessary. Don’t you agree, Joe? “Joe”: (laughs) I don’t, I don’t know about that. I think that Clay can do what he wants to do in the ring. Shots from fight FINALLY, IN MARCH 1967, ALI DEFEATED ZORA FOLLEY. He had won 29 fights in six and a half years - ONE OF THE MOST EXTRAORDINARY RUNS IN HEAVYWEIGHT BOXING HISTORY. Although he didn’t know it at the time, IT WOULD BE THREE AND A HALF YEARS BEFORE HE FOUGHT AGAIN. WHEN ALI REFUSED INDUCTION INTO THE ARMED FORCES, THE STATE BOXING COMMISSIONS SUSPENDED HIM AND STRIPPED HIM OF HIS TITLE. Shots from fights Lipsyte: Wave after wave of TV reporter, radio reporter, they all came, you know, ‘You know in a few minutes, you’re gonna be, you know, in the front lines.’ And then black Muslims would come and they’d say, ‘Some cracka’ sergeant gonna’ drop a hand grenade down into your pants.’ Um, and he was wild, and he was exasperated. And late in the evening, I remember standing there, late in the evening, the last radio reporter comes and goes, ‘So champ, how do you feel about being re-classified and going to Vietnam? And then he said, ‘I ain’t got nothing against them viet cong.’ Then he spent the next couple of years backing that up. He refused to step forward to be drafted, he was stripped of his title, but he stood firm. Getty Archival / Lipsyte on screen Rhoden: The heavyweight champion of the world is telling people that you can take my belt, you can take my championship and that introduced a lot to courage, to honor, to valor, it was not just about running fast, jumping high, but what do you stand for? What are your morals, what are your principles? What’s stand would you take, what are you willing to risk? Rhoden on screen / Getty Archival Lipsyte: So for the next 3 and half years he couldn’t fight and he had to make a living mostly by um speaking engagements on college campuses. Ali at college speaking engagements Ali - “The purpose of war is to kill kill kill and keep on killing innocent people” Lipsyte: but you know in the course of that, in the Q and A’s after as they asked him political questions he was a quick study / he would kind of begin to understand you know the main threads of American life. Ali -“You my oppose when I want justice ...” Ali was never tried or even fined. He won his first appeal in 1970, When a federal court upheld his bid for a State license. He QUICKLY GOT BACK TO WORK BEATING JERRY QUARRY AND OSCAR BONAVENA. HIS CHANCE TO RECLAIM HIS TITLES CAME IN MARCH 1971, AGAINST HIS OLD FRIEND, JOE FRAZIER. IT WAS DUBBED THE FIGHT OF THE CENTURY. Shots from fights Sound UP - Ali and Frazier arguing Anderson: today now, 40 years later uh a lot of people because of their, their love of Ali, think Ali probably should have won that fight. Joe Frasier beat him up. / I can remember him saying, when a man gets me going that a real punch. And when he knocks me down that’s a REALL punch. And uh Joe Frasier had knocked him down. Anderson onscreen / Shots from fight IT WAS ALI’S FIRST PROFESSIONAL LOSS, But even though the decision was undisputed, He continued to talk trash about Joe Frazier Every chance he got. Wherever he might be. Ali defeated a dethroned Joe Frazier in January 1974, But his next championship bout wasn’t until ten months later When he squared off against GEORGE FOREMAN, IN A MATCH IN ZAIRE DUBBED, THE RUMBLE IN THE JUNGLE. Anderson: most people, including myself thought Foreman would demolish him. / there were 60, 000 people a soccer stadium in the middle of Africa. / yelling Ali boom-eye-aye. What that meant was Ali, kill him, because he was their guy. Anderson onscreen / Shots from fight Ali - 100,00 Africans screaming “Ali-boom-aye-yay .....” And he could- one reason was that Ali had told them that Foreman was a Belgian. For years it was the Belgian Congo. Belgium, that- was a colony for Belgium. So the name-the citizens there hated Belgium. So when Ali told them that Foreman was Belgian, he wasn’t of course, but when he told them that, they wanted to believe that Foreman was the enemy. Rhoden: that fight was just masterful. / he you know he just blew foreman’s mind you know. He completely as mush as one competitor could completely turn someone inside out- Ali had completely turned foreman inside out. Rhoden onscreen / Shots from fight Anderson: He would back off into the ropes and let Foreman pummel him. He would cover up like this, and foreman would just smash his ribs and everything. And then Ali would skirt away and bounce away, and finally Foreman just kind of punched himself out. Then Ali threw a right hand in the 8th round. And Foreman actually spun. Cause I was sitting there and looked up and Foreman spun and went down and just had no energy to get up. And Ali again now was the champion, with 3 years after he had lost the first year, and now suddenly everybody loved him. Anderson onscreen / Shots from fight After Foreman, Ali quickly dispatched Chuck Wepner and then Ron Lyle. A few months later, he flew to Malaysia To defend his tile against Joe Bugner. Anderson: (boxing gloves story) Lipsyte: (King of all Kings story) Lipsyte: people say well the great- he called himself the greatest, the prettiest that was just kind of box office. Eh, I don’t think so. I think that he, he uh, he did have this grandiosity about him and he, he was a narcissist. / there were some parts of him which can’t avoid / he was always available uh to fight. In some of the worse dictatorships in the world. Uh, he was enthralled to Don king, a criminal. Um there were kind of really kind of dark parts of him. But perhaps the darkest uh, was the a kind of a vicious attack on Joe Frazier. Calling him an uncle Tom and making fun of his looks. You know, calling him you know a gorilla, uh and I will, I will beat the gorilla in the thrilla in manila. FRAZIER SUPPORTED ALI’S RIGHT NOT TO SERVE IN THE VIETNAM WAR. HE TESTIFIED ON HIS FRIEND’S BEHALF BEFORE CONGRESS. EVEN LENT HIM MONEY WHEN ALI WASN’T FIGHTING. BUT WHAT STARTED AS A FRIENDLY RIVALRY IN THE RING BECAME SOMETHING ALTOGETHER DIFFERENT Frazier was hurt and angry WHEN THEY FACED OFF FOR THE THIRD TIME IN THE PHILIPPINES. Images of Fazier supporting Ali Anderson: The fight in Manila / god it had to be 100 degrees in that arena. And, and it was a brutal fight. Brutal I mean I, I called it an epic in brutality. And it was. I mean you couldn’t there was never a slow moment I mean the punches were brutal. And also by that time, four years after the first fight in the garden they were older and slower, they really couldn’t get out of each other’s way so every punch landed. / it stopped in the 15th round by Joe Frasier’s trainer because / his left eye had been closed and he couldn’t see- the trainer said he couldn’t see Ali’s right hand punches coming. So he stopped it. Even though he thought Frasier was ahead. Eddie Fudge was one of the great boxing trainers of all time and he stopped the fight because he didn’t; want Joe to get hurt. And maybe- who knows what. / One of the first questions, if not the first somebody said to him, what a brutal fight, what was it like in that ring? And I’ll never forget, all Ali said was “it was next to death.” Anderson onscreen / Shots from fight Frazier lost to Foreman again And then retired. Ali fought TEN MORE TIMES Defeating COOPMAN YOUNG DUNN NORTON EVANGELISTA SHAVERS He lost his title to Leon SPINKS in 1978 won it back later that year. And lost it for the last time to Larry HOLMES in 1980. But still Ali fought on He retired AFTER LOSING TO TREVOR BURBICK ON DECEMBER 11, 1981, A LITTLE OVER A MONTH BEFORE HIS 40th BIRTHDAY. TWO YEARS LATER, DAVE ANDERSON CAUGHT UP WITH HIM BEFORE ALI LEFT ON A GOOD-WILL TOUR. Shots from fights Anderson: He was probably a few pounds heavy, so he was- was going through some training, just light training. But something to get the weight off. In a gym in Miami, his great trainer Angelo Dundee was with him. And then afterwards we spoke- there were about 4 or 5 writers there and I remember that’s the first time I noticed he was slurring his words. I mean it was very uh very apparent. You couldn’t miss it. / to get, get the readers’ appreciation of how serious that was. I put the words together. / I mean it was, it was sad to hear him do that. And as we all know it got worse and worse and worse and worse. Anderson onscreen / image from NYT article of words running together ALI’S DECLINE WAS AS RAPID AS IT WAS DRAMATIC. HE APPEARED IN PUBLIC LESS AND LESS FREQUENTLY AS TIME WENT ON, BUT DESPITE HIS OBVIOUS DIFFICULTIES, HE NEVER LOST HIS SPARK Misc public appearances / Atlanta Olympics Rhoden: I saw him was at the Olympics in Sydney Australia, by this time the Parkinson’s it, it began to ravish him. But I remember meeting him uh, at some event and it was again it was a small gathering and so um, you know, I introduced myself- re-introduced myself to him. And I said, he said- by this time- he said “what, what’s your name?” and I said my name is Bill Rhoden. He said no, no, what’s your real name? Stills of Sydney olympics Ali: Muhammad means one who’s worthy of all praises and one who’s praise worthy and Ali means the most high, but Clay only meant only dirt with no ingredients, see. Ali onscreen Ali: “what’s my name!?” Patterson or turell fight

By Robert Lipsyte

- June 4, 2016

Muhammad Ali , the three-time world heavyweight boxing champion who helped define his turbulent times as the most charismatic and controversial sports figure of the 20th century, died on Friday in a Phoenix-area hospital. He was 74.

His death was confirmed by Bob Gunnell, a family spokesman. The cause was septic shock, a family spokeswoman said.

Ali, who lived near Phoenix, had had Parkinson’s disease for more than 30 years. He was admitted to the hospital on Monday with what Mr. Gunnell said was a respiratory problem.

Ali was the most thrilling if not the best heavyweight ever, carrying into the ring a physically lyrical, unorthodox boxing style that fused speed, agility and power more seamlessly than that of any fighter before him.

But he was more than the sum of his athletic gifts. An agile mind, a buoyant personality, a brash self-confidence and an evolving set of personal convictions fostered a magnetism that the ring alone could not contain. He entertained as much with his mouth as with his fists, narrating his life with a patter of inventive doggerel. ( “Me! Wheeeeee!” )