- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

Become an FT subscriber

Limited time offer save up to 40% on standard digital.

- Global news & analysis

- Expert opinion

- Special features

- FirstFT newsletter

- Videos & Podcasts

- Android & iOS app

- FT Edit app

- 10 gift articles per month

Explore more offers.

Standard digital.

- FT Digital Edition

Premium Digital

Print + premium digital.

Then $75 per month. Complete digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Cancel anytime during your trial.

- 10 additional gift articles per month

- Global news & analysis

- Exclusive FT analysis

- Videos & Podcasts

- FT App on Android & iOS

- Everything in Standard Digital

- Premium newsletters

- Weekday Print Edition

Complete digital access to quality FT journalism with expert analysis from industry leaders. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- Everything in Print

- Everything in Premium Digital

The new FT Digital Edition: today’s FT, cover to cover on any device. This subscription does not include access to ft.com or the FT App.

Terms & Conditions apply

Explore our full range of subscriptions.

Why the ft.

See why over a million readers pay to read the Financial Times.

International Edition

Spring trend report: Shop skin solutions and fashion problem solvers — from $9

- TODAY Plaza

- Share this —

- Watch Full Episodes

- Read With Jenna

- Inspirational

- Relationships

- TODAY Table

- Newsletters

- Start TODAY

- Shop TODAY Awards

- Citi Music Series

- Listen All Day

Follow today

More Brands

- On The Show

Teachers sound off on ChatGPT, the new AI tool that can write students’ essays for them

Teachers are talking about a new artificial intelligence tool called ChatGPT — with dread about its potential to help students cheat, and with anticipation over how it might change education as we know it.

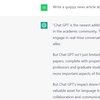

On Nov. 30, research lab OpenAI released the free AI tool ChatGPT , a conversational language model that lets users type questions — “What is the Civil War?” or “Who was Leonardo da Vinci?” — and receive articulate, sophisticated and human-like responses in seconds. Ask it to solve complex math equations and it spits out the answer, sometimes with step-by-step explanations for how it got there.

According to a fact sheet sent to TODAY.com by OpenAI, ChatGPT can answer follow-up questions, correct false information, contextualize information and even acknowledge its own mistakes.

Some educators worry that students will use ChatGPT to get away with cheating more easily — especially when it comes to the five-paragraph essays assigned in middle and high school and the formulaic papers assigned in college courses. Compared with traditional cheating in which information is plagiarized by being copied directly or pasted together from other work, ChatGPT pulls content from all corners of the internet to form brand new answers that aren't derived from one specific source, or even cited.

Therefore, if you paste a ChatGPT-generated essay into the internet, you likely won't find it word-for-word anywhere else. This has many teachers spooked — even as OpenAI is trying to reassure educators .

"We don’t want ChatGPT to be used for misleading purposes in schools or anywhere else, so we’re already developing mitigations to help anyone identify text generated by that system," an OpenAI spokesperson tells TODAY.com "We look forward to working with educators on useful solutions, and other ways to help teachers and students benefit from artificial intelligence."

Still, #TeacherTok is weighing in about potential consequences in the classroom.

"So the robots are here and they’re going to be doing our students' homework,” educator Dan Lewer said in a TikTok video . “Great! As if teachers needed something else to be worried about.”

“If you’re a teacher, you need to know about this new (tool) that students can use to cheat in your class,” educational consultant Tyler Tarver said on TikTok .

“Kids can just tell it what they want it to do: Write a 500-word essay on ‘Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows,’” Tarver said. “This thing just starts writing it, and it looks legit.”

Taking steps to prevent cheating

ChatGPT is already being prohibited at some K-12 schools and colleges.

On Jan. 4, the New York City Department of Education restricted ChatGPT on school networks and devices "due to concerns about negative impacts on student learning, and concerns regarding the safety and accuracy of content," Jenna Lyle, a department spokesperson, tells TODAY.com. "While the tool may be able to provide quick and easy answers to questions, it does not build critical-thinking and problem-solving skills, which are essential for academic and lifelong success."

A student who attends Lawrence University in Wisconsin tells TODAY.com that one of her professors warned students, both verbally and in a class syllabus, not to use artificial intelligence like ChatGPT to write papers or risk receiving a zero score.

And last month, a student at Furman University in South Carolina got caught using ChatGPT to complete a 1,200-word take-home exam on the 18th century philosopher David Hume.

“The essay confidently and thoroughly described Hume’s views on the paradox of horror in (ways) that were thoroughly wrong,” Darren Hick, an assistant professor of philosophy, explained in a Dec. 15 Facebook post . “It did say some true things about Hume, and it knew what the paradox of horror was, but it was just bullsh--ting after that.”

Hick tells TODAY.com that traditional cheating signs — for example, sudden shifts in a person’s writing style — weren’t apparent in the student’s essay.

To confirm his suspicions, Hick says he ran passages from the essay through a separate OpenAI detector, which indicated the writing was AI-generated. Hick then did the same thing with essays from other students. That time around, the detector suggested that the essays had been written by human beings.

Eventually, Hick met with the student, who confessed to using ChatGPT. She received a failing grade for the class and faces further disciplinary action.

“I give this student credit for being updated on new technology,” says Hick. “Unfortunately, in their case, so am I.”

Getting at the heart of teaching

OpenAI acknowledges that its ChatGPT tool is capable of providing false or harmful answers. OpenAI Chief Executive Officer Sam Altman tweeted that ChatGPT is meant for “ fun creative inspiration ” and that “ it’s a mistake to be relying on it for anything important right now.”

Kendall Hartley, an associate professor of educational technology at the University of Las Vegas, Nevada, notes that ChatGPT is "blowing up fast," presenting new challenges for detection software like iThenticate and TurnItIn , which teachers use to cross-reference student work to material published online.

Still, even with all the concerns being raised, many educators say they are hopeful about ChatGPT's potential in the classroom.

When you think about the amazing teachers you’ve had, it’s likely because they connected with you as a student. That won’t change with the introduction of AI.”

Tiffany Wycoff, a former school principal

"I'm excited by how it could support assessment or students with learning disabilities or those who are English language learners," Lisa M. Harrison, a former seventh grade math teacher and a board of trustee for the Association for Middle Level Education , tells TODAY.com. Harrison speculates that ChatGPT could support all sorts of students with special needs by supplementing skills they haven’t yet mastered.

Harrison suggests workarounds to cheating through coursework that requires additional citations or verbal components. She says personalized assignments — such as asking students to apply a world event to their own personal experiences — could deter the use of AI.

Educators also could try embracing the technology, she says.

"Students could write essays comparing their work to what's produced by ChatGPT or learn about AI," says Harrison.

Tiffany Wycoff, a former elementary and high school principal who is now the chief operating officer of the professional development company Learning Innovation Catalyst (LINC), says AI offers great potential in education.

“Art instructors can use image-based AI generators to (produce) characters or scenes that inspire projects," Wycoff tells TODAY.com. "P.E. coaches could design fitness or sports curriculums, and teachers can discuss systemic biases in writing.”

Wycoff went straight to the source, asking ChatGPT, "How will generative AI affect teaching and learning in classrooms?" and published a lengthy answer on her company's blog .

According to ChatGPT's answer, AI can give student feedback in real time, create interactive educational content (videos, simulations and more), and create customized learning materials based on individual student needs.

The heart of teaching, however, can't be replaced by bots.

"When you think about the amazing teachers you’ve had, it’s likely because they connected with you as a student," Wycoff says. "That won’t change with the introduction of AI."

Tarver agrees, telling TODAY.com, "If a student is struggling and then suddenly gets a 98 (on a test), teachers will know."

"And if students can go in and type answers in ChatGPT," he adds, "we're asking the wrong questions.”

Elise Solé is a writer and editor who lives in Los Angeles and covers parenting for TODAY Parents. She was previously a news editor at Yahoo and has also worked at Marie Claire and Women's Health. Her bylines have appeared in Shondaland, SheKnows, Happify and more.

ChatGPT was tipped to cause widespread cheating. Here's what students say happened

Science ChatGPT was tipped to cause widespread cheating. Here's what students say happened

As teachers met before the start of the 2023 school year, there was one big topic of conversation: ChatGPT.

Education departments banned students from accessing the artificial intelligence (AI) writing tool, which could produce essays, complete homework, and cheat on take-home assignments.

Some experts said schools would be swamped by a wave of cheating.

And then? Well, school continued.

The expected wave never broke. Or if it did, it was difficult to detect.

Many teachers said they strongly suspected students were cheating, but it was hard to tell for sure.

Meanwhile, some schools went in the opposite direction, embracing the new AI tools. Principals said students needed to learn how to use a technology that would probably define their futures.

But there was one perspective missing in all this: that of the students themselves.

As the school year drew to a close, we spoke to Year 11 and 12 students about how they actually ended up using generative AI tools.

Overall, these are stories from a historic moment, and an insight into the future of education. This is the first year where high school students could easily access high quality AI writing tools.

Here's what they had to say.

'The chatbot could smash it out in seconds'

Some were initially curious, but also cautious.

Some used it once then stopped. Others kept going.

Some got caught, but many didn't.

For Eric, who asked to remain anonymous, the arrival of ChatGPT in the summer of 2022–23 was a mixed blessing.

To stop students using AI to cheat on take-home assignments, his school switched to more in-class assessments.

But Eric, who has ADHD, struggles to concentrate in exams.

"That sort of crippled my chances at doing great in school," he says.

"Exams are the death of me."

But the new AI writing tool had its uses. In term one, he experimented with cheating, using ChatGPT to write a take-home geography assignment (though it didn't count towards his HSC).

He wasn't caught and got a decent grade.

Next, he gave ChatGPT his homework.

"It's just meaningless, monotonous work. And, you know, the chatbot could just smash it out in seconds."

Eric estimates that, over the course of 2023, ChatGPT wrote most of his homework.

"So around 60 per cent of my homework was written by ChatGPT," he says.

AI cheating creates divide among classmates

Students at other schools told similar stories.

Chrysoula, a Year 11 student in Sydney, initially used ChatGPT "very often to complete homework I deemed just tedious".

A lot of her classmates were doing the same, she says.

"Any time someone read a good answer out in class discussions, there was someone leaning over whispering 'Chat[GPT]?'

"Everyone doubted the authenticity of everyone's answers."

But as the year drew on, Chrysoula found her "critical and analytical thinking was slightly impaired".

"I was beginning to form a dependence on the AI to feed me the knowledge to rote learn."

Worried about AI harming her learning abilities, Chrysoula blocked herself from accessing the ChatGPT website.

The students who are still cheating are easy to spot, she says.

They often waste time in class and leave coursework to complete at home, when they can access AI tools. Their essays overuse words that ChatGPT favours, like "profound", or "metaphors for things like tapestries".

"They even hand in entire assessments written entirely by AI."

Phil, a Year 12 student at a different high school, also sees a divide that's formed among his classmates, based on how much each student uses AI to do their coursework.

His school allows students to use ChatGPT for ideas and research but not to directly write assessments.

But many students still cheat on take-home assignments, Phil says. He's worried they "aren't learning anything" and their poor performance in the HSC exams will ultimately hurt his ATAR.

"There's a significant population of the school who just aren't doing any work, and that drives us down because of how the ATAR system works."

Harry, a Year 11 student at another school, uses ChatGPT for some homework, but not for assignments.

His reason? The AI's answers aren't good enough.

"When you want to get the top marks, I'd say that's when you do want to use your own brain and you do want to critically think."

How common is AI cheating in schools?

Many of the high school students we spoke with weren't using AI to cheat, even though they could get away with it.

Whether this is representative of students in general is hard to say, as there's very little reliable data on cheating rates.

But at least one survey suggests that rates of AI cheating among students may be lower than generally assumed.

In mid-2023, the Centre for Democracy and Technology asked US high school students how much they used generative AI tools to do their coursework, and then compared this with the estimates of teachers and parents.

Kristin Woelfel, a co-author of the report , says teachers and parents consistently overestimate how many students use AI to cheat.

"While 58 per cent of students report having used generative AI in the past year, only 19 per cent of that group reports using it to write and submit papers," she says.

She says the survey data doesn't support the inflammatory predictions about cheating made at the start of the year.

"Students are primarily using generative AI for personal reasons rather than academic."

But Kane Murdoch, head of academic integrity at Macquarie University, says that even if the rate of AI cheating is low now, it's likely to go up.

He believes students will gain confidence, and learn how to use AI to automate more of their coursework.

"It could be 2023 was the year they dipped their toe in the water, but 2024 and moving ahead you’ll get increasingly large body parts into the pool.

"And soon enough they’ll be in the deep end."

Banning AI cheating hasn't worked

Many of the students we spoke to say teachers have little power to stop them from using AI tools for homework or assignments.

The past year proved blocking access to AI tools, as well as detecting AI-written coursework, was ineffective.

Students described numerous ways of evading the blocks on accessing ChatGPT on school computers, or through a school's Wi-Fi network.

They also told how they copied their ChatGPT-written answers into other AI tools, designed to confuse the schools' AI-detection software.

"Nearly every AI detector I've come across is inaccurate," Chrysoula says.

Mr Murdoch agrees.

"There's lot of skepticism about the efficacy of detection — and I'm among those who are skeptical."

He says educators were reluctant to rely on flawed plagiarism-detection tools to accuse a student of cheating.

"As an investigator [of cheating] I'm unwilling to accept the detectors word on it," he says.

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI has warned that there is no reliable way for educators to work out if students are using ChatGPT.

Several major universities in the US have turned off AI detection software, citing concerns over accuracy and a fear of falsely accusing students of using AI to cheat.

Mr Murdoch says Australian universities are also wary of relying on detection software.

But they disagree over what to do next. Some believe that better detection is the answer, while others are pushing for a change to the way learning is assessed.

"Programmatic" assessment, such as interviews and practical exams, may be one answer.

"It would mean we don't assess as much, and what we do assess we can actually hang our hat on," Mr Murdoch says.

"It's more like turning the ship in a very different direction rather than a slight course change.

"It's a much more difficult thing to grapple with."

Schools may go from banning bots to letting them teach

While the impact of AI on students has won most of the public attention, some education experts say the bigger story of 2023 may be how this technology changes the work of teaching.

Over the course of the year, schools have broadly gone from banning the technology to cautiously embracing it.

In February, state and federal education ministers slapped a year-long ban on student use of AI at state- and government-run schools.

Then, in October, the ministers agreed to lift the ban from term one next year.

The announcement brought public schools more in line with the approach of private and Catholic schools.

Federal education minister Jason Clare said at the time that "ChatGPT was not going away".

"We've got to learn how to use it," he said.

"Kids are using it right across the country ... we're playing catch-up."

But some observers are worried this new embrace of AI will replace in-person, teacher-led instruction.

The education industry is now promoting an idea of "platformisation", says Lucinda McKnight, a digital literacy expert at Deakin University.

"This is the idea that bots deliver education. The teacher shortage is solved by generative AI."

Custom-built chatbots, personalised for each student and loaded with the relevant curriculum, would teach, encourage and assess. Teachers would be experts in teaching , rather than the subject being taught.

But robo-classrooms like this have their drawbacks, Dr McKnight says.

Interacting with (human) teachers plays an important part in a child's emotional and social development.

"It's not the robots that are the problem, it's the fact students are going to be treated like robots," she says.

Macquarie University's Kane Murdoch says education institutions made a series of kneejerk reactions and false starts, such as the ChatGPT ban, in response to emergent AI technology in 2023.

Next year will see them make big changes, he predicts.

He's concerned that AI cheating will ultimately devalue educational qualifications.

"We can't expect this to go away. It is a game changer — it is existential," he says.

"If the public lose faith in what we do, we lose."

Student accounts suggest that, although not all want to cheat when they can, many are happy to automate tasks they see as rote learning rather than true tests of knowledge.

For Eric, who used ChatGPT to do most of his homework this year, the AI tool provided a shortcut through an already flawed system.

"I would have had such a worse time this year if ChatGPT wasn't prominent," he says.

"I think it would be very difficult for you to find a student that was sitting the HSC right now that hasn't used it for something."

Listen to the full story of how students used AI in 2023 and subscribe to RN Science Friction .

Science in your inbox

- X (formerly Twitter)

Related Stories

'bigger than the pandemic': this new ai tool promises to disrupt student assessment.

'I'm seriously considering ChatGPT': Uni staff have thousands of words to read when marking student papers

What is ChatGPT and how will it change the world?

- Artificial Intelligence

- Science and Technology

ChatGPT and cheating: 5 ways to change how students are graded

Professor of Education Governance and Policy Analysis, Brock University

Associate Dean, School of Graduate Studies & Professor, Faculty of Education, Queen's University, Ontario

Pro Vice-Chancellor of Te Wānanga Toi Tangata Division of Education; Professor of Measurement, Assessment and Evaluation, University of Waikato

Disclosure statement

Louis Volante receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC).

Don A. Klinger receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and the New Zealand Qualifications Authority.

Christopher DeLuca does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Queen's University, Ontario provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation CA.

Queen's University, Ontario and Brock University provide funding as members of The Conversation CA-FR.

University of Waikato provides funding as a member of The Conversation NZ.

University of Waikato provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

Brock University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA.

View all partners

- Bahasa Indonesia

Universities and schools have entered a new phase in how they need to address academic integrity as our society navigates a second era of digital technologies , which include publicly available generative artificial intelligence (AI) like ChatGPT. Such platforms allow students to generate novel text for written assignments .

While many worry these advanced AI technologies are ushering in a new age of plagiarism and cheating , these technologies also introduce opportunities for educators to rethink assessment practices and engage students in deeper and more meaningful learning that can promote critical thinking skills.

We believe the emergence of ChatGPT creates an opportunity for schools and post-secondary institutions to reform traditional approaches to assessing students that rely heavily on testing and written tasks focused on students’ recall, remembering and basic synthesis of content.

Cheating and ChatGPT

Estimates of cheating vary widely across national contexts and sectors .

Sarah Elaine Eaton, an expert who studies academic integrity, cautions cheating may be under-reported : she has estimated that at Canadian universities, 70,000 students buy cheating services every year.

How the recent launch of ChatGPT by OpenAI will impact cheating in both compulsory and higher education settings is unknown, but how this evolves may depend on whether or not institutions retain or reform traditional assessment practices.

Evading plagiarism detection software?

The ability of popular plagiarism detection tools to identify cheating using ChatGPT to generate assignments remains a challenge.

A recent study , not yet peer reviewed, found that 50 essays generated using ChatGPT produced sophisticated texts that were able to evade the traditional plagiarism check software.

Given that ChatGPT reached an estimated 100 million monthly active users in January, just two months after its launch, it is understandable why some have argued AI applications such as ChatGPT will spur enormous changes in contemporary schooling.

Policy responses to AI and ChatGPT

Not surprisingly, there are opposing views on how to respond to ChatGPT and other AI language models.

Some argue educators should embrace AI as a valuable technological tool, provided applications are cited correctly .

Others believe more resources and training are required so educators are better able to catch instances of cheating.

Still others, such as New York City’s Department of Education, have resorted to blocking AI applications such as ChatGPT from devices and networks .

Forward-thinking assessment

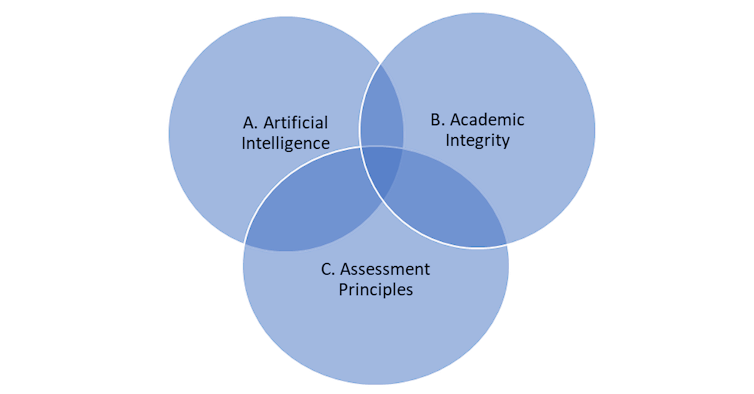

The figure below depicts three critical elements of a forward-thinking assessment system. Although each element could be elaborated, our focus is in offering educators a series of strategies that will allow them to maintain academic standards and promote authentic learning and assessment in the face of current and future AI applications.

Teachers and university professors have relied heavily on “one and done” essay assignments for decades. Essentially, a student is assigned or asked to pick a generic essay topic from a list and submit their final assignment on a specific date.

Such assignments are particularly susceptible to new AI applications, as well as contract cheating — whereby a student buys a completed essay. Educators now need to rethink such assignments. Here are some strategies.

1. Consider ways to incorporate AI in valid assessment.

It’s not useful or practical for institutions to outright ban AI and applications like ChatGPT.

AI has already been incorporated into some university classrooms . We believe AI technologies must be selectively integrated so that students are able to reflect on appropriate uses and connect their reflections to learning competencies.

For example, Paul Fyfe, an English professor who teaches about how humans interact with data describes a “pedagogical experiment” in which he required students to take content from text-generating AI software and weave this content into their final essay.

Students were then asked to confront the availability of AI as a writing tool and reflect on the ethical use and evaluation of language modes.

2. Engage students in setting learning goals.

Ensuring students understand how they will be graded is key to any good assessment system.

Inviting students to collaboratively establish learning goals and criteria for the task, with consideration for the role of AI software, would help students to evaluate and judge appropriate contexts in which AI can work as a learning tool.

Read more: Unlike with academics and reporters, you can't check when ChatGPT's telling the truth

3. Require students to submit drafts for feedback.

Although students should still complete essay assignments, research into academic integrity policy in response to generative AI suggests students should be required to submit drafts of their work for review and feedback. Apart from helping to detect plagiarism, this kind of “formative assessment” practice is positive for guiding student learning .

Feedback can be offered by the teacher or by students themselves. Peer- and self-feedback can serve to critically evaluate work in progress (or work generated by AI software).

4. Grade subcomponents of the task.

Students could receive a grade for each subcomponent — including their involvement in feedback processes. They would also be evaluated in relation to how well they incorporated and attended to the specific feedback provided.

The assignment becomes bigger than a final essay, it becomes a product of learning, where students’ ideas are evaluated from development to final submission.

5. Move to more authentic assessments or include performance elements.

Good assessment practice involves an educator observing student learning across multiple contexts.

For example, educators can invite students to present their work, discuss an essay in a conference format or share a video articulation or an artistic representation. The aim here is to encourage students to share their learning through an alternative format. An important question to ask is whether or not you need the essay component at all? Is there a more authentic way to effectively assess student learning?

Authentic assessments are those that relate content to context. When students are asked to do this, they must apply knowledge in more practical settings, often making AI tools less helpful.

For help in rethinking assessment practices towards more authentic and alternative approaches, educators can consider taking the free course, Transforming Assessment: Strategies for Higher Education .

Improve benefits for students

Collectively, these suggestions may be more time-consuming, particularly in larger undergraduate classes.

But they do provide greater learning and synergy between forms of assessment that benefit students: formative assessment to guide teaching and learning, and “summative assessment,” primarily used for grading and evaluation purposes.

AI is here and here to stay, and we must embrace it as part of our learning environment. Incorporating AI into how we assess student learning will yield more reliable assessment processes and valid and valued assessment outcomes.

- Artificial intelligence (AI)

- Universities

- Digital age

- Academic integrity

- University study

- university policy

- Student assessment

- post-secondary study

Biocloud Project Manager - Australian Biocommons

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

Deputy Editor - Technology

A professor accused his class of using ChatGPT, putting diplomas in jeopardy

Ai-generated writing is almost impossible to detect and tensions erupting at a texas university expose the difficulties facing educators.

Students at Texas A&M University at Commerce were in celebration mode this past weekend, as parents filed into the university’s Field House to watch students donned in cap and gown walk the graduation stage.

But for pupils in Jared Mumm’s animal science class, the fun was cut short when they received a heated email Monday afternoon saying that students were in danger of failing the class for using ChatGPT to cheat. “The final grade for the course is due today at 5 p.m.,” the instructor warned, according to a copy of the note obtained by The Washington Post. “I will be giving everyone in this course an ‘X,'” indicating incomplete.

Mumm, an instructor at the university’s agricultural college, said he’d copied the student essays into ChatGPT and asked the software to detect if the artificial intelligence-backed chatbot had written the assignments. Students flagged as cheating “received a 0."

He accompanied the email with personal notes in an online portal hosting grades. “I will not grade chat Gpt s***,” he wrote on one student’s assignment, according to a screenshot obtained by The Post. “I have to gauge what you are learning not a computer.”

Students and teachers: Tell The Post how you use ChatGPT and other AI tools

The email caused a panic in the class, with some students fearful their diplomas were at risk. One senior, who had graduated over the weekend, said the accusation sent her into a frenzy. She gathered evidence to prove her innocence — she’d written her essays in Google Docs, which records timestamps — and presented it to Mumm at a meeting.

The student, who spoke to The Post under the condition of anonymity to discuss matters without fear of academic retribution, said she felt betrayed.

“We’ve been through a lot to get these degrees,” she said in an interview with The Post. “The thought of my hard work not being acknowledged, and my character being questioned. … It just really frustrated me.” (Mumm did not return a request for comment.)

Teachers are on alert for inevitable cheating after release of ChatGPT

The rise of generative artificial intelligence , which underlies software that creates words, texts and images, is sparking a pivotal moment in education. Chatbots can craft essays, poems, computer code and songs that can seem human-made, making it difficult to ascertain who is behind any piece of content.

While ChatGPT cannot be used to detect AI-generated writing, a rush of technology companies are selling software they claim can analyze essays to detect such text. But accurate detection is very difficult, according to educational technology experts, forcing American educators into a pickle : adapt to the technology or make futile attempts to limit the ways it’s used.

The responses range the gamut. The New York City Department of Education has banned ChatGPT in its schools, as has the University of Sciences Po, in Paris , citing concerns it may foster rampant plagiarism and undermine learning. Other professors openly encourage use of chatbots, comparing them to educational tools like a calculator, and argue teachers should adapt curriculums to the software.

Yet educational experts say the tensions erupting at Texas A&M lay bare a troubling reality: protocols on how and when to use chatbots in classwork are vague and unenforceable, with any effort to regulate use risking false accusations.

“Do you want to go to war with your students over AI tools?” said Ian Linkletter, who serves as emerging technology and open-education librarian at the British Columbia Institute of Technology. “Or do you want to give them clear guidance on what is and isn’t okay, and teach them how to use the tools in an ethical manner?”

Michael Johnson, a spokesman for Texas A&M University at Commerce, said in a statement that no students failed Mumm’s class or were barred from graduating. He added that “several students have been exonerated and their grades have been issued, while one student has come forward admitting his use of [ChatGPT] in the course.”

He added that university officials are “developing policies to address the use or misuse of AI technology in the classroom.”

A curious person’s guide to artificial intelligence

In response to concerns in the classroom, a fleet of companies have released products claiming they can flag AI generated text. Plagiarism detection company Turnitin unveiled an AI-writing detector in April to subscribers. A Post examination showed it can wrongly flag human generated text as written by AI. In January, ChatGPT-maker OpenAI said it created a tool that can distinguish between human and AI-generated text, but noted that it “is not fully reliable” and incorrectly labels such text 9 percent of the time.

Detecting AI generated text is hard. The software searches lines of text and looks for sentences that are “too consistently average,” Eric Wang, Turnitin’s vice president of AI, told The Post in April.

Educational technology experts said use of this software may harm students — particularly nonnative English speakers or basic writers, whose writing style may more closely match what an AI generated tool might generate. Chatbots are trained on troves of text, working like an advanced version of auto-complete to predict the next word in a sentence — a practice often resulting in writing that is by definition eerily average.

But as ChatGPT use spreads, it’s imperative that teachers begin to tackle the problem of false positives, said Linkletter.

He says AI detection will have a hard time keeping pace with the advances in large language models. For instance, Turnitin.com can flag AI text written by GPT-3.5, but not its successor model, GPT-4, he said. “Error detection is not a problem that can be solved,” Linkletter added. “It’s a challenge that will only grow increasingly more difficult.”

But he noted that even if detection software gets better at detecting AI generated text, it still causes mental and emotional strain when a student is wrongly accused. “False positives carry real harm,” he said. “At the scale of a course, or at the scale of the university, even a one or 2% rate of false positives will negatively impact dozens or hundreds of innocent students.”

We tested a new ChatGPT-detector for teachers. It flagged an innocent student.

At Texas A&M, there is still confusion. Mumm offered students to a chance to submit a new assignment by 5 p.m. Friday to not receive an incomplete for the class. “Several” students chose to do that, Johnson said, noting that their diplomas “are on hold until the assignment is complete.”

Bruce Schneier, a public interest technologist and lecturer at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, said any attempts to crackdown on the use of AI chatbots in classrooms is misguided, and history proves that educators must adapt to technology. Schneier doesn’t discourage the use of ChatGPT in his own classrooms.

“There are lots of years when the pocket calculator was used for all math ever, and you walked into a classroom and you weren’t allowed to use it,” he said. “It took probably a generational switch for us to realize that’s unrealistic.”

Educators must grapple with the concept of “what does it mean to test knowledge.” In this new age, he said, it will be hard to get students to stop using AI to write first drafts of essays, and professors must tailor curriculums in favor of other assignments, such as projects or interactive work.

“Pedagogy is going to be different,” he said. “And fighting [AI], I think it’s a losing battle.”

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

'Everybody is cheating': Why this teacher has adopted an open ChatGPT policy

Mary Louise Kelly

Not all educators are shying away from artificial intelligence in the classroom. Jeff Pachoud/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Not all educators are shying away from artificial intelligence in the classroom.

Ethan Mollick has a message for the humans and the machines: can't we all just get along?

After all, we are now officially in an A.I. world and we're going to have to share it, reasons the associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania's prestigious Wharton School.

"This was a sudden change, right? There is a lot of good stuff that we are going to have to do differently, but I think we could solve the problems of how we teach people to write in a world with ChatGPT," Mollick told NPR.

Ever since the chatbot ChatGPT launched in November, educators have raised concerns it could facilitate cheating.

Some school districts have banned access to the bot, and not without reason. The artificial intelligence tool from the company OpenAI can compose poetry. It can write computer code. It can maybe even pass an MBA exam.

One Wharton professor recently fed the chatbot the final exam questions for a core MBA course and found that, despite some surprising math errors, he would have given it a B or a B-minus in the class .

A new AI chatbot might do your homework for you. But it's still not an A+ student

And yet, not all educators are shying away from the bot.

This year, Mollick is not only allowing his students to use ChatGPT, they are required to. And he has formally adopted an A.I. policy into his syllabus for the first time.

He teaches classes in entrepreneurship and innovation, and said the early indications were the move was going great.

"The truth is, I probably couldn't have stopped them even if I didn't require it," Mollick said.

This week he ran a session where students were asked to come up with ideas for their class project. Almost everyone had ChatGPT running and were asking it to generate projects, and then they interrogated the bot's ideas with further prompts.

"And the ideas so far are great, partially as a result of that set of interactions," Mollick said.

Users experimenting with the chatbot are warned before testing the tool that ChatGPT "may occasionally generate incorrect or misleading information." OpenAI/Screenshot by NPR hide caption

He readily admits he alternates between enthusiasm and anxiety about how artificial intelligence can change assessments in the classroom, but he believes educators need to move with the times.

"We taught people how to do math in a world with calculators," he said. Now the challenge is for educators to teach students how the world has changed again, and how they can adapt to that.

Mollick's new policy states that using A.I. is an "emerging skill"; that it can be wrong and students should check its results against other sources; and that they will be responsible for any errors or omissions provided by the tool.

And, perhaps most importantly, students need to acknowledge when and how they have used it.

"Failure to do so is in violation of academic honesty policies," the policy reads.

Planet Money

This 22-year-old is trying to save us from chatgpt before it changes writing forever.

Mollick isn't the first to try to put guardrails in place for a post-ChatGPT world.

Earlier this month, 22-year-old Princeton student Edward Tian created an app to detect if something had been written by a machine . Named GPTZero, it was so popular that when he launched it, the app crashed from overuse.

"Humans deserve to know when something is written by a human or written by a machine," Tian told NPR of his motivation.

Mollick agrees, but isn't convinced that educators can ever truly stop cheating.

He cites a survey of Stanford students that found many had already used ChatGPT in their final exams, and he points to estimates that thousands of people in places like Kenya are writing essays on behalf of students abroad .

"I think everybody is cheating ... I mean, it's happening. So what I'm asking students to do is just be honest with me," he said. "Tell me what they use ChatGPT for, tell me what they used as prompts to get it to do what they want, and that's all I'm asking from them. We're in a world where this is happening, but now it's just going to be at an even grander scale."

"I don't think human nature changes as a result of ChatGPT. I think capability did."

The radio interview with Ethan Mollick was produced by Gabe O'Connor and edited by Christopher Intagliata.

ChatGPT Cheating: What to Do When It Happens

- Share article

The latest version of ChatGPT has only been around for a few months. But Aaron Romoslawski, the assistant principal at a Michigan high school, has already seen a handful of students trying to pass off writing produced by the artificial-intelligence-powered tool as their own work.

The signs are almost always obvious, Romoslawski said. Typically, a student will have been turning in work of a certain quality throughout the year, and then “suddenly, we’re seeing these much higher quality assignments pop up out of nowhere,” he said.

Romoslawski and his colleagues don’t start with a punitive response, however. “We see it as an opportunity to have a conversation.”

Those “don’t let the robot do your homework” talks are becoming all too common in schools these days. More than a quarter of K-12 teachers have caught their students cheating using ChatGPT , according to a recent survey by study.com, an online learning platform.

What’s the best way for educators to handle this high-tech form of plagiarism? Here are six tips drawn from educators and experts, including a handy guide created by CommonLit and Quill , two education technology nonprofits focused on building students’ literacy skills.

1. Make your expectations very clear

Students need to know what exactly constitutes cheating, whether AI tools are involved or not.

“Every school or district needs to put stakes in the ground [on a] policy around academic dishonesty, and what that means specifically,” said Michelle Brown, the founder and CEO of CommonLit. Schools can decide how much or how little students can rely on AI to make cosmetic changes or do research, she said, and should make that clear to students. She recommended “the heart of the policy [be] about allowing students to do intellectually rigorous work.”

2. Talk to students about AI in general and ChatGPT in particular

If it appears a student may have passed off ChatGPT’s work as their own, sit down with them one on one, CommonLit and Quill recommend. Then talk about the tool and AI in general. Questions could include: Have you heard of ChatGPT? What are other students saying about it? What do you think it should be used for? Discuss the promises—and potential pitfalls—of artificial intelligence.

“One of the big concerns right now is that teachers want to encourage curiosity about AI,” said Peter Gault, Quill’s founder and executive director. Strict discipline at this point “doesn’t sit right with teachers where there’s a lot of natural curiosity here.”

Romoslawski uses that approach. And so far, he hasn’t had a student try to use ChatGPT on an assignment twice. “We’ve gotten to the point where it’s a conversation and students are redoing the assignment in their own words,” he said.

3. If students use ChatGPT for an assignment, they must attribute what material they used from it

If students are allowed to use ChatGPT or another AI tool for research or other help, let them know how and why they should credit that information, Brown said. Since users can’t link back to a ChatGPT response, she suggested students share the prompt they used to generate the information in their citation.

When Romoslawski and his colleagues suspect a student used ChatGPT to complete an assignment when they weren’t supposed to, he also brings up citation, in part as a way into the conversation.

“We ask the students ‘did you use any resources that you don’t cite?’” he said. “And often, the student says ‘yes.’ And so, then it creates a conversation about how to properly cite and attribute and why we do that.”

4. Ask students directly if they used ChatGPT

Don’t beat around the bush if you suspect a student may have used AI to cheat. Ask them in a very straightforward way if they did, CommonLit and Quill say.

If students say “yes,” Romoslawski likes to get a sense of why. “More often than not, the student was just struggling on the assignment. They had a roadblock. They didn’t know what to do,” he said. “They were crunched for time, because we’re a high-achieving high school and our students are taking some pretty rigorous courses. This was their third homework assignment of the night and they just wanted to get through it.”

If the student says “no,” but you still suspect them of cheating, ask if they got other help with the assignment. If they still say “no,” explain your concerns by pointing out differences between the work they turned in and their previous writing, CommonLit and Quill suggest.

5. Don’t rely on ChatGPT detectors alone to determine if there was cheating

There are a number of tools—including one from OpenAI, ChatGPT’s developer—that purport to be able to distinguish an AI-crafted story or essay from one written by a human . But most of these detectors don’t publish their accuracy rates. And those that do are ineffective about 10 to 20 percent of the time.

“You can’t fully rely on that as the sole proof of academic dishonesty,” Brown said.

6. Make it clear why learning to write on your own is important

Students in general, and particularly students who take advantage of AI to cheat, need to understand what they are missing out on when they take a technology-enabled shortcut. Educators should try to persuade students that learning to write on their own will help them reason and think, or be critical to future job success, Gault said.

But others will need a more immediate incentive. The strongest argument one teacher came up with, according to Quill’s Gault? Tell students that learning to write will make them more persuasive, and therefore, “you can convince your parents to do what you want.”

A version of this article appeared in the March 08, 2023 edition of Education Week as ChatGPT Cheating: What to Do When It Happens

Sign Up for EdWeek Tech Leader

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Have a language expert improve your writing

Check your paper for plagiarism in 10 minutes, generate your apa citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Using AI tools

Is Using ChatGPT Cheating?

Published on June 29, 2023 by Eoghan Ryan . Revised on September 14, 2023.

Using ChatGPT and other AI tools to cheat is academically dishonest and can have severe consequences.

However, using these tools is not always academically dishonest . It’s important to understand how to use these tools correctly and ethically to complement your research and writing skills. You can learn more about how to use AI tools responsibly on our AI writing resources page.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

How can chatgpt be used to cheat, what are the risks of using chatgpt to cheat, how to use chatgpt without cheating, frequently asked questions.

ChatGPT and other AI tools can be used to cheat in various ways. This can be intentional or unintentional and can vary in severity. Some examples of the ways in which ChatGPT can be used to cheat include:

- AI-assisted plagiarism: Passing off AI-generated text as your own work (e.g., essays, homework assignments, take-home exams)

- Plagiarism : Having the tool rephrase content from another source and passing it off as your own work

- Self-plagiarism : Having the tool rewrite a paper you previously submitted with the intention of resubmitting it

- Data fabrication: Using ChatGPT to generate false data and presenting them as genuine findings to support your research

Using ChatGPT in these ways is academically dishonest and very likely to be prohibited by your university. Even if your guidelines don’t explicitly mention ChatGPT, actions like data fabrication are academically dishonest regardless of what tools are used.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

ChatGPT does not solve all academic writing problems and using ChatGPT to cheat can have various negative impacts on yourself and others. ChatGPT cheating:

- Leads to gaps in your knowledge

- Is unfair to other students who did not cheat

- Potentially damages your reputation

- May result in the publication of inaccurate or false information

- May lead to dangerous situations if it allows you to avoid learning the fundamentals in some contexts (e.g., medicine)

When used correctly, ChatGPT and other AI tools can be helpful resources that complement your academic writing and research skills. Below are some tips to help you use ChatGPT ethically.

Follow university guidelines

Guidelines on how ChatGPT may be used vary across universities. It’s crucial to follow your institution’s policies regarding AI writing tools and to stay up to date with any changes. Always ask your instructor if you’re unsure what is allowed in your case.

Use the tool as a source of inspiration

If allowed by your institute, use ChatGPT outputs as a source of guidance or inspiration, rather than as a substitute for coursework. For example, you can use ChatGPT to write a research paper outline or to provide feedback on your text.

You can also use ChatGPT to paraphrase or summarize text to express your ideas more clearly and to condense complex information. Alternatively, you can use Scribbr’s free paraphrasing tool or Scribbr’s free text summarizer , which are designed specifically for these purposes.

Practice information literacy skills

Information literacy skills can help you use AI tools more effectively. For example, they can help you to understand what constitutes plagiarism, critically evaluate AI-generated outputs, and make informed judgments more generally.

You should also familiarize yourself with the user guidelines for any AI tools you use and get to know their intended uses and limitations .

Be transparent about how you use the tools

If you use ChatGPT as a primary source or to help with your research or writing process, you may be required to cite it or acknowledge its contribution in some way (e.g., by providing a link to the ChatGPT conversation). Check your institution’s guidelines or ask your professor for guidance.

Using ChatGPT in the following ways is generally considered academically dishonest:

- Passing off AI-generated content as your own work

- Having the tool rephrase plagiarized content and passing it off as your own work

- Using ChatGPT to generate false data and presenting them as genuine findings to support your research

Using ChatGPT to cheat can have serious academic consequences . It’s important that students learn how to use AI tools effectively and ethically.

Using ChatGPT to cheat is a serious offense and may have severe consequences.

However, when used correctly, ChatGPT can be a helpful resource that complements your academic writing and research skills. Some tips to use ChatGPT ethically include:

- Following your institution’s guidelines

- Understanding what constitutes plagiarism

- Being transparent about how you use the tool

No, it’s not a good idea to do so in general—first, because it’s normally considered plagiarism or academic dishonesty to represent someone else’s work as your own (even if that “someone” is an AI language model). Even if you cite ChatGPT , you’ll still be penalized unless this is specifically allowed by your university . Institutions may use AI detectors to enforce these rules.

Second, ChatGPT can recombine existing texts, but it cannot really generate new knowledge. And it lacks specialist knowledge of academic topics. Therefore, it is not possible to obtain original research results, and the text produced may contain factual errors.

However, you can usually still use ChatGPT for assignments in other ways, as a source of inspiration and feedback.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Ryan, E. (2023, September 14). Is Using ChatGPT Cheating?. Scribbr. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/ai-tools/chatgpt-cheating/

Is this article helpful?

Eoghan Ryan

Other students also liked, how to write an essay with chatgpt | tips & examples, how to use chatgpt in your studies, what are the limitations of chatgpt.

Eoghan Ryan (Scribbr Team)

Thanks for reading! Hope you found this article helpful. If anything is still unclear, or if you didn’t find what you were looking for here, leave a comment and we’ll see if we can help.

Still have questions?

"i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Editor's Pick

ChatGPT, Cheating, and the Future of Education

In the depths of fall term finals, having completed a series of arduous exams, one student was exhausted. The only thing between her and winter break was a timed exam for a General Education class that she was taking pass-fail. Drained, anxious and feeling “like a deflated balloon,” she started the clock. The exam consisted of two short essays. By the time she finished the first one, she had nothing left to give. To pass the class, all she needed was to turn in something for the second essay. She had an idea.

Before finals started, her friends had told her about ChatGPT, OpenAI’s free new chatbot which uses machine learning to respond to prompts in fluent natural language and code. She had yet to try it for herself. With low expectations, she made an account on OpenAI’s website and typed in the prompt for her essay. The quality of the results pleasantly surprised her. With some revision, she turned ChatGPT’s sentences into her essay. Feeling guilty but relieved, she submitted it: Finally, she was done with the semester.

This student and others in this article were granted anonymity by The Crimson to discuss potential violations of Harvard’s Honor Code and other policies out of concerns for disciplinary action.

Since its Nov. 30, 2022 release, ChatGPT has provoked awe and fear among its millions of users. Yet its seeming brilliance distracts from important flaws: It can produce harmful content and often writes fiction as if it were fact.

Because of these limitations and the potential for cheating, many teachers are worried about ChatGPT’s impact on the classroom. Already, the application has been banned by school districts across the country, including those of New York City, Seattle, and Los Angeles.

These fears are not unfounded. At Harvard, ChatGPT quickly found its way onto students’ browsers. In the midst of finals week, we encountered someone whose computer screen was split between two windows: on the left, an open-internet exam for a statistics class, and on the right, ChatGPT outputting answers to his questions. He admitted that he was also bouncing ideas for a philosophy paper off the AI. Another anonymous source we talked to used the chatbot to complete his open-internet Life Sciences exam.

But at the end of the fall term, Harvard had no official policy prohibiting the use of ChatGPT. Dean of the College Rakesh Khurana, in a December interview with The Crimson, did not view ChatGPT as representing a new threat to education: “There have always been shortcuts,” he said. “We leave decisions around pedagogy and assignments and evaluation up to the faculty.”

On Jan. 20, Acting Dean of Undergraduate Education Anne Harrington sent an email to Harvard educators acknowledging that ChatGPT’s abilities have “raised questions for all of us.”

In her message, Harrington relayed guidance from the Office of Undergraduate Education. At first glance, the language seemed to broadly prohibit the use of AI tools for classwork, warning students that Harvard’s Honor Code “forbids students to represent work as their own that they did not write, code, or create,” and that “Submission of computer-generated text without attribution is also prohibited by ChatGPT’s own terms of service.”

But, the email also specified that instructors could “use or adapt” the guidance as they saw fit, allowing them substantial flexibility. The guidance did not clarify how to view the work of students who acknowledge their use of ChatGPT. Nor did it mention whether students can enlist ChatGPT to give them feedback or otherwise supplement their learning.

Some students are already making the most of this gray area. One student we talked to says that he uses ChatGPT to explain difficult mathematical concepts, adding that ChatGPT explains them better than his teaching fellow.

Natalia I. Pazos ’24 uses the chatbot as a kind of interactive SparkNotes. After looking through the introduction and conclusion of a dense Gen Ed reading herself, she asks ChatGPT to give her a summary. “I don’t really have to read the full article, and I feel like it gives me sometimes a better overview,” she says.

Professors are already grappling with whether to ban ChatGPT or let students use it. But beyond this semester, larger questions loom. Will AI simply become another tool in every cheater’s arsenal, or will it radically change what it means to learn?

‘Don’t Rely on Me, That’s a Crime’

Put yourself in our place: It’s one of those busy Saturdays where you have too much to do and too little time to do it, and you set about writing a short essay for History 1610: “East Asian Environments.” The task is to write about the impact of the 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and subsequent nuclear meltdown in Japan. In a database, you encounter an image of a frozen clock in a destroyed school. Two precious hours pass as you research the school, learning about the ill-prepared evacuation plans and administrative failures that led to 74 children’s deaths. As you type up a draft, your fingers feel tense. It’s a harrowing image — you can’t stop envisioning this clock ticking down the moments until disaster. After spending six hours reading and writing, you finally turn the piece in.

But what if the assignment didn’t have to take so much time? We tried using ChatGPT to write this class essay (which, to be clear, was already turned in). After a minute or two refining our prompts, we ended up with a full essay, which began with:

Ticking away the moments of a typical school day, the clock on the wall of Okawa Elementary School suddenly froze on March 11, 2011, as the world around it was shattered by a massive earthquake and tsunami. The clock, once a symbol of the passage of time, now stood as a haunting reminder of the tragedy that had struck the school.

In less than five minutes, ChatGPT did what originally took six hours. And it did it well enough.

Condensing hours into minutes is no small feat, and an enticing prospect for many. Students have many different demands on their time, and not everyone puts academics first. Some pour their time into intense extracurriculars, pre-professional goals, or jobs. (People also want to party.)

Yet the principle underlying a liberal arts curriculum — one that’s enshrined in Harvard’s mission — is the value of intellectual transformation. Transforming yourself is necessarily difficult. Learning the principles of quantum mechanics or understanding what societies looked like before the Industrial Revolution requires deconstructing your worldview and building it anew. Harvard’s honor code, then, represents not just a moral standard but also an expectation that students go through that arduous process.

That’s the theory. In practice, many students feel they don’t always have the time to do the difficult work of intellectual transformation. But they still care about their grades, so they cut corners. And now, just a few clicks away, there’s ChatGPT: a tool so interactive it practically feels like it’s your own work.

So, can professors stop students from using ChatGPT? And should they?

This semester, many instructors at Harvard prohibited students from using ChatGPT, treating it like any other form of academic dishonesty. Explicit bans on ChatGPT became widespread, greeting students on syllabi for classes across departments, from Philosophy to Neuroscience.

Some instructors, like professor Catherine A. Brekus ’85, who teaches Religion 120: “Religion and Nationalism in the United States: A History,” directly imported the Office of Undergraduate Education’s suggested guidance onto their syllabus. Others, like Spanish 11, simply told students not to use it in an introductory lecture. The syllabus for Physical Sciences 12a went so far as to discourage use of the tool with multiple verses of a song written by ChatGPT:

I’m just a tool, a way to find some answers

But I can’t do the work for you, I’m not a dancer

You gotta put in the effort, put in the time

Don’t rely on me, that’s a crime

Making these professors’ lives difficult is that, at the moment, there is no reliable way to detect whether a student’s work is AI-generated. In late January, OpenAI released a classifier to distinguish between AI and human-written text, but it only correctly identified AI-written text 26 percent of the time . GPTZero, a classifier launched in January by Princeton undergraduate Edward Tian, now claims to correctly identify human-written documents 99 percent of the time and AI-written documents 85 percent of the time.

Still, a high likelihood of AI involvement in an assignment may not be enough evidence to bring a student before the Honor Council. Out of more than a dozen professors we’ve spoken with, none currently plan to use an AI detector.

Not all instructors plan to ban ChatGPT at all. Incoming assistant professor of Computer Science Jonathan Frankle questions whether students in advanced computer science classes should be forced to use older, more time-consuming tools if they’ve already mastered the basics of coding.

“It would be a little bit weird if we said, you know, in CS 50, go use punch cards, you’re not allowed to use any modern tools,” he says, referring to the tool used by early computer scientists to write programs.

Harvard Medical School professor Gabriel Kreiman feels similarly. In his courses, students are welcome to use ChatGPT, whether for writing their code or their final reports. His only stipulation is that students inform him when they’ve used the application and understand that they’re still responsible for the work. “If it’s wrong,” he says, “you get the grade, not ChatGPT.”

Kumaresh Krishnan, a teaching fellow for Gen Ed 1125: “Artificial & Natural Intelligence,” believes that if the class isn’t focused on how to code or write, then ChatGPT use is justified under most circumstances. Though he is not responsible for the academic integrity policy of the course, Krishnan believes that producing a nuanced, articulate answer with ChatGPT requires students to understand key concepts.

“If you’re using ChatGPT that well, maybe you don’t understand all the math behind it, maybe you don’t understand all the specifics — but you're understanding the game enough to manipulate it,” he says. “And that itself, that’s a win.”

The student that used ChatGPT for an open-internet life sciences exam last semester says he had mastered the concepts but just couldn’t write fast enough. ChatGPT, he says, only “fleshed out” his answers. He received one of the highest grades in the class.

While most of the teachers we spoke with prohibit the use of ChatGPT, not everyone has ruled out using it in the future. Harvard College Fellow William J. Stewart, in his course German 192: “Artificial Intelligences: Body, Art, and Technology in Modern Germany,” explicitly forbids the use of ChatGPT. But for him, the jury is still out on ChatGPT’s pedagogical value: “Do I think it has a place in the classroom? Maybe?”

‘A Pedagogical Challenge’

“There are two aspects that we need to think about,” says Soroush Saghafian when asked about ChatGPT. “One is that, can we ban it? Second, should we ban it?” To Saghafian, an associate professor of public policy at the Kennedy School who is teaching a course on machine learning and big data analytics, the answer to both questions is no. In his view, people will always find ways around prohibitive measures. “It’s like trying to ban use of the internet,” he says.

Most educators at Harvard who we spoke with don’t share the sense of panic that permeates the headlines. Operating under the same assumption as Saghafian — that it is impossible to prevent students from using ChatGPT — educators have adopted diverse strategies to adapt their curricula.

In some language classes, for example, threats posed by intelligent technology are nothing new. “Ever since the internet, really, there have been increasingly large numbers of things that students can use to do their work for them,” says Amanda Gann, an instructor for French 50: “Advanced French II: Justice, Equity, Rights, and Language.”

Even before the rise of large language models like ChatGPT, French 50 used measures to limit students’ ability to use tools like Google Translate for assignments. “The first drafts of all of their major assessments are done in class,” Gann says.

Still, Gann and the other instructors made additional changes this semester in response to the release of ChatGPT. After writing first drafts in class, French 50 students last semester revised their papers at home. This spring, students will instead transform their draft composition into a conversational video. To ensure that students don’t write their remarks beforehand — or have ChatGPT write them — the assignment will be graded on how “spontaneous and like fluid conversation” their speech is.

Instructors were already considering an increased emphasis on oral assessments, Gann says, but she might not have implemented it without the pressure of ChatGPT.

Gann welcomes the change. She views emergence of large language models like ChatGPT as a “pedagogical challenge.” This applies both to making her assignments less susceptible to AI — “Is this something only a human could do?” — as well as reducing the incentive to use AI in the first place. In stark contrast to the projected panic about ChatGPT, Gann thinks the questions it has posed to her as an educator “make it kind of fun.”

Stewart thinks that ChatGPT will provide “a moment to reflect from the educator’s side.” If ChatGPT can do their assignments, perhaps their assignments are “uninspired, or they’re kind of boring, or they’re asking students to be repetitive,” he says.

Stewart also trusts that his students see the value in learning without cutting corners. In his view, very few of the students in his high-level German translation class would “think that it’s a good use of their time to take that class and then turn to the translating tool,” he says. “The reason they’re taking that class is because they also understand that there’s a way to get a similar toolbox in their own brain.” To Stewart, students must see that developing that toolbox for themselves is “far more powerful and far more useful” than copying text into Google Translate.

Computer Science professor Boaz Barak shares Stewart’s sentiment: “Generally, I trust students. I personally don't go super out of my way to try to detect student cheating,” he says. “And I am not going to start.”

Frankle, too, won’t be going out of his way to detect whether his students are cheating — instead, he assumes that students in his CS classes will be using tools like ChatGPT. Accordingly, he intends to make his assignments and exams significantly more demanding. In previous courses, Frankle says he might have asked students to code a simple neural network. With the arrival of language models that can code, he’ll ask that his students reproduce a much more complex version inspired by cutting-edge research. “Now you can get more accomplished, so I can ask more of you,” he says.

Other courses may soon follow suit. Just last week, the instructor for CS 181: “Machine Learning,” offered students extra credit if they used ChatGPT as an “educational aid” to support them in actions like debugging code.

Educators across disciplines are encouraging students to critically engage with ChatGPT in their classes.

Harvard College Fellow Maria Dikcis, who teaches English 195BD: “The Dark Side of Big Data,” assigned students a threefold exercise — first write a short analytical essay, then ask ChatGPT to produce a paper on the same topic, and finally compare their work and ChatGPT’s. “I sort of envisioned it as a human versus machine intelligence,” she says. She hopes the assignment will force students to reflect on the seeming brilliance of the model but also to ask, in her words, “What are its shortcomings, and why is that important?”

Saghafian also thinks it is imperative that students interact with this technology, both to understand its uses as well as to see its “cracks.” In the 2000s, teachers helped students learn the benefits and pitfalls of internet resources like Google search. Saghafian recommends that educators use a similar approach with ChatGPT.

And these cracks can be easy to miss. When she first started using ChatGPT to summarize her readings, Pazos recalls feeling “really impressed by how fast it happened.” To her, because ChatGPT displays its responses word by word, “it feels like it’s thinking.”

“One of the hypes about this technology is that people think, oh, it can do everything, it can think, it can reason,” Saghafian says. Through critical engagement with ChatGPT, students can learn that “none of those is correct.” Large language models, he explains, “don't have the ability to think.” Their writing process, in fact, can show students the difference between reasoning and outputting language.

A Troublesome Model

In the Okawa elementary school essay written by ChatGPT, one of the later paragraphs stated: The surviving students and teachers were quickly evacuated to safety.

In fact, the students and teachers were not evacuated to safety. They were evacuated toward the tsunami — which was exactly why Okawa Elementary School became such a tragedy. ChatGPT could describe the tragedy, but since it did not understand what made it a tragedy, it spat out a fundamental falsehood with confidence.

This behavior is not out of the ordinary. ChatGPT consistently makes factual errors, even though OpenAI designed it not to and has repeatedly updated it. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Despite impressive capabilities, ChatGPT and other large language models come with fundamental limitations and potential for harm.

Many of these flaws are baked into the way ChatGPT works. ChatGPT is an example of what researchers call a large language model. LLMs work primarily by processing huge amounts of data. This is called training, and in ChatGPT’s case, the training likely involved processing most of the text on the internet — an ocean of niche Wikipedia articles, angry YouTube comment threads, poorly written Harry Potter fan fiction, recipes for lemon poppy seed muffins, and everything in between.

Through that ocean of training data, LLMs become adept at recognizing and reproducing the complex statistical relationships between words in natural language. For ChatGPT, this might mean learning what types of words appear in a Wikipedia article as opposed to a chapter of fanfiction, or what lists of ingredients are most likely to follow the title “pistachio muffins.” So, when ChatGPT is given a prompt, like “how do I bake pistachio muffins,” it uses the statistical relationships it has learned to predict the most likely response to that prompt.

Occasionally, this means regurgitating material from its training set (like copying a muffin recipe) or adapting a specific source to the prompt (like summarizing a Wikipedia article). But more often, ChatGPT synthesizes its responses from the correlations it has learned between words. This synthesis is what gives it the uncanny yet hilarious ability to write the opening of George Orwell’s “Nineteen Eighty-Four” in the style of a SpongeBob episode, or explain the code for a Python program in the voice of a wiseguy from a 1940s gangster movie.

This explains the propensity of LLMs to produce false claims even when asked about real events. The algorithms behind ChatGPT have no conception of truth — only of correlations between words. Moreover, the distinction between truth and falsehood on the written internet is rarely clear from the words alone.

Take the Okawa Elementary School example. If you read a blog post about the effects of a disastrous earthquake on an elementary school, how would you determine whether it was true? You might consider the plausibility of the story, the reputability of the writer, or whether corroborating evidence, like photographs or external links, were available. Your decision, in other words, would not depend solely on the text of the post. Instead, it would be informed by digital literacy, fact-checking, and your knowledge of the outside world. Language models have none of that.

The difference between fact and fiction is not the only elementary concept left out of ChatGPT’s algorithm. Despite its ability to predict and reproduce complex patterns of writing, ChatGPT often cannot parse comparatively simple logic. The technology will output confident-sounding incorrect answers when asked to solve short word problems, add two large numbers, or write a sentence ending with the letter “c.” Questioning its answer to a math problem may lead it to admit a mistake, even if there wasn’t one. Given the list of words: “ChatGPT” “has” “endless” “limitations,” it told us that the third-to-last-word on that list was: “ChatGPT.” (Narcissistic much?)

When James C. Glaser ’25 asked ChatGPT to compose a sestina — a poetic form with six-line stanzas and other constraints — the program outputted stanzas with four lines, no matter how explicit he made the prompt. At some point during the back-and-forth, he says, “I just sort of gave up and realized that it was kind of ridiculous.”

Lack of sufficient training data in certain areas can also affect ChatGPT’s performance. Multiple faculty members who teach languages other than English told us ChatGPT performed noticeably worse in those languages.

The content of the training data also matters. The abundance of bias and hateful language on the internet filters into the written output of LLMs, as leading AI ethics researchers such as Timnit Gebru have shown . In English language data, “white supremacist and misogynistic, ageist, etc., views are overrepresented,” a 2021 study co-authored by Gebru found, “setting up models trained on these datasets to further amplify biases and harms.”

Indeed, OpenAI’s GPT-3, a predecessor of ChatGPT that powers hundreds of applications today, is quick to output paragraphs with racist, sexist, anti-semitic, or otherwise harmful messages if prompted, as the MIT Technology Review and others have shown.