We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

CHAPTER 22: Normal Labor

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Introduction, mechanisms of labor.

- NORMAL LABOR CHARACTERISTICS

- MANAGEMENT OF NORMAL LABOR

- LABOR MANAGEMENT PROTOCOLS

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

It follows that some process of adaptation or accommodation of suitable portions for the head to the various pelvic planes is necessary to insure the completion of childbirth. This is brought about by certain movement of the presenting part, which belong to what is termed the mechanism of labour.

—J. Whitridge Williams (1903)

Labor is the process that leads to childbirth. It begins with the onset of regular uterine contractions and ends with delivery of the newborn and expulsion of the placenta. Pregnancy and birth are physiological processes, and thus, labor and delivery should be considered normal for most women.

Pelvic Floor Changes

Many adaptive changes are required for pregnancy and for labor and delivery. According to Nygaard (2015) , vaginal delivery is a traumatic event. To assess this in part, Staer-Jensen and colleagues (2015) obtained transperineal sonographic measurements of the pelvic floor muscles at 21 weeks’ and 37 weeks’ gestation, and again at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months postpartum. In 300 nulliparas, they measured bladder neck mobility and the area within the urogenital hiatus during Valsalva. This hiatus is the U-shaped opening in the pelvic floor muscles through which the urethra, vagina, and rectum pass ( Chap. 2 , Perineum ). In this study, the levator hiatus area was significantly larger at 37 weeks’ gestation and at 6 weeks postpartum compared with earlier pregnancy. Then, by 6 months postpartum, the hiatus had improved and narrowed to return to an area comparable to that at 21 weeks’ gestation. However, no further improvement was noted by 12 months postpartum. Of note, hiatal area enlargement was only seen in those who delivered vaginally.

These findings demonstrate antepartum changes in pelvic floor structure that may reflect adaptations needed to permit vaginal delivery ( Nygaard, 2015 ). Additional pelvic floor changes are discussed in Chapter 4 ( Fallopian Tubes ), and the contributions of pregnancy and delivery to later pelvic organ prolapse and incontinence are described in Chapter 30 ( Cesarean Delivery Risks ).

At the onset of labor, the position of the fetus with respect to the birth canal is critical to the route of delivery and thus should be determined in early labor. Important relationships include fetal lie, presentation, attitude, and position.

Fetal lie describes the relationship of the fetal long axis to that of the mother. In more than 99 percent of labors at term, the fetal lie is longitudinal . A transverse lie is less frequent, and predisposing factors include multiparity, placenta previa, hydramnios, and uterine anomalies ( Chap. 23 , Brow Presentation ). Occasionally, the fetal and maternal axes may cross at a 45-degree angle, forming an oblique lie. This is unstable and becomes longitudinal or transverse during labor.

Sign in or create a free Access profile below to access even more exclusive content.

With an Access profile, you can save and manage favorites from your personal dashboard, complete case quizzes, review Q&A, and take these feature on the go with our Access app.

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

Labour and Delivery Care Module: 5. Conducting a Normal Delivery

Study session 5 conducting a normal delivery, introduction.

In the previous study sessions of this Module, you were introduced to the definition, signs, symptoms and stages of labour and the use of the partograph. You also learned about care of the woman in labour. In this session, you will learn how to assist the woman in the second stage of a normal labour and how to deliver the baby. The second stage is the part of labour when the mother pushes the baby out of the uterus and down the vagina, and the baby is born. Second stage begins when the cervix is completely dilated and ends when the baby is delivered.

During the second stage, the mother’s passive control during the long hours of the first stage of labour is replaced by intense physical effort and exertion for a comparatively short period. The mother and her support person require stamina, courage and confidence from the birth attendant. A healthy outcome for the mother and her baby depends upon your competence in providing quality care and the successful partnership between you and the mother.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 5

When you have studied this session you should be able to:

5.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold . (SAQs 5.1, 5.2 and 5.3)

5.2 Describe the signs of second stage labour and explain what is happening to the mother and the baby as it moves down the birth canal. (SAQs 5.1 and 5.2)

5.3 Describe how you would assess if the second stage is progressing normally and identify the warning signs that sufficient progress is not being made. (SAQs 5.1 and 5.2)

5.4 Describe how you would conduct the normal delivery of a healthy baby and give it immediate newborn care. (SAQs 5.3 and 5.4)

5.5 Explain how you would support bonding between mother and newborn after the delivery. (SAQ 5.5)

5.1 Recognising the signs of second stage labour

The only positive sign in diagnosing second stage of labour is full dilatation of the cervix. The only way you can be certain the cervix is dilated all the way is to do a vaginal examination. But remember: repeated vaginal exams can cause infection. It is better not to do a vaginal exam frequently (less than 4 hours interval) unless:

- When you count the fetal heart beat it is outside the normal range (outside 120–160 beats per minute).

- There is a sudden gush of amniotic fluid, which may indicate that there is a risk for cord prolapse or placental abruption.

- You detect signs of second stage of labour beginning before the next scheduled vaginal examination. (See Box 5.1 for signs of second stage.)

With experience, you can usually tell when the mother is ready to push without doing a vaginal exam.

Box 5.1 Signs of second stage

If the mother has two or more of these signs, she is probably in second stage of labour:

- She feels an uncontrollable urge to push (she may say she needs to pass stool)

- She may hold her breath or grunt during contractions

- She starts to sweat

- Her mood changes — she may become sleepy or more focused

- Her external genitals or anus begin to bulge out during contractions

- She feels the baby’s head begin to move into the vagina

- A purple line appears between the mother’s buttocks as they spread apart from the pressure of the baby’s head.

5.1.1 What happens during second stage of labour?

During second stage, when the baby is high in the vagina, you can see the mother’s genitals bulge during contractions. Her anus may open a little. Between contractions, her genitals relax (Figure 5.1).

Each contraction (and each push from the mother) moves the baby further down. Between contractions, the mother’s uterus relaxes and pulls the baby back up a little (but not as far as it was before the contraction).

After a while, you can see a little of the baby’s head coming down the vagina during contractions. The baby moves like an ocean tide: in and out, in and out, but each time closer to birth (Figures 5.2a–d).

When the baby’s head stretches the vaginal opening to about the size of the palm of your hand (Figure 5.3), the head will stay at the opening - even between contractions. This is called crowning . Once the head is born, the rest of the body usually slips out easily with one or two pushes.

5.1.2 How does the baby move through the birth canal?

Figure 5.4 shows the movement of the baby through the birth canal. Babies move this way if they are positioned head-first, with their backs toward their mother’s bellies. But many babies do not face this way. A baby who faces the mother’s front, or who is breech, moves in a different way. Watch each birth closely to see how babies in different positions move.

5.2 Help the mother and baby have a safe birth

Continue to check the mother’s vital signs as you have been doing during the first stage of labour.

5.2.1 Check the baby’s heart beat

The baby’s heartbeat is harder to hear in second stage because the heart is usually lower in the mother’s belly. If you are experienced, you may be able to hear the baby’s heart between contractions. You can hear it best very low in the mother’s belly, near the pubic bone (Figure 5.5). It is OK for the heartbeat to be as slow as 100 beats a minute during a pushing contraction. But it should come right back up to the normal rate as soon as the contraction is over.

What is the normal fetal heatbeat?

Between 120 and 160 beats per minute.

If the baby’s heartbeat does not come back up within 1 minute, or stays slower than 100 beats a minute for more than a few minutes, the baby may be in trouble. Ask the mother to change position (to lie on her side), and check the baby’s heartbeat again. If it is still slow, ask the mother to stop pushing for a few contractions. Make sure she takes deep, long breaths so that the baby will get adequate oxygen.

5.2.2 Support the mother’s pushing

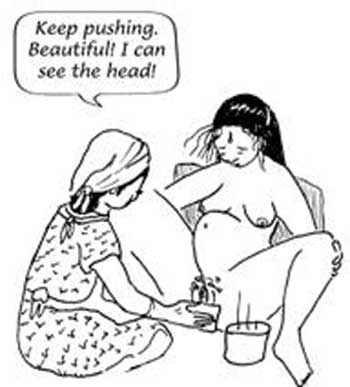

When the cervix is fully dilated, the mother’s body will push the baby out. Some healthcare providers get very excited during the pushing stage. They yell at mothers, ‘Push! Push!’ but mothers do not usually need much help to push. Their bodies push naturally, and when they are encouraged and supported, women will usually find the way to push that feels right and gets the baby out.

If a mother has difficulty pushing, do not scold or threaten her. And never insult or hit a woman to make her push. Upsetting or frightening her can slow the birth. Instead, explain how to push well (Figure 5.6). Each contraction is a new chance. Praise her for trying.

Tell the mother when you see her outer genitals bulge. Explain that this means the baby is coming down. When you see the head, let the mother touch it. This may also help her to push better.

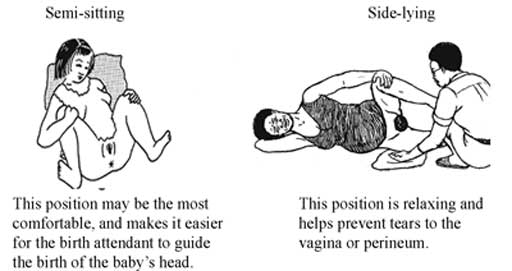

Let the mother choose the position that feels good to her. You already learned about different positions in first stage in Study Session 3. But note that it is not good for the mother to lie flat on her back during a normal birth. Lying flat can squeeze the blood vessels that bring blood to the baby and the mother, and can make the birth slower.

5.2.3 Watch for warning signs

Watch the speed of each birth. If the birth is taking too long, take the woman to a hospital. This is one of the most important things you can do to prevent serious problems or even death of women in labour.

First babies may take a full 2 hours of strong contractions and good pushing to be born. Second and later babies usually take less than 1 hour of pushing. Watch how fast the baby’s head is moving down through the birth canal. As long as the baby continues to move down (even very slowly), and the baby’s heartbeat is normal, and the mother has strength, then the birth is normal and healthy. The mother should continue to push until the head crowns.

But pushing for a long time with no progress can cause serious problems, including fistula, uterine rupture (you will learn about this in Study Session 10 of this Module), or even death of the baby or mother. If you do not see the mother’s genitals bulging after 30 minutes of strong pushing, or if the mild bulging does not increase, the head may not be coming down. If the baby is not moving down at all after 1 hour of pushing, the mother needs help.

Therefore, refer immediately if the woman stayed (couldn’t deliver) in the second stage for more than:

- 1 hour with no good progress (multigravida woman)

- 2 hours with no good progress (primigravida).

5.3 Conducting delivery of the baby

Your skill and judgment are crucial factors in minimising trauma for the mother and ensuring a safe delivery for the baby. These qualities are acquired through experience but certain basic principles must be applied whatever the expertise you have. These are:

- Observation of progress of the labour

- Prevention of infection

- Emotional and physical comfort of the mother

- Anticipation of normal events

- Recognition of abnormal labour or fetal distress.

5.3.1 Prevent tears in the vaginal opening

The birth of the baby’s head may tear the mother’s vaginal opening. But you can prevent tears by supporting the vagina during the birth. In some communities, circumcision of girls (also called female genital cutting) is common. This harmful traditional practice causes scars that may not stretch enough to let the baby out or the scar may tear as the baby is born.

5.3.2 Delivery of the head

Wash your hands well and put on sterile gloves and other protective materials.

Clean the perineal area using antispetic and (if you have them) put clean drapes (cloths) over the mother’s thighs.

Press one hand firmly on the perineum (the skin between the opening of the vagina and the anus). This hand will keep the baby’s chin close to its chest — making it easier for the head to come out (Figure 5.8). Use a piece of cloth or gauze to cover the mother’s anus; some faeces (stool) may be pushed out with the baby’s head.

Use your other hand to apply gentle downward pressure on the top of the baby’s head to keep the baby’s head flexed (bent downwards).

Once the head has crowned, the head is born by the extension of the face, which appears at the perineum.

Clear the baby’s nose and mouth. When the head is born, and before the rest of the body comes out, you may need to help the baby breathe by clearing its mouth and nose. If the baby has some mucus or water in its nose or mouth, wipe it gently with a clean cloth wrapped around your finger.

5.3.3 Check if the cord is around the baby’s neck

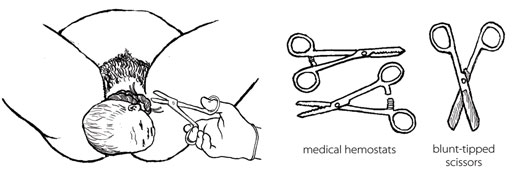

If there is a rest between the birth of the head and the birth of the shoulders, feel for the cord around the baby’s neck.

- If the cord is wrapped loosely around the neck, loosen it so it can slip over the baby’s head or shoulders.

- If the cord is very tight, or if it is wrapped around the neck more than once, try to loosen it and slip it over the head.

- If you cannot loosen the cord, and if the cord is preventing the baby from coming out, you may have to clamp and cut it.

If you can, use medical hemostats (clamps) and blunt-tipped scissors for clamping and cutting the cord in this situation. If you do not have them, use clean string and a new razor. Clamp or tie in two places and cut in between (Figure 5.9). Be very careful not to cut the mother or the baby’s neck.

5.3.4 Delivery of the shoulders

After the baby’s head is born and he or she turns to face the mother’s leg, wait for the next contraction. Ask the mother to give a gentle push as soon as she feels the contraction. Usually, the baby’s shoulders will slip right out. To prevent tearing, try to bring out one shoulder at a time (Figure 5.10).

5.3.5 Delivery of the baby’s body

After the shoulders are born, the rest of the body usually slides out without any trouble. Remember that new babies are wet and slippery. Be careful not to drop the baby!

Put the baby on the mother’s abdomen, dry the baby with a clean cloth and then put a new, clean blanket over him or her to keep the baby warm. Be sure the top of the baby’s head is covered with a hat or blanket. If everything seems OK, give the baby the chance to breastfeed right away. You do not have to wait until the placenta comes out or the cord is cut.

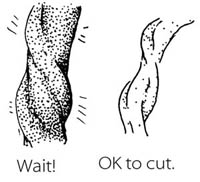

5.3.6 Cutting the cord

Most of the time, there is no need to hurry to cut the cord right away. Leaving the cord attached will help the baby to have enough iron in his or her blood, because some of the blood in the placenta drains along the cord and into the baby. It will also keep the baby on the mother’s belly which is the best place to be right now. Wait until the cord stops pulsing and looks like it is mostly empty of blood.

BUT if the mother is known to be HIV-infected or her HIV status is not known, it is better to cut the cord soon after you have dried the baby and made sure that he or she is warm.

Use a sterile string or sterile clamp to tightly tie or clamp the cord about two finger widths from the baby’s belly. (The baby’s risk of getting tetanus is greater when the cord is cut far from the body.) Tie a square knot (Figure 5.11).

Put another sterile string or clamp one finger from the first knot. And, if you do not have a clamp on the cord on the mother’s side, add a third knot two fingers from the second knot. Putting a double knot on the cord reduces the risk of bleeding.

Cut after the second tie (e.g. the first tie is approximately 3 cm from the baby’s abdomen and the second is approximately 5 cm). Cut after the 5 cm tie with a sterile razor blade or sterile scissors.

5.4 Immediate care of the newborn baby

Essential newborn care includes the following actions. But note that you will learn about resuscitation of the newborn who is not breathing adequately in Study Session 6.

5.4.1 Clean childbirth and cord care

Principles of cleanliness are essential in both home and health post childbirth to prevent infection to the mother and baby. These are:

- Clean your hands

- Clean the mother’s perineum

- Nothing unclean introduced vaginally

- Clean delivery surface

- Cleanliness in cord clamping and cutting.

The stump of the umbilical cord must be kept clean and dry to prevent infection. Wash it with soap and clean water only if it is soiled. Remember:

- Do not apply dressings or substances of any kind

- If the cord bleeds, re-tie it.

It usually falls off 4–7 days after birth, but until this happens, place the cord outside the nappy to prevent contamination with urine/faeces.

5.4.2 Check the newborn

Most babies are alert and strong when they are born. Other babies start slow, but as the first few minutes pass, they breathe and move better, get stronger, and become less blue. Immediately after delivery, clear airways and stimulate the baby while drying. To see how healthy the baby is, watch for:

- Breathing: babies should start to breathe normally within seconds after birth. Babies who cry after birth are usually breathing well. But many babies breathe well and do not cry at all.

- Colour: the baby’s skin should be a normal colour – not pale or bluish.

- Muscle tone: the baby should move his or her arms and legs vigorously.

All of these things should be checked simultaneously within the first minute after birth. You will learn about this in detail in Study Session 6 of this Module.

5.4.3 Warmth and bonding

Newborn babies are at increased risk of getting extremely cold. The mother and the baby should be kept skin-to-skin contact, covered with a clean, dry blanket. This should be done immediately after the birth, even before you cut the cord.

The mother’s body will keep the baby warm, and the smell of the mother’s milk will encourage him or her to suck. Be gentle with a new baby. The first hour is the best time for the mother and baby to be together, and they should not be separated. This time together will also help to start breastfeeding as early as possible.

5.4.4 Early breastfeeding

If everything is normal after the birth, the mother should breastfeed her baby right away (Figure 5.12). She may need some help getting started. The first milk to come from the breast is yellowish and is called colostrum . Some women think that colostrum is bad for the baby and do not breastfeed in the first day after the birth. But colostrum is very important! It is full of protein and helps to protect the baby from infections.

- Breastfeeding makes the uterus contract. This helps the placenta come out, and it may help prevent heavy bleeding.

- Breastfeeding helps the baby to clear fluid from his nose and mouth and breathe more easily.

- Breastfeeding is a good way for the mother and baby to begin to know each other.

- Breastfeeding comforts the baby.

- Breastfeeding can help the mother relax and feel good about her new baby.

If the baby does not seem able to breastfeed, see if it has a lot of mucus in his or her nose. To help the mucus drain, lay the baby across the mother’s chest with its head lower than its body. Stroke the baby’s back from the waist up to the shoulders. After draining the mucus, help the mother to put the baby to the breast again. You will learn a lot more about breastfeeding in the next Module in this curriculum on Postnatal Care .

Summary of Study Session 5

In Study Session 5 you learned that:

- The second stage of labour begins when the cervix is completely dilated and ends when the baby is delivered. Close attention, skilled care and prompt action are needed from you for a safe clean birth.

- The signs of second stage are when the mother feels an uncontrollable urge to push, she holds her breath or grunts during contractions, she starts to sweat, her mood changes, her external genitals or anus begin to bulge out during contractions, she feels the baby’s head begin to move into the vagina, a purple line appears between her buttocks.

- Check the mother’s vital signs, the fetal heart beat and the descent of the baby’s head at intervals to ensure that labour is progressing normally.

- Watch for warning signs that labour is not progressing sufficiently during the second stage and take appropriate action to refer the mother.

- Support the mother’s pushing during the time of actual delivery.

- If the cord is trapped around the baby’s neck, cut it before the body is delivered — but make sure the mother pushes hard to get the baby out fast.

- Maintain cleanliness throughout the entire process of labour and delivery to prevent infection to the mother and baby.

- Keep the newborn baby warm and make sure it is breathing well.

- Initiate early breast feeding.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 5

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering the questions below Case Study 3.1. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 5.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 5.1, 5.2 and 5.3)

Which of the following statements is false ? In each case, explain what is incorrect.

A Full dilatation of the cervix to 10 cm is the most important sign that the second stage of labour is beginning.

B In second stage, the mother’s genitals tend to bulge during contractions and relax between contractions.

C Crowning is the name given to the moment when the baby’s head is completely born.

D In a normal delivery, the baby moves down the birth canal facing the front of the mother’s body, with its back towards her backbone.

E While it is still in the birth canal, the baby’s heartbeat tends to get faster during a contraction.

F Let the mother choose the position that she feels most comfortable in when she gets the urge to push in the second stage of labour.

A is true. Full dilatation of the cervix to 10 cm is the most important sign that second stage of labour is beginning.

B is true. In second stage, the mother’s genitals tend to bulge during contractions and relax between contractions.

C is false. Crowning is when the top of the baby’s head stretches the vaginal opening to the size of your hand and it stays in the opening even between contractions.

D is false. In a normal delivery, the baby moves down the birth canal facing the back of the mother’s body, with its own back towards her belly.

E is false. While it is still in the birth canal, the baby’s heartbeat tends to get slower (not faster) during a contraction.

F is true. You should let the mother choose the position that she feels most comfortable in when she gets the urge to push in the second stage of labour.

SAQ 5.2 (tests Learning Outcome 5.3)

List four warning signs that second stage labour may not be progressing normally.

Warning signs that second stage may not be progressing normally include:

- Fetal heartbeat stays above or below the normal range (120-160 beats per minute) even between contractions of the mother’s uterus.

- A sudden gush of amniotic fluid leaves the vagina, which may indicate a cord prolapse or placental abruption.

- A multigravida mother has been pushing for 1 hour without the baby moving down the birth canal, or a primigravida mother has been pushing for 2 hours with no good progress.

- Baby is not descending and there are signs that it is developing caput or excessive moulding of the fetal skull.

SAQ 5.3 (tests Learning Outcome 5.4)

Imagine that the baby’s head has been born and you are waiting for the next contraction to deliver the baby’s shoulders. What should you do if you find that the umbilical cord is wrapped around the baby’s neck?

First, try to loosen the cord and slip it over the baby’s head. If you cannot loosen it and it is preventing the baby from being delivered, clamp the cord in two places (or tie it with very clean string) and cut it in between the clamps. Be careful not to cut the mother or the baby’s neck.

SAQ 5.4 (tests Learning Outcomes 5.4 and 5.5)

Rearrange the following actions into the correct order during delivery of the baby and immediately afterwards.

A Once the baby’s head is born, help it to breathe by clearing its nose and mouth.

B Wash your hands well and put on sterile gloves and other protective clothing.

C To prevent tearing of the mother’s birth vagina or perineum, deliver the baby’s shoulders one at a time.

D Press one hand firmly over the mother’s perineum.

E When the baby has been completely delivered, put it on the mother’s abdomen and dry it with a clean cloth.

F Clean the mother’s perineal area with antiseptic.

G Clamp or tie the cord in two places and cut it in between the clamps.

H Use your other hand to apply gentle downward pressure on the top of the baby’s head to keep it flexed (bent downwards).

I Cover the baby to keep it warm and give it a chance to breastfeed straight away.

J Use a piece of cloth or gauze to cover the mother’s anus in case any faeces come out with the baby.

K Check that the cord is not around the baby’s neck.

The correct sequence is as follows:

SAQ 5.5 (tests Learning Outcome 5.5)

What do you do to help bonding between the mother and her newborn baby?

To help bonding between the mother and her newborn baby you place the baby on the mother’s abdomen as soon as it is born, and give it an early opportunity to breastfeed. Do not separate the mother and her baby during at least the first hour after the birth.

Except for third party materials and/or otherwise stated (see terms and conditions ) the content in OpenLearn is released for use under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Sharealike 2.0 licence . In short this allows you to use the content throughout the world without payment for non-commercial purposes in accordance with the Creative Commons non commercial sharealike licence. Please read this licence in full along with OpenLearn terms and conditions before making use of the content.

When using the content you must attribute us (The Open University) (the OU) and any identified author in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Licence.

The Acknowledgements section is used to list, amongst other things, third party (Proprietary), licensed content which is not subject to Creative Commons licensing. Proprietary content must be used (retained) intact and in context to the content at all times. The Acknowledgements section is also used to bring to your attention any other Special Restrictions which may apply to the content. For example there may be times when the Creative Commons Non-Commercial Sharealike licence does not apply to any of the content even if owned by us (the OU). In these stances, unless stated otherwise, the content may be used for personal and non-commercial use. We have also identified as Proprietary other material included in the content which is not subject to Creative Commons Licence. These are: OU logos, trading names and may extend to certain photographic and video images and sound recordings and any other material as may be brought to your attention.

Unauthorised use of any of the content may constitute a breach of the terms and conditions and/or intellectual property laws.

We reserve the right to alter, amend or bring to an end any terms and conditions provided here without notice.

All rights falling outside the terms of the Creative Commons licence are retained or controlled by The Open University.

Head of Intellectual Property, The Open University

Labor Progression Case Study (45 min)

Watch More! Unlock the full videos with a FREE trial

Included In This Lesson

Access More! View the full outline and transcript with a FREE trial

A 27-year-old female who is 40 weeks and 2 days pregnant, with contractions occurring once every 10 minutes. The patient is checked in, vital signs are normal, fetal heart tones are normal and the mother and father to-be are settled into their room for the night. It is 4 am and the call light goes off. The patient reports she is feeling contractions every 2 minutes now and she thinks her water may have broken.

How can the nurse find out if the patients water has broken?

- Check for fluid exiting the vagina, use a Nitrazine test to evaluate if it is amniotic fluid or urine or vaginal discharge

What color should the test be if the membranes have ruptured?

- Blue/purple

The nurse prepares to test the fluid that has leaked down the patients’ leg. The test comes back positive for amniotic fluid. The nurse informs the doctor and prepares the patient to deliver.

What is the most important thing to have ready at this time?

- An infant warmer, if delivery happens the infant needs to be cleaned and placed under the infant warmer while an APGAR test is performed.

The nurse is prepared for the delivery and is talking the mother through her breathing, the cervix is dilated to 7 cm and the contractions are now 1 minute apart.

Vital signs are as follows:

BP 110/67 mmHg

Fetal HR 133 bpm

The nurse checks the presentation of the baby and notes the baby head is in the vertex position, the bottom is in the frank position and baby is in the -1 station.

What station number means the baby is starting to come out?

- Positive numbers indicate the baby is starting to exit the pelvis.

What cardinal movement is the baby currently in?

- Engagement, also called lighting or dropping.

The nurse monitors mom and baby for another hour and upon re-checking the position of the baby the nurse notes that the baby is now +1 station and the cardinal movement is descent and flexion.

What does the nurse need to make sure has happened?

- The doctor has been brought to bedside and staff is ready for delivery

As the baby is delivered the occiput is facing the right side of the pelvis and towards the front.

What position is the newborn in at delivery?

- Right Occiput Anterior (ROA)

View the FULL Outline

When you start a FREE trial you gain access to the full outline as well as:

- SIMCLEX (NCLEX Simulator)

- 6,500+ Practice NCLEX Questions

- 2,000+ HD Videos

- 300+ Nursing Cheatsheets

“Would suggest to all nursing students . . . Guaranteed to ease the stress!”

Nursing Case Studies

This nursing case study course is designed to help nursing students build critical thinking. Each case study was written by experienced nurses with first hand knowledge of the “real-world” disease process. To help you increase your nursing clinical judgement (critical thinking), each unfolding nursing case study includes answers laid out by Blooms Taxonomy to help you see that you are progressing to clinical analysis.We encourage you to read the case study and really through the “critical thinking checks” as this is where the real learning occurs. If you get tripped up by a specific question, no worries, just dig into an associated lesson on the topic and reinforce your understanding. In the end, that is what nursing case studies are all about – growing in your clinical judgement.

Nursing Case Studies Introduction

Cardiac nursing case studies.

- 6 Questions

- 7 Questions

- 5 Questions

- 4 Questions

GI/GU Nursing Case Studies

- 2 Questions

- 8 Questions

Obstetrics Nursing Case Studies

Respiratory nursing case studies.

- 10 Questions

Pediatrics Nursing Case Studies

- 3 Questions

- 12 Questions

Neuro Nursing Case Studies

Mental health nursing case studies.

- 9 Questions

Metabolic/Endocrine Nursing Case Studies

Other nursing case studies.

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 21 June 2018

Normal vaginal delivery at term after expectant management of heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy: a case report

- Olga Vikhareva 1 , 2 ,

- Ekaterina Nedopekina 1 , 2 &

- Andreas Herbst 1 , 2

Journal of Medical Case Reports volume 12 , Article number: 179 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

14k Accesses

8 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Heterotopic pregnancy with a combination of a caesarean scar pregnancy and an intrauterine pregnancy is rare and has potentially life-threatening complications.

Case presentation

We describe the case of a 27-year-old white woman who had experienced an emergency caesarean delivery at 39 weeks for fetal distress with no postpartum complications. This is a report of the successful expectant management of a heterotopic scar pregnancy. The gestational sac implanted into the scar area was non-viable. The woman was treated expectantly and had a normal vaginal delivery at 37 weeks of gestation.

Expectant management under close monitoring can be appropriate in small non-viable heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancies.

Peer Review reports

Heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy (CSP), in which one gestational sac is located in the caesarean scar area and the other one is a normal intrauterine pregnancy, is rare and may have potentially life-threatening complications. The correct management of this condition is unclear. It is a challenge to manage a heterotopic CSP with preservation of the intrauterine pregnancy minimizing the risks for mother and child.

Transvaginal sonography is a valuable diagnostic tool in the management of such pregnancies [ 1 ]. Currently, we offer women with one previous caesarean section participation in an ongoing study of transvaginal ultrasound examinations in each trimester. The study provides support to identify patients with high risk of uterine rupture/potential placental complications to make an individual plan for pregnancy surveillance and delivery.

We have not found previous reports on successful expectant management of spontaneous heterotopic CSP with the preservation of intrauterine pregnancy resulting in a normal vaginal delivery.

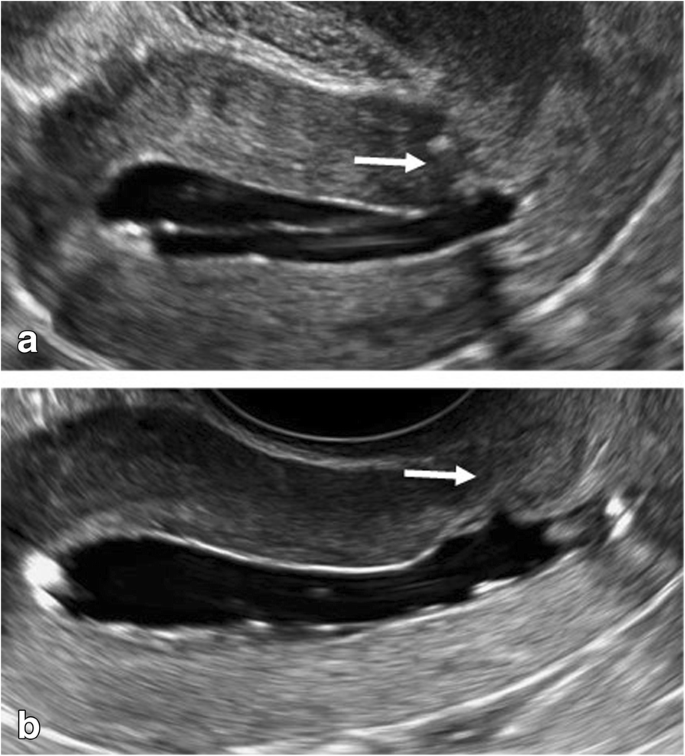

We describe the case of a 27-year-old white woman who had experienced an emergency caesarean delivery at 39 weeks for fetal distress with no postpartum complications. As part of our ongoing study “Vaginal delivery after caesarean section”, she underwent saline contrast sonohysterography 6 months after the caesarean section. The caesarean scar had a small indentation and the remaining myometrium over the defect was 7.5 mm (Fig. 1a ).

Saline contrast sonohysterography images. The arrows indicate the caesarean section scar 6 months after the index caesarean ( a ) and 6 months after the end of the heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy by vaginal delivery ( b ). The thickness of the remaining myometrium appeared almost unchanged

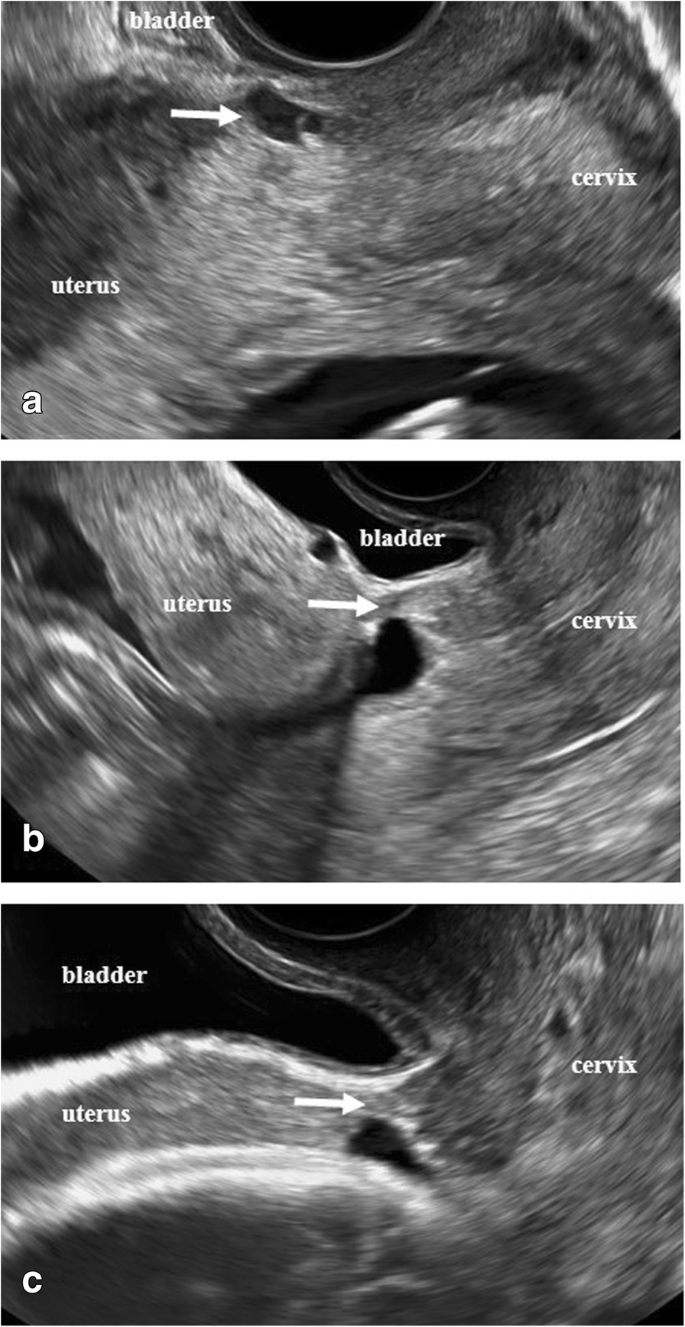

In the current pregnancy, she had a dating scan at around 11 weeks with no remarks. She came for a transvaginal ultrasound examination at around 13 weeks as part of our study. This scan revealed a duplex pregnancy with one viable intrauterine fetus with normal anatomy and placenta located high on the anterior wall and a small gestational sac (8 mm) with a yolk sac without embryo was located in the caesarean scar (Fig. 2a ). There was no extensive vascularity surrounding the sac. One corpus luteum was found in each of the two ovaries. She was asymptomatic.

Transvaginal sonographic images. The arrows indicate the appearance of the cesarean scar area at the presence of the scar pregnancy at 13 + 2 ( a ) and after reabsorption of the scar pregnancy at 22 + 0 ( b ) and at 30 + 2 ( c ) weeks of gestation

She was informed that not enough evidence existed to advise a specific management of this condition. After discussion with her and her husband, expectant management was chosen with a new ultrasound examination after 5 weeks.

She came to our ultrasound department at 18 weeks, 22 weeks, and 30 weeks of gestation. She remained asymptomatic. The ectopic gestational sac was not visualized with transvaginal or transabdominal scans at the 18 weeks examination (Fig. 2b ). The niche in the scar and the thickness of the thinnest part of the remaining myometrium appeared unchanged at all visits. The intrauterine pregnancy developed normally with no signs of abnormal placentation. At 30 weeks of gestation the ultrasound appearance of the scar area did not indicate any contraindications for vaginal delivery. The thickness of the lower uterine segment (LUS) was 4.9 mm (Fig. 2c ). In agreement with our patient, vaginal delivery was planned. The staff of the labor ward was fully informed.

She was admitted to the labor ward with irregular contractions in week 37 + 0. Her cervix dilated to 3 cm with no further progress. Due to that oxytocin augmentation was administered for 3 hours. The duration of active labor was 6.5 hours. A healthy male neonate weighing 2985 g was delivered, with Apgar scores 9–10 at 1 and 5 minutes and umbilical cord pH 7.27. The placenta delivered spontaneously and total blood loss was 250 ml. The postpartum period was without any complications, and she was discharged home the next day.

At a follow-up visit 6 months postpartum, saline contrast sonohysterography showed no signs of the previous CSP, and the remaining myometrium over the hysterotomy scar defect was 5.7 mm (Fig. 1b ).

Ethical approval for the ongoing study was obtained by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of Lund University, Sweden, reference number 2013/176. Our patient has given permission for publication of this case report in a scientific journal.

Discussion and conclusions

Management of heterotopic CSP with an intrauterine gestation is a challenge. Treatment options for CSP include expectant management, and medical or surgical termination [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ].

The use of methotrexate has been reported in management of ectopic gestations, but in heterotopic pregnancies with preservation of intrauterine pregnancy this may cause a teratogenic effect with fetal anomalies [ 5 , 6 ].

A few case reports have described treatment of heterotopic CSP viable pregnancies with local injection of potassium chloride. This method is commonly used for fetal reduction in multiple pregnancy [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. Treatment with potassium chloride is associated with an increased risk of abdominal pain, pregnancy loss, excessive vaginal bleeding, prematurity, need for subsequent surgery, and spontaneous rupture of membranes and subsequent chorioamnionitis [ 1 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ].

Laparoscopic treatment can be an option for removal of an ectopic scar pregnancy, but there is increased risk of hemorrhage and miscarriage [ 7 , 13 , 14 , 15 ].

Michaels et al. suggested that expectant management can be appropriate in early gestations with no heartbeat, often resulting in complete absorption of the trophoblast [ 10 ]. Our patient had no bleeding or abdominal pain. The gestational sac located in the scar was non-viable with no extensive vascularity.

It is difficult to study possible changes in the tissues of the caesarean scar area after reabsorption of CSP. With ultrasound one can appreciate the thickness of LUS during the pregnancy, but not the quality of the myometrium.

Interestingly, it was found that our patient had a small defect in the uterine scar detected at ultrasound 6 months after caesarean section. Jurkovic et al. reported 18 cases of CSP over a 4-year period [ 1 ]. They observed that the majority of scars were well-healed. These data suggest that the size of a defect in the scar does not increase the risk of CSP; however, more studies are needed.

Our patient had a “normal” dating scan at 11 weeks. The early diagnosis of a heterotopic CSP is easy to miss, in particular with presence of an intrauterine viable embryo. Serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is of little value as long as an intrauterine pregnancy is ongoing. Transvaginal ultrasound is the best tool for diagnosis and management of such pregnancies. In our ongoing study “Vaginal delivery after caesarean section” we assess multiple parameters: scar area/scar pregnancy/potential placental complications. These ultrasound characteristics and clinical evaluation together with close monitoring provide support for the obstetrician in management of these women.

The literature is sparse and we still lack evidence and strong clinical guidelines to manage heterotopic pregnancies. Each woman diagnosed with scar implantation should receive an individual approach.

Abbreviations

Caesarean scar pregnancy

Human chorionic gonadotropin

Lower uterine segment

Jurkovic D, Hillaby K, Woelfer B, Lawrence A, Salim R, Elson CJ. First trimester diagnosis and management of pregnancies implanted into the lower uterine segment Cesarean section scar. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;21(3):220–7.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Osborn DA, Williams TR, Craig BM. Cesarean scar pregnancy: sonographic and magnetic resonance imaging findings, complications, and treatment. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:1449–56.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Uysal F, Usal A, Adam G. Cesarean scar pregnancy: diagnosis, management, and follow-up. J Ultrasound Med. 2013;32:1295–300.

Litwicka K, Greco E. Caesarean scar pregnancy: a review of management options. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;23:415–21.

Jordan RL, Wilson JG, Schumacher HJ. Embryotoxicity of the folate antagonist methotrexate in rats and rabbits. Teratology. 1977;15(1):73–9.

Timor-Tritsch IE. Is it safe to use methotrexate for selective injection in heterotopic pregnancy? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:193–4.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A. Unforeseen consequences of the increasing rate of cesarean deliveries: early placenta accreta and cesarean scar pregnancy. A review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(1):14–29.

Mohammed ABF, Farid I, Ahmed B, Ghany EA. Obstetric and neonatal outcome of multifetal pregnancy reduction. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2015;20(3):176–81.

Article Google Scholar

AlShelaly UE, Al-Mousa NH, Kurdi WI. Obstetric outcomes in reduced and non-reduced twin pregnancies. Saudi Med J. 2015;36(9):1122–5.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Michaels AY, Washburn EE, Pocius KD, Benson CB, Doubilet PM, Carusi DA. Outcome of cesarean scar pregnancies diagnosed sonographically in the first trimester. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34(4):595–9.

Salomon LJ, Fernandez H, Chauveaud A, Doumerc S, Frydman R. Successful management of a heterotopic Caesarean scar pregnancy: potassium chloride injection with preservation of the intrauterine gestation: case report. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(1):189–91.

Monteagudo A, Minior VK, Stephenson C, Monda S, Timor-Tritsch IE. Non-surgical management of live ectopic pregnancy with ultrasound-guided local injection: a case series. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;25(3):282–8.

Wang CJ, Chao AS, Yuen LT, Wang CW, Soong YK, Lee CL. Endoscopic management of cesarean scar pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(2):494.e1-4.

Ash A, Smith A, Maxwell D. Caesarean scar pregnancy. BJOG. 2007;114(3):253–63.

Demirel LC, Bodur H, Selam B, Lembet A, Ergin T. Laparoscopic management of heterotopic cesarean scar pregnancy with preservation of intrauterine gestation and delivery at term: case report. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(4):1293.e5-7.

Download references

Availability of data and materials

Data are available in internal digitalized record systems of Skåne University Hospital.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Skåne University Hospital Malmö, Lund University, Box 117, 221 00, Lund, Sweden

Olga Vikhareva, Ekaterina Nedopekina & Andreas Herbst

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Skåne University Hospital, Lund University, Jan Waldenströms gata 47, SE-20502, Malmö, Sweden

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors EN, AH, and OV contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data. The first draft was written by EN and OV and all the authors revised it critically and approved the final version to be published.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Olga Vikhareva .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical approval was obtained by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of Lund University, Sweden, reference number 2013/176.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Vikhareva, O., Nedopekina, E. & Herbst, A. Normal vaginal delivery at term after expectant management of heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy: a case report. J Med Case Reports 12 , 179 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-018-1713-0

Download citation

Received : 13 February 2018

Accepted : 08 May 2018

Published : 21 June 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-018-1713-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy

- Expectant management

- Vaginal delivery

Journal of Medical Case Reports

ISSN: 1752-1947

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Normal Labor and Delivery

Jul 13, 2014

1.49k likes | 2.89k Views

Normal Labor and Delivery. Midwifery Division Department of OB/GYN University of North Carolina School of Medicine. OBJECTIVES. Define labor and its stages Exam of the laboring woman and her fetus Review the cardinal movements of labor and birth Review Disorders of Labor

Share Presentation

- prenatal lab work

- fetal monitoring late decelerations

- midwifery division

- ob gyn university

- internal rotation

- complications

Presentation Transcript

Normal Labor and Delivery Midwifery Division Department of OB/GYN University of North Carolina School of Medicine

OBJECTIVES • Define labor and its stages • Exam of the laboring woman and her fetus • Review the cardinal movements of labor and birth • Review Disorders of Labor • Induction of Labor • Other labor issues

Define Labor and its Stages • Labor: progressive change of the cervix in the setting of uterine contractions • Term Labor: > 37 weeks gestation • Preterm Labor: < 37 weeks gestation • 11% of all US births in 1997 • 80% of preterm births between 34 - 36 weeks • Preterm delivery < 35 weeks: 3.5%

Define Labor and its Stages • Stages of Labor • 1st stage – onset of labor until full cervical dilitation • 2nd stage – from full dilitation to birth of infant • 3rd stage – from birth of infant until delivery of placenta • 4th stage – 2 hours after the delivery of placenta

Define labor and its Stages1st stage and its phases • Latent phase: onset of contractions until active phase • Active phase: 3 cm dilation in nulliparas; 4 cm dilation in multiparas to deceleration phase • Deceleration phase: 8 – 9 cm dilation to complete dilation

Exam of the Laboring woman and her Fetus • Review of prenatal records and labs • Physical exam • 1. Vitals and routine physical exam • 2. Abdominal Exam • Palpation of contractions • Leopold’s maneuvers • 3. Pelvic Exam • 4. Fetal heart rate monitoring

Review of Prenatal Records • Allergies • Medications • Past medical, surgical, obstetrical, gynecologic, social and family histories • Routine prenatal lab work • Complications of current or past pregnancies

Abdominal Exam • 1. Palpation of contractions for duration and intensity • 2. Leopold’s maneuvers • To assess estimated fetal weight, fetal lie, presentation and position, attitude, and (a)synclitism

NORMAL LABOR & DELIVERYEstimated Fetal Weight • Leopold’s maneuvers (palpation of the maternal abdomen) • Ultrasound estimate of fetal weight (error of 10 – 15%) • Maternal estimate of fetal weight (best)

Fetal Lie • Lie: relationship between the long axis of the fetus and the mother • Longitudinal • Transverse • Oblique

Fetal presentation • Presentation: fetal part closet to pelvic inlet • cephalic • breech • shoulder

Fetal position • Position: relationship of fetal presenting part to the maternal pelvis • Occiput • Brow • Mentum • Breech • Shoulder

Fetal Attitude • The relationship of the fetal parts to one another (i.e. flexion extension of head relative to body).

Vertex Parietal Brow Face

(A)synclitism • Synclitism is when the biparietal diameter of the fetal head is parallel to the planes of the maternal pelvis.

Pelvic Exam • Pelvic Exam – sterile vaginal exam +/- sterile speculum exam • Dilation • Effacement • Station • Also position of cervix and consistency important.

Obstetrical Pelvic Exam • Dilation (dilatation): patency of the internal cervical os • 0 = “closed” • 10 cm = “complete” • Effacement: shortening of the cervical length • 0% = “thick” • 100% = “fully effaced”

Obstetrical Pelvic Exam • Station: level of presenting part (bony portion) in relation to the maternal ischial spines • Ischial spines = O station • Above spines: -5 to -1 • Below spines: +1 to +5

Obstetrical Pelvic Exam • Also includes same assessment included in Leopold’s maneuvers (fetal lie, presentation, position, etc.)

Fetal Monitoring • Intermittent • Continuous

Continuous Fetal Monitoring • Baseline rate • Variability • Presence of accelerations • Presence of decelerations • Changes or trends of FHR patterns over time • Contractions

Fetal Heart Rate Baseline • 10 minute window • Duration: at least 2 minutes • Bradycardia: < 110 bpm • Tachycardia: > 170 bpm

Fetal Monitoring (Variability) • Concept of short and long-term variability dropped • Absent: undetectable • Minimal: undetectable - < 5 bpm • Moderate: 6 - 25 bpm • Marked: > 25 bpm

Fetal Monitoring (Accelerations) • Onset to peak: < 30 seconds • > 32 weeks: >15 bpm X >15 secs • < 32 weeks: > 10 bpm X > 10 secs • > 2 minutes in duration: prolonged • > 10 minutes in duration: change in baseline

DECELERATIONSFetal Monitoring (Variables) • Onset to nadir < 30 secs • > 15 bpm below baseline • Duration: > 15 seconds • < 2 minutes from onset to return to baseline

DECELERATIONSFetal Monitoring (Variables) Treatment • Pelvic exam (rule out prolapsed cord) • Maternal oxygen • Change maternal position • Stop pushing • Amnioinfusion

Fetal Monitoring (Early Decelerations) • Onset to nadir > 30 secs • Coincident in timing with UC • Nadir occurring simultaneously with the peak of the contraction

Fetal Monitoring (Late Decelerations) • Onset to nadir > 30 secs • Delayed in timing • Nadir occurring after the peak of the contraction • Reccuring can be ominous

Fetal Monitoring(Late Decelerations) Treatment • Correct hypotension or other maternal conditions • Maternal oxygen • Scalp stimulation • Cesarean delivery if repetitive

Uterine Contractions External tocodynamometry Internal tocodynamometry

What’s going on in there? • The cardinal movements of labor are the mechanism by which the fetus moves progressively through the birth canal.

Cardinal Movements of Labor – Occurring during first and second stages of labor • Engagement: descent of biparietal diameter to the level of the ischial spines (0 station) • Often occurs before onset of labor in nulliparous patients • Descent • Flexion: presenting diameters of fetal head presenting to maternal pelvis are optimized

Cardinal Movements of Labor • Internal rotation: fetal occiput rotates from transverse to AP • Extension: head rotates under symphysis pubis • External rotation (restitution): occiput and spine assume same position • Expulsion: fetal body delivers

- More by User

Normal Labor and Delivery. Midwifery Division Department of OB/GYN University of North Carolina School of Medicine. OBJECTIVES. Describe the maternal factors in birth List the various fetal positions and presentations Review the 7 Cardinal Movements Define the 4 stages of labor

3.05k views • 86 slides

Labor and Delivery

Labor and Delivery. Marcela’s Recipe for Having a Baby: 2 cup Mechanics 2 cups Hormones 3 cup emotional & physical support Mix and Stir with the three stages of labor Time: 8 - 48 hours Makes three: one new mom, one new dad and a brand new baby. Parturition. Birth of the baby

1.13k views • 23 slides

The course and conduct of normal labor and delivery

The course and conduct of normal labor and delivery. Emilia Brzezińska Division of Perinatal Medicine. A definition of labor. Progressive dilatation of the uterine cervix in association with repetitive uterine contractions. Spontaneous or induced Term or preterm. Important terms.

1.56k views • 28 slides

Normal labor and delivery

2. Objectives At the end of session, the student is able to. Diagnose true labor Describe factors influence vaginal birthAssess maternal and fetal conditionAssess progress of laborManage first stage of laborDescribe mechanism of normal vaginal deliveryDescribe steps for conduction vaginal de

1.86k views • 82 slides

Labor and Delivery : Physiology, Normal, Abnormal, and Preterm Labor

Labor and Delivery : Physiology, Normal, Abnormal, and Preterm Labor. William Goodnight, MD, MSCR Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Images: googleimage.com; gabbeobstetrics.com. Objectives. Describe physiology of initiation of labor Define normal and abnormal labor

4.68k views • 55 slides

Labor and Delivery. CAPT Mike Hughey, MC, USNR. Labor. Regular, frequent, leading to progressive cervical effacement and dilatation Braxton-Hicks contractions May be painful and regular, but usually are not Do not lead to cervical change Labor diagnosis usually made in retrospect.

830 views • 30 slides

Ch 13. CONDUCT OF NORMAL LABOR AND DELIVERY

Ch 13. CONDUCT OF NORMAL LABOR AND DELIVERY. 부산백병원 산부인과 R1 서 영 진. The ideal conduct of labor and delivery - Birthing is recognized as a normal physiological process that most women experience without complication

2.42k views • 29 slides

Normal Labor and Delivery 正常分娩

Normal Labor and Delivery 正常分娩. 林建华. Labor : the process by which contractions of uterus expel the fetus. Delivery : receive the neonate. 1. definition. Term pregnancy: 37-42weeks from LMP pre-term delivery (labor): 28- <37 weeks of gestational age post-term delivery: 42 weeks

1.05k views • 24 slides

837 views • 30 slides

Normal Labor and Delivery Physiological Adaptations Chapter 17

Normal Labor and Delivery Physiological Adaptations Chapter 17. Presented by Ann Hearn. LABOR. The process by which the products of conception are expelled from the body. UTERINE CONTRACTIONS.

2.37k views • 53 slides

Normal Labor and Delivery. Valerie Robinson D.O. Contractions Become regular Increase in strength and frequency Cervical change: Dilation and Effacement Normal is >1.2cm/hour in P0, >1.5cm/hour in P>0 0% effacement is 3-4cm thick ROM may be spontaneous or assisted

605 views • 18 slides

Normal Labor and Delivery Physiological Adaptations

Normal Labor and Delivery Physiological Adaptations. Presented by Jeanie Ward. LABOR. The Process by which the Products of Conception are expelled from the body. Passenger. Essential Factors in Labor. Powers. Passageway. Psychological. THE

1.01k views • 37 slides

Normal Labor and Delivery. Nursing Care. Stage 1 -- Latent Phase Signs and Symptoms:. Contraction: dilate 0-3 cm. Mild Duration – 30-45 seconds Frequency – 5-20 minutes Scant pinkish discharge, bloody show Mother’s response Surge of energy and excited Talkative, outgoing Anxiety low

566 views • 32 slides

Normal Labor and Delivery. The Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital of Fudan University Jing-Xin Ding . According to the New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (1993), toil, trouble, suffering, bodily exertion, especially when painful, and an outcome of work are all characteristics of labor .

1.96k views • 121 slides

Labor and Delivery. Stages of Labor. The stages of labor are often thought to be a mystery. In all honesty it is a mystery in many ways. Each woman will have a different labor and yet many parts are the same. . Stages…1-4. Stage 1-Labor ends by being fully dilated.

648 views • 19 slides

Normal Labor and Delivery. The Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital of Fudan University Jing- Xin Ding . Definition.

2.93k views • 157 slides

Normal Labor and Delivery. Nursing Care. Signs and Symptoms of the Stage 1 -- Latent Phase. Contraction: dilate 0-3 cm. Mild Duration – 30-45 seconds Frequency – 5-20 minutes Scant pinkish discharge, bloody show Mother’s response Surge of energy and excited

551 views • 24 slides

Normal Labor and Delivery Physiological Adaptations Chapter 17. Presented by Amie Bedgood. http://youtu.be/IPlqhw8AoQI. LABOR. The process by which the products of conception are expelled from the body. UTERINE CONTRACTIONS.

1.13k views • 54 slides

Normal Labor and Delivery Physiological Adaptations Chapter 17. Presented by Amie Bedgood. LABOR. The process by which the products of conception are expelled from the body. UTERINE CONTRACTIONS.

948 views • 53 slides

Normal labor and delivery. Definition of labor Causes of onset of labor Changes before labor (premonitory symptoms) True labor Essential factors of labor Stages of labor Clinical course and management of stages. Definition (1).

2.55k views • 130 slides

Normal Labor or Delivery

Normal Labor or Delivery. Chen Danqing Women’s hospital,School of medicine, Zhejiang University. Objective. Definition of labor. Determinate Factors of Labor Anatomical considerations: The female pelvis. The fetal skull. The stages of labor. The mechanism of labor (vertex, LOA).

1.05k views • 67 slides

Normal Labor and Delivery. Asja Ćosić Mentor: A. Žmegač Horvat. Labor. labor series of rhythmic, progressive contractions of the uterus gradually move the fetus through the cervix and birth canal main stages of labor

667 views • 12 slides

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Case Rep Womens Health

- v.33; 2022 Jan

A case report of successful vaginal delivery in a patient with severe uterine prolapse and a review of the healing process of a cervical incision

Associated data.

The incidence of severe uterine prolapse during childbirth is approximately 0.01%. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, no reports detail the healing process of the cervix during uterine involution. This report describes successful vaginal delivery and the healing process of postpartum uterine prolapse and cervical tears in a patient with severe uterine prolapse.

Case presentation

A patient in her 40s (gravida 3, para 1, abortus 1) with severe uterine prolapse successfully delivered a live female baby weighing 3190 g at 38 + 5 weeks of gestation by assisted vaginal delivery. Uterine prolapse had improved to approximately 2° by 2 months postoperatively. On postpartum day 4, during the healing process of cervical laceration, the thread loosened in a single layer of continuous sutures due to uterine involution, and poor wound healing was observed. The wound was subsequently re-sutured with a two-layer single ligation suture (Gambee suture + vertical mattress suture). However, on postpartum day 11, a large thread ball was hindering the healing of the muscle layer, which improved with re-suturing.

Although vaginal delivery in a patient with severe uterine prolapse is possible in some cases, the cervix should be sutured, while considering cervical involution after delivery.

- • Pregnancies with complete uterine prolapse are exceedingly rare.

- • When suturing the uterus, involution after delivery should be considered.

- • This is the first report on the healing process of cervical canal lacerations.

1. Introduction

Pregnancies complicated by uterine prolapse are rare, and cases of severe uterine prolapse are rarer [ 1 ]. Recommendations regarding the management of this infrequent but potentially fatal condition are scarce [ 1 ]. Pregnancies with severe uterine and cervical prolapse have been reported; however, the delivery method is complicated in most cases, and few reports of successful vaginal delivery despite severe cervical edema have been reported in the literature [ 2 ]. This report describes a case of vaginal delivery in a patient with severe uterine prolapse and presents the first description of the healing process after a Duhrssen incision performed on a prolapsed cervix.

2. Case Presentation

A 43-year-old woman, gravida 3, para 1, abortus 1, implanted with frozen-thawed embryos was diagnosed with high-risk pregnancy at her previous hospital. Her obstetric history included a term, vaginal singleton delivery (3298 g, male neonate) 4 years earlier, which was complicated by a retained placenta. The placenta was removed manually. Thereafter, no uterine prolapse was observed.

She had been undergoing treatment for hypertension and dermatomyositis since 2018. She had been prescribed nifedipine CR 20 mg/day for the hypertension and steroids (prednisolone) 4.0 mg/day and tacrolimus 3.4 mg/day for the dermatomyositis. As the symptoms of dermatomyositis improved in 2019, the pregnancy was approved. She had also undergone sub-plasmalemmal myomectomy 10 years previously. She was otherwise fit and had a normal body mass index; she did not smoke and had no allergies. During the index pregnancy, at the 19-week check-up, her cervix was found to have descended. Subsequent regular ultrasound scans at 24, 26, 30, 32, and 34 weeks of gestation demonstrated normal fetal morphology, with normal and concordant fetal growth. An ultrasound scan at 36 weeks showed that the cervical canal was very long (8.8 cm) and closed ( Fig. 1 ). A 95-mm self-removable donut-shaped pessary (donut support for 3° prolapse/procidentia; CooperSurgical Milex™, 75 Corporate Drive Trumbull, CT 06611 USA) appeared to drop out spontaneously. Color Doppler imaging with 3D transvaginal ultrasonography revealed cervical edema ( Fig. 2 ). Color Doppler examination did not reveal any obvious blood flow. She was admitted to hospital at 37 + 2 weeks due to a worsening skin rash over the perineum and difficulty in washing. Her blood pressure was stable, her general condition was good, and there were no abnormal clinical or biochemical findings suggestive of an infection.

Photographs at the onset of uterine prolapse at 36 weeks of gestation.

Cervical edema and cervical length of 8.8 cm, color Doppler with 3D transvaginal ultrasonography.

A, Sagittal section; B, Coronal section; C, Transverse section; D, Color Doppler.

In the pre-induction state of the cervix, the Bishop scoring system showed that the cervical os was dilated by 4 cm, effaced 0%, station −3, soft, and anterior 7 points. Induction with oxytocin was commenced at 38 weeks and 4 days of gestation for planned delivery, but there were no effective contractions. The next day, the cervix was dilated by 6 cm and effaced 30%.

With the patient's consent, we performed an artificial rupture of the membranes, which led to labor progression. After an intramuscular injection of butyl scopolamine, her cervix was softened for a short time. The cervix was completely prolapsed outside the vagina, but the station had reached +1 in relation to the pubic symphysis. The 95-mm donut-type pessary was easily removed from the soft birth canal, and vacuum extraction delivery (Kiwi®) was deemed feasible. Cervix-holding forceps were used, and a Duhrssen incision was made under visualization as labor progressed. A cervical Duhrssen incision of approximately 5 cm was made, and the length of the incision was extended to 10 cm. We did not perform a perineal incision. After three traction cycles, a live female neonate weighing 3190 g was delivered, with Apgar scores of 8/9 (1st and 5th minutes) and a pH of 7.319. The delivery was complicated with a retained placenta and massive postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), with blood loss of 2500 mL. The cervix was sutured, as usual, using 0 Vicryl® sutures in one continuous layer from 5 mm above the upper edge of incision, and the surface of the suture appeared to be fine. However, on discharge examination on the 4th day post-delivery, a complete breakdown of the repair of approximately 5 cm of the cervical canal was identified at the introitus. After she was returned to the operating theatre, debridement was performed; the first layer was sutured with a single ligation using the Gambee suture (2–0 Vicryl®), and the second layer was sutured with an end-to-end single ligation using the mattress suture technique (2–0 Vicryl®). On the 7th day after re-suturing (11th day after delivery), the uterus was markedly involuted, and uterine prolapse somewhat improved, but the ligature threads were collected in one place and became a single ball of threads. All sutures were removed, and the wound was re-sutured with two Z-sutures using a 3–0 Vicryl® thread. Sutures were removed 1 month postpartum, and complete wound healing was confirmed. Two months post-surgery, uterine prolapse had improved to a 2° prolapse. The healing process of cervical laceration and cervical canal prolapse is shown in Fig. 3 .

Healing process of cervical laceration and cervical canal prolapse.

A: Cervical laceration suture surface on the day of delivery.

B: On postpartum day 4, suture failure was noted due to a continuous 1-layer suture (0 mesh thread (Vicryl®), absorbable thread).

C: On postpartum day 4, stitches were removed and debridement was performed.

D: On postpartum day 4, re-suture and first-layer Gambee suture (2–0 mesh thread, absorbable (Vicryl®)) were performed.

E: On postpartum day 4, re-suture and second-layer horizontal mattress suture (2–0 mesh thread, absorbable (Vicryl®)) were performed.

F: On postpartum day 11, the thread had formed into a ball, which interfered with viability. The wound was re-sutured using a single ligation due to suture failure (3–0 mesh thread, absorbable (Vicryl®)).

G: On postpartum day 28, uterine prolapse improved to 2°–3°, and the wound became viable.

3. Discussion

Uterine and cervical prolapse are rare in pregnancy. Uterine prolapse during pregnancy is a precarious event, with an incidence of 1 in 10,000–15,000 pregnancies [ 3 ]. It can be associated with minor cervical desiccation and ulceration or devastating maternal fatalities. Complications include urinary retention, preterm labor, premature delivery, fetal demise, maternal sepsis, and urinary retention [ 1 ].

Prolapse development in pregnancy is likely due to an escalation of the physiological changes in pregnancy, leading to a weakening of pelvic organ support [ 4 ]. Increased cortisol and progesterone levels during pregnancy may contribute to uterine relaxation. In our case, the patient did not have any congenital risk factors. However, she had developed dermatomyositis after her last delivery and had been prescribed prednisolone 4 mg/day which she had taken consistently since before pregnancy. In a previously reported case study, pessary insertion resulted in the temporary improvement of uterine prolapse [ 5 , 6 ], but, in our case, a 95-mm donut pessary (CooperSurgical Milex™) easily slipped out of the soft birth canal. According to a case review of pregnancies with uterine prolapse reported by Kana et al. [ 7 ], since 1997, vaginal delivery could be performed in only 2 of 16 patients with cervical edema, and none of them was diagnosed with complete uterine prolapse. Jeong et al. [ 8 ] reported that, since 2002, only 1 of 14 patients with uterine prolapse was able to be delivered vaginally. These results suggest that this study reports a valuable case of vaginal delivery. In fact, the two cases reported recently were both delivered by cesarean section [ 9 , 10 ].

We performed vaginal delivery, and a Duhrssen incision was stitched with minimal blood loss. In active labor, a prolapsed cervix that is enlarged and edematous can be managed with a topical concentrated magnesium solution to treat cervical dystocia and lacerations [ 11 ]. Verma et al. reported that two incisions approximately 3 cm long each were made at 2 o'clock and 10 o'clock positions on the cervix using tissue-cutting scissors [ 12 ]. In contrast, our approach involves using one incision that is approximately 5 cm long at the 6 o'clock position on the cervix using tissue-cutting scissors. Cervical laceration suturing was performed, and we observed that a single layer of continuous sutures had lost tension and was loose due to the significant involution of the cervix. Moreover, the external os was found outside the vagina; thus, the wound could not be covered, and thread traction could not prevent incision separation at 6 o'clock. After debridement, Gambee sutures and horizontal mattress sutures were used to re-suture the wound, but on postpartum examination on day 11, the ligature thread from the single ligation suture had formed a ball of threads. We re-sutured the wound using 3–0 Vicryl® sutures, and the wound was stabilized. The cervix was edematous and markedly dilated; therefore, any sutures are likely to be extruded as the cervix involutes and the edema improves. A technique that results in the end-to-end apposition of the incision is more likely to succeed as it allows for clot formation and healing by primary intention with less reliance on suture tension. Nevertheless, the majority of such cases have been managed by cesarean section. This vaginal delivery resulted in a prolonged process of labor induction, cervical incision (which likely induced long-term cervical incompetence), three trips to the operating room, a retained placenta, and a massive PPH; however, direct causality of the last two factors is unknown. Avoiding cesarean section in this case resulted in an unavoidable burden on the patient after delivery. Although we do not necessarily recommend vaginal delivery, we report it as an option. An extensive literature search listing the keywords “healing process, cervical canal lacerations, single ligation suture, and continuous sutures” revealed that this is the first report on the healing process of cervical canal lacerations.

4. Conclusion

Vaginal delivery of a pregnancy complicated by severe uterine prolapse is possible in some cases. Given the paucity of data on the management and pregnancy outcomes of patients with uterine anomalies, such cases should be considered high risk, and individualized care should be given to patients to optimize outcomes. Moreover, when suturing the uterus cervix, uterus cervical involution after delivery should be considered. This case report adds to the literature as it highlights the management of a rare obstetric condition.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

Video of assisted vaginal delivery and salvage from cervical dystocia in uterocervical prolapse: Duhrssen incision

Supplementary material

Contributors

Jota Maki was responsible for the conceptualization of the case report, was the main author, conducted the literature review, and drafted the manuscript, and was involved in the patient’s treatment, from outpatient care to hospitalization and discharge.

Tomohiro Mitoma was responsible for the conceptualization of the case report, was involved in the case, and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Sakurako Mishima was responsible for the conceptualization of the case report, and reviewed the draft.

Akiko Ohira was responsible for the conceptualization of the case report, and reviewed the draft.

Kazumasa Tani was responsible for the conceptualization of the case report, and reviewed the draft.

Eriko Eto was responsible for the conceptualization of the case report, was involved in the case, and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Kei Hayata was responsible for the conceptualization of the case report, and reviewed the draft.

Hisashi Masuyama was responsible for the conceptualization of the case report, was involved in the case, and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

All authors approved the final version of the paper and take full responsibility for the work.

This work did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Patient consent

The patient provided informed consent for the publication of this report and all accompanying images.

Provenance and peer review

This case report was not commissioned and was peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements

We thank the obstetrics surgeons and other healthcare personnel involved in the treatment of patients at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Okayama University Hospital.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this case report.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to present patient...

How to present patient cases

- Related content

- Peer review

- Mary Ni Lochlainn , foundation year 2 doctor 1 ,

- Ibrahim Balogun , healthcare of older people/stroke medicine consultant 1

- 1 East Kent Foundation Trust, UK

A guide on how to structure a case presentation

This article contains...

-History of presenting problem

-Medical and surgical history

-Drugs, including allergies to drugs

-Family history

-Social history

-Review of systems

-Findings on examination, including vital signs and observations

-Differential diagnosis/impression

-Investigations

-Management

Presenting patient cases is a key part of everyday clinical practice. A well delivered presentation has the potential to facilitate patient care and improve efficiency on ward rounds, as well as a means of teaching and assessing clinical competence. 1